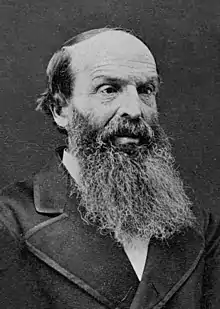

Henry H. Spalding

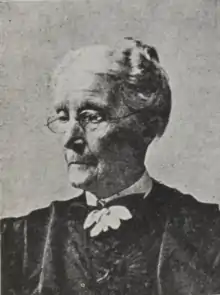

Henry Harmon Spalding (1803–1874) and his wife Eliza Hart Spalding (1807–1851) were prominent Presbyterian missionaries and educators working primarily with the Nez Perce in the U.S. Pacific Northwest. The Spaldings and their fellow missionaries were among the earliest Americans to travel across the western plains, through the Rocky Mountains and into the lands of the Pacific Northwest to their religious missions in what would become the states of Idaho and Washington. Their missionary party of five, including Marcus Whitman and his wife Narcissa and William H. Gray, joined with a group of fur traders to create the first wagon train along the Oregon Trail.[1]

Henry H. Spalding | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | November 26, 1803 |

| Died | August 3, 1874 |

| Spouse(s) | Eliza Hart (d. 1851) Rachel Jane Smith |

| Church | Presbyterian |

Life

Spalding was born in Bath, New York, in either 1803 or 1804. He graduated from Western Reserve College in 1833, and entered Lane Theological Seminary in the class of 1837. He left, without graduation, upon his appointment in 1836 by the Boston-based American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM) as a missionary to the Nez Perce Indians of Idaho.

Eliza Hart was born August 11, 1807, to Levi Hart and Martha Hart (they were first cousins) in Kensington, Connecticut. In 1820 the family moved to Oneida County, New York. She was introduced to Henry by a mutual acquaintance who said that Henry "wanted to correspond with a young lady."[2] The couple were pen pals for about a year, and the relationship quickly deepened after they met in the fall of 1831. Eliza was as interested in participating in missionary work as was Spalding. They married on October 13, 1833, in Hudson, New York.

Mission in the west

Journey

The Spaldings searched for a missionary station through the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, and were initially assigned to the Osage in Missouri. Narcissa Prentiss Whitman knew Henry, as they had attended the same church in Prattsburgh, New York, in the 1820s. Henry met Marcus Whitman in December 1835, and in February 1836 persuaded him to go instead to the Oregon Country. After praying on it, Eliza agreed. On February 29 in Pittsburgh they boarded the steamboat Arabian for Cincinnati, Ohio, arriving four days later, where they waited for the Whitmans. On March 22 they all boarded the steamboat Junius to St. Louis. Changing to the Majestic in mid-trip to avoid travel on the sabbath, they arrived March 29. Two days later they boarded another boat to Liberty, Missouri, with the journey taking another week.

In Liberty, the missionary group waited for the rest of their travel party, a group of fur traders with whom they would travel as far as the continental divide. After some logistical complications, on May 25 they joined the Rocky Mountain Fur Company caravan led by mountain men Milton Sublette and Thomas Fitzpatrick.[3] The fur traders had seven wagons, each pulled by six mules. An additional cart drawn by two mules carried Sublette, who had lost a leg a year earlier and walked on a "cork" leg made by a friend. The combined group arrived at the fur-trader's rendezvous on July 6. Eliza and Narcissa were the first Euro-American women to make this overland trip.

In July 1836, while the company paused at the Rendezvous in the Wind River Mountains of Wyoming, Spalding wrote a letter to a fellow minister and newspaper editor about the journey west. The letter, preserved in a transcript by the "Library of Western Fur Trade Historical Source Documents", provides one of the earliest first hand accounts about the route west and conditions found during this journey across the North American continent.

