Histopathologic diagnosis of dermatitis

Histopathology of dermatitis can be performed in uncertain cases of inflammatory skin condition that remain uncertain after history and physical examination.[1]

Sampling

Generally a skin biopsy:

- For punch biopsies, a size of 4 mm is preferred for most inflammatory dermatoses.[2]

- Panniculitis or cutaneous lymphoproliferative disorders: 6 mm punch biopsy or skin excision.[2]

A superficial or shave biopsy is regarded as insufficient.[2]

Fixation

Staining

Generally 3 sections for H&E staining and one section with periodic acid Schiff (PAS)[notes 1][2]

- If suspected bacterial and fungal microorganisms, consider Gram stain and Gomori methenamine silver stain.[2]

Microscopic evaluation

One approach is to classify into mainly either of the following, primarily based on depth of involvement:[2]

- Epidermis, papillary dermis, and superficial vascular plexus:

- Vesiculobullous lesions

- Pustular dermatosis

- Non vesicullobullous, non-pustular

- With epidermal changes

- Without epidermal changes. These characteristically have a superficial perivascular inflammatory infiltrate, and can be classified by type of cell infiltrate:[2]

- Lymphocytic (most common)

- Lymphoeosinophilic

- Lymphoplasmacytic

- Mast cell

- Lymphohistiocytic

- Neutrophilic

Continue in corresponding section:

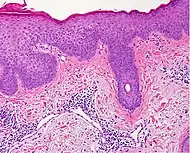

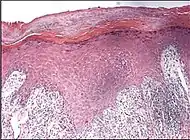

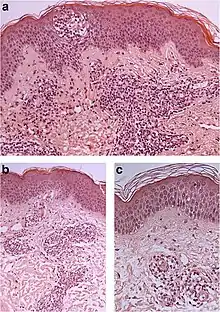

Spongiotic dermatitis

It is characterized by epithelial intercellular edema.[2]

| Characteristics | Micrograph | Photograph | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute | Subacute | Chronic | |||

| Generally/Not otherwise specified[notes 2] | Typical findings:[2]

|

Typical findings:[2]

|

Typical findings:[2]

PAS stain is essential to exclude fungal infection.[2] |

Subacute Subacute |

|

| Allergic/contact dermatitis or atopic dermatitis | As above. Eosinophils may be present in the dermis and epidermis (eosinophilic spongiosis).[2] |  Allergic dermatitis Allergic dermatitis |

.jpg.webp) Atopic dermatitis Atopic dermatitis | ||

| Seborrheic dermatitis | Typical findings:[5]

|

Typical findings:[5]

|

Typical findings:[5]

|

| |

In addition to above, an unspecific spongiotic dermatitis can be consistent with nummular dermatitis, dyshidrotic dermatitis, Id reaction, dermatophytosis, miliaria, Gianotti-Crosti syndrome and pityriasis rosea.[2][notes 2]

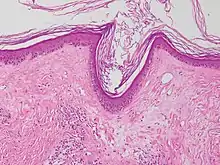

Interface dermatitis

These are sorted into either:[2]

- Interface dermatitis with vacuolar change

- Interface dermatitis with lichenoid inflammation

Interface dermatitis with vacuolar change

| Main conditions[6] | Characteristics | Micrograph | Photograph | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Generally/Not otherwise specified | Typical findings, called "vacuolar interface dermatitis":[6]

|

|

||

| Acute graft-versus-host-disease |  |

|||

| Allergic drug reaction |  |

|||

| Lichen sclerosus | Hyperkeratosis, atrophic epidermis, sclerosis of dermis and dermal lymphocytes.[7] |  | ||

| Erythema multiforme | ||||

| Lupus erythematosis | Typical findings in systemic lupus erythematosus:[8]

|

|

|

An interface dermatitis with vacuolar alteration, not otherwise specified, may be caused by viral exanthems, phototoxic dermatitis, acute radiation dermatitis, erythema dyschromicum perstans, lupus erythematosus and dermatomyositis.[2]

