Hispano-Arabic homoerotic poetry

There is a recurrent presence of homoerotic poems in Hispano-Arabic poetry. Erotic literature, often of the highest quality, flourished in Islamic culture at a time when homosexuality, introduced as a cultural refinement in Umayyad culture,[1] played an important role.

Among the Andalusi kings the practice of homosexuality with young men was quite common; among them, the Abbadid emir Al-Mu'tamid of Seville and Yusuf III of the Nasrid kingdom of Granada wrote homoerotic poetry.[2] The preference for Christian male and female slaves over women or ephebes of their own culture contributed to the hostility of the Christian kingdoms.[3] Also among the Jewish community of al-Andalus homosexuality was even normal among the aristocracy.[4]

The contradiction between the condemnatory religious legality and the permissive popular reality was overcome by resorting to a neoplatonic sublimation, the "udri love", of an ambiguous chastity.[5] The object of desire, generally a servant, slave or captive, inverted the social role in poetry, becoming the owner of the lover, in the same way as happened with courtly love in medieval Christian Europe.[1]

The homoeroticism present in Andalusian poetry establishes a type of relationship similar to that described in ancient Greece: the adult poet assumes an active (top) role against an ephebe who assumes the passive (bottom) one,[6] which came to produce a literary cliché, that of the appearance of the "bozo",[7] which allows, given the descriptive ambiguity of the poems, both in images and grammatical uses, to identify the sex of the lover described.[1] Much of the erotic-amorous poetry of the period is devoted to the cupbearer or wine pourer, combining the bacchic (خمريات jamriyyat) and homoerotic (مذكرات mudhakkarat) genres.[8]

It began to flourish in the first half of the 9th century, during the reign of Abderraman II, emir of Córdoba.[9] The fall of the Caliphate of Córdoba in the eleventh century and the subsequent rule of the Almoravids and the division into the Taifa kingdoms, decentralized culture throughout al-Andalus, producing an era of splendor in poetry.[10] The Almohad invasion brought the emergence of new literary courts in the 12th and 13th centuries. The greater female autonomy in this North African ethnic group led to the appearance of a greater number of female poets, some of whom also wrote poems that sang of feminine beauty.[11]

Context

The civilization developed in the Umayyad Caliphate from Córdoba rivaled and even surpassed that of Christian Europe. After the death of Charlemagne in 814 and the subsequent decline of his Empire, the only city that rivaled Córdoba in Europe was Constantinople, capital of the Byzantine Empire and located at the other end of the continent. The caliphs of Córdoba surpassed their Byzantine contemporaries in culture. Literature, especially poetry, was enthusiastically cultivated, as was the case in all Arab countries; during the period, Arabic came to surpass Latin as a language in works on medicine, astronomy and mathematics; Christians on the peninsula learned Arabic to perfect an expressive and elegant style, and scholars from all over Christian Europe traveled to Toledo or Córdoba for their studies. It is likely that they maintained a superior standard of public administration: many of the Christian and Jewish subjects preferred the rule of the infidels, whose legislation was no more intolerant than Christian laws.[9]

After the Arab conquest in 711 there was a unique flowering in the Iberian peninsula of homoerotic poetry, which repeated a phenomenon of the Islamic world in general, with parallels in the erotic lyric poetry of Iraq, Persia, Afghanistan, India, Turkey and North African countries such as Egypt, Tunisia, and Morocco. Anthologies of medieval Islamic poetry from the great Arab capitals show, over almost a millennium, the same current of passionate homoeroticism found in the poems of Córdoba, Seville or Granada.[9]

Homosexuality, consented to on the basis of a general Koranic tolerance towards sins of the flesh, was introduced as a cultural refinement among the Umayyads, despite the protests of some juridical schools. Thus, Ibn Hazm of Córdoba was tolerant of homoeroticism,[12] showing his reprobation only when it was mixed with some kind of public immorality, an attitude apparently shared by his contemporaries.[1]

Both philosophically and literarily, Greek classicism was known and respected by the Andalusian authors, whose work of translation and compilation was essential in the survival of many classical texts. Many of the themes of Andalusian poetry, such as the praise of ephebic beauty, are directly derived from Greek homoerotic poetry, which they knew through translations from the time of the great library of the Córdoba of the Umayyad caliph Hisham II.[13]

Islamic law and homosexuality

The severity and intolerance that characterized traditional Judaism and Christianity in sexual matters reappeared in the laws of the third Abrahamic religion. Regarding homosexuality, some important schools, such as that of the theologian Malik of Medina or the literalist Ibn Hanbal, contemplated the death penalty, generally by stoning. Other schools of law saw it more fitting to opt for flogging, generally one hundred lashes.[9]

