Henry Clifford, 10th Baron Clifford

Henry Clifford, 10th Baron Clifford KB (c. 1454 – 23 April 1523)[1] was an English nobleman. His father, John Clifford, 9th Baron Clifford, was killed in the Wars of the Roses fighting for the House of Lancaster when Henry was around five years old. A local legend later developed that—on account of John Clifford having killed one of the House of York's royal princes in battle, and the new Yorkist King Edward IV seeking revenge—Henry was spirited away by his mother. As a result, it was said, he grew up ill-educated, living a pastoral life in the care of a shepherd family. Thus, ran the story, Clifford was known as the "shepherd lord". More recently, historians have questioned this narrative, noting that for a supposedly ill-educated man, he was signing charters only a few years after his father's death, and that in any case, Clifford was officially pardoned by King Edward in 1472. It may be that he deliberately avoided attracting Yorkist attention in his early years, although probably not to the extent portrayed in the local mythology.

Henry Clifford | |

|---|---|

| 10th Baron Clifford | |

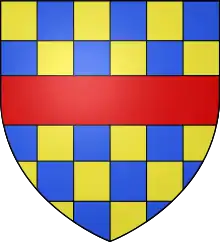

Arms of Clifford, Chequy or and azure a fess gules | |

| Predecessor | John Clifford, 9th Baron Clifford |

| Successor | Henry Clifford, 1st Earl of Cumberland |

| Born | c. 1454 |

| Died | 23 April 1523 |

The Yorkist regime came to an end in 1485 with the invasion of Henry Tudor, who defeated Edward's brother, Richard III, at the Battle of Bosworth Field. Henry's victory meant that he needed men to control the North of England for him, and Clifford's career as a loyal Tudor servant began. Soon after Bosworth, the King gave him responsibility for crushing the last remnants of rebellion in the north. Clifford was not always successful in this, and his actions were not always popular. On more than one occasion, he found himself at loggerheads with the city of York, the civic leadership of which was particularly independently minded. When another Yorkist rebellion broke out in 1487, Clifford suffered an embarrassing military defeat by the rebels outside the city walls. Generally, however, royal service was extremely profitable for him: King Henry needed trustworthy men in the region and was willing to build up their authority in order to protect his own.

Although Clifford's later years were devoted to service in the north and fighting the Scots (he took part in the decisive English victory at Flodden in 1513) he fell out with the King on numerous occasions. Clifford was not an easy-going personality; his abrasiveness caused trouble with his neighbours, occasionally breaking out in violent feuds. This was not the behaviour the King expected from his lords. Furthermore, Clifford had married a cousin of the King, yet Clifford's infidelity to her was notorious among his contemporaries. This also drew the King's ire, to the extent that the couple's separation was mooted. Clifford's first wife had died by 1511, and Clifford remarried. This was also a tempestuous match, and on one occasion he and his wife ended up in court accusing each other of adultery. Clifford's relations with his eldest son and heir, the eventual Henry Clifford, 1st Earl of Cumberland, were equally turbulent. Clifford rarely attended the royal court himself, but sent his son to be raised with the King's heir, Prince Arthur. Clifford later complained that young Henry not only lived above his station, he consorted with men of bad influence; Clifford also accused his son of regularly beating up his father's servants on his return to Yorkshire.

Clifford outlived the King and attended the coronation of Henry VIII in 1509. While continuing to serve as the King's man in the north, Clifford carried on his feuds with the local gentry. He also indulged his interests in astronomy, for which he built a small castle for observation purposes. Clifford grew ill in 1522 and died in April of the following year; his widow later remarried. Young Henry inherited the title as 11th Baron Clifford as well as a large fortune and estate, the result of his father's policy of frugality and avoiding the royal court for most of his life.

Background

The Clifford family, originally from Normandy, settled in England after the conquest of 1066. The family was elevated to the peerage in 1299 as Barons Clifford, and also held the minor baronies of Skipton in North Yorkshire[2] and of Appleby in Westmoreland.[3] The historian Chris Given-Wilson has described the Clifford family as one of the greatest 15th-century families never to receive an earldom.[4] By the time of Clifford's birth, the King, Henry VI, was politically weak and occasionally incapacitated, which prevented him from ruling effectively. His failure to control his nobility, combined with the loss of England's French territories during the latter years of the Hundred Years' War had seen the political situation in England deteriorate into what the scholar David Loades has called a "chaos of factional quarrels".[5] Civil war (known to historians as the Wars of the Roses) broke out in 1455. By 1461 a number of battles had been fought between nobles loyal to the Lancastrian King and those of the Yorkists, led by Richard, Duke of York, who had claimed the throne in 1460.[6]

These engagements became increasingly bloody, comments the author Robin Neillands, "either in the actual battle or the subsequent rout".[7] At the Battle of Wakefield in December 1460 Clifford's father supposedly encountered York's second son Edmund, Earl of Rutland, on Wakefield Bridge, as the latter was attempting to flee the destruction of his father's army. John, Lord Clifford, crying "by God's blood, thy father slew mine and so shall I slay thee", stabbed Rutland to death.[8][note 1] Lord Clifford himself died on 28 March the following year during another clash at Ferrybridge, North Yorkshire. Tradition states that he was killed by a headless arrow to the throat and buried, along with those who died with him, in a common burial pit.[10][11]

The next day, the bulk of the Yorkist and Lancastrian armies faced each other at the Battle of Towton. After what is believed to be the biggest and possibly bloodiest battle ever to take place on English soil,[12][13] the Lancastrians were routed, and the son of the Duke of York was crowned King Edward IV.[14] On 4 November 1461, at Edward's first parliament, the dead Lord Clifford was attainted and his estates and barony forfeited to the Crown.[11][15][note 2] The bulk of the Clifford lands were granted to Richard, Earl of Warwick,[1] while Richard, Duke of Gloucester, and Sir William Stanley received the Lordship of Westmorland and the Barony of Skipton respectively.[17] The latter included the Clifford caput baroniae, Skipton Castle.[18]

Family and early life

Henry Clifford was born around 1454,[19] the eldest son and heir of John Clifford and Margaret Bromflete.[20] In the view of the medievalist A. G. Dickens, Margaret, as sole heiress to her father Henry, brought Clifford's father a "questionable claim" to the title Lord Vescy. She also brought Clifford extensive lands in the East Riding.[21]

"Shepherd Lord"

Popular belief later held that as a boy of seven, Clifford was spirited away from his home in Skipton Castle following his father's death. For his own protection, so it went, his mother sent him to live in Londesborough on the property of a trusted family nurse where he employed himself tending the family's sheep. Whenever his mother believed him likely to be discovered he would be moved. Precisely where to is unknown, but both Yorkshire and Cumberland are possible; in the latter case, for example, Clifford's father-in-law held estates in Threlkeld.[22] This supposedly gave Clifford the soubriquet "shepherd lord".[23][24] The story seems to have originated with the 16th-century antiquarian Edward Hall and been reiterated by Lady Anne Clifford, in her 17th-century family history. The early modern historian Jessica Malay, argues that "with Edward IV on the throne (elder brother of the Earl of Rutland) and the Clifford hereditary lands forfeit, the Clifford dynasty was threatened with extinction".[20] Lady Anne was, she says, "keen to emphasise the role of women in the survival of the Clifford dynasty", and as such created a "dramatic narrative" in which Margaret deliberately defies the crown for the sake of her dead husband's heir. Anne clearly believed that King Edward sought revenge for the murder of his younger brother, which put young Clifford's life in danger.[20][note 3] Malay suggests that, while Anne Clifford believed the story of the shepherd's family taking her ancestor in, modern historians generally discount it as folklore, to greater or lesser degrees.[20] It has received some traction; the 19th-century genealogist George Edward Cokayne accepted the story of Clifford's being "(for security against the disfavour with which his family was viewed by the reigning house) concealed by his mother" and raised as a shepherd,[19] as did the antiquarian J. W. Clay in a 1905 article for the Yorkshire Archaeological Journal.[28] The scholar R. T. Spence also repeated the story in his 1959 University of London PhD thesis on the later Cliffords (writing that Clifford was "brought up as a Shepherd boy to escape the fate of his father's victim").[29] Three years later Dickens (in his edition of the Clifford Papers) described how Clifford "aged about seven, lay in real danger and was brought up first as a shepherd".[21][note 4]