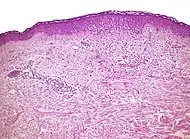

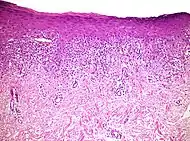

Interface dermatitis with lichenoid inflammation

| Main conditions[2] | Characteristics | Micrograph | Photograph |

|---|---|---|---|

| Generally/Not otherwise specified | Typical findings:[2]

|

||

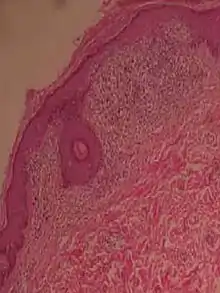

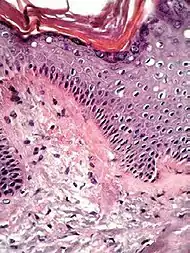

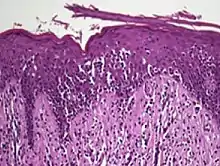

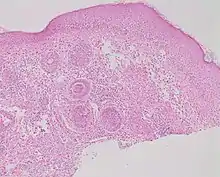

| Lichen planus | Irregular epidermal hyperplasia with a jagged “sawtooth” appearance, compact hyperkeratosis or orthokeratosis, foci of wedge-shaped hypergranulosis, basilar vacuolar degeneration, slight spongiosis in the spinous layer, and squamatization. The dermal papillae between the elongated rete ridges are frequently dome shaped. Necrotic keratinocytes can be observed in the basal layer of the epidermis and at the dermal-epidermal junction. Eosinophilic remnants of anucleate apoptotic basal cells may also be found in the dermis and are referred to as “colloid or civatte bodies”. Whickham striae are usually seen in the areas of hypergranulosis. Vacuolar degeneration at the basal layer may be noted leading to focal subepidermal clefts (Max Joseph spaces). Squamatization occurs as a result of maturation and flattening of cells in the basal layer. It happens in areas of marked hypergranulosis with prominence of the sawtooth pattern of rete ridges. Wedge-shaped hypergranulosis can occur in the eccrine ducts (acrosyringia) or hair follicles (acrotrichia). In the hypertrophic subtype, the associated hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, hypergranulosis, papillomatosis, acanthosis, and hyperplasia markedly increased with thicker collagen bundles forming in the dermis. Moreover, the rete ridges are more elongated and rounded as opposed to the typical sawtooth pattern. In atrophic LP, loss of the rete ridges and dermal fibrosis is prominent. In vesiculobullous LP, the disease progression is quicker. Hence, some of the distinctive features such as hyperkeratosis, hypergranulosis, or dense lymphocytic dermal-epidermal infiltrate may not be present. LP lesion may resolve with residual hyperpigmentation caused by a persistent increase in the number of melanophages in the papillary dermis.[9] |  |  |

| Lichenoid drug reaction |

Can virtually be indistinguishable from cutaneous LP both clinically and histopathologically.

|

| |

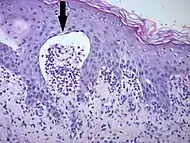

| Lichen nitidus |

|

|  |

| Lichen amyloidosus | Presence of amyloid, possibly with direct immunofluorescence and Congo red staining.[11] |  Congo red. |

Interface dermatitis with lichenoid inflammation, not otherwise specified, can be caused by lichen planus-like keratosis, lichenoid actinic keratosis, lichenoid lupus erythematosus, lichenoid GVHD (chronic GVHD), pigmented purpuric dermatosis, pityriasis rosea, and pityriasis lichenoides chronica.[2] Unusual conditions that can be associated with a lichenoid inflammatory cell infiltrate are HIV dermatitis, syphilis, mycosis fungoides, urticaria pigmentosa, and post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation.[2] In cases of post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation, it is important to exclude potentially harmful mimics such as a regressed melanocytic lesion or lichenoid pigmented actinic keratosis.[2]

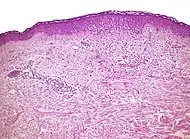

Psoriaform dermatitis

Examining multiple deeper levels is recommended if initial cuts do not correlate well with the clinical history.[2]

Psoriaform dermatitis typically displays:[2]

- Regular epidermal hyperplasia, elongation of the rete ridges, hyperkeratosis, and parakeratosis.