However, other aspects of Islamic culture show some contradiction with the severity, inherited from the Old Testament, which dominated the legality of Islam in this respect. The popular attitude was much less hostile to homoeroticism and European visitors were surprised at the relaxed tolerance of homoeroticism among Arabs, who seemed to find nothing unnatural in relations between men and boys. In medieval Arab treatises on love, this so-called "emotional intoxication" is provoked not only by the love of women, but also by the love of boys and other men.[9] While in the rest of Europe it was punishable by burning at the stake, in al-Andalus homosexuality was common and intellectually prestigious; the work of authors such as Ibn Sahl of Seville, explicit in this sense, was carried to all corners of the Islamic world as an example of love poetry.[14]

Ibn Hazm's only mention of lesbianism in The Ring of the Dove is, in application of Islam, damning. But Arabic references to lesbianism are not so apparently condemnatory: at least a dozen romances between women are mentioned in The Book of Hind, herself an archetypal lesbian; a 9th century Treatise on lesbianism (Kitab al-Sahhakat) has been lost, and later works on Arab eroticism contained chapters on this subject.[15][16] Some women in al-Andalus had access to education and were able to write freely. In their poems, love for another woman is treated and present in the same way as that of male poets for other men.[17]

The Australian historian Robert Aldrich points out that in part this tolerance towards homoeroticism is due to the fact that Islam does not recognize such a marked separation between the flesh and the spirit as Christianity does and has an appreciation for sexual pleasure.[18] Other reasons would be aesthetic: in the Koran it is a man, Yūsuf (the Christian patriarch Joseph), who in surah XII is presented as the maximum representative of beauty. In this Koranic text, the Platonic concept that beauty is what generates love,[1] in a terrible, rapturous way, is also shown. García Gómez points out in his introduction to The Ring of the Dove that Muslims call "al-iftitān bi-l-suwar" the "disorder or commotion that souls suffer when contemplating beauty concretized in harmonious forms," illustrating it with the story of the Egyptian noblewomen who cut their fingers while peeling oranges, snatched by the beauty of Yūsuf.[19]

Among the Andalusian kings the practice of homosexuality with young men was quite common; Abderraman III, Alhaken II (who had offspring for the first time at the age of 46, with a Christian Basque slave girl who cross-dressed, in the fashion of Baghdad, as if she were an ephebus), Abd Allah of the Taifa of Granada, the Nasrid Muhammed VI; among them, the abbot Al-Mu'tamid of the Taifa of Seville and Yusuf III of the Nasrid Kingdom of Granada wrote homoerotic poetry;[2] Abderraman III, Alhaken II, Hisham II and Al-Mu'tamid openly maintained male harems.[20] It is known that the Hispano-Arabs preferred Christian slaves as sexual partners to women or ephebes of their own culture, which provoked the enmity and continuous hostilities of the Christian kingdoms. The martyrdom of the Christian child Pelagius for resisting the wishes of Abderraman III, first Umayyad caliph of Córdoba, for which he was later sanctified, is well known.[3]

Also among the Jewish community of al-Andalus homosexuality was even normal among the aristocracy. To quote from the collective volume Aspects of Jewish Culture in the Middle Ages (1979), in Spain there was "a courtly and aristocratic culture characterized by a romantic individualism (in which there was) an intense exploration of all forms of liberatory sexuality: heterosexuality, bisexuality, homosexuality". Homosexual pleasure was not only frequent, but was considered more refined among the well-to-do and educated; apparently, there is data indicating that Sevillian prostitutes in the early 12th century were paid more than their female counterparts, and had a higher class clientele.[20] Prostitutes were relegated to the urban plebs and especially to the peasants who visited the cities.[4]

Homoeroticism in Andalusian Literature

To overcome the contradiction between religious legality and popular reality, Arabic literature resorted to a curious hadith attributed to Muhammad himself: "He who loves and remains chaste and hides his secret and dies, dies a martyr's death".[9] The poet, apprehender of beauty, was impelled to sing of masculine beauty. The sublimation of courtly love through Neoplatonism, of singing bodily beauty transcended into ideal Beauty, allowed the poet to express his homoerotic feelings without danger of moral censure.[1]

Homosexual love (مذكرات mudhakkarat) as a literary theme occurred in the realm of poetry throughout the Arab world; the Persian jurist and litterateur Muhammad ibn Dawud (868 - 909) wrote, at the age of 16, the Book of the Flower, an anthology of the stereotypes of the love lyric that devotes ample space to homoerotic verses;[18] Emilio García Gómez points out that Ibn Dawud's anguish, due to the homoerotic passion he felt all his life towards one of his schoolmates (to whom he dedicated the book), was a spring that led him to realize a platonism that García Gómez identifies as a "collective yearning" in Arab culture to redirect a "noble spiritual flow" that found no way out. Ibn Dawud clothed it with the Arab myth of "udri love", whose name comes from the tribe of the Banu Udra, which would literally mean "Sons of Virginity": a refined idealism created by Eastern rhetoricians, an "ambiguous chastity", according to García Gómez, which was "a morbid perpetuation of desire".[5]