The topographer Thomas Dunham Whitaker expressed doubt as to the 'shepherd lord' story's veracity in 1821.[31] More recently, the historian K. B. McFarlane has gone further, arguing that it was probably "apocryphal",[32] and J. R. Lander calls it "very dubious indeed".[33] James Ross has pointed out that Clifford was pardoned by Edward IV in 1472 and could hardly have been in danger from the King thereafter. Further, he notes, as early as 1466[34] Clifford was named publicly as receiving a bequest of a sword and a silver bowl by Henry Harlington of Craven.[1] This argues that the young lord could not have been difficult to find, comments Ross. He also, though, suggests that Clifford may well have kept a low profile after Towton, if only temporarily: "it may not have been with a shepherd, but surely Clifford was in hiding in secret somewhere".[34] Malay also suggests that "in all likelihood, he spent only a few years in rural retreat" in Cumberland.[20] Clifford's biographer Henry Summerson, writing in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, also refutes the theory, "later stories to the contrary notwithstanding, that the seven-year-old Henry Clifford was ever pursued by vengeful Yorkists". Summerson notes, for example, that Hall wrote that Clifford—due to his upbringing by remote shepherds—was illiterate. In reality, says Summerson, Clifford "was later to be not just literate but even bookish, owning volumes on law and medicine". Summerson agrees that "it may be that the Clifford heir thought it prudent to keep a low profile" in the early years of the new regime.[1] While the medievalist Vivienne Rock subscribes to the theory that Clifford grew up ill-educated, she agrees that in later life "he did become an able administrator for his substantial estates".[35][note 5]

Inheritance and estates

Ross described the Clifford estates—centred on Cumberland, Westmorland, Durham and Yorkshire—as "valuable and strategically important in the troubled north".[18] The 9th Baron had never, though, been as wealthy as some of the neighbouring families, such as the Darcys.[37] His 1461 attainder prevented his son from inheriting, but in 1470 King Edward was forced from the throne and into exile, and Henry VI was returned to the throne.[38] The Earl of Warwick—now aligned with the House of Lancaster against Edward—was in charge of the government,[1] and his brother, John, Marquess Montagu, was granted the Henry Clifford's wardship during his minority.[39] Summerson posits that this was a chance for Clifford to regain his inheritance.[1] There was probably insufficient time to press his claim, however, as both Nevilles were killed at the Battle of Barnet on 14 April the following year.[1] Edward IV's victory at Barnet, and at the Battle of Tewkesbury a few weeks later, destroyed the remnants of Lancastrian resistance and returned Edward to the throne. Despite Clifford's Lancastrian connections, he seems never to have been in any danger at this time, as on 16 March 1472 Edward granted him a royal pardon.[1] This was despite an attempt by Clifford's brother Thomas to raise an—albeit unsuccessful—pro-Lancastrian rebellion in Hartlepool.[40] Henry Clifford was duly allowed to inherit the estates of his maternal grandfather, Henry Bromflete, Lord Vescy—who had died in 1469—but not yet his Clifford patrimony.[41] Further, as his mother was still alive, a third of his inheritance—her dower[note 6]—remained out of his control until her death in 1493.[1]

Accession of Henry VII

|

Edward IV died in April 1483 and his son Edward V was intended to succeed to the throne. However, he and his brother were declared illegitimate by their uncle, Richard of Gloucester, who took the throne himself as Richard III. Richard's reign was brief; in 1485 the heir of Lancaster, Henry Tudor, Earl of Richmond invaded England and defeated Richard at the Battle of Bosworth Field on 22 August 1485.[43] Nothing is known of Clifford's career between his pardon in 1472 and the end of the Yorkist regime,[1] except that he had remained in the country.[44] Michael Hicks has suggested that his presence in the north, even though still attainted, made Gloucester's hold on the Clifford lands more fragile than was comfortable for the Duke: "no doubt Gloucester himself could keep what he had, but could his heirs?"[45] Clifford had been one of a number of stalwart[46] Lancastrian lords excluded from local power in the region during Gloucester's hegemony, first as Duke and then King.[47]

Henry Tudor took the throne as Henry VII and from that point Clifford's position swiftly, and radically, improved.[1] He received a number of local offices and sat on commissions in Westmorland and Yorkshire,[48] although he was not to be appointed justice of the peace in the West Riding, until 1497.[49] Following Bosworth, the new King's biggest priority was securing the north, where it was suspected that the Earls of Northumberland and of Westmorland were planning an insurrection. On 18 August[50] Clifford was commissioned to raise a force to crush dissent in the region. He sent the earls to London under arrest and received into the King's grace those who wished to make peace with the new regime ("for all", notes A. J. Pollard, "but a number of named men").[51][52] On 24 October 1486, Clifford wrote to the city of York (at the time, the capital of the north) warning them not to sell arms or armour to non-residents.[52]

Clifford was present at King Henry's first parliament on 15 September 1485,[19] at which time he was legally still attainted.[53] He attended every parliament until 23 November 1514, being summoned as Henrico Clifford de Clifford ch'r.[19] During his first parliament Clifford successfully petitioned for the overturning of his father's attainder, which restored Clifford's patrimony to him.[1] He was knighted on 9 November 1485.[19]

Career in the north

Clifford made a natural ally for King Henry, and soon became one of his most trusted men in the north.[50] Summerson suggests that Henry had little choice in restoring Clifford to his traditional regional position, as Northern England had been firmly Yorkist for over 20 years, first under the Nevilles and then under Gloucester. The latter had made Yorkshire his power base.[1] Clifford, already loyal to Lancaster and then Tudor, was an obvious choice to act as the King's man, and Henry gradually increased Clifford's power. On 2 May 1486[54] Clifford received the stewardship of the Lordship of Middleham and bailiwick of the Honour of Richmond.[1] The former had been one of Richard of Gloucester's most important headquarters.[55] After Richard took the throne, he granted it to Sir John Conyers,[54] one of Gloucester's closest advisers;[56] both Middleham and Richmond had been Neville strongholds before that.[57] Conyers seems to have been placed in Clifford's custody around this time, although relations between the two men seem to have improved: Clifford later jointly shared in a £1,000 bond to the King for Conyers's good behaviour.[58] In October 1486 Clifford sat on a commission to "levy for the King, all profits arising from the King's manors and lands in the counties of Westmorland and Cumberland, the lordship of Penrith and the forest of Inglewood" in expectation of an invasion by Scotland.[59]

The city of York jealously guarded its liberties, and traditionally rejected all interference from the outside unless it was perceived as absolutely warranted.[60] This resistance troubled Clifford throughout his career. During the Yorkist rebellion of 1487, which attempted to place Lambert Simnel on the throne (as a pretender for Edward IV's second son, Richard of Shrewsbury) Clifford was responsible for guarding the city. He reinforced the garrison with 200 of his men at arms;[61] when the rebel army passed close by, Clifford followed it to Braham.[note 7] He attempted to engage it on 10 June, but was beaten off.[62] He camped in Tadcaster overnight,[61] where word was brought to him that a small force of rebels, led by Lords Scrope of Masham and of Bolton[63] had launched an assault on Bootham Bar. This forced Clifford to withdraw back to York and face the rebels[62] on 13 June.[63] The subsequent encounter was not an unqualified success, notes Summerson; Clifford was defeated in a scuffle outside the gates, and lost all his baggage.[1] The military historian Philip A. Haigh writes that Clifford was "utterly disgraced" and R. W. Hoyle describes his efforts as a "fiasco".[37][61] The city scribes "laconically recorded the disastrous outcome", writes Anthony Goodman, and emphasised how the King's man in the north "had signally failed" to contain the rising.[64]