- Usually:A superficial perivascular inflammatory infiltrate

- Often: Thinning of epidermal cells overlying the tips of dermal papillae (suprapapillary plates), and dilated, tortuous blood vessels within these papillae

Further histopathologic diagnosis is performed by the following parameters:

| Condition | Hyperkeratosis | Parakeratosis | Acanthosis | Suprapapillary plate | Granular cell layer changes | Spinous cell layer changes | Basal cell layer changes | Other distinctive feature | Micrograph | Photograph |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psoriasis | Present | Diffuse | Regular | Thin | Decreased or absent | Increased mitoses; minimal spongiosis Clubbed rete pegs[12][13] | Absent |

|

| |

| Psoriasiform drug reaction | Present | Focal | Regular and irregular | Normal or thick | Normal | Spongiosis; eosinophilic infiltrate | Inflammatory cells; Civatte bodies | |||

| Chronic allergic/contact and atopic dermatitis | Present | Focal; crust may be present | Irregular | Normal or thick | Normal | Spongiosis; eosinophilic infiltrate | Absent | |||

| Fungal infection | Compact | Focal; crust may be present | Irregular | Normal or thick | Normal | Occasional neutrophiles; | Absent | |||

| Lichen simplex chronicus | Present | Focal; thick crust | Regular or irregular | Thin or thick | Thickened; hypergranulosis | ±minimal inflammatory infiltrate | Absent | |||

| Scabies | Present | Focal or diffuse | Irregular | Normal or thick | Normal | Inflammatory infiltrate; eosinophilic spongiosis | Absent | |||

| Seborrheic dermatitis and HIV dermatitis | Present | Focal | Irregular | Normal or thick | Normal | Spongiosis; lymphocytic and neutrophilic infiltrate | Absent | |||

| Pityriasis rubra pilaris | Compact | Shoulder parakeratosis;[notes 3] alternating orthokeratosis and parakeratosis | Regular or irregular | Normal or thick | Normal | Spongiosis; lymphocytic infiltrate; rare acantholysis | Occasional vacuolar change | |||

| Pityriasis rosea | Present | Focal | Irregular | Normal or thick | Normal | Small foci of spongiosis; lymphocytic infiltrate | Occasional necrotic keratinocytes | |||

| Syphilis | Present | Focal | Regular or irregular | Normal or thick | Normal | Lymphocytes and neutrophils | Interface change | |||

| Pityriasis lichenoides chronica | Present | Caps of parakeratosis | Irregular | Normal | Normal | Mild spongiosis, lymphocytic infiltrate; necrotic keratinocytes | Necrotic keratinocytes | |||

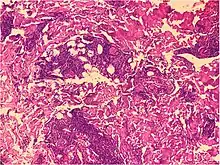

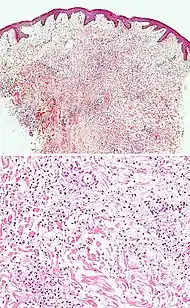

| Mycosis fungoides | Present | Focal | Regular or irregular | Normal | Normal | Minimal or no spongiosis; ±Pautrier microabscess | Atypical lymphoid cells lining the dermo–epidermal junction |  Pautrier microabscesses |

