Hellenistic sculpture

Hellenistic sculpture represents one of the most important expressions of Hellenistic culture, and the final stage in the evolution of Ancient Greek sculpture. The definition of its chronological duration, as well as its characteristics and meaning, have been the subject of much discussion among art historians, and it seems that a consensus is far from being reached.[1] The Hellenistic period is usually considered to comprise the interval between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC, and the conquest of Egypt by the Romans in 30 BC.[2] Its generic characteristics are defined by eclecticism, secularism, and historicism, building on the heritage of classical Greek sculpture and assimilating Eastern influences.[3]

Among his original contributions to the Greek tradition of sculpture were the development of new techniques, the refinement of the representation of human anatomy and emotional expression, and a change in the goals and approaches to art, abandoning the generic for the specific. This translated into the abandonment of the classical idealism of an ethical and pedagogical character in exchange for an emphasis on everyday human aspects and the directing of production toward purely aesthetic and, occasionally, propagandistic ends. The attention paid to man and his inner life, his emotions, his common problems and longings, resulted in a realist style that tended to reinforce the dramatic, the prosaic, and the moving, and with this appeared the first individualized and verisimilitude portraits in Western art. At the same time, a great expansion of the subject matter occurred, with the inclusion of depictions of old age and childhood, of minor non-Olympian deities and secondary characters from Greek mythology, and of figures of the people in their activities.[4][5]

The taste for historicism and erudition that characterized the Hellenistic period was reflected in sculpture in such a way as to encourage the production of new works of a deliberately retrospective nature, and also of literal copies of ancient works, especially in view of the avid demand for famous classicist compositions by the large Roman consumer market. As a consequence, Hellenistic sculpture became a central influence in the entire history of sculpture in Ancient Rome. Through Hellenized Rome, an invaluable collection of formal models and copies of important pieces by famous Greek authors was preserved for posterity, whose originals eventually disappeared in later times, and without which our knowledge of Ancient Greek sculpture would be much poorer.[6] On the other hand, Alexander's imperialism towards the East took Greek art to distant regions of Asia, influencing the artistic productions of several Eastern cultures, giving rise to a series of hybrid stylistic derivations and the formulation of new sculptural typologies, among which perhaps the most seminal in the East was the foundation of Buddha iconography, until then forbidden by Buddhist tradition.[7]

For the modern West, Hellenistic sculpture was important as a strong influence on Renaissance, Baroque, and Neoclassical production.[8] In the 19th century Hellenistic sculpture fell into disfavor and came to be seen as a mere degeneration of the classical ideal, a prejudice that penetrated into the 20th century and only recently has begun to be put aside, through the multiplication of more comprehensive current research on this subject, and although its value is still questioned by resistant nuclei of the critics and its study is made difficult for a series of technical reasons, it seems that the full rehabilitation of Hellenistic sculpture among scholars is only a matter of time, because for the general public it has already revealed itself to be of great interest, guaranteeing the success of the exhibitions where it is shown.[9][10][11][12]

Background

%252C_found_in_Pompeii%252C_Moi%252C_Auguste%252C_Empereur_de_Rome_exhibition%252C_Grand_Palais%252C_Paris.jpg.webp)

The sculpture of Classicism, the period immediately preceding the Hellenistic period, was built on a powerful ethical framework that had its bases in the archaic tradition of Greek society, where the ruling aristocracy had formulated for itself the ideal of arete, a set of virtues that should be cultivated for the formation of a strong morality and a socially apt, versatile and efficient character. In parallel, the concept of kalokagathia was formulated, which affirmed the identity between Virtue and Beauty. Expressing these concepts in plastic forms, a new formal canon was born, developed by Polychaetus and the Phidias group, which sought the creation of human forms that were both naturalistic and ideal, through whose perfect and balanced beauty the virtues of the spirit could be perceived.[13][14][15]

These ideas had been reinforced by the contribution of philosophers such as Pythagoras, who said that art was an effective power, capable of influencing people for good or evil, according to whether they obeyed or violated certain principles of balance and form. He also said that art should imitate the divine order, which was based on defined numerical relationships, and expressed in the harmony, coherence, and symmetry of natural objects. He had worked his ideas out from his research with mathematics and music, but it wasn't long before they were applied to the other arts, encouraging an eminently ethical use for artistic creation and fostering collective rather than individual values, which Plato's idealistic philosophy eloquently corroborated.[16]

Context and characteristics

The spirit of Hellenistic culture began to form with the Macedonian conquest of Greece and Alexander's military expeditions to the East, which carried classical Greek culture to the banks of the Indus River and gave rise to the establishment of several Greco-Oriental kingdoms. The culture of classical Greece, on which Macedonia was dependent, was defined within a relatively limited worldview, circumscribed to the city-state, the polis. Even though the Greeks founded a number of colonies around the Mediterranean and the Black Sea, and maintained contact with several other countries, their cultural reference remained the metropolis, whose society was based on the experience of defined groups living in the most important cities. According to Jerome Pollitt, "a classical Greek might travel voluntarily to seek adventure, but once the adventure was over his intention was to return to the small, safe, familiar society where his identity had been established.[17]

With the Macedonian presence on Greek soil, and with Alexander's imperialistic spirit, this more or less static world suffers a profound shake-up and begins to experience a transformation that would make that traditional, communal life a thing of the past. Alexander founded several cities in his campaigns, encouraging important migrations of Greek populations, including thousands of artists,[18] who went to try their luck in an entirely foreign ethnic and cultural environment, building new societies whose dominant note was insecurity and mobility, at all levels. After his death, his successors engaged in a series of power struggles, causing the collapse of the empire amidst intense turmoil and a widespread loss of the old references and expectations of Greco-Macedonian society.[19][20]

In the opposite direction, Rome began its bellicose and predatory expansion, and self-confidence, idealism and the old social and religious collective values declined, generating a withdrawal and disenchantment in individuals in face of the moral poverty, political cynicism and violence of the times, aspects that were masked by the search for mere pleasure and formalized artistically through a realism sometimes full of drama. The diverse origins of the colonists and the notorious Greco-Macedonian xenophobia made lasting and reliable social alliances difficult in the conquered lands, and for the artists, patronage was subject to personal whims and frequent oscillations in the taste of the ruling elite as the political leanings changed. No wonder then that Pliny, a classicist, said that the 3rd century BC was a time when the arts disappeared. For some, these times may have had an exciting appeal, but the philosophers of the time point to an acute awareness that the phase was one of great instability,[19][20] with even a veiled sense of guilt for the collapse of the old moral values in the face of the new worldly and corrupt urban landscape, which would be the source of a very long tradition of seeking a return to the simple life, primitive and authentic peasant life, even if this return could never be realized in fact except symbolically, in the periodic classicist revivalisms - the first of which would occur at the end of the Hellenistic period - and within the dreams of poetic pastoralism that populate the history of art from those times to the present day.[21]