Meanwhile, the King's army under John de Vere, Earl of Oxford, had won a decisive victory over the rebels at the Battle of Stoke 16 June 1487.[65] Clifford was again given responsibility for the safety of York,[66] and he claimed "captenship" over the city, an assertion the city rejected.[67] In 1488 Clifford and Lady Anne both joined the city's Corpus Christi Guild. This does not seem to have restored Clifford in the eyes of the city officialdom, as the following year they again refused him entry, claiming that his intentions threatened the city's liberties. This may well have been prescient, suggests Summerson, as in 1513 Clifford attempted to claim the city's troops for his own army.[1] In 1489 the townspeople, "denyed the entrie of the Lords Clifford and othre, that in nowise noon othre gentilman of what degreor condiconhe he of be suffred to enter this the Kyngs Chaumbre and so all to be excludet and noon to have reule bot the Maiour, Aldermen and the Shireffs".[68] The city's statement came just before rebellion again broke out in Yorkshire, this time against heavy taxes. The commons overran the city and refused to allow Clifford or the sheriff, Marmaduke Constable entry. Instead, the citizens not only allowed the rebels to enter, they provided them a degree of military assistance.[66][note 8] The medievalist David Grummitt comments that the city's reluctance to allow Clifford either office or military assistance is in stark contrast to the fervour with which they served "our ful gode and gracious lorde the duc of Gloucestre" as both Duke and King.[67]

Clifford was in London in 1494 when he and the King's second son, Prince Henry,[69] among others, were made Knights of the Bath.[1] Clifford spent much of the remainder of the decade on service in the north. Although he never held office on the border,[37] he led a major campaign in 1497,[1] besieging and capturing Norham Castle from the Scots.[41] Clifford was probably a member of the Council of the North around the turn of the century. This body was under the nominal leadership of Prince Arthur and managed by the Archbishop of York, Thomas Savage.[1][note 9] Clifford's lordship of the north, posits Summerson, was reciprocal: Henry extended royal power in the region by strengthening Clifford, and likewise, Clifford strengthened and augmented his own position through royal service.[1]

Patronage, alliances and local relations

Clifford, although a figure of political and social influence, only ever had regional interests.[37] His approach to his estates was generally positive, suggests Summerson. Clifford regularly travelled between Westmorland and Yorkshire (visiting manors "where no Clifford had been seen for a quarter of a century") and took the opportunity to rebuild and repair castles and other properties as he did. These he funded with traditional feudal dues, such as offices, wardships and marriages that were within his purview. His determined augmentation of his estates occasionally led to summonses before the royal council for enclosing land.[1] Conversely, Clifford attempted to build good relations with his tenants and neighbours through financial generosity and hospitality, such as in 1521, when he held a "great Christmas" at Brough Castle.[1][note 10]

On occasion, Clifford made the enmity of his neighbours as a direct result of his royal service. For example, it was often to the Crown's advantage that, where possible, it influenced civic elections in favour of royal candidates. A particularly important such office was that of the city recorder. In the early years of Henry's reign the administration of York, as the capital of the north, keenly interested the King. Its regional position, combined with a history of Yorkist loyalism, made it, the scholar James Lee suggests, a "touchstone for loyalty to Henry".[73] The King attempted to impose his own man, but the city council disagreed. Clifford then attempted to intercede for the King, but to no avail, and in the end, a compromise candidate, John Vavasour, was elected.[73] Summerson notes that Clifford's attempts to insert himself into local politics were "not always well-received". Summerson highlights Clifford's declaration in 1486 to the Mayor and Common Council that he intended "to mynistre as myn auncistres haith done here to fore in all thinges that accordith to my dewtie". In response, York's officials "firmly" informed Clifford that he had no such duty as his ancestors had never wielded such authority.[1] Clifford also attempted, unsuccessfully, to influence the civic celebrations the city organised for the King's first visit to York later the same year. He wished, says Lee, to show the King the degree to which he was in control now that he had been returned to his family's traditional position; he was told by Vavasour that the city would do as it saw fit.

In 1487 the Earl of Oxford had been granted the wardship and marriage[74] of the 17-year-old[75] Elizabeth Greystoke, granddaughter and sole heiress of Ralph, Baron Greystoke. Oxford soon sold the rights (worth nearly £300 per annum) to Clifford. Within a short time, though, Elizabeth was taken from Clifford's custody ("without leave asking, and not without peril to his person"[75]) by Thomas, Lord Dacre.[74] By 1491, relations between the two men had deteriorated to the extent that the King personally prosecuted them both in the Star Chamber for rioting; they were each fined £20.[76] King Henry was more likely to have been concerned, in cases such as these, with bending his tenants-in-chief to his political will than the revenue these forfeits added to his Exchequer.[77] Hicks has suggested that this behaviour made Clifford less trustworthy in Henry's eyes as a crown agent.[78] In 1496 the Captain of Carlisle, Henry Wyatt, wrote to the King[79][note 11] expressing, as Agnes Conway calls it, his "poor opinion" of Clifford. Wyatt considered Clifford's wife, Lady Anne St John, to be a more able administrator than her husband, whom he considered inefficient, and told the King so plainly.[81]

Clifford's success at improving his finances eventually placed him in the top third of the English nobility and enabled him to successfully create new connections and strengthen existing ones. This he achieved through both marriage alliances with, and retaining among, the local gentry.[1][note 12] Clifford was also a major patron to local abbeys, monasteries and priories. To Bolton Priory,[1] for example, he donated a manuscript now known as A Treatise of Natural Philosophy in Old French.[84][note 13] Other houses included Gisborough, Mount Grace and Shap; Mount Grace was particularly favoured.[1][note 14] Clifford was a regular correspondent with the heads of other houses, including Byland, Carlisle, Furness, Holmcultram and St. Mary's, York.[87] His extensive patronage did not always bring him success in his political negotiations with them. In 1518, for example, the Dean of York, Brian Higton wrote to Clifford explaining why he had refused to accept Clifford's favoured nominee as parish priest of Conisbrough Church:

Where ye dide of laite presente your clerk unto the church of Conesburgh of your patronege, surely I cane nott (of my conscience) admytte hym to itt, fore his connyng is mervyllus slendure. I haue scyne few prestis so symple lernede in my life. If itt please you to commande some of your lernede chapplens to oppoise hym in your presence, I dowte not butte ye shall perceyue the truth. And fore the lakk of his lernynge (Which is manifesteo) I do putte hym bakk, ande fore noyne oder cause, nor at no mannys desire or motlon.[88]

Later years

In the later years of the 15th century, Clifford was frequently the target of the King's displeasure. He often failed to act as the stabilising force in the north that Henry had intended.[89] A feud with Christopher Moresby, an important member of the local gentry, had started in the 1470s[90] and continued well into Henry's reign.[91][note 15] Another time, Clifford led local resistance to a royal tax. In retaliation, Henry challenged Clifford's hereditary right to the shrievalty of Westmorland with quo warranto proceedings in 1505. Clifford's goods were sequestered until he could show by what authority he held the office, and he also had to provide a number of large obligations for his good behaviour. These included a £1,000 bond in May that year, £200 if he departed the council without permission[89] and £2,000 on condition that he, his servants, tenants and "part-takers"[93] kept the peace with Roger Tempest. Clifford had an ongoing feud[89] with Tempest and had attacked and pulled down Tempest's house in Broughton.[93][94][note 16] Although Clifford's shrieval rights were in the event upheld,[1] the case took over a year to be decided, during which time the profits of the office went to the King. On 14 June 1506 Edmund Dudley delivered Clifford his general pardon. By this time Clifford had paid another £100 in cash ("redie money") to the King and had been pressured for £120 more.[89][note 17]