Lymphocytic infiltrate

| Main conditions[2] | Characteristics | Micrograph | Photograph |

|---|---|---|---|

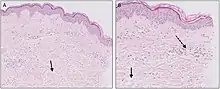

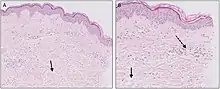

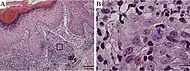

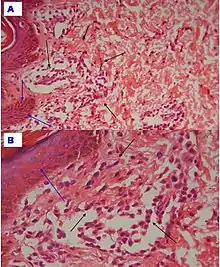

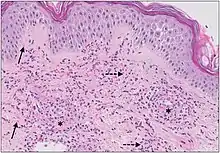

| Urticaria, lymphocyte predominant | Perivascular location. Mast cells are relatively sparse, potentially demonstrated with special stains, preferably tryptase stain. Extravasated erythrocytes are present in about 50% of the cases. No vasculitis.[14] |  Dermal edema [solid arrows in (A,B)] and a sparse superficial predominantly perivascular and interstitial infiltrate of lymphocytes and eosinophils without signs of vasculitis (dashed arrow).[15] Dermal edema [solid arrows in (A,B)] and a sparse superficial predominantly perivascular and interstitial infiltrate of lymphocytes and eosinophils without signs of vasculitis (dashed arrow).[15] |

|

| Fungal skin infection | Often visible fungus. Other signs depend on fungus species.[16] | ||

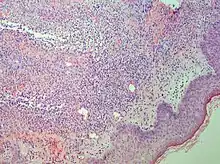

| Pigmented purpuric dermatosis |

|

|

|

| Erythema annulare centrifugum |

Deep lesions: Sharply demarcated perivascular mononuclear cell infiltrate in middle to deep dermis[18] |

|

|

| Not otherwise specified[notes 2] | A lesion with superficial lymphocytic infiltrate without additional histopathologic characteristics can be due to for example drug reactions and insect bites.[2][notes 2] |

Lymphoeosinophilic infiltrate

| Main conditions[2] | Characteristics | Micrograph | Photograph |

|---|---|---|---|

| Urticaria, lymphocyte predominant | Perivascular location. Mast cells are relatively sparse, potentially demonstrated with special stains, preferably tryptase stain. Extravasated erythrocytes are present in about 50% of the cases. No vasculitis.[14] |  Dermal edema (solid arrows) and a sparse superficial predominantly perivascular and interstitial infiltrate of lymphocytes and eosinophils (dashed arrow) Dermal edema (solid arrows) and a sparse superficial predominantly perivascular and interstitial infiltrate of lymphocytes and eosinophils (dashed arrow) |

|

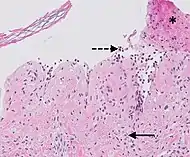

| Prevesicular stage of bullous pemphigoid | Image at right shows influx of inflammatory cells including eosinophils and neutrophils in the dermis (solid arrow) and blister cavity (dashed arrows), and deposition of fibrin (asterisks).[15] However, the diagnosis of bullous pemphigoid consist of at least 2 positive results out of 3 criteria:[19]

|

|

|

| Not otherwise specified[notes 2] | A lesion with superficial lymphoeosinophilic infiltrate without additional histopathologic characteristics can be due to for example drug reactions and insect bites.[2][notes 2] |

Lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate

| Main conditions[2] | Characteristics | Micrograph | Photograph |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rosacea | Typically enlarged, dilated capillaries and venules located in the upper dermis, angulated telangiectasias, perivascular and perifollicular lymphocytic infiltration, and superficial dermal edema.[20] |  |

|

| Secondary syphilis | Various, but often one or a combination of:[21]

|

|

_on_the_soles_of_the_feet._Plantar_lesions-CDC.jpg.webp) |

| Erythema migrans | Typically a superficial and deep perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate.[22] Plasma cells are typically located at the periphery of the lesion, whereas eosinophils are in the center.[22] |  | |

