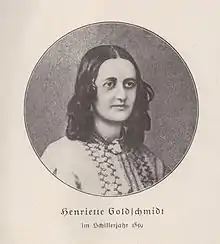

Henriette Goldschmidt

Henriette Goldschmidt (1825–1920) was a German Jewish feminist, pedagogist and social worker. She was one of the founders of the German Women's Association (German: Allgemeiner Deutscher Frauenverein) and worked to improve women's rights to access education and employment. As part of that effort, she founded the Society for Family Education and for People's Welfare (German: Verein fuer Familienerziehung und Volkswohl) and the first school offering higher education to women in Germany.

Henriette Goldschmidt | |

|---|---|

circa 1910 | |

| Born | Henriette Benas 23 November 1825 |

| Died | 30 January 1920 (aged 94) |

| Nationality | German |

| Occupation(s) | education activist, women's rights activist and social worker |

| Years active | 1865–1917 |

| Known for | founding first higher education school for women in Germany |

Early life

Henriette Benas was born on 23 November 1825 in Krotoschin, Province of Posen, Kingdom of Prussia, to Eva (née Laski) and the Jewish merchant, Levin Benas. Her mother died when she was five years old, and her father remarried an illiterate woman, who was not a nurturing maternal figure. Benas completed school at the Höhere Töchterschule at age 14,[1] where her education was limited to subjects which taught women how to be effective housewives.[2] She supplemented her meager education by reading German classics and the newspaper, Breslauer Zeitung, which aroused her early interest in politics.[3] In 1853, Benas married her cousin, Abraham Meir Goldschmidt, a widower with three sons, who was the rabbi of the Warsaw German-Jewish congregation. Five years later, her husband was appointed to succeed Adolf Jellinek as rabbi of Leipzig and the family relocated.[3]

Activism

Goldschmidt equated the move to the university town of Leipzig with an awakening to freedom and humanitarian spirit. She quickly became involved in the German-Jewish community[3] and was exposed to the ideas of Friedrich Fröbel, founder of the early-childhood kindergarten education system. Encouraged by her husband to pursue her interests in education, Goldschmidt studied history, literature, pedagogy and philosophy on her own.[4] In 1865, she, Louise Otto-Peters and Auguste Schmidt organized a conference of German women and founded the German Women's Association (German: Allgemeiner Deutscher Frauenverein) to work towards improving the lives of women. Goldschmidt had initially been hesitant about becoming a board member of the group, as the legal statutes at that time forbade women voting in volunteer organizations, but with her husband's encouragement, she became an active member. Between 1867 and 1906, she served as a member of the board and presented many lectures for the organization.[3]

In 1867, Goldschmidt organized petition drives for submission to the Reichstag in support of women's rights to access education and employment and she was a signatory to the petition to protect illegitimate children.[5] She also proposed that women be participants in their communities, because women would lend a sensitivity to dealing with culturally divisive issues. The following year, she proposed a mandatory social service initiative requiring women to serve for a year in social work.[3] In 1871, Goldschmidt founded the Society for Family Education and for People's Welfare (German: Verein fuer Familienerziehung und Volkswohl),[5] with the goal of training kindergarten teachers in the Fröbel method. She served as president of the organization for over four decades. By the following year, the organization was sponsoring teaching seminars to a growing number of adherents[1] and had opened a public kindergarten.[3] By 1878, she organized the High School for Ladies (German: Lyzeum für Damen), where professors from the University of Leipzig gave lectures to students. Because women were barred from attending college, and only a few private schools offered inferior education, the lectures were attended by hundreds of women and offered them the chance for not only an education, but employment as a teacher.[3]

_721.jpg.webp)

In 1889, the Jewish community sponsored a donation drive and purchased a house for the organization's operations. It was located at 16 Weststraße (later named Friedrich-Ebert-Straße) and became not only Golschmidt's home after her husband's death, but the center of women's education, sponsoring educational courses and lectures, as well as cultural and social events. Members of the association were also allowed to reside in the house and both the writer Josephine Siebe and educator Anna Zabel were known to have lived there.[4] In 1898 Goldschmidt and Auguste Schmidt, on behalf of the German Women's Association prepared a petition to establish the Fröbel educational method as the official municipal and state educational system. The petition asked for kindergartens to come under state standardization and supervision, with mandatory attendance for all children. They were met with waves of opposition from those who saw forced education as supplanting familial rights to children's upbringing and accused the women of trying to destroy the family. There were also opponents who saw the measure as forcing children of different social classes to mix.[1] Though Goldschmidt defended the plan, publishing a response to her critics Ist der Kindergarten eine Erziehungs- oder Zwangsanstalt? (Is kindergarten an educational institution or forced?) in 1901,[6] it was ultimately defeated.[1]