Both the punitive and sentimental traditions figure in Andalusian literature, and notably in the writings of its best-known love theorist, Abu Muhammad 'Ali ibn Ahmad ibn Sa'id ibn Hazm (994-1064), better known as Ibn Hazm, who says of love in The Ring of the Dove:

It is neither reprobated by faith nor forbidden in the holy Law, since the hearts are in the hands of the Honored and Mighty God, and a good proof of this is that, among the lovers, caliphs and righteous imams are counted.[21]

— Ibn Hazm, The Ring of the Dove

For Ibn Hazm, love escapes man's control, "it is a kind of nature, and man has power only over the free movements of his organs."[22] In The Ring of the Dove, a mixture of theoretical generalizations and personal exemplifications or anecdotes (though the vast majority concern heterosexual love, especially for beautiful female slaves), stories of men falling in love with other men are repeatedly interspersed. At times the attribution is obscure, since the text, referring neutrally to the loved one, may be dedicated to either a man or a woman:[9]

Other signs are: that the lover flies hastily to the place where the beloved is; that he looks for pretexts to sit by his side and get close to him; and that he abandons the works that would force him to be far from him, giving up the serious matters that would force him to separate from him, and is reluctant to leave his side.[23]

— Ibn Hazm, The Ring of the Dove

From the Baghdadi influence of Ibn Dawud, the Andalusians learned the rules of the game of courtly love: the unavailability of the loved one because he or she belongs to another (not because of adultery, but because he or she was generally a slave of another owner); the spy, the favorable friend, the slanderer? are part of a series of pre-established figures that accompanied the lovers in their story.[1]

Another poet who sang of the illicit pleasures of wine and ephebes was Abū Nuwās al-Hasan Ibn Hāni' al-Hakamī, better known simply as Abu Nuwas (Ahvaz, Iran, 747 - Baghdad, 815). The homoerotic love he celebrated is similar to that described in ancient Greece: the adult poet assumes an active role opposite a young adolescent who submits. Interest in ephebes was fully compatible with interest in women; both shared a socially subordinate role, a fact that was emphasized in poetry by showing them as members of an inferior class, or slaves or captive Christians.[6]

Just as the active role was not socially condemned, the adult who took a passive (bottom) role in the homosexual relationship was the object of scorn. Thus, the age difference between lover and beloved was crucial in a homosexual relationship; hence the appearance of facial hair on the ephebe was an extremely popular topos in Arab homoerotic poetry, because it marked the transition to an untenable situation, although it immediately generated a response in defense of the beauty maintained in a fully bearded young man.[6]

Strophes and genres of classical Arabic poetry

Classical Arabic poetry used three basic types of verses or strophic forms: the qasida, a long, monorhymic ode; the qita or quita, a short, monorhymic fragment or poem on a single theme or image; and the muwassah or moaxaja, a strophic form that appeared later. The latter two were usually devoted to matters related to the pleasures of life, descriptions of wine and its consumption, love or expressions of regret for the ephemerality of such pleasures.[24]

The qasida was the usual form for the major genres: the panegyric or madih, in honor or praise of a great man; the elegiac, ritza or martiyya, commemorating the death of a great man; and the satirical genre, hiya or hicha, in which the enemy is ridiculed.[24][25] The erotic genre qasida was known as nasib, and was closely linked with ogniya, verses adapted to song and musical accompaniment, cultivated by numerous female poets.[26] All these genres can be considered, to a certain extent, variants impregnated with the assifat or descriptive genre, due to the exuberant luxury of images and nuances that Andalusian poetry displayed.[25]

Two genres or themes in which homoerotic poetry can be found are the jamriyyat or khamriyyat (bacchic poetry) and the erotic-amorous genre, the ghazal or gazal, which depending on the sex of the object of desire can be known as mu'annathat, if dedicated to a woman, or mudhakkarat, if addressed to young men.[27] A vast majority of this type of poetry refers to the cupbearer, combining the Bacchic and erotic themes.[8]

9th and 10th centuries, Umayyad period

Erotic poetry began to flourish in al-Andalus under the rule of Abderraman II (792-852) in the then Emirate of Córdoba. His grandson, Abd Allah I (844-912), already wrote amorous verses for a "dark-eyed gazelle", according to Ibn Hazm.[9] The ambiguity in grammatical usages extended to the images used to describe the beauty of both ephebes and maidens, making it difficult to know the sex of the lover described. There were, however, some clues, which are sometimes masked in the translations: some terms that in Spanish are feminine words, such as "gazelle" and "moon", in Arabic are masculine.[1] Another indication was the allusion to the facial hair, the bozo,[7] which appears on the face of the ephebus both diminishing his beauty and increasing his attractiveness by evidencing his masculinity:[1]

_-_n._G_0052_-_Gallo_p._23.jpg.webp)

O thou, on whose cheeks the hair has written two lines that,

destroying thy beauty, awaken longing and care!