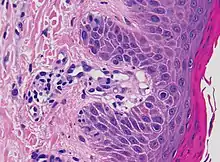

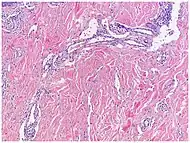

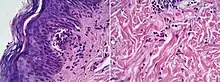

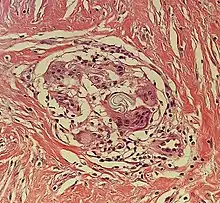

| Kaposi’s sarcoma in patch stage | The patch stage typically shows irregular proliferation of jagged vascular channels in the dermis below an integral epidermis. The so-called promontory sign is sometimes found in patch stage lesions and denotes vascular spaces surrounding pre-existing blood (see image).[23]

vessels |

|

|

| Not otherwise specified[notes 2] | A lesion with superficial lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate without additional histopathologic characteristics can be due to for example trauma, ulceration, scar and early cutaneous connective tissue diseases.[2][notes 2] |

Mastocytosis

| Main conditions[2] | Characteristics | Micrograph | Photograph |

|---|---|---|---|

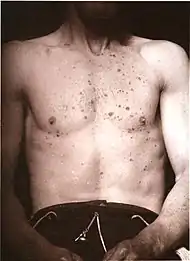

| Urticaria pigmentosa | Mastocytosis with a clinical picture of darkish spots. |  |

|

| Not otherwise specified[notes 2] | Includes the rare disease of primary mastocytosis.[2][notes 2] |

Lymphohistiocytic infiltrate

These include bacterial infections including leprosy, and the sample should therefore be stained with Ziel-Neelsen, acid fast stains, Gomori methenamine silver, PAS, and Fite stains.[2] If negative, an unspecific lymphohistocytic dermatosis may be caused by drug reactions and viral infections.[2][notes 2]

Neutrophilic infiltrate

| Main conditions[2] | Characteristics | Micrograph | Photograph |

|---|---|---|---|

| Urticaria, neutrophil predominant |  |

| |

| Dermatitis herpetiformis |

|

|

|

| Early linear IgA bullous dermatosis | Subepidermal blister formation.[26] |  |

|

| Early febrile neutrophilic dermatosis (Sweet's syndrome) | Neutrophilic and lymphohistiocytic infiltrate and edema.[27] |  |

|

| Connective tissue disorders |

|

|

|

| Cutaneous small-vessel vasculitis |

|

|

|

Multinucleated giant cells

- Foreign bodies indicate a foreign body granuloma.

- Specific forms of multinucleated giant cells include the Touton giant cell, which contains a ring of nuclei surrounding a central homogeneous cytoplasm, with foamy cytoplasm surrounding the nuclei.[29][30] The central cytoplasm (surrounded by the nuclei) may be both amphophilic and eosinophilic.[31]

.jpg.webp) Touton giant cell

Touton giant cell

Notes

- PAS is for evaluation of the epidermal basement membrane, blood vessels, and the presence of fungal organisms

- In "not otherwise specified" cases, a diagnosis may be reached by a review of the medical history and physical examination, based upon the potential conditions at hand.

- Parakeratotic mounds at the edge of follicular ostia.

- Pigmented purpuric dermatitis of Gougerot and Blum particularly have a tendency for lichenoid infiltrate.

References

- "Eczema". University of Maryland Medical Center. Archived from the original on 27 July 2016.

- Alsaad, K O (2005). "My approach to superficial inflammatory dermatoses". Journal of Clinical Pathology. 58 (12): 1233–1241. doi:10.1136/jcp.2005.027151. ISSN 0021-9746. PMC 1770784. PMID 16311340.

- Katarzyna Lundmark, Krynitz, Ismini Vassilaki, Lena Mölne, Annika Ternesten Bratel. "Handläggning av hudprover – provtagningsanvisningar, utskärningsprinciper och snittning (Handling of skin samples - Instructions for sampling, cutting and incision" (PDF). KVAST (Swedish Society of Pathology). Retrieved 2019-09-09.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Page 678 in: Chhabra, Seema; Minz, RanjanaWalker; Saikia, Biman (2012). "Immunofluorescence in dermatology". Indian Journal of Dermatology, Venereology and Leprology. 78 (6): 677–691. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.102355. ISSN 0378-6323. PMID 23075636. S2CID 1331564.