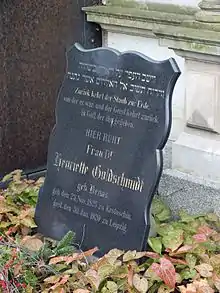

Goldschmidt did not give up and continued writing and giving speeches on the need for kindergartens and women's education.[1] In 1906, women were finally admitted to university study in Germany,[4] but the coursework did not prepare women to meet their societal obligations, as Goldschmidt believed that the natural calling of woman was to transform society through their cultural involvement.[1] She strove to fill a gap and not compete with university studies[3] and in 1911, Goldschmidt achieved the high point of her career, with the establishment of the first institution in Germany offering higher education specifically to women.[5] The Leipzig College for Women (German: Hochschule für Frauen zu Leipzig) designed its classes for women[3] as a means of formalizing Goldschmidt's vision of womanhood. It aimed to teach women to participate in the intellectual life of their culture, prepare them to be successful mothers and teachers, and to develop a sensitivity to the needs of their community and the skills to perform charitable works to help their community.[1] Once again, she utilized professors from the University of Leipzig, to supplement the coursework, but Goldschmidt and Agnes Gosche taught classes between 1911 and 1913.[4] After the 1916-1917 term, Goldschmidt retired and turned the operation of the school over to the Saxon Ministry of Worship and Public Instruction.[1] Goldschmidt died on 30 January 1920 in Leipzig, Weimar Republic[1] and was buried in the Old Jewish Cemetery of Leipzig.[4]

Legacy

In 1921, the clubhouse of the Society for Family Education and for People's Welfare was renamed as the Henriette Goldschmidt House, in her honor.[4] But, that same year, the society was dissolved and merged with the Henri Hinrichsen Foundation, with Hinrichsen in charge of the school.[7] During the Nazi era, the school eradicated any ties to its Jewish founder, Goldschmidt and later director, Hinrichsen, also barring admittance to Jewish girls. With the establishment of East Germany, the school was renamed after Henriette Goldschmidt and served as a pedagogical training school for kindergarten teachers. In 1992, the school, now called the Henriette-Goldschmidt Vocational School, became a technical training institution for social work and special education.[4] While the school survived, in 1999, the city demolished the Henriette Goldschmidt House, despite protests, for a road expansion, which never took place.[7][8]

There are two public plaques honoring Goldschmidt in Leipzig. One was dedicated on the 75th anniversary in 1986 at the entry to the Henriette Goldschmidt School, which states: "Here in 1911 the Academy of Women opened, initiated and supported by the women's rights activist and Fröbel educator Henriette Goldschmidt (1825–1920), financially made possible by Dr. Henri Hinrichsen (1868–1942)." The second plaque in honor of Goldschmidt was affixed to a house located at 7 Spittastraße in 1996 to mark the location of the first children's day care center. A bust of Goldschmidt's likeness was cast in 2001 to mark the 90th anniversary of the school. The original is in the Leipzig Museum of Fine Arts and a replica is on a stele at the Henriette Goldschmidt School with a plaque inscribed to match the one removed by the Nazis and originally added to the wall by Hinrichsen, with the words "To the noble pursuit of German women".[4]

Selected works

- Goldschmidt, Henriette (1868). Vortrag von zum 25 jährigen Schriftstellerjubiläum der Frau L. Otto-Peters, etc (Speech) (in German). Frauenbildungs-Verein zu Leipzig, Germany. OCLC 559031378.

- Goldschmidt, Henriette (6 April 1870). Die Frauenfrage eine Culturfrage (Speech) (in German). Frauenbildungs-Verein zu Leipzig, Germany. OCLC 68902008.

- Goldschmidt, Henriette (3 March 1871). Die Frau im Zusammenhang mit dem Volks- und Staatsleben (Speech) (in German). Frauenbildungs-Verein zu Cassel, Germany: Amelang. OCLC 610117786.

- Goldschmidt, Henriette (1872). Der Kindergarten in seiner Bedeutung für die Erziehung des weiblichen Geschlechts Vortrag gehalten am 15 Januar 1872 in Leipzig im Verein für Familien- und Volkserziehung (in German). Leipzig, Germany: Sturm und Koppe. OCLC 179711254.

- Goldschmidt, Henriette (8 December 1873). Einfluss der Frau in Familie und Gesellschaft (Speech) (in German). Verein für Familien und Volks-Erziehung zu Leipzig, Germany: Fischer. OCLC 610117755.

- Goldschmidt, Henriette (1874). Die Stellung der Kindergartenschule: in dem Organismus des Fortbildungsunterrichts für die weibliche Jugend: Vortrag gehalten im Verein für Familien- und Volkserziehung zu Leipzig am 17 November 1874 (in German). Leipzig, Germany: Commission der Serig'schen Buchhandlung. OCLC 45566846.

- Goldschmidt, Henriette (27 September 1877). Die Frauenfrage innerhalb der modernen Culturentwickelung (Speech) (in German). Eröffnung des Frauentages zu Hannover, Germany: Kniep. OCLC 819215505.