I knew not that thy gaze was a sabre, till now

I have seen thee wear the tahalis of hair.[29]— Ibn Said al-Maghribi, Banners of the Champions and the Standards of the Distinguished

Ibn Abd Rabbihi (Córdoba, 860-940), poet of the courts of Abd Allah I and Abderramán III and one of the earliest representatives of Andalusian literature,[30] wrote about a young man in the typical mood of submission to the beloved.[9]

I gave him what he asked for, I made him my lord...

Love has put bridles on my heart

like a cameleer puts bridles on his camel.

Another of the themes of Arabic poetry was the bacchic poetry (خمريات jamriyyat), celebrating, despite religious prohibitions, wine and drunkenness; it was sometimes mixed with homoeroticism in the figure of the cupbearer or pourer. Thus, some poets were more explicit and less chaste in the expression of their passion, as Ali ibn Abi l-Husayn (m. 1038):[1]

How many nights I have been served drinks

by the hands of a roe deer that commits me!

He made me drink from his eyes and from his hand

and it was drunkenness upon drunkenness, passion upon passion.

I would take kisses from her cheeks and dip my lips

in her mouth, both sweeter than honey.— Ibn al-Kattānī, Tašbīhāt, nº 177

It was relatively frequent in Arabic love poetry that the object of desire was a slave or captive. It was not uncommon for them to be blond people; Ibn Hazm himself noted that several caliphs were inclined towards the blond color, even that many of them, by maternal inheritance and given this family preference, were blond and blue-eyed.[31] Yusuf ibn Harun ar-Ramadi (926-1013) wrote about a blond slave:[1]

Disturbed by the looks, it would seem to you

that he has just awakened from the slumber of sleep,

whiteness and blondness are associated in beauty,

without being contrary, for they are similar;

as chains of reddish gold on a silver face,

so the aurora, white and blond,

is the one that seems to imitate him.

When the blush appears on his cheeks

it is like pure wine on rock crystal.— Ibn al-Kattānī, Tašbīhāt, nº 233

In another poem, Ar-Ramadi gave proof of his bisexuality by recounting a night of passion with an ephebe and a slave girl:[1] "I stretched out my hand towards the peacock at times and at others I withdrew towards the wood pigeon." Ar-Ramadi, panegyrist of Almanzor and one of the most prominent Cordovan poets of the 10th century, became so enamored of a young Christian that he made the sign of the cross when he drank wine. When his turbulent political career led him to prison, he fell in love with a black slave: "I looked into his eyes and they made me drunk.... I am his slave, and he is my master." This submission and reversal of social roles in Arabic poetry resembles the chivalric romanticism of medieval Christian Europe.[9]

Mention should also be made of Muḥammad ibn Hānī ibn Saˁdūn (c. Seville, 927 - 972) who stood out in the Caliphate of Córdoba for the boldness of his lyric poetry. In his poetry, which combined the classical currents of Bedouin tradition with modernist renovations, he practiced the genre of self-praise or boasting (fajr), displaying both his homosexuality and his ascription to Shiism, a faction of Islam persecuted in his time by the Umayyads.[32]

11th century, the splendor of classical Arabic poetry

The fall of the Umayyad Caliphate and the subsequent fragmentation into the Taifa kingdoms produced an exodus of poets to the various courts that were formed, decentralizing culture throughout al-Andalus. As the number of courts grew, so did the number of poets, and the possibility of the emergence of good creators.[10]

Córdoba

In Córdoba the figure of the extraordinary poet and philologist Abū 'Āmir ibn Šuhayd (992-1035), son of a minister of Almanzor, stood out. Ibn Suhayd presented himself as a cynical and libertine character, which he himself was responsible for disseminating and which may remind one of Lord Byron. He cultivated the modernist genres, which sang of the pleasures of life: love, wine, hunting, the pleasurable feeling of nature, because they reflected his way of life, his evident bacchic and bisexual activity, his attitude against the established. In one of his poems, after describing a party with young women in bloom, a royal pageboy appears, an adolescent and effeminate ephebus:[10]

I followed him to the door of his house,

because you have to follow the piece until you reach it,

I tied him with my reins

and he was docile to my mouthful.

I went to drink at the wells of desire

and passed over the vileness of sin....— Ibn Suhayd, Dīwān, Pellat p. 160-153.

