Obturator hernia

An obturator hernia is a rare type of hernia, encompassing 0.07-1% of all hernias,[2] of the pelvic floor in which pelvic or abdominal contents protrudes through the obturator foramen. The obturator foramen is formed by a branch of the ischial (lower and back hip bone) as well as the pubic bone. The canal is typically 2-3 centimeters long and 1 centimeters wide, creating a space for pouches of pre-peritoneal fat.

| Obturator hernia | |

|---|---|

| |

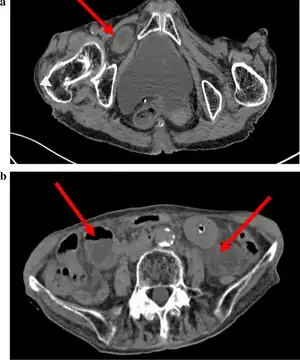

| Abdominal CT scan showing obturator hernia[1] | |

| Specialty | General surgery Hernia |

| Symptoms | bowel obstruction |

| Usual onset | rapid |

| Risk factors | multiparous, underweight, old age, female |

| Diagnostic method | Howship-Romberg sign, abdominal CT scan, Hannington-Kiff sign |

| Differential diagnosis | colon cancer, small bowel obstruction, small bowel hernia |

| Treatment | surgery, laparoscopic hernia repair |

| Frequency | Rare (0.07-1% of all hernias) |

Etiology

Due to differences in width and inclination of the female pelvis and the larger diameter of the female obturator foramen compared to male anatomy,[3] this hernia is more common in persons assigned female at birth, especially multiparous and older females who are severely underweight for their age and height.[2][4] The female obturator foramen has been shown to have a triangular opening, while for males it is more oval-like. Childbirth has also been shown to cause multiple structural changes to the muscle, thereby increasing the risk of hernias forming with multiple childbirth.[4] People with lean body builds are also more likely to develop an obturator hernia due to having less adipose and lymphatic tissue surrounding the obturator canal.[2] Nerves and blood vessels that pass through the obturator canal are covered and protected by adipose tissue. When a person experiences significant weight loss due to malnutrition or chronic illness, this protective fatty tissue is lost allowing pelvic and abdominal contents to shift around and increasing the risk of an obturator hernia. Other factors that may increase a person's risk of developing obturator hernia include conditions that increase pressure within the abdomen. Examples of such conditions are: constipation, multiparity, ascities and chronic pulmonary disease (COPD).[1]

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is often made during laparoscopic pelvic exploration after the person arrives at the hospital with signs and symptoms consistent with bowel obstruction. Laparoscopic pelvic exploration is a minimally invasive procedure that allows the surgeon to visually examine the contents of the abdomen without making a large cut.[5] The Howship–Romberg sign is suggestive of an obturator hernia, with about 56.2% (out of 146 patients in a systematic review) of people showing these signs.[2] These signs are worsened by thigh extension, medial rotation and abduction.[6] It is described as a sharp, stabbing pain in the medial thigh/obturator distribution, extending to the knee and is caused by the hernia pushing on the obturator nerve. The Hannington-Kiff sign can also be suggestive of an obturator hernia, which tests the adductor muscle reflex with a hammer whilst applying pressure on the obturator nerve.[7] However, due to its rare form, obturator hernias are difficult to diagnose due to many other possibilities, non-specific symptoms of pain, as well as minimal external signs/symptoms that can be seen without imaging. The current gold-standard for diagnosis of an obturator hernia is through abdominal computed tomography scans (CT scans), which has been used for diagnosis of 84.2% of patients in a recent systematic review for obturator hernias.[2]

Due to the rarity of an obturator hernia, multiple other illnesses may be considered and ruled out before arriving at the diagnosis of an obturator hernia. Intestinal obstruction is the most common other illness that medical teams may suspect a person has, alongside small bowel obstruction, colon cancer, and small bowel hernia.[8]

Prognosis

Due to the rare nature of the obturator hernia, the causes of the hernia is not widely studied, and therefore it is not preventable.