The philosophy of the Hellenistic period carried forward the debate on aesthetics that had been inaugurated by Socrates and Plato in previous years. Plato's ethics preached that art at best was only an imperfect simulacrum of abstract truths, and therefore lacked deep value and credibility, and should in all cases serve a moral and pedagogical cause. Socrates before him had suggested that art could express individual pathos, and Aristotle, taking this motto and opposing the general lines of Platonic idealistic thought on aesthetics, approached the issue empirically, trying to discover other uses and meanings for artists' creations. He developed the concept of catharsis, supposing that art could educate the spirit by simulating the human emotional weaknesses themselves, he widened the way for individual emotionalism and visions to be cultivated, and with this he relativized the function and reading of art and gave prestige to individual creativity. At the same time, it favored the secularization of its character, making room for the use of sculpture as a form of political and personal propaganda.[22]

Once primarily devoted to the sacred function and the public commemoration of heroes and athletes, whose rationale was primarily ethical, didactic, and idealistic, the elite now desired works that were primarily personalistically motivated and whose character was primarily decorative. Even statues of gods came to be seen more as "works of art" than as symbolic instruments of communication with the invisible worlds. With this, private taste - which was not always the most refined and cultured - began to prevail over collective conventions, favoring a purely aesthetic practice that widely opened its thematic range to include the picturesque, the trivial, the painful, the comic, the terrifying, the sensual, the shapeless, and the grotesque.[23][24] Accompanying these changes appears for the first time in Western art a definite inclination to read works allegorically. A decline in the credibility of the ancient myths causes moral principles to be personified in other ways, and whereas in earlier art the gods embodied a series of immaterial attributes, now conversely the abstractions themselves, such as courage, forgiveness, wisdom, combativeness, take on human form and are individually deified.[25]

Formally the general characteristics of Hellenistic sculpture derive mainly from the work of three great artists, Scopas, Praxiteles and Lysippos, who lead the transition from Classicism to the Hellenistic tradition in the mid 4th century BC.[26] In terms of expressiveness and narrative character their production has much more to do with Hellenistic than with the High Classicism that preceded it, although on the ground of style itself their classical origin remains evident. They begin the process of abandoning idealization in order to bring representation down to the human level, even when it comes to the image of deities. Not without a hint of irony Jerome Pollitt comments on a work attributed to Praxitheles, the Apollo Sauroctonos, and sees in it a burlesque image of the decay of status from a virile dragon-killing god to an effeminate effete who can barely scare away a common lizard, in a period when the ancient myths were beginning to lose their divine aura and their real power of inspiration, and were beginning to be discredited in a society that was strongly profane and urban, but which could therefore turn its attention more intensely to the portrait of man, his specific problems and successes, and his inner universe.[27]

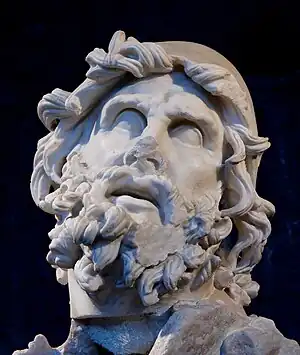

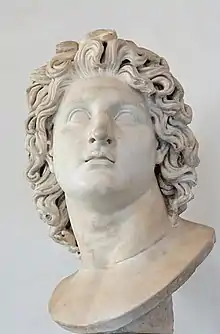

On the other hand, Alexander the Great himself is attributed an important influence on the introduction of new modes of sculptural representation. In the portrait of rulers, young, athletic, unshaven figures were preferred, when this genre was previously typified by mature, bearded figures. The various portraits of the general also became models for the representation of the gods Apollo and Helios, and of the river deities, including his gaze turned upwards and his dense, long, and loose hair, typical traits of those portraits. With a centralizing personality, Alexander's charisma promoted a reorganization in the scenes of battles and hunts, starting to highlight the figure of a leader, when before it was usual to treat all the characters with the same visual importance in compositions without a main focus. Finally, the fame of his horse Bucephalus produced a tendency to magnify the size of the representations of these animals in relation to previous periods.[28]

The description of Hellenistic sculpture, a subject of great complexity which is still the source of much controversy and uncertainty, can only be made, in a summary such as this, generically. The multiplicity of production centers, the great mobility of sculptors among them, and the prevailing stylistic freedom have created a multifaceted and multifocal panorama, where various tendencies coexist and intersect,[29] but the mentality of the Hellenists, and its repercussions on the art of sculpture, can be more or less defined through five dominant lines:

I. An obsessive preoccupation with fate and its unpredictable and changeable character, visible in the proliferation of philosophical writings and iconography on Tyche, the goddess who embodied Luck or Fortune - conceived in an interpretation associated with destiny - and in the portraiture of Alexander, a personality who always considered himself protected by Fortune, for even when bad luck seemed to threaten him, he was able to reverse the situation in his favor. Likewise, mirroring this interest was the depiction of events when individual fortunes changed dramatically, as in moments of great success or great failure.[30]

II. A sense of the theatricality of life, reflected in the taste for the spectacular, for the great public manifestations of regal pomp, for the dramatic and vehement pronouncements of orators, for profane and religious festivals sumptuous and stimulating to the senses,[31] and for sculptures where the sense of drama, of exaltation, of movement, of tumult, of rapture, of the extraordinary was intentionally sought in a style whose tenor was narrative and rhetorical. There was even a technical terminology borrowed from literary rhetoric to describe the formal elements favored in Hellenistic sculpture: auxesis (amplification), makrology (expansion), dilogia (repetition), pallilogia (recapitulation), megaloprepeia (grandeur), deinosis (intensity), ekplexis (shock), enargeia (vivacity), anthitesis (contrast), and pathos (emotional drama).[32]

