Hel (mythological being)

Hel (from Old Norse: hel, lit. 'underworld') is a female being in Norse mythology who is said to preside over an underworld realm of the same name, where she receives a portion of the dead. Hel is attested in the Poetic Edda, compiled in the 13th century from earlier traditional sources, and the Prose Edda, written in the 13th century. In addition, she is mentioned in poems recorded in Heimskringla and Egils saga that date from the 9th and 10th centuries, respectively. An episode in the Latin work Gesta Danorum, written in the 12th century by Saxo Grammaticus, is generally considered to refer to Hel, and Hel may appear on various Migration Period bracteates.

_by_Johannes_Gehrts.jpg.webp)

In the Poetic Edda, Prose Edda, and Heimskringla, Hel is referred to as a daughter of Loki. In the Prose Edda book Gylfaginning, Hel is described as having been appointed by the god Odin as ruler of a realm of the same name, located in Niflheim. In the same source, her appearance is described as half blue and half flesh-coloured and further as having a gloomy, downcast appearance. The Prose Edda details that Hel rules over vast mansions with many servants in her underworld realm and plays a key role in the attempted resurrection of the god Baldr.

Scholarly theories have been proposed about Hel's potential connections to figures appearing in the 11th-century Old English Gospel of Nicodemus and Old Norse Bartholomeus saga postola, that she may have been considered a goddess with potential Indo-European parallels in Bhavani, Kali, and Mahakali or that Hel may have become a being only as a late personification of the location of the same name.

Etymology

The Old Norse divine name Hel is identical to the name of the location over which she rules. It stems from the Proto-Germanic feminine noun *haljō- 'concealed place, the underworld' (compare with Gothic halja, Old English hel or hell, Old Frisian helle, Old Saxon hellia, Old High German hella), itself a derivative of *helan- 'to cover > conceal, hide' (compare with OE helan, OF hela, OS helan, OHG helan).[1][2] It derives, ultimately, from the Proto-Indo-European verbal root *ḱel- 'to conceal, cover, protect' (compare with Latin cēlō, Old Irish ceilid, Greek kalúptō).[2] The Old Irish masculine noun cel 'dissolution, extinction, death' is also related.[3]

Other related early Germanic terms and concepts include the compounds *halja-rūnō(n) and *halja-wītjan.[4] The feminine noun *halja-rūnō(n) is formed with *haljō- 'hell' attached to *rūno 'mystery, secret' > runes. It has descendant cognates in the Old English helle-rúne 'possessed woman, sorceress, diviner',[5] the Old High German helli-rūna 'magic', and perhaps in the Latinized Gothic form haliurunnae,[4] although its second element may derive instead from rinnan 'to run, go', leading to Gothic *haljurunna as the 'one who travels to the netherworld'.[6][7] The neutral noun *halja-wītjan is composed of the same root *haljō- attached to *wītjan (compare with Goth. un-witi 'foolishness, understanding', OE witt 'right mind, wits', OHG wizzi 'understanding'), with descendant cognates in Old Norse hel-víti 'hell', Old English helle-wíte 'hell-torment, hell', Old Saxon helli-wīti 'hell', or Middle High German helle-wīzi 'hell'.[8]

Hel is also etymologically related—although distantly in this case—to the Old Norse word Valhöll 'Valhalla', literally 'hall of the slain', and to the English word hall, both likewise deriving from Proto-Indo-European *ḱel- via the Proto-Germanic root *hallō- 'covered place, hall'.[9]

Attestations

Poetic Edda

The Poetic Edda, compiled in the 13th century from earlier traditional sources, features various poems that mention Hel. In the Poetic Edda poem Völuspá, Hel's realm is referred to as the "Halls of Hel."[10] In stanza 31 of Grímnismál, Hel is listed as living beneath one of three roots growing from the world tree Yggdrasil.[11] In Fáfnismál, the hero Sigurd stands before the mortally wounded body of the dragon Fáfnir, and states that Fáfnir lies in pieces, where "Hel can take" him.[12] In Atlamál, the phrases "Hel has half of us" and "sent off to Hel" are used in reference to death, though it could be a reference to the location and not the being, if not both.[13] In stanza 4 of Baldrs draumar, Odin rides towards the "high hall of Hel."[14]

Hel may also be alluded to in Hamðismál. Death is paraphrased as "joy of the troll-woman"[15] (or "ogress"[16]) and ostensibly it is Hel being referred to as the troll-woman or the ogre (flagð), although it may otherwise be some unspecified dís.[15][16]