The most acclaimed lyricist of this period is the Cordovan Muhammad ibn Abd al-Malik ibn Quzman, or Ibn Quzman (c. 1080-1160), considered one of the great medieval poets. Tall, blond and blue-eyed, Ibn Quzman was an irreverent bohemian who led and displayed a licentious life. His figure recalls that of the Baghdadi Abu Nuwas at the court of Harun al-Rashid, also completely liberal in his homoeroticism.[33]

I have a tall, white, blond beloved.

Have you seen the moon at night? Well, he shines brighter.

The traitor left me and then he came to see me and to know my news:

he stopped my mouth, he shut my tongue,

he was like a file to my suspicions.

Far from the qasidas and the canons of classical Arabic verse, Ibn Quzman brought to its highest level the zajal, a type of muwashshah or poetry in stanzas that was written in Hispanic dialectal Arabic. In a deliberately popular style and profuse in erotic situations, his zéjels celebrated wine, feasting, and love for women and young girls. Ibn Quzman liked the pleasures of life and being always well dressed, but he hated to work:[34]

Since I was born until now, I have been pleased with the brazenness,

and there are some things that I never lack:

with every drinker and fornicator I get together.

When someone reminded him that whoever is serious in this life will be rewarded with Paradise, the irreverent Ibn Quzman replied to be in Paradise in this life, vindicating his libertine lifestyle:[35]

If they gave me paradise, it would be wine

and love beauties.

There we went, joke and debauchery,

sometimes with young men, sometimes with women;

drinks flowed and it was what it was.

Counselors, stop talking nonsense:

my vice is virtue!

Stricken by poverty at the end of his days, and imprisoned repeatedly accused of heresy for his attitude of defiance to the religious authorities,[36] Ibn Quzman ended his days dedicated to teaching in a mosque. His work is collected in the translation made by Emilio García Gómez of his complete work, Todo Ben Quzman (Gredos, 1972).[2]

Seville

Seville became an independent kingdom, a taifa, under the sovereignty of the Banu 'Abbad, a rich and aristocratic provincial family that ruled with intelligence, lack of scruples, ambition, courage, pride and a high aesthetic sensibility, and that led Seville to be the poetic capital of the Al-Andalus of the Taifa kingdoms. Sevillian poetry acquired a new degree of exquisiteness and formal beauty in the reign of Abbad ibn Muhammad al-Mu'tadid (Seville, ? - id., 1069), King taifa of Seville (1042-1069). One of the best poets of his court, in which the ministers were poets and the poets were ministers, was his own son Muhammad ibn 'Abbad al-Mu'tamid (1040 - 1095). From a very young age he was united by an "equivocal and passionate friendship" with another of the great poets of the time, Abu Bakr ibn Ammar (1031-1086), also known as Ibn Ammar or Abenamar, of whom he was a disciple in Silves. Banished by Al-Mutadid to Zaragoza to avoid the pernicious influence on his son, Ibn Ammar wrote a qasida to the king asking for forgiveness, but perhaps the mention of his amusements and his youthful nights with Al-Mutamid in Silves caused the qasida to have no effect:[10]

When recalling the time of my youth, it is as if it got kindled

the fire of love in my chest.

Those nights when I disregarded the wisdom of advice

and followed the errors of the foolish;

I condemned the drowsy eyelids to sleeplessness

and gathered torment from the tender branches.— Ibn Bassam, Dajira, 3, p. 272-274.

Despite complaining about his fate in Zaragoza, Ibn Ammar was able to dedicate his ghazal, a genre he mastered, to the beautiful ephebes of the court of Ibn Hud al-Mutaman. Upon the death of Al-Mutadid, the new king Al-Mutamid had his former friend and lover brought back, and together they ruled Seville, as king and minister. At the end of their lives their relationship was twisted by a confrontation of Ibn Ammar, then governor of Murcia, with the king of Valencia; Al-Mutamid wrote a satirical qasida, in which he ridiculed Ibn Ammar's humble origins. In the qasida with which the poet answered him, he mocked the Abbadids, Al-Mutamid's wife and children, and accused him of sodomy, recalling the days of Silves:[10]

I embraced your tender waist,

I drank clear water from your mouth.

I was content with what was permitted,

but you wanted that which is not.

I will expose that which you conceal:

Oh glory of chivalry!

You defended the villages,

but you raped the people.— M. J. Rubiera Mata, Al-Mu‘tamid, p. 29 y 36.