III. A tendency toward erudition, manifested in the expanded interest in the geography and history of other countries, in books describing foreign ethnic features and their cultural wonders, in linguistics, with the elaboration of grammars, dictionaries, and compendiums of cultured and difficult words. It was the time when great libraries and museums were founded, such as the one in Alexandria, when planned and systematized art collections were formed, and archaisms were cultivated in the various arts, including sculpture, which evidenced the knowledge of renowned authors and the possession of an illustrated spirit. Thus, styles from previous phases were imitated in literal copies of old works, or their principles were assimilated to compose new pieces, often juxtaposing traces of different schools and periods in the same work, or integrating exotic stylistic elements brought from the East, which gave the production an eclectic and historicist character. At the same time the sculptors rivaled in demonstrations of technical virtuosity in the extreme refinement of the stone carving, visible in many specimens.[33] The classical heritage remained the original reference standard, the language common to all, upon which innovations could be better identified and appreciated, even when they took on a decidedly anti-classical feature. Although this historicism was born from a look to the past, it worked on themes that were still valid, and the resulting eclecticism, although aesthetically ambiguous, created a repertoire of new forms and updated old ones that contributed to a greater artistic richness and variety to the period, formulating a new language that was essentially current and cosmopolitan for them [34][35]

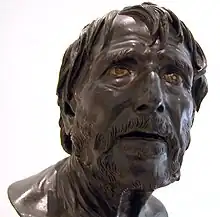

IV. The individualistic nature, from the notion of autarky, a concept that preached individual autonomy and independence as the basis for happiness, and indirectly encouraged the development of a wandering and adaptable spirit, averse to conventionalisms and bound to its unique and essential nature, capable of adapting to any situation, typified by the adventurous mercenary and synthesized in the cult of personality. This individualism, which permeated the entire philosophy and religion of the period, also influenced literature, with the appearance of biographies and memoirs of illustrious characters, and sculpture, in the sense that the realistic representation of picturesque types and of the inner world of the characters, expressed through the emotions stamped on their faces and body attitudes, was now sought after. This desire for artistic realism, together with the praise of personality, gave rise to the first realistic portraits in Western art, which represent in Jerome Pollitt's view the most important achievement of all Hellenistic art.[36]

V. A cosmopolitan vision, the corollary of the characteristics invoked above and the mark of an expanded and perpetually changing world, subject to a multiplicity of forces, where different nations were seen by the philosophers as fraternal participants in a universal community and individuals as unique agents of their evolution and responsible for their own lives, no longer privileged by birth or nationality, synthesizing a humanism that over time dissolved much of the ancient Greek dislike for the barbarians, opened space for the creation of a liberal, pragmatic, and self-sufficient bourgeoisie - a substantial new market for sculpture - and made possible the production of works where even physical decay, vice, and poverty could be empathetically and comprehensively represented.[37][38]

Chronology

One of the first important studies on the subject of Hellenistic sculpture, Stilphasen der hellenistischen Plastik (1924), by Gerhard Krahmer, divided it into three phases, which greatly influenced the subsequent methodology of analysis:

- the first, including the late 4th and early 3rd century BC, called "simple," where an eclectic stylistic mix derived from the work of the aforementioned masters predominates, and their works tend to be organized around a central focus of attention;

- the second, comprising the rest of the third century until the middle of the second century BC, a stage whose characterization is very difficult due to the scarcity of testimonies, but which seems to have given rise to new typologies and to the most dramatic tendency in sculpture, and for this reason it is called "pompous", "baroque" or "pathetic";

- the final phase, called "open", between the middle of the 2nd century and the 1st century BC, when the compositions are strongly centrifugal, eclecticism is accentuated and a revival of the classical tradition takes place.[39]

Later studies have proposed alternative divisions, but modern research, however, tends to consider that a simply chronological appreciation tends to be misleading, leading one to believe that the style evolved linearly, when the evidence indicates that the process was rather cumulative, rather than successive.[40]

Polieucto: Portrait of Demosthenes, c. 280, example of the first phase.

Polieucto: Portrait of Demosthenes, c. 280, example of the first phase. Suicidal Galatian, 2nd century BC Roman copy. Example of the second phase.

Suicidal Galatian, 2nd century BC Roman copy. Example of the second phase. Taurisks and Apollonius of Tralles: Farnese Bull, 2nd century BC, Roman copy. Example of the second phase.

Taurisks and Apollonius of Tralles: Farnese Bull, 2nd century BC, Roman copy. Example of the second phase. Pasíteles: Atalanta, 1st century BC, Greek original. Example of the third phase

Pasíteles: Atalanta, 1st century BC, Greek original. Example of the third phase

Main production centers

Greece

Greece remained a productive region throughout the Hellenistic period. Although Athens lost its ancient primacy, it remained active - and in fact started a neoclassical movement through the Neo-Attic School, of great influence on Roman sculpture - along with Olympia, Argos, Delphi, and Corinth, while several new centers were established for example in Messene, Miletus, Priene, Cyprus, Samothrace, and Magnesia. Worth special attention, however, are Rhodes and Magna Graecia. Tangra also deserves some attention, but will be dealt with in the section on Terracottas, and Pergamos, even though it developed the typology of wounded warriors and Amazons, much appreciated and with specimens of the highest level, will appear in the section on Architectural Sculpture because of the major importance of its Altar of Zeus.

The island of Rhodes was for most of the Hellenistic period a fairly active center of sculpture production, attracting masters from various backgrounds. After 167 BC its importance as a commercial center suffered a decline, facing competition from the free port of Delos, but at this stage the local patrons seem to have made a special effort to encourage the native artists. For quite some time Rhodes was judged to be a hotbed of innovations in sculpture, associating it with the formulation of the "baroque" style of the Hellenistic period, but recent studies have revised this opinion and placed the island's output within a more modest profile of originality, having possibly received the influence of another major center, Pergamos. Even so, many workshops flourished there, and ancient writers such as Pliny the Elder say that Rhodes boasted three thousand statues, and about a thousand of them of enormous dimensions, which would have been enough to make the island famous had they not been eclipsed by the famous Colossus, a gigantic bronze image representing Helios, the local patron god, designed around 304 by Chares of Lindos, a pupil of Lysippus. Pliny still mentions the name of Briaxis as the author of some important pieces, and that of Lysippus as the creator of another colossal Helios, depicted in a quadriga. It is also possibly a copy of an original from Rhodes, produced by Taurisik and Apollonius of Trales, the famous Farnese Bull, now in Naples. Atenodorus, Polydorus and Agesander, three natives of Rhodes, are the authors of one of the most paradigmatic works of the Baroque phase of the Hellenistic period, the Laocoön and His Sons, and of another remarkable set of sculptures found in the cave of the Villa of Tiberius in Sperlonga, depicting scenes from the adventures of Odysseus. Finally, it has been suggested that another work of great fame, the Victory of Samothrace, is a production of Rhodes, but there is no conclusive evidence.[41]