Prose Edda

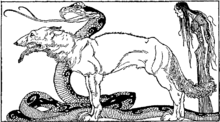

Hel receives notable mention in the Prose Edda. In chapter 34 of the book Gylfaginning, Hel is listed by High as one of the three children of Loki and Angrboða; the wolf Fenrir, the serpent Jörmungandr, and Hel. High continues that, once the gods found that these three children are being brought up in the land of Jötunheimr, and when the gods "traced prophecies that from these siblings great mischief and disaster would arise for them" then the gods expected a lot of trouble from the three children, partially due to the nature of the mother of the children, yet worse so due to the nature of their father.[17]

High says that Odin sent the gods to gather the children and bring them to him. Upon their arrival, Odin threw Jörmungandr into "that deep sea that lies round all lands," Odin threw Hel into Niflheim, and bestowed upon her authority over nine worlds, in that she must "administer board and lodging to those sent to her, and that is those who die of sickness or old age." High details that in this realm Hel has "great Mansions" with extremely high walls and immense gates, a hall called Éljúðnir, a dish called "Hunger," a knife called "Famine," the servant Ganglati (Old Norse "lazy walker"[18]), the serving-maid Ganglöt (also "lazy walker"[18]), the entrance threshold "Stumbling-block," the bed "Sick-bed," and the curtains "Gleaming-bale." High describes Hel as "half black and half flesh-coloured," adding that this makes her easily recognizable, and furthermore that Hel is "rather downcast and fierce-looking."[19]

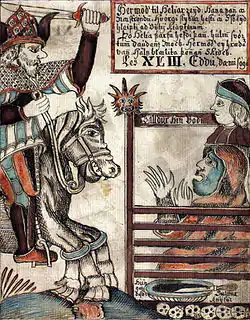

In chapter 49, High describes the events surrounding the death of the god Baldr. The goddess Frigg asks who among the Æsir will earn "all her love and favour" by riding to Hel, the location, to try to find Baldr, and offer Hel herself a ransom. The god Hermóðr volunteers and sets off upon the eight-legged horse Sleipnir to Hel. Hermóðr arrives in Hel's hall, finds his brother Baldr there, and stays the night. The next morning, Hermóðr begs Hel to allow Baldr to ride home with him, and tells her about the great weeping the Æsir have done upon Baldr's death.[20] Hel says the love people have for Baldr that Hermóðr has claimed must be tested, stating:

If all things in the world, alive or dead, weep for him, then he will be allowed to return to the Æsir. If anyone speaks against him or refuses to cry, then he will remain with Hel.[21]

Later in the chapter, after the female jötunn Þökk refuses to weep for the dead Baldr, she responds in verse, ending with "let Hel hold what she has."[22] In chapter 51, High describes the events of Ragnarök, and details that when Loki arrives at the field Vígríðr "all of Hel's people" will arrive with him.[23]

In chapter 12 of the Prose Edda book Skáldskaparmál, Hel is mentioned in a kenning for Baldr ("Hel's companion").[24] In chapter 23, "Hel's [...] relative or father" is given as a kenning for Loki.[25] In chapter 50, Hel is referenced ("to join the company of the quite monstrous wolf's sister") in the skaldic poem Ragnarsdrápa.[26]

Heimskringla

In the Heimskringla book Ynglinga saga, written in the 13th century by Snorri Sturluson, Hel is referred to, though never by name. In chapter 17, the king Dyggvi dies of sickness. A poem from the 9th-century Ynglingatal that forms the basis of Ynglinga saga is then quoted that describes Hel's taking of Dyggvi:

In chapter 45, a section from Ynglingatal is given which refers to Hel as "howes'-warder" (meaning "guardian of the graves") and as taking King Halfdan Hvitbeinn from life.[28] In chapter 46, King Eystein Halfdansson dies by being knocked overboard by a sail yard. A section from Ynglingatal follows, describing that Eystein "fared to" Hel (referred to as "Býleistr's-brother's-daughter").[29] In chapter 47, the deceased Eystein's son King Halfdan dies of an illness, and the excerpt provided in the chapter describes his fate thereafter, a portion of which references Hel:

In a stanza from Ynglingatal recorded in chapter 72 of the Heimskringla book Saga of Harald Sigurdsson, "given to Hel" is again used as a phrase to referring to death.[31]

Egils saga

The Icelanders' saga Egils saga contains the poem Sonatorrek. The saga attributes the poem to 10th-century skald Egill Skallagrímsson, and writes that it was composed by Egill after the death of his son Gunnar. The final stanza of the poem contains a mention of Hel, though not by name:

Now my course is tough:

Death, close sister

of Odin's enemy

stands on the ness:

with resolution

and without remorse

I will gladly

await my own.[32]

Gesta Danorum

In the account of Baldr's death in Saxo Grammaticus' early 13th century work Gesta Danorum, the dying Baldr has a dream visitation from Proserpina (here translated as "the goddess of death"):