King Henry died on 21 April 1509, and Clifford attended his funeral in Westminster.[1] He stayed to attend the coronation of King Henry VIII on 23 June, when he was made a knight banneret.[19] Shortly after, Dudley—by then imprisoned in the Tower of London on charges of constructive treason—petitioned Henry VIII over what he believed were grave injustices carried out by the King's father against members of his nobility, including Clifford.[99][note 18] The period Clifford spent in the south was one of the few occasions in Clifford's life where he spent a lengthy period away from his northern heartlands. According to Cokayne—possibly citing an unnamed contemporary—Clifford "seldom 'came to court, or London'", spending much of his time in Barden Tower, Bolton,[19] from where most of his extant charters and letters are signed.[41]

War with Scotland and France

War with Scotland broke out again in 1513 when the Scottish King, James IV, declared war on England. James intended to honour the Auld Alliance with France by diverting Henry VIII's English troops from their campaign against the French, against whom England was a member of the Catholic League in the War of the League of Cambrai, supporting the Pope. Henry VIII had also opened old wounds by claiming to be the overlord of Scotland, further angering the Scots.[100] The first—and as it turned out, the only—engagement of the Scottish campaign was fought at Flodden on 9 September.[41] Clifford brought 207 archers and 116 billmen from Yorkshire under his banner of the Red Wyvern[101] and commanded the vanguard.[41] King James was killed in battle, and Clifford captured three Scottish cannons which he took to "decorate" Skipton Castle; the contemporary Ballad of Flodden Field refers to "Lord Clifford with his clapping guns".[100]

In 1521, the Emperor Charles V resumed war with Francis I. King Henry offered to mediate, but this achieved little and by the end of the year England and the Empire were aligned together against France.[102] Clifford provided 1,000 marks[note 19] towards funding the campaign,[19] one of the highest sums the crown received.[41]

Personal life

Marriages, children and family problems

Clifford is known to have married twice. Possibly at the end of 1486[1]—and certainly by 1493[104]—he had wed Anne St. John of Bletsoe Castle.[note 20] She was the daughter of Sir John St John and Alice, daughter of Sir Thomas Bradshaigh of Haigh.[19] Anne's grandmother was Margaret Beauchamp, the mother of Margaret Beaufort, making Anne half-cousin to King Henry VII.[105] It is probable that the King and his mother had a hand in arranging Anne's marriage to Clifford.[106] Their relationship does not seem to have been peaceful, and this probably exacerbated the King's disfavour of Clifford.[1] Clifford's marriage problems were in part due to his conspicuous infidelity, which caused sufficient tension between him and Anne that their separation was suggested.[28] Anne's chaplain began negotiating this with the King and Lady Margaret Beaufort, who went as far as to offer Anne and her daughters a position in Margaret's household[106] expressing the wish that Anne "shall come up and attend upon my Lady".[107] In the event, the crisis passed and Clifford and Anne stayed together until her death in 1508.[1] She was buried in Skipton Church.[28]

By July 1511,[1] Clifford had married Florence Pudsey, widow of Thomas Talbot. She was the daughter of Henry Pudsey of Berforth and Margaret Conyers, daughter of Christopher Conyers of Hornby.[19] Clifford and Lady Florence were enjoined to the confraternity of Guisborough Abbey.[1] Their marriage, too, was fraught with difficulties, and Florence sued her husband in York consistory court for the restitution of conjugal rights. In doing so, suggest the scholars Tim Thornton and Katherine Carlton, "she did not perhaps expect her own conduct to be brought into question".[108] Clifford, though, in his turn, accused her of adultery with a member of his household,[1] one Roger Wharton. Wharton, under examination in court, confessed that "I will never denye ffor a man may be in bedd with a woman and yett do noo hurte". Thornton and Carlton continue, "in one simple statement, Wharton shed light upon the sexual mores of the Clifford household".[108] Wharton also accused Clifford of having an extra-marital relationship with one Jane Browne, also of his household.[109]

Clifford had several illegitimate children by a number of mistresses,[1][note 21] including two sons, Thomas and Anthony.[109] They both later received positions within the family, Thomas becoming deputy-governor of Carlisle Castle in 1537,[112] and Anthony being appointed steward of Cowling, Grassington and Sutton. Both were also made master foresters of Craven.[113] Thomas and Anthony may have been illegitimate, but Clifford considered them men of "substance, education and experience [and] gentlemen", and provided for them in his will.[114]

From his first marriage to Anne, he left two sons,[1] his heir Henry, and Thomas.[84][note 22] With Anne, he also had four daughters,[1] and by Florence, another daughter.[28] A number of these married into the Bowes family of Streatlam, Co. Durham.[115][116][117] Clifford's heir and namesake was born around 1493, and was raised at court with the King's son, the future Henry VIII.[note 23] The relationship between father and son appears to have been as turbulent as that between Clifford and his wives, with a relationship "strained to breaking point", suggests Dickens.[119] In 1511, Clifford complained that young Henry was both wild and a wastrel, who dressed flamboyantly in cloth of gold, "more lyk a duke than a pore baron's sonne as hee is".[1] He protested about "the ungodly and ungudely disposition of my son Henrie Clifforde, in such wise as yt was abominable to heare it".[119] Among his complaints was that Henry had threatened Clifford's servants and disobeyed his father. Clifford also alleged that his son had assaulted Clifford's old servant Henry Popely, had damaged and stolen Clifford's possessions and had sought to retain important men from Clifford's "countree" for himself. He had also harmed Clifford's close relations with local religious institutions, said Clifford, by stealing tithes and beating their tenants and servants.[note 24] The King, meanwhile, had ordered Clifford to pay £40 to his son towards his upkeep at court, which Clifford had done. Clifford had urged his son "to forsake the dangerous counsels of certain evilly-disposed young gentlemen".[119] Clifford's exhortations were not wholly successful, as on at least one occasion his son was incarcerated in the Fleet Prison.[120]

Summerson suggests that Clifford was to a degree culpable for his son's behaviour, considering that if he "had ideas above his station, the responsibility was largely his father's, who not only placed him at court but also set about marrying him into the high aristocracy".[1] It is also probable, suggests Dickens, that Clifford's own frugality towards his son's expenses encouraged his heir's behaviour,[120] perhaps combined with irritation at his father's longevity.[1] Furthermore, Dickens asserts, young Henry's sojourn at court forced a great distance between him and his father, which prevented him from learning at first-hand the responsibilities he would at some point be expected to take up in the north. Young Henry also appears to have fallen out with his stepmother Florence.[119] It was intended that he marry Margaret, daughter of George, Earl of Shrewsbury, but she died before the betrothal. In 1512 young Henry married Margaret Percy, daughter of the Earl of Northumberland,[1][note 25] which further augmented the Clifford family's wealth and influence in the northeast.[123]

Personality and interests

Historians have speculated on Clifford's personality. Summerson, for example, suggests that Clifford was often an abrasive individual, particularly to his tenants and regularly caused the very kind of social disorder that he was expected to suppress.[1] Ross has speculated that Clifford's early years, particularly "the impact of Towton ... must have been profoundly shocking and traumatic",[124] while Goodman has suggested that Clifford's solo attack on the 1487 rebels at Brougham indicates a chivalrous streak, as personal bravery was a highly prized quality.[125] Micheal K. Jones and Malcolm G. Underwood have described Clifford as "eccentric", possibly on account of his upbringing.[104]