- Mowafak Hamodat. "Skin inflammatory (nontumor) > Spongiotic, psoriasiform and pustular reaction patterns > Seborrheic dermatitis". PathologyOutlines.com. Topic Completed: 1 August 2011. Revised: 26 March 2019

- Unless else specified in boxes, reference is: Alsaad, K O (2005). "My approach to superficial inflammatory dermatoses". Journal of Clinical Pathology. 58 (12): 1233–1241. doi:10.1136/jcp.2005.027151. ISSN 0021-9746.

- Lisa K Pappas-Taffer. "Lichen Sclerosus". Medscape. Updated: May 17, 2018

- Mowafak Hamodat. "Skin inflammatory (nontumor) > Lichenoid and interface reaction patterns > Lupus: systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)". PathologyOutlines. Topic Completed: 1 August 2011. Revised: 26 March 2019

- Gorouhi, Farzam; Davari, Parastoo; Fazel, Nasim (2014). "Cutaneous and Mucosal Lichen Planus: A Comprehensive Review of Clinical Subtypes, Risk Factors, Diagnosis, and Prognosis". The Scientific World Journal. 2014: 1–22. doi:10.1155/2014/742826. ISSN 2356-6140. PMC 3929580. PMID 24672362.

- Attribution 3.0 Unported (CC BY 3.0) - Al-Mutairi N, Hassanein A, Nour-Eldin O, Arun J (2005). "Generalized lichen nitidus". Pediatr Dermatol. 22 (2): 158–60. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2005.22215.x. PMID 15804308. S2CID 6281902.

- Shenoi, SD; Balachandran, C; Mehta, VandanaRai; Salim, T (2005). "Lichen amyloidosus: A study of clinical, histopathologic and immunofluorescence findings in 30 cases". Indian Journal of Dermatology, Venereology and Leprology. 71 (3): 166–169. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.16230. ISSN 0378-6323. PMID 16394404.

- Kunz M, Ibrahim SM (2009). "Cytokines and cytokine profiles in human autoimmune diseases and animal models of autoimmunity". Mediators of Inflammation. 2009: 1–20. doi:10.1155/2009/979258. PMC 2768824. PMID 19884985.

- Raychaudhuri SK, Maverakis E, Raychaudhuri SP (January 2014). "Diagnosis and classification of psoriasis". Autoimmunity Reviews. 13 (4–5): 490–5. doi:10.1016/j.autrev.2014.01.008. PMID 24434359.

- Barzilai, Aviv; Sagi, Lior; Baum, Sharon; Trau, Henri; Schvimer, Michael; Barshack, Iris; Solomon, Michal (2017). "The Histopathology of Urticaria Revisited—Clinical Pathological Study". The American Journal of Dermatopathology. 39 (10): 753–759. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000000786. ISSN 0193-1091. PMID 28858880. S2CID 45809524.

- Giang, Jenny; Seelen, Marc A. J.; van Doorn, Martijn B. A.; Rissmann, Robert; Prens, Errol P.; Damman, Jeffrey (2018). "Complement Activation in Inflammatory Skin Diseases". Frontiers in Immunology. 9: 639. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2018.00639. ISSN 1664-3224. PMC 5911619. PMID 29713318.

- Guarner, J.; Brandt, M. E. (2011). "Histopathologic Diagnosis of Fungal Infections in the 21st Century". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 24 (2): 247–280. doi:10.1128/CMR.00053-10. ISSN 0893-8512. PMC 3122495. PMID 21482725.

- Stephen Lyle. "Pigmented purpuric dermatoses". Dermpedia.org. Retrieved 2019-11-05.

- "Histology of erythema annulare centrifugum". DermNet NZ. Retrieved 2019-11-05.