The Pacific Northwest

Leaving the association of the fur traders, the group of missionaries continued on to the Pacific Northwest. They reached Fort Hall on August 3, and Fort Boise (near Caldwell, Idaho) on August 19. Eleven days later they were at Fort Walla Walla, then operated by the Canada-based Hudson's Bay Company. After a trip further down the Columbia River to Fort Vancouver for supplies, they backed down the trail to Lapwai near present-day Lewiston, Idaho. The Spaldings finally settled into their new home on November 29, 1836. The Whitman party continued on to establish a mission in Waiilatpu, Washington.

When the Spaldings established their mission to the Nez Perce, they also established the first European American home in what is today the state of Idaho. They were also responsible, in 1839, for bringing the first printing press into the territory. Spalding was generally successful in his interaction with the Nez Perce, baptizing several of their leaders and teaching tribal members. He developed an appropriate written script for the Nez Perce language, and translated parts of the Bible, including the entire book of Matthew, for the use of his congregation.

Eliza Spalding was very well liked by the Nez Perce peoples, whose women often followed her around her home wanting to see how the "white woman" cooked, cleaned, dressed, and cared for her children. She was quickly liked by them and respected for her courage and for her attempts to act as a buffer between the Nez Perce and Henry, who was not always as well liked. He was inflexible on gambling, liquor, and polygamy and reproved many people and even went as far as whipping some Nez Perce or having them whip each other. This led to him being ridiculed and denounced by some. Henry was the opposite of Eliza in his relationship with the Nez Perce; where she sought to understand them, he sought for them to understand him.[4] Similarly, the relationships with Spalding's fellow missionaries were also less than ideal. Amid criticism by Whitman and others in the region, Spalding was dismissed by the American Board in 1842, although he never left his mission or stopped his missionary work. He was reinstated following a review by the Board.

Whitman massacre

On November 29, 1847, Marcus and Narcissa Whitman and twelve male emigrants (ten adult men and two boys of 15 and 18) of their mission at Waiilatpu, Washington were killed at the hands of several Cayuse. The natives blamed them for introducing deadly diseases, including the measles, as the tribe had experienced a recent epidemic and a number of children had died. The Spaldings' daughter Eliza, who was staying at the Whitman's mission school, escaped injury along with 45 other women and children. Little Eliza served as a translator, as she was the only survivor knowing Nez Perce. Two days later en route to the Whitmans', Spalding learned of the murders from Catholic priest John Baptist Brouillet, who had heard what had happened and had gone to the mission to assist with the burials. He warned Spalding that he too might be in danger. Spalding secured some provisions from the priest and headed for Fort Walla Walla.[5] Spalding was able to rejoin his family at Lapwai, Idaho| where they had found shelter with William Craig and the Nez Perce, who held the Spaulding party as "hostages for peace". From there, he wrote Bishop Francis Norbert Blanchet, requesting he use his influence to forestall any military reprisals.[6]

After a tense month negotiating the release of the massacre survivors, protected by some friendly Nez Perce, the Spalding family evacuated down the Columbia to Oregon City, Oregon. The Spaldings were brought into the home of Alvin T. Smith in what is now Forest Grove, Oregon. They stayed with the Smiths for a few months while the ABCFM was notified (via ship). After reaching safety, Spalding was less eager for peace. His brother-in-law joined the punitive expedition, and Spalding pledged $500 from the American Board for its expenses.[7] Concerned over continuing violence between Native Americans and settlers in the area, and against Spalding's wishes, the ABCFM decided to make the abandonment of the mission permanent.