Clifford is known to have had an interest in astrology, astronomy and alchemy.[41] A major eclipse crossed England in 1502, for which occasion Clifford is supposed to have built Barden Tower as an observatory. The astronomer S. J. Johnson has speculated that it was his witnessing the eclipse that sparked Clifford's interest in the subject, "in which he did greatly delight".[126] It is likely that Clifford's obsession with the skies—which led him to spend most of his time as a recluse in Barden Tower—was the cause of his wife's consistory suit for her conjugal rights.[127] In Barden, says Jones and Underwood, Clifford led a "strange, reclusive existence".[107]

Clifford had religious interests also and in 1515 spent a large sum on a new chapel, which was intended to be as extravagant as possible.[128]

Death

By September 1522 Clifford was described as "feebled with sickness".[1] The Scottish war was ongoing, and it had been planned that Clifford would again lead an army; in the event, he was too ill to do so, and his son took his place.[119] Clifford died on 23 April 1523. His widow, Florence, later remarried to Richard Grey, son of Thomas Grey, Marquis of Dorset;[129] she died in 1558.[1] Clifford was buried in either Bolton Priory or that of Shap.[1] Following his death, inquisition post mortems assessed his annual income at £1332 2s. 4d,[1] and Lady Anne Clifford later reported him rich "in money, chattells, goods and great stocks of land".[29][41] His son Henry—no longer a minor—gained livery of his patrimony on 18 July 1523.[130] He was summoned two years later to parliament and created Earl of Cumberland.[131] The elevation of the Clifford family to the upper peerage, suggests Summerson, "owed much to Henry Clifford [the elder]'s labours to revive the fortunes of his family".[1] Spence explains Clifford's wealth as resulting from "the prudence and economy of a lifetime's residence on his estates",[29] combined with abstinence of court and its expense, except when made unavoidable by summonses to parliament.[41] Spence also notes, though, that the first Earl was to go on to both waste and neglect his estates in favour of extravagant court living.[132]

Cultural depictions

The Romantic poet William Wordsworth wrote two pieces—Song at the Feast at Brougham Castle and White Doe of Rylstone—romanticising Clifford's career.[133] The White Doe, written between 1806 and 1807[22] describes Clifford as being "most happy in the shy recess / of Barden's lowly quietness".[41] Wordsworth depicts various aspects of Clifford's life: the loss of his estates in 1461, his rustic upbringing—and the role his father-in-law, Sir Lancelot Threlkeld played—his post-Bosworth revival and his castle building. Wordsworth also imagines the Christmas celebration at Brough Castle "and the peculiarly Wordsworthian results" of Clifford's early life. The poem, suggests the scholar Curtis Bradford, indicates that Wordsworth "was not entirely uninterested in the antiquarian romanticism so characteristic of his time".[134] Charlotte Mary Yonge compares Clifford in his shepherd hut to the roaming of the deposed King Henry VI—now supposedly a hermit—around the north, and casts them together: "both are in hiding: each is content with his lot. The boy does not dream that the hermit is really a king. That he is a man of God is clear, and young Clifford loves him, for his goodness, and most willingly places himself under Henry's tutelage".[135]

The life and career of Henry Clifford was fictionalised by Isaac Albéniz and Francis Money-Coutts—the former writing the music, the latter the libretto—in their opera Henry Clifford, which premiered in 1895.[136]

Notes

- Shakespeare immortalised the scene in his Henry VI, Part 3, with some adjustments for dramatic effect. Comments the Shakespearean scholar, Peter Saccio, "following the Tudor historians, Shakespeare made Rutland a child at the time of his death. The cruelty of Rutland's slaughter, compounded when Margaret flourished in York's face a handkerchief dipped in Rutland's blood, is an outrage many times recalled by the Yorkist characters in Richard III".[9]

- Post-1461, the Cliffords were one of only seven noble families to remain loyal to the old regime, the others being Exeter, de Vere, Beaumont, Hungerford, Ros and Tudor.[16]

- While John Clifford undoubtedly was responsible for Rutland's death, it was not for many years that it brought Clifford much more than what the medievalist Henry Summerson has called "considerable notoriety". Further expansive lurid details, he says, were "first reported only several decades after the event".[10] He dates the first published description of "Butcher Clifford" as being not until the 1540s, when John Leland published his Itinerary. Leland wrote that "for killing of men at this bataill [Clifford] was caullid the boucher".[25] The annalist William Worcester, writing contemporaneously says that Clifford killed Rutland on Wakefield Bridge as the earl attempted to flee the battle. In the sixteenth century, Worcester's report was expanded by Hall, and this became the source for Shakespeare's account. Various historical inaccuracies were introduced, says Summerson. These included Rutland being aged twelve at the time of his death rather than, as he actually was, seventeen,[10] and also that Clifford beheaded York after the battle, whereas the duke almost certainly fell in the fighting.[26] Lander suggests that most of the later descriptions of Clifford at Wakefield "appear too late to be worthy of much credence".[27]

- Lander notes that this fear of Edward IV's vengeance was not the only example of an exaggerated claim of Yorkist ferocity. Rumours such as these generally originated in the French visitor and writer Philippe de Commines's late 15th-century Mémoires. Other examples from there are the tales of the Duke of Exeter, "barefoot and ragged in the Low Countries begging his bread door to door", and Margaret, Countess of Oxford forced to live on charity and "what she myght get with her nedyll or other such conyng as she excercysed".[30]

- Ross argues that, notwithstanding Summerson's hypothesis, "it would seem strange that, if Clifford's whereabouts were known, he was not taken into custody. He was a potential focus for Lancastrian resistance, his lands were valuable, and securing his person would give those in possession [Warwick and Gloucester] rather greater security of title".[36]

- The legal concept of dower had existed since the late twelfth century as a means of protecting a woman from being left landless if her husband died first. He would, when they married, assign certain estates to her—a dos nominata, or dower—usually a third of everything he was seised of. By the fifteenth century, the widow was deemed entitled to her dower.[42]

- While Clifford was tailing the rebels, the Earl of Northumberland brought his own "great host" to the city.[61]

- This situation would continue into the career of Clifford's son, the Earl of Cumberland, during the 1540s, which was a period of much military activity and therefore one which Clifford made frequent demands on York which were equally as frequently rejected by that city.[67]

- Arthur died in Ludlow on 2 April 1502, following which, says the encyclopedist John A. Wagner, "the northern council existed not as an official organ of government, but as a series of temporary expedients of varying forms".[70]

- Brough Castle burned down shortly afterwards,[71] following which Clifford seems to have made Brougham Castle, near Penrith, his main residence.[72]

- The letter, of 4 June 1496, survives in the Wyatt family muniments as Wyatt MSS.13, and is reprinted in full in Conway's Henry VII's Relations with Scotland and Ireland 1485–1498.[80]

- Retaining was the predominant method by which the nobility attempted to control their areas of influence, and the country gentry, as the most numerous political class in any area,[82] were "the natural allies of the peerage", argues the medievalist Chris Given-Wilson. He suggests that, by this period, "most peers probably had at least a score of knights and esquires in their full-time retinues, while earls frequently had fifty or more".[83]

- The manuscript was returned to the Cliffords following the priory's dissolution in 1539.[85]

- Correspeondence exists between the prior, John Wilson and Clifford; for example, on 13 December 1522, Wilson wrote to Clifford informing him that because of the patronage of a London merchant, the priory now possessed a new guest house: "wee have a proper lodging at our place wich a marchand of London did buld and he is now departed from hus and made knight at the roddes".[86] Grace Mount underwent much rebuilding in the early 16th-century, and this was a frequent topic of Wilson's in his letters to Clifford.[87]

- Which feud Clifford's younger brother Robert joined in, assaulting Moresby's Irthington manor in autumn 1487[92]

- Lander describes the King's treatment of Clifford during this episode as "brutal", but highlights it—along with similarly heavy bonds from other nobles—as part of Henry VII's new regime in bringing recalcitrant nobles to heel.[95]