When Al-Mutamid was later able to apprehend Ibn Ammar, he pardoned him, but when he learned that the latter was boasting of his pardon, he flew into a rage and killed him with his own hands. After which, however, he mourned him and offered a sumptuous funeral.[9]

Levante

The former officials of the caliphate took over the provinces of the Levante of the Iberian Peninsula, the Sarq al-Ándalus, which with the arrival of the Cordovan elites had a great urban and cultural development. Ibn Jafaya of Alcira (1058-1139) can be considered one of the best modernist poets of al-Andalus. He stood out especially for the development of the modernist theme of the garden (rawdyyāt), to the point that the lyric on nature was called in al-Ándalus, in reference to his surname, jafayyi style. In his poetry he made subtle chaining of images, loaded with connotations to other themes, including homoeroticism; in a rawdiyyat, the description of a garden introduces a smile, an army, the wine in his cup which is a horse and ends in a beautiful young man.[10] Indicative is the use of the term "moon" (of masculine gender in Arabic) to refer to the young man:[1]

The wine is struck down and falls on its face,

expelling from its mouth a violent aroma;

the cup is a sorrel horse that is running in circles,

with a sweat in which bubbles flow;

it runs with the wine and the cup, a moon

with a beautiful face and a honeyed smile;

armed to the nines, in its waist and in its gaze,

there are also weapons and penetrating swords.— Ibn Jafaya, Diwan, p. 254-255

12th and 13th centuries. Almohad period.

The invasion of Al-Andalus by the Almohads (al-Muwahhidūn, "those who recognize the unity of God"), coming from Morocco, provoked the emergence of new literary courts in the 12th and 13th centuries. Along with the emergence of female poets, due to greater female autonomy (perhaps because of an ancient matriarchal tradition) in this North African ethnic group, there was a flourishing of mystical poetry, in which the words of earthly love changed their scope to express the soul's transit to the love of God.[11]

This did not mean the abandonment of love poetry, where homoeroticism continued to be present in a new preciosist form. Emilio García Gómez points out that the metaphors, worn out by use, were lexicalized to later generate new metaphors that could be called "second power" metaphors. Describing an ephebe, in verses that combine the lexicalized comparison of curly water as a coat of mail and the reddish color of oranges, Safwan ibn Idris of Murcia (1165-1202) wrote:

A gazelle full of coquetry,

which sometimes pleases us and sometimes frightens us;

he throws oranges into a pool

like one who stains a coat of mail with blood.

It is as if he throws the hearts of his lovers

into the abyss of a sea of tears.— Al-Kutubī, Wafat al-wafayāt, I, p. 85.

Also noteworthy is the famed Muhammad Ibn Galib, known as al-Rusafi (d. 1177), born in al-Rusafa (present-day Ruzafa, in Valencia) but settled in Málaga.[37] Within the same preciosist phenomenon, al-Rusafi, transposing the theme of the beauty of the ephebos to the description of the artisans, and inverting the lexicalized metaphor of the slenderness of the waist like a branch, said in a poem:

He learned the carpenter's trade, and I said to myself:

"Perhaps he learned it from the sawing of his eyes on the hearts."

Wretched the trunks that he prepares to cut,

sometimes by carving them and sometimes by beating them!

Now that they are wood, they start taking the fruit of their crime,

from when, being branches, they dared to steal the slenderness of their stem.— E. García Gómez, El libro de las banderas, p. 252.

At the court of Sa'īd ibn Hakam of Menorca, a small literary court of Andalusian exiles from the peninsula was also formed, where poets continued this preciosity. One of his guests was Ibn Sahl of Seville (1212-1251). Born Jew, Ibn Sahl became a Muslim, an experience he described through homoerotic poems; thus, loving an ephebe named Musa (Moses), he abandons him for another named Muhammad.[11] One of the poems dedicated to his first lover is a sample of the preciousness of the time and the images of "second power", where the sideburns resemble the legs of scorpions and the eyes resemble arrows or swords:

Is it a sun with a purple

robe or a moon ascending on a willow branch?

Does it show teeth or are they strung pearls?

Are those eyes that it has or two lions?

An apple cheek or a rose

that from scorpions keeps two swords?— Teresa Garulo, Ibn Sahl of Sevilla, p. 53.

Homoerotic poetry by women

Although the situation of Andalusian women was one of seclusion behind the veil and the harem, there were some among the upper classes who, being only daughters or without male siblings, were liberated by remaining single. The arrival of the Almohads in the 12th century also imported a tradition of matriarchal line that granted some freedom to women, favoring their access to education and literary production.[38]

Another sector that could access the gatherings where poetry was created were the non-concubine slaves, freed from the veil and the harem. They were also freer in love: because the Arabs considered it necessary for the beloved to have the freedom to bestow his love, slaves of both sexes assumed, both in literature and in the real world, the role of masters of their lovers, one of the clichés of Arab courtly love. Those most associated with the literary environment were the female singers (qiyan), who received a careful education to satisfy both physically and aesthetically the man. The most prized talent being musical, the female singers learned hundreds of verses and were able to improvise their own compositions.[38]