- Meijer JM, Diercks GF, de Lang EW, Pas HH, Jonkman MF (December 2018). "Assessment of diagnostic strategy for early recognition of bullous and nonbullous variants of pemphigoid". JAMA Dermatol. 155 (2): 158–165. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.4390. PMC 6439538. PMID 30624575.

- Celiker, Hande; Toker, Ebru; Ergun, Tulin; Cinel, Leyla (2017). "An unusual presentation of ocular rosacea". Arquivos Brasileiros de Oftalmologia. 80 (6): 396–398. doi:10.5935/0004-2749.20170097. ISSN 0004-2749. PMID 29267579.

- Assoc Prof Patrick Emanuel (2013). "Syphilis pathology". Dermnet NZ.

- Wilson, Thomas C.; Legler, Allison; Madison, Kathi C.; Fairley, Janet A.; Swick, Brian L. (2012). "Erythema Migrans". The American Journal of Dermatopathology. 34 (8): 834–837. doi:10.1097/DAD.0b013e31825879be. ISSN 0193-1091. PMID 22722463.

- Soyer, H. Peter; Jakob, Lena; Metzler, Gisela; Chen, Ko-Ming; Garbe, Claus (2011). "Non-AIDS Associated Kaposi's Sarcoma: Clinical Features and Treatment Outcome". PLOS ONE. 6 (4): e18397. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...618397J. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0018397. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3075253. PMID 21533260.

- Antiga, Emiliano; Caproni, Marzia (2015). "The diagnosis and treatment of dermatitis herpetiformis". Clinical, Cosmetic and Investigational Dermatology. 8: 257–265. doi:10.2147/CCID.S69127. ISSN 1178-7015. PMC 4435051. PMID 25999753.

- Huma A. Mirza; Amani Gharbi; William Gossman. (2022). "Dermatitis Herpetiformis". StatPearls at National Center for Biotechnology Information. PMID 29630215.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Last Update: July 11, 2019. - Saleem, Maryam; Iftikhar, Hassaan (2019). "Linear IgA Disease: A Rare Complication of Vancomycin". Cureus. 11 (6): e4848. doi:10.7759/cureus.4848. ISSN 2168-8184. PMC 6684112. PMID 31410331.

- Casarin Costa, Jose Ricardo; Virgens, Anangelica Rodrigues; de Oliveira Mestre, Luisa; Dias, Natasha Favoretto; Samorano, Luciana Paula; Valente, Neusa Yuriko Sakai; Festa Neto, Cyro (2017). "Sweet Syndrome: Clinical Features, Histopathology, and Associations of 83 Cases". Journal of Cutaneous Medicine and Surgery. 21 (3): 211–216. doi:10.1177/1203475417690719. ISSN 1203-4754. PMID 28300447. S2CID 40797905.

- Giang, Jenny; Seelen, Marc A. J.; van Doorn, Martijn B. A.; Rissmann, Robert; Prens, Errol P.; Damman, Jeffrey (2018). "Complement Activation in Inflammatory Skin Diseases". Frontiers in Immunology. 9: 639. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2018.00639. ISSN 1664-3224. PMC 5911619. PMID 29713318.

- "Figures - available via license: CC BY 4.0"

- Grant-Kels, Jane (2007). Color Atlas of Dermatopathology. City: Informa Healthcare. pp. 107, 119. ISBN 978-0-8493-3794-9.

- Carmen Gómez-Mateo, Maria; Monteagudo, Carlos (2013). "Nonepithelial skin tumors with multinucleated giant cells". Seminars in Diagnostic Pathology. 30 (1): 58–72. doi:10.1053/j.semdp.2012.01.004. PMID 23327730.

- Sequeira, Fiona; Gandhi, Suneil (2012). "Named cells in dermatology". Indian Journal of Dermatology, Venereology and Leprology. 78 (2): 207–16. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.93650. PMID 22421663.

This article incorporates material from the article Dermatitis at Patholines, which is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) license.