The difficulty of recognizing and diagnosing obturator hernias often leads to delays in treatment. Since surgical treatment of most cases is delayed, the obturator hernia potentially has the highest mortality rate of the abdominal wall hernias.[9] Studies have shown that if untreated, the mortality rate may range from 50-70%. [10]

When a person with increased risk of obturator hernia presents with bowel obstruction, the obturator hernia must be considered. Aging and malnutrition are common factors that can contribute to obturator hernias. [11] Peritoneal fat and lymphatic tissue that acts as a protective layer over the obturator canal will thin out over time, which results in a larger space between the nerves and vessels, creating the space for the hernia to occur. Additionally, conditions that increase intraabdominal pressure can result in relaxation of the peritoneum. [12] Obturator hernias occur more frequently on the right side compared to the left side because the sigmoid colon physically blocks the left obturator foramen, preventing the formation of the hernia.

The formation of an obturator hernia occurs in three stages: the prehernial stage, the developmental stage, and the third stage.[13] During the prehernial stage, preperitoneal fatty tissue enters the opening of the obturator canal. During the developmental stage, the changes from the prehernial stage progress to a hernial sac. This hernial sac may contain the appendix, fallopian tube, omentum, small intestine, or large intestine. The third stage of obturator hernia formation is often characterized with clinical symptoms as a result of an organ entering the obturator canal.[14] Further development of the hernial sac can potentially put pressure on and potentially damage the obturator nerve. A common complication due to delay in treatment is strangulation.[15]

Diagnosis of the obturator hernia often happens during the third stage or strangulation, at which point emergency surgery is the primary treatment to prevent mortality.[15]

Treatment

Given the high likelihood of bowel strangulation associated with obturator hernia, the treatment would be a surgical intervention. Due to the specific anatomical location of the obturator hernia, the surgery would be classified as an emergency procedure.[15]

Laparoscopic approach

Laparoscopic hernia repair is a minimally invasive technique which allows for good visualization of the hernia and potential simultaneous treatment of other abnormalities within the abdomen.[16] Most published case reports have adopted a transabdominal preperitoneal (TAPP) approach. This technique allows the surgeon to check inside the hernia to see if any section of the bowel is trapped or pinched. Based on the surgeon's clinical judgement, a bowel resection may be performed laparoscopically or through conversion to an open operation.[15]

The laparoscopic method, particularly the TAPP repair, first involves creating a pneumoperitoneum. This is typically done using the open Hassen technique. The ports are then strategically positioned about 5cm from the central line just below the umbilicus. The positioning is crucial, especially when assessing the opposite side during a unilateral obturator hernia diagnosis. This is because there is a possibility simultaneous hernias may be overlooked in such cases. [8]

Once the hernial sac becomes visible, it's carefully placed back, with meticulous dissection if needed. The contents within the hernia, especially any bowel portion would be examined. In cases where a section of the bowel is present, a surgical removal might be warranted, following standard surgical procedures. Sometimes, the extra hernial sac is left as is to avoid over-dissecting. [15]

Open approach

The open surgical procedure for a strangulated hernia would involve a lower midline laparotomy. Through this incision, the hernia is located and its internal contents would be examined by the surgeon. The decisions about potential removal and anastomosis are made. Following this, the hernial opening gets fixed either using direct stitching or by inserting a mesh.[17] While alternative techniques such as the retropubic and inguinal methods exist, they're best done by surgeons well-versed in these particular procedures. The lower central abdominal incision remains a prevalent choice due to its widespread familiarity and reduced risked of complications.[18]