Syracuse was, before it was devastated by the Romans, one of the richest cities in Magna Grecia, with a flourishing sculptural activity. After the Roman passage, which deprived it of its entire collection, the city regained some artistic prestige through the production of terracotta statuary from local traditions. Other cities where there is a significant legacy are Taranto, one of the best preserved areas in terms of sculpture from the 3rd century BC, and Agrigento.[42]

.jpg.webp)

Rome

.jpg.webp)

From the origins of Rome, its sculpture was under Greek influence. First through Etruscan art, which was an interpretation of the art of the Archaic Period in Greece, and then with the contact with the Greek colonies in Magna Graecia, in the south of the Italian peninsula. Having started their expansion into the Mediterranean, in their military campaigns the Romans sacked several cities where there were large collections of Hellenistic sculpture, among them the prosperous Syracuse, dominated in 212 BC. According to accounts, the war booty was fantastic, and, taken to Rome, it began to adorn the capital, immediately displacing in public favor sculpture of Greco-Etruscan tradition. This plunder was followed by several others, Tarentum in 209, Eretria in 198, the Peloponnese in 196, Syria and Anatolia in 187, Corinth in 146, Athens in 86, and Sicily in 73-71, seizures so large that they sometimes caused indignation among the Roman senators themselves. The result, however, was to cover Rome with Hellenistic art, and to attract to the new power several craftsmen, such as Polycles, Sosicles, and Pasitles, who began to create a local school of sculpture, which was founded on the principles of Hellenistic art and was responsible for transmitting to posterity, through copies, a huge amount of celebrated Greek works and formal prototypes whose originals would later end up being lost, while formulating new typically Roman typologies. Later, Roman Hellenistic-Classical sculpture would be the transitional link to Byzantine art and would provide the basis for the development of Christian iconography.[43][44][45][46]

Etruria

The contact between Greek and Etruscan civilizations is documented since the 8th century BC, and throughout the history of Etruscan art the Greek influence remained strong. At the end of the 4th century BC, when the Etruscan Hellenistic begins, the Roman presence already began to predominate over the region, and its culture went into decline. Even so, in this period a new sculptural typology was created, that of sarcophagi with portraits, which will be discussed in the section Sarcophagi and cinerary urns. Another Etruscan contribution to Hellenistic sculpture is the formulation of the type of the seated mother with her child in her lap, known as koine, whose best known specimen is the Mater Matuta from the National Archaeological Museum in Florence.[47] Typical of the Etruscan tradition is the preference for the use of terracotta in the production of ex-votos, sophisticated decorative pieces, vases - some in the shape of a human head - and in architectural decoration, with high quality specimens in several temples in Luni, Tarquinia and elsewhere, which exhibit traces of the Eastern Hellenistic influence.[48] Finally, the Etruscans also proved to be expert craftsmen in bronze, creating a collection of full body portraits and in busts that in their naturalism approach the style of Roman sculpture in these genres.[25]

Alexandria

After Alexandria was founded, the city soon became an important center of Hellenistic culture. The famous Library, which included one of the world's first museums, was built there, and around it flourished an important group of philosophers, literati, and scientists, who made a very relevant contribution to Hellenistic culture as a whole, but in the field of sculpture, contrary to what had been thought for a long time, recent research indicates that the result was much poorer. Egypt had a long and brilliant sculptural tradition, and the Macedonian pharaohs, finding a culture firmly established, developed a dual artistic practice. For the Hellenistic elite, who lived mainly in Alexandria and had little connection with the reality of the rest of the country, a Hellenistic art was produced, and for the people an art that followed the ancient pharaonic traditions, and little interchange could be made between them.[49] Even in the field of official portraiture, duplicity was maintained, although in rare cases a significant mixture of these two contrasting styles is observed, with changes in the traditional features of hairstyles and costumes, and in the appearance of the insignia of power, showing a carefully selective adaptation of the Hellenistic style.[50][51]

Etruscan vase, second half of the 4th century

Etruscan vase, second half of the 4th century Portrait of Hor, c. 300-250 BC, Egypt

Portrait of Hor, c. 300-250 BC, Egypt Mithridates I and Hercules, Arsacid Empire

Mithridates I and Hercules, Arsacid Empire Buddha and Vajrapani, 2nd century BC, Gandhara

Buddha and Vajrapani, 2nd century BC, Gandhara

Middle East

Following the partition of the Alexandrine empire, the Hellenistic empire of the Seleucids was formed in the Middle East, with several new cities founded by Alexander and his successors. With the gradual dissolution of the old Persian institutions, many other older cities adopted an administrative model similar to the Greek polis, and within a few decades the Persian elite became Hellenized, and every aspirant to an important social position now needed to know Greek and be versed in Hellenic culture. But the impact of Hellenization, if it reached various cultural forms, did not prevail among the mass of the people and, throughout local history, proved fleeting. In the mid 3rd century BC the Seleucid Empire fragmented, giving rise to the Arsacid Empire, which soon began an expansion and eventually supplanted its mother state. In this period a process of reversion to ancient traditions began, the effect of which spread beyond the borders and determined an anti-Hellenistic reaction also in India, Syria, Arabia, Anatolia and other regions, declining local interest in sculpture.[52] While the Greco-Macedonian presence lasted, there was significant interchange of influences with the indigenous culture, and it seems that even Plato absorbed elements of Zoroastrian religion into his philosophy. In sculpture there survive from various sites high quality relics from the Seleucid period, especially in bronze, images of regal figures and diverse gods and statues, and from the Arsacid phase there are reliefs engraved on rocks, of great interest and distinctly hybrid style.[53]

India

Hellenistic art was able to influence the culture of distant countries such as India and Afghanistan, which by the time of Alexander's conquests already possessed an ancient artistic tradition. By founding Hellenistic colonies in the Punjab and Bactria, they gave rise to the so-called Ghandara School. The Hellenists were responsible for the inauguration of a new sculptural typology, of immense importance for the Buddhist religion, namely, the image of Buddha itself, when until then its representation was taboo. In it they largely preserved the Hindu artistic canons, but in other genres, less loaded with symbolism, the Western traits in statuary are more evident. This School flourished until the 5th century A.D.[54]