The love described by the women poets is the cliché of Arab courtly love; in contrast to homoerotic poetry, the beloved is not described physically, with a few exceptions. In many cases their work comes as an echo of the male voice and point of view, and they come to sing the female beauty of others, simulating a sapphic love that some authors doubt had a parallel in real life, as is the case of the sisters Banat Ziyad of Guadix, Hamda and Zaynab,[38] to whom the authors indistinctly attribute the authorship of the poems preserved under their surname. In one of their poems, the passion of one of the sisters for a young girl is expressed, leaving the doubt as to whether it is really homoeroticism or a mere literary cliché:[11]

That is the reason that prevents me from sleeping:

when she lets her curls loose over her face,

she looks like the moon in the darkness of the night;

it is as if the dawn has lost a brother

and sadness has dressed itself in mourning.

It is worth mentioning the figure of Princess Wallada bint al-Mustakfi (994–1077 or 1091), who has been called "the Andalusian Sappho".[39] Daughter of the Caliph of Córdoba Muhammad III, the death of her father in 1025 left her a fortune in inheritance that allowed her to turn her home into a place of passage for writers. She had a scandalous relationship with the poet Ibn Zaidun, in whose anthologies her few poems that have come down to us are usually collected.[40] According to the chronicles, Princess Wallada fell in love with Muhya bint al-Tayyani, daughter of a Cordovan fig seller, and took care of her education until she became a poet. A lesbian relationship between them is supposed, but there is no evidence of it.[41]

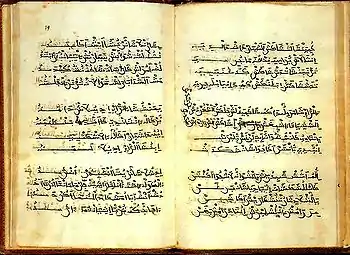

Translations and anthologies

Although love poems dedicated to young men are numerous in Andalusian literature, Andalusian homoeroticism has been a scarcely studied subject, and the loss of materials (especially from the Nasrid period) was enormous, due to the blind destruction at the hands of the conquering Christians, such as the great burning of manuscripts ordered by Cardinal Cisneros.[42] Christians exaggerated the extent of Andalusian debauchery, especially homosexual practices; they considered it a disease, superficially very attractive, but not only contagious, but incurable. Although in the 14th century the Nasrid Kingdom of Granada posed no threat to Castile, there was an exaggerated fear of invasions from the south. This attitude lasted until the contemporary age; according to Claudio Sánchez-Albornoz, "without the Reconquest, homosexuality, so practiced in Moorish Spain, would have triumphed".[43]

Daniel Eisenberg mentions the presence of a small anthology "in the chapter "Perversión" of Claudio Sánchez-Albornoz's homophobic book, De la Andalucía islámica a la de hoy (1983)"; he also highlights Emilio García Gómez's Poemas arabigoandaluces, published at a time of liberalization in the late 1920s, as the first collection to reach general attention; as well as his translation of the complete works of Ibn Quzman, Todo Ben Quzman (Gredos, 1972); and a third collection translated by García Gómez, El libro de las banderas de los campeones.[2]

The Real Biblioteca de San Lorenzo de El Escorial also contains homoerotic texts in Arabic: El abandono del pudor y el primer bozo de la mejilla; Excusas sobre el amor del primer bozo en la mejilla; and El jardín del letrado y las delicias del hombre inteligente.[44]

See also

References

- Rubiera Mata (1992). "III. La poesía árabe clásica en al-Andalus: época omeya".

- Eisenberg. 1996, p.56-57

- Eisenberg. 1996, p.64

- Eisenberg. 1996, p.59-60

- Ibn Hazm. 1967, p. 69-70

- "glbtq >> literature >> Middle Eastern Literature: Arabic". 2010-06-15. Archived from the original on 15 June 2010. Retrieved 2022-04-27.

- Bozo: (From lat. buccĕus, from the mouth). m. Hair that points to the young men on the upper lip before the beard is born.

- del Moral, Celia (1998). "Contribución a la historia de la mujer a partir de las fuentes literarias". La sociedad medieval a través de la literatura hispanojudía: VI Curso de Cultura Hispano-Judía y Sefardí de la Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha. Univ de Castilla La Mancha. ISBN 9788489492967.

- Crompton. 1997, p.142-161

- Rubiera Mata (1992). "IV. La poesía árabe clásica: el esplendor (Siglo XI)". Cervantes Virtual.

- Rubiera Mata (1992). "V. La poesía árabe clásica en al-Andalus III: el dorado crepúsculo (Siglos XII-XIII)". Cervantes Virtual.