- Clifford's under-sheriff, Roger Bellingham, was also forced to defend his office in court, and had to pay recognizances of £200 in return for a pardon.[96] Clifford's role was predominantly ceremonial; the undersheriff—appointed by Clifford only if they were acceptable to the King[97]—usually performed the bulk of the work of the office.[98]

- Dudley claimed these individuals had been charged with ruinous fines for the purposes of mulctation and believed, according to T. N. Pugh, that it was "an urgent matter of religious duty, lest the salvation of the deceased monarch's soul should be imperilled and his ascent to heaven be impeded, because he had failed to do right and justice to many of his subjects".[99]

- A medieval English mark was a unit of currency equivalent to two-thirds of a pound.[103]

- Says Dickens, "famed alike for tapestry-making and piety".[84]

- Little is known of these children. The major source for the country's gentry families in the mid-16th century is the extant records of the Heraldic visitations, a form of genealogical census of gentry pedigrees.[110] Whereas children were rarely excluded from the record on account of illegitimacy, there is no mention of either Clifford's nor his son's such offspring in the Yorkshire visitation of 1563–64.[111]

- Thomas spent much of his career on royal service in the north for Henry VIII, for which he was knighted; his offices included governor of Berwick Castle.[84]

- Possibly he was raised by Margaret Beaufort, who occasionally had charge of Henry and other royal wards.[118]

- Although the date of Clifford's letter to the council is unknown, Dickens has proposed a date of around 1517, because that year Thomas Leeke, then incarcerated in the Fleet Prison, wrote to his brother Sir John on 25 October that year and reported that Henry Clifford the younger and Sir George Darcy had until recently been imprisoned with him;[120] Clifford was reported, after two-week's imprisonment, as looking "waxen a sad gentleman".[121] Dickens speculated that Darcy was one of the "ill-disposed gentlemen" whom Clifford warned his son against.[120]

- A lavish description of the wedding festivities is contained in a British Library manuscript (BL Royal 18.D.II), written by William Peeris—priest-secretary to Henry Percy, Earl of Northumberland—as part of a chronicle of the Earl's family.[122]

References

- Summerson 2004a.

- Sanders 1960, p. 143.

- Sanders 1960, p. 140.

- Given-Wilson 1996, p. 64.

- Loades 1988, p. 11.

- Carpenter 1997, pp. 253–254.

- Neillands 1992, p. 93.

- Neillands 1992, p. 98.

- Saccio 1977, p. 160.

- Summerson 2004b.

- Cokayne 1913, pp. 293–294.

- Boardman 1996, p. ix.

- Breverton 2014, p. 131.

- Penn 2013, p. 2.

- Jacob 1993, p. 539.

- Lander 1976, p. 24 +n.128.

- Cokayne 1913, p. 294 n.a.

- Ross 2015, p. 137.

- Cokayne 1913, p. 294.

- Malay 2018, p. 410.

- Dickens 1962, p. 18.

- Bradford 1938, p. 60.

- Hall 1965, p. 255.

- Coleridge 1836, p. 249.

- Leland 1907, p. 40.

- Cokayne 1913, p. 293.

- Lander 1961, p. 134 n.55.

- Clay 1905, p. 372.

- Spence 1959, p. 8.

- Lander 1976, p. 141.

- Spence 1994, p. 1.

- McFarlane 1981, p. 243.

- Lander 1976, p. 140.

- Ross 2015, pp. 138, 139.

- Rock 2003, p. 199 n.20.

- Ross 2015, p. 138.

- Hoyle 1986, p. 64.

- Ross 1975, pp. 152–153.

- Arnold 1984, p. 136 n.55.

- Pollard 2000, p. 301.

- Dickens 1962, p. 19.

- Kenny 2003, pp. 59–60.

- Ross 1981, chapters IV and XI.

- Hicks 1984, p. 29 n.19.

- Hicks 1986a, p. 29.

- Carpenter 1997, p. 224.

- Pollard 1990, p. 2337.

- Lander 1989, p. 28.

- Arnold 1984, p. 129.

- Cunningham 1996, p. 58.

- Pollard 2000, p. 352.

- Pollard 1990, p. 370.

- Powell & Wallis 1968, p. 530.

- Cunningham 1996, p. 55.

- Ross 1981, p. 53.

- Ross 1981, p. 50.

- Ward 2016, p. 15.

- Cunningham 1996, p. 57.

- Yorath 2016, p. 183.

- Murphy 2006, p. 245.

- Haigh 1997, p. 173.

- Pollard 1990, p. 377.

- Dockray 1986, p. 218.

- Goodman 1996, pp. 103–104.

- Ross 2011, p. 118.

- Dockray 1986, p. 222.

- Grummitt 2008, p. 136.

- Hicks 1986b, p. 56.

- Dickens 1962, p. 1.

- Ives 2007, p. 1.

- Pettifer 2002, p. 266.

- Summerson, Trueman & Harrison 1998, pp. 30–32.

- Lee 2003, p. 173.

- Ross 2011, p. 101 + n.56.

- Fraser 1971, p. 220.

- Pollard 1990, p. 391.

- Condon 1979, p. 133.

- Hicks 1978, p. 79.

- Conway 1932, pp. 100, 102.

- Conway 1932, pp. 236–239.

- Conway 1932, p. 102.

- Holford 2010, p. 420.

- Given-Wilson 1996, pp. 79–80.

- Dickens 1962, p. 20.

- Smith 2008, p. 385.

- Coppack 2008, p. 176.

- Scrope & Skeat 1957, p. 4.

- Scrope & Skeat 1957, p. 6.

- Harrison 1972, p. 94.

- Dobson1996, p. 159.

- Yorath2016, p. 178.

- Yorath 2016, p. 186.

- Lander 1976, p. 283.

- Lockyer & Thrush 2014, p. 105.

- Lander 1980, p. 357.

- Harrison 1972, p. 95.

- Clark 1995, p. 129.

- Jewell 1972, p. 191.

- Pugh 1992, p. 88.

- Reese 2003, p. 112.

- Sadler 2006, p. 50.

- Loades 2009, p. 69.

- Harding 2002, p. xiv.

- Jones & Underwood 1992, p. 163.

- Cokayne 1913, p. 294 n.d.

- Rock 2003, p. 198.

- Jones & Underwood 1992, p. 164.

- Thornton & Carlton 2019, p. 80.

- Thornton & Carlton 2019, p. 94 n.4.

- Ailes 2009, pp. 18–21.

- Thornton & Carlton 2019, p. 43.

- Dickens 1962, p. 22 n.29.

- Thornton & Carlton 2019, p. 125.

- Hainsworth 1992, p. 23.

- Hampton 1985, p. 17.

- Hutchinson 1794, p. 254.

- Brown 2015, p. 119.

- Harris 1986, p. 34.

- Dickens 1962, p. 21.

- Dickens 1962, p. 22.

- Walker 1992, p. 123.

- Tscherpel 2003, pp. 98–99 + n.40.

- Malay 2017, p. 217.

- Ross 2015, pp. 138, 140.

- Goodman 1996, p. 103.

- Johnson 1905, p. 175.

- Rock 2003, p. 199.

- Mertes 1988, p. 140.

- Cokayne 1913, pp. 294–295.

- Dickens 1962, p. 22 n.32.

- Cokayne 1913, p. 295.

- Spence 1959, p. 9.

- Cokayne 1913, p. 294 n.e.

- Bradford 1938, p. 61.

- Bearne 1906, p. 14.

- Clark 2002, pp. 113–114.