He was much discomfited when his letter to Bishop Blanchet became public and blamed Blanchet. Upon further reflection, Spalding, who had long held deep-seated feelings against Catholics, decided that they were behind the massacre. When the Oregon Spectator refused to become embroiled in a religious dispute, Spalding published his views in the short-lived Oregon American and Evangelical Unionist. Peter Hardeman Burnett responded with a rebuttal in the August 1848 issue. Father Brouillet, who had warned Spalding at some considerable risk, felt Spalding most ungrateful. Brouillet's account was printed in the New York Freeman's Journal.[8]

The Spaldings built a small home in the area, while Eliza became the first teacher at Tualatin Academy, which eventually grew into Pacific University. Henry served as an academy trustee for many years. In May 1849 they relocated to Brownsville, Oregon, in the south end of the Willamette Valley and established a homestead in modern North Brownsville. Spaulding served as pastor of the Congregational Church. He was also postmaster and acted as commissioner of common schools for Oregon between 1850 and 1855. Eliza died on January 7, 1851. On May 15, 1853, Henry married Rachel Smith, the sister-in-law of Oregon missionary John Smith Griffin, who had arrived the previous fall.

In his last years, Henry's employment depended on his church funding sponsorships and relations with the U.S. Indian Affairs agent. To his great delight, he returned to the Nez Perce in September 1859, and to Lapwai in 1862. In the late 1860s, he was back in Brownsville. He blamed much of his difficulties in the mission field on the Catholic Church, and on the federal government. He felt strongly enough about the latter that, in October 1870, he took a steamship to San Francisco, then rode the new transcontinental railroad to Chicago, then to his birthplace, to New York City, Boston, and Washington, D.C. In March 1871, he testified before the US Senate. He did not return to the Northwest until September. In 1871 he created a federally sponsored Indian school under the Peace Policy to the Indians sponsored by Ulysses S. Grant. Under the auspices of the Presbyterian Board of Missions, Spalding also continued missionary work with native tribes in northwestern Idaho and northeastern Washington territories. He died in Lapwai, Idaho, August 3, 1874.

The Spaldings had four children: Eliza Spalding Warren,[9] Henry, Martha, and Amelia Spalding Brown. Eliza and Henry were the eldest; Amelia, the youngest. Eliza Hart Spalding was buried in Brownsville, in 1851. Over sixty years later, her remains were disinterred for reburial beside her husband at Lapwai, Idaho.

The village of Spalding, Idaho, located in Nez Perce County, was named after Spalding who taught the Nez Perce, among other things, how to use irrigation and cultivate the potato.[10]

Archival collections

The Presbyterian Historical Society in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, has a collection of eight original letters of Henry and Eliza Spalding to family members.

The Spokane Public Library also has a large collection of correspondence, articles and transcripts relating to his personal life and his career as a missionary.

Whitman College in Walla Walla, Washington, has a large collection of materials relating to the Spalding family.

References

- Gaston, Joseph, The Centennial History of Oregon, 1811–1911 Vol. 1, p. 255, Chicago: Clarke, 1912.

- Drury, Clifford Merrill (1936). Henry Harmon Spalding: Pioneer of Old Oregon. Caldwell, Idaho: Caxton Printers. p. 42.

- Nunis, Doyce B. Jr., Milton G. Sublette, featured in Trappers of the Far West, Leroy R. Hafen, editor., 1972, Arthur H. Clark Company, reprint University of Nebraska Press, October 1983. ISBN 0-8032-7218-9

- "Founding Mother: Eliza Hart Spalding and the Spalding Mission". Women in Idaho History. Wordpress. 2 May 2011. Retrieved 27 July 2013.

- Drury 1936, p. 337.

- Drury 1936, p. 345.

- Drury 1936, p. 346.

- Drury 1936, p. 357.

- "Morning Oregonian. (Portland, Or.) 1861-1937, June 26, 1919, Page 7, Image 8 « Historic Oregon Newspapers".

- Rees, John E. (1918). Idaho Chronology, Nomenclature, Bibliography. W.B. Conkey Company. p. 114.

Further reading

- Dawson, Deborah Lynn. "Laboring in My Savior's Vineyard: The Mission of Eliza Hart Spalding." Dissertation, Bowling Green State University, August 1988.

- Smith, Alvin T. Original diaries at Pacific University Archives

.jpg.webp)