Architectural Sculpture

The temples and public buildings of the Hellenistic period generally do not continue the practice of lavish decoration on their facades as in previous phases, with large sculptural groups on the pediments, metopes, acroteria and friezes in relief. Apparently in this period the work concentrated more on the maintenance and restoration of old buildings than on the erection of new ones. There are several decorated Hellenistic buildings, but most of them are of little interest, either because of the low intrinsic quality of the sculpture or because of their small quantity, or their present state is so ruinous and depleted that it prevents an accurate evaluation of their value. Some exceptions to this rule, however, are precious and deserve a note. Dating from the early Hellenistic period is the temple of Artemis at Epidaurus. It had winged acroterial Nike, of which four remain, now without their wings. Her style shows a rich resourcefulness in the handling of her clothing, which achieves effects of transparency in its fluttering movement.[55] Possibly from the same period, and richer, is the temple of Athena at Ilion, ancient Troy. The date of the temple has been estimated to be around 300 BC, but that of its sculptural decoration is more problematic. It had 64 metopes, but it is not known how many were carved. Of those that survive, the most important, and practically intact, is the one showing Helios and his chariot. Others are fragmentary and depict battle scenes, and possibly one of the sets deals with the Gigantomachia. Its eclectic style suggests foreign influences.[56][57]

Also from around 300 BC is the decoration of the House of the Bulls at Delos, an unusual long and narrow building, with colonnades and profuse sculptural ornamentation, divided between metopes, a continuous frieze and acroteria on the outside, which unfortunately are quite eroded, and inside another large frieze with marine scenes and zoomorphic capitals. At the same site sculptures have been found decorating several other buildings, such as the theater, the stoa of Antigonus Gônatas, the monument to Mithradates VI Eupátor, and the House of the Trident, the latter with an unusual decoration of stucco reliefs.[58] Of uncertain dating, but possibly being another example of this phase is the Hieron of the Sanctuary of the Great Gods of Samothrace, with several reliefs of centaurs on the portico, and several statues on the north pediment, together with acroterial Nices, but these must be of much later date, possibly mid-2nd century BC[59]

Between the 3rd and 2nd centuries BC Pergamos emerged as one of the most active centers of sculpture production, due to the generous patronage of its kings Attalus I and Eumenes II. Under the first, the type of wounded warriors was developed, celebrated in the dying Galatians and Amazons, and under the second, the great Altar of Zeus was built, decorated with friezes and statuary of great expressiveness. The Altar is the richest decorated monument of the entire period and the most important achievement of the "baroque" trend, whose potential Epigonus of Pergamos, the chief sculptor of the monument, was among the first to fully understand and exploit.[60] A Gigantomachia and the story of Thelephus, the legendary founder of the city, are depicted there. In technical and thematic terms, the frieze of the Gigantomachia introduced several innovations, minimizing the importance of the background, taking to extremes the preciousness in the description of details, presenting minor deities alongside the Olympian gods, and going beyond the limits of the frieze to place characters advancing into the steps of the monument, subverting the traditional conventions that governed the relationship between statuary and architecture. On the other hand, the frieze of Thelepheus rescued the importance of the background but added unprecedented details of landscape scenes.[61][62]

Another important monument in the first half of the 2nd century is the great temple of Artemis Leucofriene in Magnesia. Among its decorations are a frieze with animals and a long frieze showing Amazonomachy, with 340 carved figures. Its quality is not of the highest, but its interest lies in the great diversity of plastic solutions, which avoid any monotony. In the same city there is an altar of Artemis with significant decoration, with many remaining fragments of human and animal figures. An entire frieze with bucraniums, however, was lost during World War II. A little later is the Altar of Dionysus in Kos, where most of a large frieze showing a Dionysian procession and battle scenes survives.[63]

Etruscan architectural sculpture

Already mentioned before, the practice of Etruscan architectural decoration deserves some additional lines because it is one of the most typical achievements of their art and because of its unique character in the Hellenistic panorama. This tradition was born already in the Archaic period, but continued throughout its history. Unlike the other Hellenistic cultures, which favored stone, the Etruscans preferred terracotta, and applied it for the decoration of the whole series of architectural elements - pediments, metopes, acroteria, capitals, friezes, etc. The compositions are characterized by a relative formal independence from the structure that holds them, and show motifs that blend Greek and local imagery. In one point where they agree with the practice of the entire Hellenistic world was the fact that all this sculpture was vividly colored. Among the richest examples of this application are the pediments of a temple at Talamone, from the 2nd century BC, showing various scenes from the story of the Seven against Thebes.[64][65]

Terracotta statuettes

Terracotta statuettes were part of Greek daily life since the prehistoric periods, but in the Hellenistic period a differentiated tradition began, of statuettes created in series from molds that worked in a naturalistic style a variety of themes and that served various purposes - decoration, ex-voto, funeral offering in a low cost practice that spread quickly throughout the Hellenic world. Tanagra, along with other cities in Boeotia, became known from the late 4th century BC onwards for its vast production of polychrome statuettes depicting mostly women and young girls dressed in sophisticated clothes, wearing fans, mirrors, hats, and other fashionable apparatuses, creating a new formal repertoire in the long tradition of ceramic statuary, believed to have been inspired by Menander's comedy.[66][67] These statues are especially attractive for the variety of gestures and postures and the refined workmanship, but although Tanagra excelled in this type of production and lent its name to this whole genre of statuary - called Tanagra figurines - there is evidence that the typical style began to develop in Athens, spreading from there to other centers. But other terracotta schools also developed, falling outside the genre of Tanagras, not always using molds, which feature a much wider variety of types, including slaves, dancers, men, old men, knights, children, deities, theatrical characters, dolls, animals, miniaturized vases, relief plates, and loose heads. Their level of quality, however, is very uneven.[68]

Lady in blue, 3rd century BC, Tanagra

Lady in blue, 3rd century BC, Tanagra.jpg.webp) Aphrodite Heyl, 2nd century BC, Asia Minor

Aphrodite Heyl, 2nd century BC, Asia Minor Figure of an actor, 2nd century, Magna Grecia

Figure of an actor, 2nd century, Magna Grecia Eros-Harpocrates, Mirina, 1st century BC

Eros-Harpocrates, Mirina, 1st century BC

Towards the end of the third century there appear the types of seated figures and that of teachers and philosophers, which exhibit serious and contemplative features, with a simplified treatment and rougher, though expressive, finish. The colors are also diversified, with lighter shades being found. Relatively few finds are connected to sacred contexts, evidencing an essentially profane use of the statuettes. Of the various deities previously found in abundance, only Eros remains a really common type, and the other gods that are occasionally identified show such humanized features that their merely decorative purpose seems well established. The mass production of this phase gains in variety by the addition of individualized details after the piece is removed from the mold and before firing, and no two pieces are found to be identical.[69]