Bibliography

- Ailes, A. (2009), "The Development of the Heralds' Visitations in England and Wales 1450–1600", Coat of Arms, 3rd ser., V: 7–23, OCLC 866201735

- Arnold, C. E. (1984), "The Commission of the Peace for the West Riding ofYorkshire, 1437–1509", in Pollard, A. J. (ed.), Property and Politics: Essays in Later Medieval English History, Gloucester: Sutton, pp. 116–138, ISBN 978-0-86299-163-0

- Bearne, D. (1906), "Concerning Shepherds", The Irish Monthly, 34: 11–16, OCLC 472424571

- Boardman, A. W. (1996), The Battle of Towton (repr. ed.), Gloucester: Alan Sutton, ISBN 978-0-75091-245-7

- Bradford, C. B. (1938), "Wordsworth's "White Doe of Rylstone" and Related Poems", Modern Philology, 36: 59–70, doi:10.1086/388348, OCLC 937348123, S2CID 161862245

- Breverton, T. (2014), Jasper Tudor: Dynasty Maker, Stroud: Amberley Publishing Limited, ISBN 978-1-44563-402-9

- Brown, A. T. (2015), Rural Society and Economic Change in County Durham: Recession and Recovery, c. 1400–1640, Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer, ISBN 978-1-78327-075-0

- Carpenter, C. (1997), The Wars of the Roses: Politics and the Constitution in England, c. 1437–1509, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-52131-874-7

- Clark, W. A. (2002), Isaac Albéniz: Portrait of a Romantic, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19925-052-3

- Clark, L. (1995), "Magnates and their Affinities in the Parliaments of 1386–1421", in Britnell, R. H.; Pollard, A. J. (eds.), The McFarlane Legacy: Studies in Late Medieval Politics and Society, Stroud: Alan Sutton, pp. 127–154, ISBN 978-0-75090-626-5

- Clay, J. W. (1905), "The Clifford Family", Yorkshire Archaeological Journal, 18: 355–411, OCLC 1034295219

- Cokayne, G. E. (1913), Gibb, V.; Doubleday, H. A.; White, G. H. & de Walden, H. (eds.), The Complete Peerage of England, Scotland, Ireland, Great Britain and the United Kingdom: Extant, Extinct, or Dormant, vol. III: Canonteign–Cutts (14 volumes, 1910–1959, 2nd ed.), London: St Catherine Press, OCLC 163409569

- Coleridge, H. (1836), The Worthies of Yorkshire and Lancashire: Being Lives of the Most Distinguished Persons that Have Been Born In, or Connected with Those Provinces, London: Frederick Warne, OCLC 931177316

- Condon, M. (1979), "Ruling Elites in the Reign of Henry VII", in Ross, C. (ed.), Patronage, Pedigree and Power in Later Medieval England, Gloucester: Alan Sutton, pp. 109–142, ISBN 978-0-84766-205-0

- Conway, A. E. (1932), Henry VII's Relations with Scotland and Ireland 1485-1498, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, OCLC 876303485

- Coppack, G. (2008), "'Make Straight in the Desert a Highway for Our God': The Carthusians and Community in Late Medieval England", in Burton, J.; Stöber, K. (eds.), Monasteries and Society in the British Isles in the Later Middle Ages (new ed.), Woodbridge: Boydell and Brewer, pp. 168–180, ISBN 978-1-84383-386-4

- Cunningham, S. (1996), "Henry VII and Rebellion in North-Eastern England, 1485–1492: Bonds of Allegiance and the Establishment of Tudor Authority", Northern History, 32: 42–74, doi:10.1179/007817296790175182, OCLC 1001980641

- Dickens, A. G. (1962), Clifford Letters of the Sixteenth Century, Durham: Surtees Society, OCLC 230081563

- Dobson, R. B. (1996), Church and Society in the Medieval North of England, London: Bloomsbury, ISBN 978-1-44115-912-0

- Dockray, K. (1986), "The Political Legacy of Richard III in Northern England", in Griffiths, R. A.; Sherborne, J. W. (eds.), Kings and Nobles in the Later Middle Ages: A Tribute to Charles Ross, New York: St. Martin's Press, pp. 205–227, ISBN 978-0-31200-080-6

- Fraser, G. M. (1971), The Steel Bonnets, London: HarperCollins, ISBN 978-0-00747-428-8

- Given-Wilson, C. (1996), The English Nobility in the Late Middle Ages: The Fourteenth-century Political Community (2nd ed.), London: Routledge, ISBN 978-0-41514-883-2

- Goodman, A. (1996), The Wars of the Roses (2nd ed.), New York: Barnes and Noble, ISBN 978-0-88029-484-3

- Grummitt, D. (2008), "War and Society in the North of England, c. 1477–1559: The Cases of York, Hull and Beverley", Northern History, 45: 125–140, doi:10.1179/174587008X256665, OCLC 1001980641, S2CID 159720909

- Haigh, P. A. (1997), Military Campaigns of the Wars of the Roses, Stroud: Sutton, ISBN 978-0-93828-990-6

- Hainsworth, D. R. (1992), Stewards, Lords and People: The Estate Steward and his World in Later Stuart England, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-52105-976-3

- Hall, E. (1965), AMS Press (ed.), Hall's Chronicle (repr. ed.), London: AMS Press, OCLC 505756893

- Hampton, W. E. (1985), "John Hoton of Hunwick and Tudhoe", The Ricardian, 7: 2–17, OCLC 1006085142

- Harding, V. (2002), The Dead and the Living in Paris and London, 1500–1670, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-52181-126-2

- Harris, B. J. (1986), Edward Stafford, Third Duke of Buckingham, 1478–1521, Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, ISBN 978-0-80471-316-0

- Harrison, C. J. (1972), "The Petition of Edmund Dudley", The English Historical Review, 87: 82–89, doi:10.1093/ehr/LXXXVII.CCCXLII.82, OCLC 2207424

- Hicks, M. A. (1978), "Dynastic Change and Northern Society: The Career of the Fourth Earl of Northumberland, 1470–89", Northern History, 14: 78–107, doi:10.1179/nhi.1978.14.1.78, OCLC 1001980641

- Hicks, M. A. (1984), "Attainder, Resumption and Coercion, 1461–1529", Parliamentary History, III: 15–31, OCLC 646552390

- Hicks, M. A. (1986a), Richard III as Duke of Gloucester: A Study in Character, York: Borthwick Publications, ISBN 978-0-90070-162-7

- Hicks, M. A. (1986b), "The Yorkshire Rebellion of 1489 Reconsidered", Northern History, 22: 39–62, doi:10.1179/007817286790616444, OCLC 1001980641

- Holford, M. L. (2010), Border Liberties and Loyalties, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, ISBN 978-0-74863-217-6

- Hoyle, R. W. (1986), "The First Earl of Cumberland: A Reputation Reassessed", Northern History, 22: 63–94, doi:10.1179/007817286790616570, OCLC 1001980641

- Hutchinson, W. (1794), The History and Antiquities of the County Palatine of Durham, vol. III, Newcastle: S. Hodgson & Robinsons, OCLC 614697572

- Ives, E. (2007), Henry VIII, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19921-759-5

- Jacob, E. F. (1993), The Fifteenth Century, 1399–1485 (repr. ed.), Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19285-286-1

- Jewell, H. M. (1972), English Local Administration in the Middle Ages, Newton Abbot: David and Charles, ISBN 978-0-06493-330-8

- Johnson, S. J. (1905), "Annular Eclipses", The Observatory, 28: 173–175, OCLC 60620222

- Jones, M. K.; Underwood, M. G. (1992), The King's Mother: Lady Margaret Beaufort, Countess of Richmond and Derby, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-4-4794-2

- Kenny, G. (2003), "The Power of Dower: The Importance of Dower in the Lives of Medieval Women in Ireland", in Meek, C.; Lawless, C. (eds.), Studies on Medieval and Early Modern Women: Pawns Or Players?, Dublin: Four Courts, pp. 59–74, ISBN 978-1-85182-775-6