- Ibn Hazm, 1967. p. 290

- Reina. 2007, p. 73

- Reina. 2007 p. 72-73

- Crompton. 2006, p.166

- Crompton. 1997, p.150

- Eisenberg, Daniel (1999). "Introduction". Spanish writers on gay and lesbian themes: a bio-critical sourcebook. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 17. ISBN 9780313303326.

- Aldrich. 2008, p.274

- Ibn Hazm. 1967, p. 67

- Reina. 2007 p. 81

- Ibn Hazm. 1967, p. 109

- Ibn Hazm. 1967, p. 154

- Ibn Hazm. 1967, p. 118

- Scheindlin, Raymond (1998). "La situación social y el mundo de valores de los poetas hebreos". La sociedad medieval a través de la literatura hispanojudía: VI Curso de Cultura Hispano-Judía y Sefardí de la Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha (in Spanish). Univ de Castilla La Mancha. p. 59. ISBN 9788489492967.

- de Eguilaz y Yanguas. 1864 p.47-60

- de Eguilaz y Yanguas. 1864 p.57

- Starkey, Paul (1998). "Abu Nuwas". Encyclopedia of Arabic Literature. Taylor & Francis. pp. 41–42. ISBN 9780415185714.

- Rubiera Mata. 1989, p.22

- Ibn Said al-Maghribi. 1978, p. 191

- Chejne, Anwar G. (1999). Historia de España musulmana. Guida Editori. p. 182. ISBN 9788437602257.

- García Gómez. 1978, p. 141

- Andú Resano, Fernando (2007). El esplendor de la poesía en la Taifa de Zaragoza (in Spanish). Zaragoza: Mira. ISBN 978-84-8465-253-3.

- Crompton, Louis (2006). Homosexuality & Civilization. Harvard University Press. p. 167. ISBN 9780674022331.

- den Boer and Sierra Martínez. 1992, p.39

- den Boer and Sierra Martínez. 1992, p.45

- den Boer and Sierra Martínez. 1992, p.49

- Itinerario cultural de Almorávides y Almohades: Magreb y península ibérica (in Spanish). Fundación El legado andalusì. 1999. p. 375. ISBN 9788493061500.

- Rubiera Mata. 1989, «Introducción»

- de Eguilaz y Yanguas, Leopoldo (1864). Poesía histórica, lírica y descriptiva de los árabes andaluces. Discurso leído antre el claustro de la Universidad Central de Madrid (in Spanish). Universidad Complutense de Madrid: Imprenta de Manuel Galiano.

- Wilson, Katharina M. An Encyclopedia of continental women writers, Vol. 1.

- Rubiera Mata. 1989, p.107

- Eisenberg. 1996, p. 54-55

- Eisenberg. 1996, p. 62-63

- Eisenberg. 1996, pp.57-58

Bibliography

- Aldrich, Robert (2008). Gays y lesbianas: vida y cultura: Un legado universal (in Spanish). Editorial NEREA. ISBN 9788496431195.

- Crompton, Louis (1997). "Male Love and Islamic Law in Arab Spain". In Murray, Stephen O.; Roscoe, Will (ed.). Islamic homosexualities: culture, history, and literature. New York University Press. ISBN 9788489678606.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link)

- Crompton, Louis (2006). Homosexuality & Civilization. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674022331.

- den Boer, Harm; Sierra Martínez, Fermín (1992). El Humor en España. Volumen 10 de Diálogos hispánicos de Amsterdam (in Spanish). Rodopi. ISBN 9789051833980.

- de Eguilaz y Yanguas, Leopoldo (1864). Imprenta de Manuel Galiano (ed.). Poesía histórica, lírica y descriptiva de los árabes andaluces. Discurso leído antre el claustro de la Universidad Central de Madrid (in Spanish). Universidad Complutense de Madrid.

- Eisenberg, Daniel (1996). "El Buen Amor heterosexual de Juan Ruiz". Los territorios literarios de la historia del placer (in Spanish). Huerga y Fierro Editores. ISBN 9788489678606.

- García Gómez, Emilio (1978). El libro de las banderas de los campeones de Ibn Said al-Maghribi (in Spanish). Barcelona: Seix Barral. ISBN 9788432238406.

- Ibn Hazm (1967). Emilio García Gómez (ed.). El collar de la paloma (in Spanish). Sociedad de Estudios y Publicaciones.

- Reina, Manuel Francisco (2007). Antología de la poesía andalusí (in Spanish). EDAF. ISBN 9788441418325.

- Rubiera Mata, Mª Jesús (1992). Literatura hispanoárabe (in Spanish). Madrid: Mapfre.

- Rubiera Mata, Mª Jesús (1989). Poesía femenina hispanoárabe (in Spanish). Castalia. ISBN 9788470395697.