- Goldschmidt, Henriette (1882). Ideen über weibliche Erziehung im Zusammenhange mit dem System Friedrich Fröbels; sechs Vorträge (in German). Leipzig, Germany: Reißner. OCLC 632790861.

- Goldschmidt, Henriette (1896). Festschrift zum fünfundzwanzigjährigen Jubiläum (in German). Leipzig, Germany: Verein für Familien- und Volkserziehung. OCLC 255707743.

- Goldschmidt, Henriette; von Marenholtz-Bülow, Bertha (1896). Bertha von Marenholtz-Bülow: ihr Leben und Wirken im Dienste der Erziehungslehre Friedrich Fröbels (in German). Hamburg, Germany: Verlagsanstalt und Druckerei Actien-Gesellschaft. OCLC 252401405.

- Goldschmidt, Henriette (24 May 1899). Das Erziehungswerk Friedrich Fröbels (Speech) (in German). Blankenburg Rathaussaale zu Thuringia, Germany: Kahle. OCLC 179989971.

- Goldschmidt, Henriette (1901). Ist der Kindergarten eine Erziehungs–oder Zwangsanstalt? Zur Abwehr und Erwiderung auf Herrn K.O. Beetr's Kindergartenzwang! Ein Weck und Mahnruf an Deutschlands Eltern und Lehrer (in German). Wiesbaden, Germany: Emil Behrend. OCLC 163028695.

- Goldschmidt, Henriette (1909). Was ich von Fröbel lernte und lehrte Versuch einer kulturgeschichtlichen Begründung der Fröbel'schen Erziehungslehre (in German). Leipzig, Germany: Akademische Verlagsgesellschaft. OCLC 174398262.

- Goldschmidt, Henriette (1911). Vom Kindergarten zur Hochschule für Frauen: Verein für Familien- und Volkserziehung, Leipzig. 1871; eine Denkschrift (in German). Leipzig, Germany: Verein. OCLC 250742377.

- Goldschmidt, Henriette (1918). Vom Kindergarten zur Hochschule für Frauen ein Rückblick auf die Anfänge der deutschen Frauenbewegung und das Erziehungswerk Friedrich Fröbels (in German). Leipzig, Germany: Quelle & Meyer. OCLC 179950020.

References

Citations

Sources

- Berger, Manfred (1995). Textor, Martin R. (ed.). "Frauen in der Geschichte des Kindergartens: Henriette Goldschmidt" [Women in the history of the kindergarten: Henriette Goldschmidt]. Das Kita-Handbuch (in German). Würzburg, Germany.

- Doff, Sabine (April 2005). "Weiblichkeit und Bildung: Ideengeschichtliche Grundlage für die Etablierung des höheren Mädchenschulwesens in Deutschland" [Femininity and education: Ideas on the historical basis for the establishment of the girls' high school system in Germany] (PDF). Goethezeitportal (in German). Munich, Germany. Retrieved 29 March 2016.

- Fassmann, Maya (1 March 2009). "Henriette Goldschmidt (1825-1920)". Jewish Women: A Comprehensive Historical Encyclopedia. Brookline, Massachusetts: Jewish Women's Archive. Retrieved 29 March 2016.

- Goldschmidt, Henriette (1901). Ist der Kindergarten eine Erziehungs–oder Zwangsanstalt?: Zur Abwehr und Erwiderung auf Herrn K.O. Beetr's Kindergartenzwang! Ein Weck und Mahnruf an Deutschlands Eltern und Lehrer [Is kindergarten an educational institution or forced?: As a defense and reply to Mr K.O. Beetr's compulsory kindergarten! A wake-up call and exhortation to German parents and teachers] (in German). Wiesbaden, Germany: Emil Behrend. OCLC 163028695.

- Jensen, Annette (9 December 1999). "Die Leipziger Frauenfrage" [Leipziger woman question]. Die Zeit (in German). Hamburg, Germany. Retrieved 29 March 2016.

- Kämmerer, Gerlinde (2013). "Biographien historischer Frauenpersönlichkeiten: Bildung—Henriette Goldschmidt, geb. Benas" [Biographies of historic female personalities: Education—Henriette Goldschmidt, born Benas]. 1000 Jahre Leipzig—100 Frauenporträts (in German). Leipzig, Germany: Stadt Leipzig. Archived from the original on 15 June 2016. Retrieved 29 March 2016.

- Spear, Otto Immanuel (2008). "Henriette Goldschmidt (née Benas)". Jewish Virtual Library. Chevy Chase, Maryland: Encyclopaedia Judaica. Retrieved 29 March 2016.

- "Henriette-Goldschmidt-Haus Leipzig Abriss-Pläne für Goldschmidt-Haus bestätigt und vollzogen" [Henriette-Goldschmidt-Haus Leipzig Confirmed demolition plans for Goldschmidt House completed] (in German). Leipzig, Germany: Leipziger Internet Zeitung. 16 March 2010. Retrieved 29 March 2016.