- Lander, J. R. (1961), "Attainder and Forfeiture, 1453–1509", The Historical Journal, 4 (2): 119–151, doi:10.1017/S0018246X0002313X, OCLC 863011771, S2CID 160000077

- Lander, J. R. (1976), Crown and Nobility, 1450–1509, London: Edward Arnold, ISBN 978-0-77359-317-6

- Lander, J. R. (1980), Government and Community: England, 1450–1509, London: Edward Arnold, ISBN 978-0-67435-794-5

- Lander, J. R. (1989), English Justices of the Peace, 1461–1509, Gloucester: Alan Sutton, ISBN 978-0-86299-488-4

- Lee, J. (2003), "Urban Recorders and the Crown in Late Medieval England", in Clark, L. (ed.), Conflicts, Consequences and the Crown in the Late Middle Ages, The Fifteenth Century, vol. VII, Woodbridge: Boydell Press, pp. 163–177, ISBN 978-1-84383-333-8

- Leland, J. (1907), The Itinerary of John Leland in England and Wales, vol. I–III (repr. ed.), London: George Bell, OCLC 852065768

- Loades, D. M. (1988), Politics and Nation: England 1450–1660 (3rd ed.), London: Fontana, ISBN 978-0-00686-013-6

- Loades, D. (2009), Henry VIII: Court, Church and Conflict, Kew: The National Archives, ISBN 978-1-90561-542-1

- Lockyer, R.; Thrush, A., eds. (2014), Henry VII, Seminar Studies in History (3rd ed.), London: Routledge, ISBN 978-1-31789-432-2

- Malay, J. L. (2017), "Crossing Generations: Female Alliances and Dynastic Power in Anne Clifford's Great Books of Record", in Lucky, J. C.; O'Leary, N. J. (eds.), The Politics of Female Alliance in Early Modern England, Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, pp. 207–224, ISBN 978-1-49620-199-7

- Malay, J. L. (2018), "Lady Anne Clifford's Great Books of Record: Remembrances of a Dynasty", in Phillippy P. (ed.), A History of Early Modern Women's Writing, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 398–416, ISBN 978-1-10857-628-4

- McFarlane, K. B. (1981), England in the Fifteenth Century, London: Hambledon Press, ISBN 978-0-90762-801-9

- Mertes, K. (1988), The English Noble Household, 1250–1600: Good Governance and Politic Rule, Oxford: Basil Blackwell, ISBN 978-0-63115-319-1

- Murphy, N. (2006), "Receiving Royals in Later Medieval York: Civic Ceremony and the Municipal Elite, 1478–1503", Northern History, 45 (2): 241–255, doi:10.1179/174587006X116167, OCLC 1001980641, S2CID 159965976

- Neillands, R. (1992), The Wars of the Roses, London: Cassell, ISBN 978-1-78022-595-1

- Penn, T. (2013), Winter King: Henry VII and the Dawn of Tudor England, London: Simon and Schuster, ISBN 978-1-43919-157-6

- Pettifer, A. (2002), English Castles: A Guide by Counties, Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer, ISBN 978-0-85115-782-5

- Pollard, A. J. (1990), North-Eastern England during the Wars of the Roses: Lay Society, War, and Politics 1450–1500, Oxford: Clarendon Press, ISBN 978-0-19820-087-1

- Pollard, A. J. (2000), Late Medieval England, 1399–1509, London: Longman, ISBN 978-0-58203-135-7

- Powell, J. Enoch; Wallis, K. (1968), The House of Lords in the Middle Ages, London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, ISBN 9780297761051, OCLC 905631479

- Pugh, T. B. (1992), "Henry VII and the English Nobility", in Bernard, G. W. (ed.), The Tudor Nobility, Manchester: Manchester University Press, pp. 49–110, ISBN 978-0-71903-625-5

- Reese, P. (2003), Flodden: A Scottish Tragedy, Edinburgh: Birlinn, ISBN 978-0-85790-582-6

- Rock, V. (2003), "Shadow Royals? The Political Use of the Extended Family of Lady Margaret Beaufort", in Eales, E.; Tyas, S. (eds.), Family and Dynasty in Late Medieval England, Proceedings of the 1997 Harlaxton Symposium, vol. IX, Donington: Shaun Tyas, pp. 193–210, ISBN 978-1-90028-954-2

- Ross, C. D. (1975), Edward IV, Berkeley: University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-52002-781-7

- Ross, C. D. (1981), Richard III, Berkeley: University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-52005-075-4

- Ross, J. A. (2011), The Foremost Man of the Kingdom: John de Vere, Thirteenth Earl of Oxford (1442–1513), Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer, ISBN 978-1-78327-005-7

- Ross, J. A. (2015), "The Treatment of Traitors' Children and Edward IV's Clemency in the 1460s", in Clark, L. (ed.), Essays Presented to Michael Hicks, The Fifteenth Century, vol. XIV, Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer, pp. 131–142, ISBN 978-1-78327-048-4

- Saccio, P. (1977), Shakespeare's English Kings: History, Chronicle, and Drama, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19502-156-1

- Sadler, J. (2006), Flodden 1513: Scotland's Greatest Defeat, Oxford: Osprey, ISBN 978-1-84176-959-2

- Sanders, I. V. (1960), English Baronies: A Study of Their Origin and Descent, 1086–1327, Oxford: Clarendon Press, OCLC 2437348

- Scrope, K.; Skeat, T. C. (1957), "Letters from the Reign of Henry VIII", The British Museum Quarterly, 21 (1): 4–8, doi:10.2307/4422548, JSTOR 4422548, OCLC 810961271

- Smith, D. M. (2008), The Heads of Religious Houses: England and Wales: 1377–1540, vol. III, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-52186-508-1

- Spence, R. T. (1959), The Cliffords, Earls of Cumberland, 1579–1646: A Study of their Fortunes based on their Household and Estate Accounts (PhD thesis), University of London, OCLC 1124256460

- Spence, R. T. (1994), The Shepherd Lord of Skipton Castle: Henry Clifford 10th Lord Clifford 1454–1523, Skipton: Skipton Castle, ISBN 978-0-95069-752-9

- Summerson, H.; Trueman, M.; Harrison, S. (1998), "Brougham Castle, Cumbria", Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society Research Series, Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society (8), ISBN 978-1-8731-2425-3

- Summerson, H. (2004a), "Clifford, Henry, Tenth Baron Clifford (1454–1523)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.), Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/5646, archived from the original on 3 November 2019, retrieved 3 November 2019 (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Summerson, H. (2004b), "Clifford, Henry, Ninth Baron Clifford (1435–1461)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.), Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/5654, archived from the original on 3 November 2019, retrieved 3 November 2019 (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Thornton, T.; Carlton, K. (2019), The Gentleman's Mistress: Illegitimate Relationships and Children, 1450–1640, Manchester: Manchester University Press, ISBN 978-1-52611-409-9

- Tscherpel, G. (2003), "The Political Function of History: The Past and Future of Noble Families", in Eales, E.; Tyas, S. (eds.), Family and Dynasty in Late Medieval England, Proceedings of the 1997 Harlaxton Symposium, vol. IX, Donington: Shaun Tyas, pp. 87–104, ISBN 978-1-90028-954-2

- Walker, G. (1992), "John Skelton, Cardinal Wolsey and the Tudor Nobility", in Bernard, G. W. (ed.), The Tudor Nobility, Manchester: Manchester University Press, pp. 111–133, ISBN 978-0-71903-625-5

- Ward, M. (2016), The Livery Collar in Late Medieval England and Wales: Politics, Identity and Affinity, Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer, ISBN 978-1-78327-115-3

- Yorath, D. M. (2016), "Sir Christopher Moresby of Scaleby and Windermere, c. 1441–99", Northern History, 53 (2): 173–188, doi:10.1080/0078172X.2016.1178941, OCLC 1001980641, S2CID 164109969