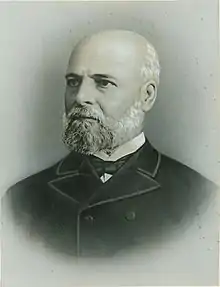

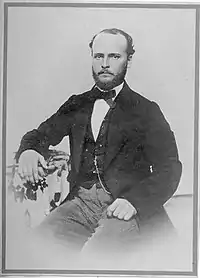

Henrique Dumont

Henrique Honoré Dumont[1] (July 20, 1832 in Diamantina – August 30, 1892 in Rio de Janeiro) was a Brazilian engineer[2] and coffee farmer, and the father of Alberto Santos-Dumont. A son of French immigrants, he is considered one of the three Coffee Kings of his time, introducing modern methods to coffee farming.[3]

Henrique Dumont Henri Dumont | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Henrique Honoré Dumont[1] July 20, 1832 Diamantina, Minas Gerais, Empire of Brazil |

| Died | August 30, 1892 (aged 60) |

| Nationality | Brazilian |

| Other names | Coffee King |

| Alma mater | École Centrale Paris |

| Occupation | Coffee farmer |

| Known for | Owning large crops and coffee farms |

Biography

Henrique Dumont's parents came from France. His mother, Eufásia Honoré, the daughter of a goldsmith, married his father, François Dumont. Eufásia's father convinced François to move to Brazil in search of precious stones, which would feed his industry. But after the discovery of diamonds in South Africa, prices fell, and François fell ill and died in 1842.[1] In Brazil the couple had three children, the second being Henrique.[4]

Helped by his godfather, he graduated as an engineer from the École centrale des arts et manufactures in Paris at the age of 21. Dumont returned to Brazil and began to render services to the city of Ouro Preto. Dumont and his wife Francisca Santos, daughter of Francisco da Paula Santos, were married on September 6, 1856, in the Parish of Nossa Senhora do Pilar, in Ouro Preto.[4][1]

In 1871, Henrique, under contract with Joaquim Saldanha Marinho, built a steamboat, launched into the São Francisco River by Emperor Dom Pedro II.[1]

In 1872, during the reign of Pedro II, Dumont was commissioned to construct a section of the Central Railroad of Brazil in Minas Gerais, on the ascent of the Mantiqueira Mountains. With the construction site fixed in the locality of Cabangu, the family settled in a nearby farm; here, on July 20, 1873 (Henrique's 41st birthday), his son, Alberto Santos Dumont, was born.[5][1]

When the railroad was completed, Henrique Dumont decided to dedicate himself to the cultivation of coffee. He left Minas Gerais and went to the municipality of Valença, in Rio de Janeiro; in this region, his son Alberto was baptized in 1877 in the parish of Santa Tereza, current municipality of Rio das Flores.[4][1]

Searching for more suitable land for coffee growing, Dumont moved to Ribeirão Preto, in São Paulo, and settled in the Fazenda Arindeuva.[6] He then owned a little more than 300 contos e réis and 80 slaves,[7] with 150 being rented. However, due to an apparent fear of revolts, he began to adopt the labor of colonists even before the abolition of slavery in Brazil.[8] By applying his knowledge of engineering, Dumont was able to stimulate production at his new farm through a series of innovations, making it into the most modern farm in South America, with five million coffee trees, 96 kilometers of railroads and seven locomotives.[9]

In 1883, an extension of the Mogiana Railroad to Ribeirão Preto was inaugurated, obtained by demand of Henrique Dumont ; this extension was fundamental for the flow of production and for the development of the region, bringing hundreds of immigrants, mainly Italians, who soon replaced the slave labor force.[4][10] In 1857 Henrique formed the largest coffee farm in Brazil, with 5.7 million plants and on October 10, 1888 Henrique signed a contract to connect his farm to the railroad, building 100 km of tracks.[1]

Last years

In December 1890, Dumont fell from a cart on one of his farms breaking his arm and hitting his head, leaving him hemiplegic.[1] Later, in 1891, as a result of the treatment, he sold his farms for 12 million réis ($5 million in 1895) and left for Europe with his family.[11][12] In France he sought the best medical treatment, but returned to Brazil on November 21, 1891 with a 2.5 HP Peugeot, the first gasoline-powered car in Brazil.[1]

In 1891, shortly before his death, Henrique emancipated his minor children and gave each one his share in the inheritance. To his son Alberto Santos Dumont, in February 12, 1892, he said " I prefer you not to become a doctor; the future of the world is in mechanics.".[2][13][1] He tried to return to France due to his deteriorating health, but died on August 30 of 1892, at the age of 60, in the city of Rio de Janeiro..[1]

References

- Demartini Jr, Zeferino; Gatto, Luana A. Maranha; Lages, Roberto Oliver; Koppe, Gelson Luis (2019). "Henrique Dumont: how a traumatic brain injury contributed to the development of the airplane". Arquivos de Neuro-Psiquiatria. FapUNIFESP (SciELO). 77 (1): 60–62. doi:10.1590/0004-282x20180149. ISSN 1678-4227. PMID 30758444.

- "Santos Dumont: As Asas do Homem" [Santos Dumont: The Wings of Man]. Archived from the original on July 13, 2019. Retrieved December 15, 2017.

- "Ruas do Rio IX". Archived from the original on September 12, 2014. Retrieved February 23, 2010.

- "ALBERTO SANTOS DUMONT". Archived from the original on December 16, 2017. Retrieved December 15, 2017.

- "História de Alberto Santos Dumont" [History of Alberto Santos Dumont]. Archived from the original on December 15, 2017. Retrieved December 15, 2017.

- Henrique Lins de Barros (2016). Santos-Dumont and the Invention of the Airplane (PDF). Translated by Maria Cristina Ramalho Ardoy. CBPF. p. 9. ISBN 978-85-85752-17-0. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 27, 2021.

- Morel, Edmar (September 25, 1974). "Vida e Morte do Pai da Aviação (I)". O Cruzeiro (in Brazilian Portuguese). Vol. 46, no. 37. p. 63.

- Oliveira 2022, p. 243.

- Paul Hoffman (June 16, 2004). Wings of Madness: Alberto-Santos Dumont and the Invention of Flight. Hyperion Books (published 2003). p. 13. ISBN 0-7868-8571-8.

- "Lembranças do 'Tio Alberto'" [Memories of 'Uncle Alberto']. Archived from the original on July 11, 2019. Retrieved July 11, 2019.

- "História da Indústria e a Tecnologia Aeronáutica" [History of Industry and Aeronautical Technology] (in Brazilian Portuguese). Archived from the original on April 9, 2016. Retrieved February 23, 2010.

- Oliveira 2022, p. 244.

- O que eu vi, o que nós veremos

Further reading

- Demartini Jr, Zeferino; Gatto, Luana A. Maranha; Lages, Roberto Oliver; Koppe, Gelson Luis (2019). "Henrique Dumont: how a traumatic brain injury contributed to the development of the airplane". Arquivos de Neuro-Psiquiatria. FapUNIFESP (SciELO). 77 (1): 60–62. doi:10.1590/0004-282x20180149. ISSN 1678-4227. PMID 30758444.

- Oliveira, Patrick Luiz Sullivan De (2022). "Transforming a Brazilian Aeronaut into a French Hero: Celebrity, Spectacle, and Technological Cosmopolitanism in the Turn-of-the-Century Atlantic*". Past & Present. 54 (1): 235–275. doi:10.1093/pastj/gtab011.