Mesh repair

Towards the end of the process, a mesh may be placed to reinforce the repaired area. Using a synthetic mesh to reinforce the repair has become more common, especially in recurrent or larger defects. This involves making a cut on the front side of the stomach using an electrical surgical instrument. This cut is deepened carefully in order to allow the surgeon to gently separate the lining of the abdominal cavity from the underlying fatty tissue. When there is enough space, the mesh will be placed. Finally, the last step is to stitch the lining of the abdominal cavity back in place. The mesh distributes tension across the repaired area and is intended to both seal and strengthen the area to prevent future hernias.[15] Most hernias, including obturator hernias, have a strong rate of recurrence. After clinical intervention, mesh vs. non-mesh repair are two of the most common ways to finish the procedure. In a recent meta-analysis and systematic review of 1760 studies regarding obturator hernias, it was found that recurrence rates with mesh repair had a 31% chance of recurring, showing statistical significance with 95% confidence interval. However, mortality rates using mesh and non-mesh repair showed a non-significant 64% chance of mortality when compared across 11 studies and cases.[19]

Post-operative care

The road to recovery after surgical correction of an obturator hernia may vary from person to person depending on the severity of their hernia, any other simultaneous procedures done during surgery and individual hospital protocols. Although there are multiple different treatment approaches, many hospitals will follow their institution's guidelines for emergency hernia repair.[15] Post-surgery care for obturator hernias may also include protocols to aid in recovery of bowel resections as this is a procedure that may be performed in the process of treating the hernia but is not always necessary. Common post-operative approaches include bowel rest, pain management and wound care.

Bowel rest is a term often used by clinicians to describe a period that involves consumption of non-solid foods in order to give the digestive tract an opportunity to rest and recover. People on bowel rest may be asked to drink only clear liquids or to avoid consuming food and drink entirely. In the later case, nutrition will be provided by an intravenous line, often called an IV line.

Pain management is an important aspect to consider to help someone who has just undergone hernia repair. Keeping pain levels low encourages movement which may help speed up the healing process. The degree of pain a person may feel depends on the extent of their surgery. There is not an official guideline adopted across all hospitals for how to approach pain management in people who are recovering from hernia repair, however a search of different hospital protocols shows that over-the-counter pain relievers such as ibuprofen (commonly known as Advil or Motrin) and acetaminophen (Tylenol) are commonly recommended.[20][21] Stronger pain relievers may also be prescribed by the medical team if it is necessary. In addition to medications, applying ice or heat may help to decrease pain.

Wound care is another topic that varies based on the situation. Specific instructions on how to care for a person's wound should be discussed during their post operation visit with their medical doctor.

Because of its rarity, there is no universal protocol on the timeline for follow-up visits for repair of an obturator hernia. When a person will come back for a follow-up appointment will depend on the clinical expertise of their surgical team. Often times people will be asked to return at 2 and 6 weeks after their surgery for the medical team to track the healing progress and help correct any pain or comfort issues.

References

- Li Z, Gu C, Wei M, Yuan X, Wang Z (March 2021). "Diagnosis and treatment of obturator hernia: retrospective analysis of 86 clinical cases at a single institution". BMC Surgery. 21 (1): 124. doi:10.1186/s12893-021-01125-2. PMC 7941974. PMID 33750366.

- Schizas D, Apostolou K, Hasemaki N, Kanavidis P, Tsapralis D, Garmpis N, et al. (February 2021). "Obturator hernias: a systematic review of the literature". Hernia. 25 (1): 193–204. doi:10.1007/s10029-020-02282-8. PMID 32772276. S2CID 221070627.

- Losanoff JE, Richman BW, Jones JW (May 2002). "Obturator hernia". Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 194 (5): 657–663. doi:10.1016/S1072-7515(02)01137-7. PMID 12022607.

- Dhital B, Gul-E-Noor F, Downing KT, Hirsch S, Boutis GS (July 2016). "Pregnancy-Induced Dynamical and Structural Changes of Reproductive Tract Collagen". Biophysical Journal. 111 (1): 57–68. Bibcode:2016BpJ...111...57D. doi:10.1016/j.bpj.2016.05.049. PMC 4944529. PMID 27410734.

- Chitrambalam TG, Christopher PJ, Sundaraj J, Selvamuthukumaran S (September 2020). "Diagnostic difficulties in obturator hernia: a rare case presentation and review of literature". BMJ Case Reports. 13 (9): e235644. doi:10.1136/bcr-2020-235644. PMC 7493113. PMID 32933908. S2CID 221745984.