The relative scarcity of relics, their less intact general state, and the presence in many sites of retrospective style figures complicate the study of 2nd century BC terracottas, and the frequent mixing of objects from different periods in the same archaeological stratum, perhaps caused by mass discarding, complicating dating work. The number of nude figures decreases and the number of winged images and individualized details in the serially created pieces increases, lending in many cases the appearance of hand-modeled pieces. This group of pieces has been called "additive" because of these additions, but their finish tends to be coarser. Figure and garment forms tended to lose their spiral organization and give way to more static compositions, at a time when the sophisticated and flowing tradition of the Tangagras was fading. In the transition to the 1st century BC the ancient types have already lost their vitality and the production becomes standardized, possibly even acquiring a tourist souvenir character, since by this time Greece was no more than a Roman province, and as a result of the Roman plundering of the great cities the remaining material is scarce and often badly damaged. As for the other regions, the Roman taste becomes predominant as the empire expands, barbarian influences appear, and Hellenistic terracotta production comes to an end at the end of the 1st century BC.[70]

Sarcophagi and cinerary urns

Sarcophagus of Dionysus, 230-220, Rome

Sarcophagus of Dionysus, 230-220, Rome Sarcophagus with battle scene between Greeks and Barbarians, Israel

Sarcophagus with battle scene between Greeks and Barbarians, Israel Polychrome terracotta cinerary urn cover, c. 150-120 BC, Etruscan

Polychrome terracotta cinerary urn cover, c. 150-120 BC, Etruscan Sarcophagus in Aphrodisias

Sarcophagus in Aphrodisias

Among the Greeks the custom of burial in sarcophagi was rare in the pre-Hellenistic periods. The dead were cremated or buried in discrete receptacles. But from the end of the 4th century, with the greater penetration of Eastern influences, where funeral pomp was appreciated, along with the Etruscan example, coffins for whole bodies and urns destined to receive the ashes of the cremated, in stone and terracotta, multiplied, often with sumptuous work in relief and large dimensions, bearing architectural elements such as colonnades and roof-shaped lids with acroteria, repeating the model of the temple, which gave them the character of an autonomous monument, and in these cases they could leave the closed environments of the tombs and be installed outdoors in necropolis.[71] Such artistic forms would take on great importance in the Hellenistic religious universe, and would continue later, in the Roman world and then throughout Christianity, to be greatly honored. Not only did this typology expand, but it also began to reflect, in the iconography chosen for decoration, changes in Greek conceptions about life beyond the grave, such as the motif of children portrayed as victorious heroes, symbolizing purity and immortality.[25][72]

The funeral tradition of the Etruscans was important in popularizing sarcophagi and cinerary urns during the Hellenistic period. They developed a practice of mortuary art that reached in some cases great refinement, although most pieces are more or less standardized and present an average or inferior quality. The type consists of a box decorated with varying degrees of complexity, closed by a lid on which are depicted full body portraits of the deceased, alone or in couples, reclining as if at a banquet, or as if asleep. The cinerary urns adopted the same scheme, only in smaller dimensions. Important archaeological finds have been made in Arezzo, Perugia, Cortona, Volterra, Cerveteri and Chiusi, among other cities.[73]

From the East came a marked tendency toward naturalism in the figurative scenes and a taste for abstract decoration or that used phyto- and zoomorphic motifs profusely, some very typical such as the palm leaf, elephants, and lion hunting. In Lebanon, in the royal cemetery of Sidon, several examples of fine workmanship were found, among them the famous Alexander Sarcophagus, so called because it shows scenes from the life of the conqueror in its reliefs, although it was meant to receive the body of a local potentate.[74][75] This piece is of special interest because it was found in excellent condition, still showing many traces of its original polychrome, which allowed a modern copy to be built with the reconstitution of its primitive colors (illustrated to the right), presented during the Gods in Color exhibition, an international event entirely dedicated to spreading the theme of the pictorial treatment of ancient sculpture, which is so little known to the general public, but which was a widespread practice.[25] In Ptolemaic Egypt a style of its own developed, where the major sculptural interest was in the stylized figure of the dead man lying on the covering lid, adapting the pharaonic tradition for the lower social classes.[76]

Appreciation

Although it has been almost two hundred years since Hellenistic was identified in its modern sense and the term received wider dissemination, and almost one hundred since analyses of its art on more scientific lines began, it can be said that up to now only the foundations for an understanding of this theme have been laid, and they are still extremely precarious. In the last decades, research has intensified enormously, but even though it brings a lot of new and important information, most of the time its interpretation takes place among endless polemics and disputes, overturning one after another apparently established concepts, thus arousing lively opposition from other critical sectors and throwing more confusion into a study that, according to François Chamoux, is far from defining even its starting point.[77]

Understanding and just appreciation of Hellenistic sculpture is made difficult by several factors. The dating and attribution of authorship of the works are full of doubts and inconsistencies; their provenance, function and thematic identification are often merely hypothetical; most of the originals have disappeared and are only known through Roman copies whose fidelity to the original is always an uncertainty; the primary literary sources are poor and contradictory; the known names of sculptors are few, there are no major school heads with outstanding stylistic personalities who could establish definite parameters for the chronology of the style and geographical tracing of its courses and derivations; the distinction between originals and copies can be problematic, and almost the entire 3rd century BC. C. is surprisingly depopulated with relics. Let us add that all the recent progress in criticism had - and still has - to face a strong historical prejudice against Hellenistic sculpture, which sees in it only a tasteless degeneration of Greek Classicism, a view that only a few decades ago began to be dissolved to make room for more positive and comprehensive views of its intrinsic merits,[9][78] although some still consider, with their reasons, that technical virtuosity may have replaced content, that aesthetic freedom and the privatization of taste have led to a decline in overall quality, and that the works often suffer from triviality and sentimental excesses, which easily descend into melodrama and give rise to an emphasis on the pathological side of reality.[79]

But it seems that as the years go by, Hellenistic sculpture, along with the other cultural expressions of the period, is heading for a full rehabilitation. As early as 1896, Frank Bigelow Tarbell wrote that the general public was more comfortable with the immediacy, spontaneity, variety, and popular emotional appeal of the Hellenistic style than with the "more severe and sublime creations of the Phydian era" (although he made it evident that among expert critics things were different),[80] Arnold Hauser said in 1951 that Hellenistic art, because of its internationalist hybridity, had direct relations with modernity,[81] and Brunilde Ridgway, writing in 2000, stated that the general acceptance is confirmed today, when exhibitions of Hellenistic art have attracted "hordes of visitors."[82] It is becoming increasingly clear that the period can no longer be considered merely a confused and unhappy transition between the classical Greek and imperial Roman civilizations, nor analyzed through simplifications and comparisons with other eras, that it deserves specific attention, that its artists showed their importance by preserving alive a venerable tradition while being open to innovations, to the life of the common man and to the future, they have attested their erudition in the creative handling of a great formal repertoire inherited from their predecessors, they have proved their competence by developing new techniques and narrative modes, and they have produced, at their best moments, works of extraordinary refinement and powerful plastic effect.[83][84][85] The most accurate preconceptions must be set aside when we remember the importance of the Hellenistic legacy in the immense repercussion that Hellenistic works caused when they were rediscovered in the Renaissance, as was the case with Laocoon, which influenced the work of Michelangelo himself and generations after him,[86] and when we realize the enormous popularity of pieces such as the Victory of Samothrace and especially the Venus de Milo, which could become an icon even of popular culture, a feat that very few cultured creations, ancient or modern, have achieved.[87]

Gallery

%252C_Loggia_dei_Lanzi%252C_Florence_-detail-_(26583218892).jpg.webp) Paschino group (Menelaus and Patroclus?), 3rd century BC, Roman copy

Paschino group (Menelaus and Patroclus?), 3rd century BC, Roman copy Venus Lely, 3rd- 2nd century BC, Roman copy

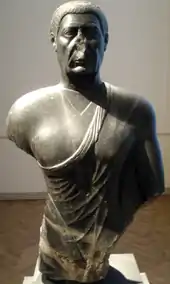

Venus Lely, 3rd- 2nd century BC, Roman copy Seleucid Prince, 3rd- 2nd century BC, modern copy

Seleucid Prince, 3rd- 2nd century BC, modern copy Old fisherman, 3rd - 2nd century BC, Roman copy

Old fisherman, 3rd - 2nd century BC, Roman copy

Faun Barberini, 2nd century BC, Roman copy

Faun Barberini, 2nd century BC, Roman copy.JPG.webp) Persian warrior, 2nd century BC, Roman copy

Persian warrior, 2nd century BC, Roman copy Dionysus drunk with a satyr and a dog, Roman copy.

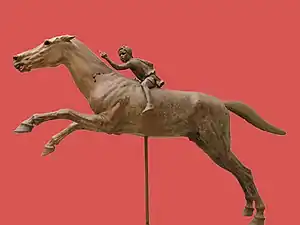

Dionysus drunk with a satyr and a dog, Roman copy. Artemisius' jockey, 2nd century BC, Greek original

Artemisius' jockey, 2nd century BC, Greek original

Papias and Aristeas: Young Centaur, late 2nd century BC, Greek original

Papias and Aristeas: Young Centaur, late 2nd century BC, Greek original Aphrodite threatening Pan with her sandal, 2nd-Ist century BC, Greek original

Aphrodite threatening Pan with her sandal, 2nd-Ist century BC, Greek original The Spinario (boy removing a thorn from his foot), 1st century BC, modern copy

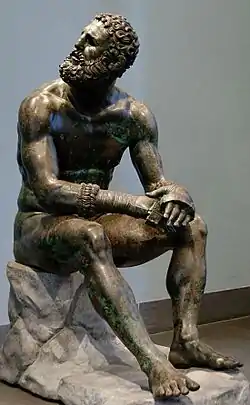

The Spinario (boy removing a thorn from his foot), 1st century BC, modern copy Boxer of the Quirinal, 1st century BC, Greek original

Boxer of the Quirinal, 1st century BC, Greek original

See also

References

- RIDGWAY, Brunilde (2001). Hellenistic sculpture I. University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 3-6

- Hellenistic Age. Encyclopaedia Britannica online. Consulta em 11 abril de 2009

- Western sculpture: Hellenistic period. Encyclopaedia Britannica online. Consulta em 11 abril de 2009

- Hellenistic Greek Sculpture. Encyclopedia of Irish and World Art.

- RIDGWAY, Brunilde (2001). p. 10

- Western sculpture: Hellenistic period. Encyclopaedia Britannica online, 22 Apr. 2009

- BANERJEE, Gauranga Nath. Hellenism in Ancient India. Read Books, 2007. pp. 74-76

- WAYWELL, Geoffrey. Art. In JENKYNS, Richard (ed.). The Legacy of Rome. Oxford University Press, 1992. pp. 295-326

- RIDGWAY, Brunilde (2001). pp. 3-ss

- CHAMOUX, François. Hellenistic civilization. Wiley-Blackwell, 1981-2002. p. 353

- GREEN, Peter. Alexander to Actium. University of California Press, 1993. p. 338

- RIDGWAY, Brunilde (2000). Hellenistic Sculpture: The styles of ca. 200-100 BC. University of Wisconsin Press, p. 4

- BOARDMAN, John. In BOARDMAN, GRIFFIN & MURRAY. p. 332

- LESSA, Fábio de Souza. Corpo e Cidadania em Atenas Clássica. In THEML, Neyde; BUSTAMANTE, Regina Maria da Cunha & LESSA, Fábio de Souza (orgs). Olhares do corpo. Mauad Editora Ltda, 2003. pp. 48-49

- STEINER, Deborah. Images in mind: Statues in Archaic and Classical Greek Literature and Thought. Princeton University Press, 2001. pp. 26-33; 35

- BEARDSLEY, Monroe. Aesthetics from classical Greece to the present. University of Alabama Press, 1966. pp. 27-28

- POLLITT, Jerome (1986). Art in the Hellenistic age. Cambridge University Press. p. 1

- TRITLE, Lawrence. Alexander and the Greeks: Artists and Soldiers, Friends and Enemies. In HECKEL, Waldemar & TRITLE, Lawrence (eds). Alexander the Great. Wiley-Blackwell, 2009. p. 129

- GREEN, Peter. pp. 337-338

- POLLITT, Jerome (1986). p. 1

- GREEN, Peter. pp. 340-341

- HONOUR, Hugh & FLEMING, John. A world history of art. Laurence King Publishing, 2005

- LING, Roger. Hellenistic and Graeco-Roman Art. In BOARDMAN, John; GRIFFIN, Jasper & MURRAY, Oswin. The Oxford History of Greece and the Hellenistic World. Oxford University Press, 2001. p. 449

- TARBELL, Frank. A History of Greek Art. BiblioBazaar, LLC, 1896-2007. p. 117

- HONOUR, Hugh & FLEMING, John

- RIDGWAY, Brunilde (2001). pp. 13-15

- POLLITT, Jerome (1972). Art and experience in classical Greece. Cambridge University Press, pp. 136; 154