- Yamashita K, Hayashi J, Tsunoda T (June 2004). "Howship-Romberg sign caused by an obturator granuloma". American Journal of Surgery. 187 (6): 775–776. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2003.10.020. PMID 15191874.

- Hannington-Kiff JG (January 1980). "Absent thigh adductor reflex in obturator hernia". Lancet. 1 (8161): 180. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(80)90664-9. PMID 6101635. S2CID 3256825.

- Nakayama T, Kobayashi S, Shiraishi K, Nishiumi T, Mori S, Isobe K, Furuta Y (September 2002). "Diagnosis and treatment of obturator hernia". The Keio Journal of Medicine. 51 (3): 129–132. doi:10.2302/kjm.51.129. PMID 12371643. S2CID 23526333.

- Mnari W, Hmida B, Maatouk M, Zrig A, Golli M (2019). "Strangulated obturator hernia: a case report with literature review". The Pan African Medical Journal. 32: 144. doi:10.11604/pamj.2019.32.144.14846. PMC 6607289. PMID 31303916.

- Rizk TA, Deshmukh N (June 1990). "Obturator hernia: a difficult diagnosis". Southern Medical Journal. 83 (6): 709–712. doi:10.1097/00007611-199006000-00031. PMID 2192470.

- Park J (August 2020). "Obturator hernia: Clinical analysis of 11 patients and review of the literature". Medicine. 99 (34): e21701. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000021701. PMC 7447413. PMID 32846788.

- Cai X, Song X, Cai X (2012). "Strangulated intestinal obstruction secondary to a typical obturator hernia: a case report with literature review". International Journal of Medical Sciences. 9 (3): 213–215. doi:10.7150/ijms.3894. PMC 3298012. PMID 22408570.

- Skandalakis LJ, Androulakis J, Colborn GL, Skandalakis JE (February 2000). "Obturator hernia. Embryology, anatomy, and surgical applications". The Surgical Clinics of North America. 80 (1): 71–84. doi:10.1016/s0039-6109(05)70398-4. PMID 10685145.

- Petrie A, Tubbs RS, Matusz P, Shaffer K, Loukas M (July 2011). "Obturator hernia: anatomy, embryology, diagnosis, and treatment". Clinical Anatomy. 24 (5): 562–569. doi:10.1002/ca.21097. PMID 21322061. S2CID 205536085.

- Mahendran B, Lopez PP (2023). "Obturator Hernia". StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. PMID 32119416. Retrieved 2023-07-27.

- Yokoyama Y, Yamaguchi A, Isogai M, Hori A, Kaneoka Y (February 1999). "Thirty-six cases of obturator hernia: does computed tomography contribute to postoperative outcome?". World Journal of Surgery. 23 (2): 214–6, discussion 217. doi:10.1007/pl00013176. PMID 9880435. S2CID 25813779.

- Sze Li S, Kenneth Kher Ti V (January 2012). "Two different surgical approaches for strangulated obturator hernias". The Malaysian Journal of Medical Sciences. 19 (1): 69–72. PMC 3436498. PMID 22977378.

- Petrie A, Tubbs RS, Matusz P, Shaffer K, Loukas M (July 2011). "Obturator hernia: anatomy, embryology, diagnosis, and treatment". Clinical Anatomy. 24 (5): 562–569. doi:10.1002/ca.21097. PMID 21322061. S2CID 205536085.

- Burla MM, Gomes CP, Calvi I, Oliveira ES, Hora DA, Mao RD, et al. (August 2023). "Management and outcomes of obturator hernias: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Hernia. 27 (4): 795–806. doi:10.1007/s10029-023-02808-w. PMID 37270718. S2CID 259064845.

- "Post-Surgery Hernia Pain | Information On Relief For Abdominal Pain After Hernia Surgery". University Hospitals. Retrieved 2023-07-30.

- "Post Operative Instructions: Hernias". University of North Carolina Health. July 29, 2023. Retrieved July 29, 2023.