- Palagia, Olga. "The Impact of Alexander the Great on the Arts of Greece". In: The Babesch Foundation. Babesch Byvanck Lectures, nº 9, 2015

- SARTON, George. Hellenistic Science and Culture in the Last Three Centuries B.C.. Courier Dover Publications, 1993. p. 502

- POLLITT, Jerome (1986). pp. 2-4

- POLLITT, Jerome (1986). pp. 4-6

- STEWART, Andrew. Baroque Classics: The Tragic Muse and the Exemplum. In PORTER, James (ed). Classical pasts. Princeton University Press, 2005. p. 128

- POLLITT, Jerome (1986). pp. 13-17

- PORTER, James. What is "Classical" about Classical Antiquity?. In PORTER, James (ed). Classical pasts. Princeton University Press, 2005. pp. 33-34

- CITRONI, Mario. The Concept of the Classical and the Canons of Model Authors in Roman Literature. In PORTER, James (ed). Classical pasts. Princeton University Press, 2005. p. 224

- POLLITT, Jerome (1986). pp. 8-10; 59-62

- POLLITT, Jerome (1986). pp. 11-13

- HAUSER, Arnold. The Social History of Art: From prehistoric times to the Middle Ages. Routledge, 1951-1999. pp. 91-94

- RIDGWAY, Brunilde (2001). pp. 5-8; 372-374

- ERSKINE, Andrew. A companion to the Hellenistic world. Wiley-Blackwell, 2003. p. 506

- POLLITT, Jerome (2000). The Phantom of a Rhodian School of Sculpture. In DE GRUMMOND, Nancy & RIDGWAY, Brunilde. From Pergamon to Sperlonga. University of California Press. pp. 92-100

- RIDGWAY, Brunilde (2001). pp. 368-369

- SARTON, George. pp. 511-514

- STRONG, Eugénie. Roman sculpture from Augustus to Constantine. Ayer Publishing. pp. 27-28

- Department of Greek and Roman Art. Roman Copies of Greek Statues. In Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000

- AWAN, Heather T. Roman Sarcophagi. In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000

- BONFANTE, Larissa. Introduction: Etruscan Studies Today. In BONFANTE, Larissa (ed). Etruscan life and afterlife. Wayne State University Press, 1986. pp. 5-12

- Verbete Arte. In CRISTOFANI, Mauro. Dizionario della civiltà etrusca. Giunti, 1999. pp. 22-25

- POLLITT, Jerome (1986). p. 250

- STANWICK, Paul. Portraits of the Ptolemies. University of Texas Press, 2002. pp. 33-ss

- SANSONE, David. Ancient Greek civilization. Wiley-Blackwell, 2004. p. 182

- YARSHATER, Ehsan. The Cambridge history of Iran. Cambridge University Press, pp. xxiii-xxv; xxxvi

- AYATOLLAHI, Habibollah et alii. The book of Iran. Alhoda UK, 2003. pp. 92-ss

- BANERJEE, Gauranga Nath. pp. 74-76

- RIDGWAY, Brunilde (2001). pp. 150-151

- RIDGWAY, Brunilde (2001). p. 154

- WEBB, Pamela A. Hellenistic architectural sculpture. University of Wisconsin Pres, 1996. pp. 48-49

- WEBB, Pamela A. pp. 134-142

- WEBB, Pamela A. pp. 145-147

- BUGH, Glenn. The Cambridge companion to the Hellenistic world. Cambridge University Press, 2006, pp. 171-172

- MARQUAND, Allan & FROTHINGHAM, Arthur. A Text Book of the History of Sculpture. Kessinger Publishing, 2005. pp. 110-111

- LING, Roger. pp. 455-461

- WEBB, Pamela A. pp. 89-91; 94; 153

- BRIGUET, Marie-François. Art. In BONFANTE, Larissa (ed). Etruscan life and afterlife. Wayne State University Press, 1986. pp. 127-133

- Verbete Talamone. In CRISTOFANI, Mauro. p. 284

- POMEROY, Sarah et alii. Ancient Greece: A Political, Social, and Cultural History. Oxford University Press US, 1998. p. 458

- Department of Greek and Roman Art. "Tanagra Figurines". In: Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000.

- THOMPSON, Dorothy. Three Centuries of Hellenistic Terracottas. In THOMPSON, Homer A. & ROTROFF, Susan I. Hellenistic pottery and terracottas. American School of Classical Studies at Athens, 1952-1966. pp. 238-239; 270-282

- THOMPSON, Dorothy. pp. 294-302; 348-349; 363-364; 371

- THOMPSON, Dorothy. pp. 369-382; 421-458

- MARQUAND, Allan. Greek Architecture. ReadBooks, 2006. p. 372

- GOLDEN, Mark. Sport and society in ancient Greece. Cambridge University Press, 1998. p. 111

- BONFANTE, Larissa. pp. 5-12 .

- DIAZ-ANDREU, Margarita. A world history of nineteenth-century archaeology. Oxford University Press, 2007. p. 165

- POLLITT, Jerome (1986). p. 19

- CORBELLI, Judith A. The Art of Death in Graeco-Roman Egypt. Osprey Publishing, 2006. pp. 44-45

- CHAMOUX, François. Hellenistic civilization. Wiley-Blackwell, 1981-2002. p. 379

- CHAMOUX, François. p. 353

- GREEN, Peter. p. 338

- TARBELL, Frank B. A History of Greek Art. Kessinger Publishing, 1896-2004. pp. 243-244

- HAUSER, Arnold. p. 91

- RIDGWAY, Brunilde (2000). p. 4 Hellenistic Sculpture: The styles of ca. 200-100 BC.

- CHAMOUX, François. p. 393

- ZANKER, Graham. Modes of viewing in Hellenistic poetry and art. University of Wisconsin Press, 2003. p. 6

- LIVINGSTONE, R. W. The Legacy of Greece. BiblioBazaar, LLC, 2007. pp. 407-408

- 500th Anniversary of the Finding of the Laocoon on the Esquiline Hill in Rome "IDC Rome: 500 Years of the Laocoon". Archived from the original on 2008-10-17. Retrieved 2022-10-22.. Institute of Design + Culture, Rome

- SHANKS, Michael. Classical Archaeology of Greece. Routledge, 1998. p. 151

External links

- Hellenistic Age - Article about Hellenistic Period, Encyclopaedia Britannica online.

- Hellenistic period - Session in the article Western Sculpture - Encyclopaedia Britannica online.

- Hellenistic Greek Sculpture - Article in Encyclopedia of Irish and World Art.