The following night the goddess of death appeared to him in a dream standing at his side, and declared that in three days time she would clasp him in her arms. It was no idle vision, for after three days the acute pain of his injury brought his end.[33]

Scholars have assumed that Saxo used Proserpina as a goddess equivalent to the Norse Hel.[34]

Archaeological record

It has been suggested that several imitation medallions and bracteates of the Migration Period (ca. first centuries AD) feature depictions of Hel. In particular the bracteates IK 14 and IK 124 depict a rider traveling down a slope and coming upon a female being holding a scepter or a staff. The downward slope may indicate that the rider is traveling towards the realm of the dead and the woman with the scepter may be a female ruler of that realm, corresponding to Hel.[35]

Some B-class bracteates showing three godly figures have been interpreted as depicting Baldr's death, the best known of these is the Fakse bracteate. Two of the figures are understood to be Baldr and Odin while both Loki and Hel have been proposed as candidates for the third figure. If it is Hel she is presumably greeting the dying Baldr as he comes to her realm.[36]

Scholarly reception

Seo Hell

The Old English Gospel of Nicodemus, preserved in two manuscripts from the 11th century, contains a female figure referred to as Seo hell who engages in flyting with Satan and tells him to leave her dwelling (Old English ut of mynre onwununge). Regarding Seo Hell in the Old English Gospel of Nicodemus, Michael Bell states that "her vivid personification in a dramatically excellent scene suggests that her gender is more than grammatical, and invites comparison with the Old Norse underworld goddess Hel and the Frau Holle of German folklore, to say nothing of underworld goddesses in other cultures" yet adds that "the possibility that these genders are merely grammatical is strengthened by the fact that an Old Norse version of Nicodemus, possibly translated under English influence, personifies Hell in the neutral (Old Norse þat helvíti)."[37]

Bartholomeus saga postola

The Old Norse Bartholomeus saga postola, an account of the life of Saint Bartholomew dating from the 13th century, mentions a "Queen Hel." In the story, a devil is hiding within a pagan idol, and bound by Bartholomew's spiritual powers to acknowledge himself and confess, the devil refers to Jesus as the one which "made war on Hel our queen" (Old Norse heriaði a Hel drottning vara). "Queen Hel" is not mentioned elsewhere in the saga.[38]

Michael Bell says that while Hel "might at first appear to be identical with the well-known pagan goddess of the Norse underworld" as described in chapter 34 of Gylfaginning, "in the combined light of the Old English and Old Norse versions of Nicodemus she casts quite a different a shadow," and that in Bartholomeus saga postola "she is clearly the queen of the Christian, not pagan, underworld."[39]

Origins and development

Jacob Grimm described Hel as an example of a "half-goddess": "one who cannot be shown to be either wife or daughter of a god, and who stands in a dependent relation to higher divinities", and argued that "half-goddesses" stand higher than "half-gods" in Germanic mythology.[40] Grimm regarded Hel (whom he refers to here as Halja, the theorized Proto-Germanic form of the term) as essentially an "image of a greedy, unrestoring, female deity" and theorized that "the higher we are allowed to penetrate into our antiquities, the less hellish and more godlike may Halja appear". He compared her role, her black color, and her name to "the Indian Bhavani, who travels about and bathes like Nerthus and Holda, but is likewise called Kali or Mahakali, the great black goddess" and concluded that "Halja is one of the oldest and commonest conceptions of our heathenism".[41] He theorized that the Helhest, a three-legged horse that in Danish folklore roams the countryside "as a harbinger of plague and pestilence", was originally the steed of the goddess Hel, and that on this steed Hel roamed the land "picking up the dead that were her due". He also says that a wagon was once ascribed to Hel.[42]

In her 1948 work on death in Norse mythology and religion, The Road to Hel, Hilda Ellis Davidson argued that the description of Hel as a goddess in surviving sources appeared to be literary personification, the word hel generally being "used simply to signify death or the grave", which she states "naturally lends itself to personification by poets". While noting that "whether this personification has originally been based on a belief in a goddess of death called Hel [was] another question", she stated that she did not believe the surviving sources gave any reason to believe so, while they included various other examples of "supernatural women" who "seem to have been closely connected with the world of death, and were pictured as welcoming dead warriors". She suggested that the depiction of Hel "as a goddess" in Gylfaginning "might well owe something to these".[43]

In a later work (1998), Davidson wrote that the description of Hel found in chapter 33 of Gylfaginning "hardly suggests a goddess", but that "in the account of Hermod's ride to Hel later in Gylfaginning (49)", Hel "[speaks] with authority as ruler of the underworld" and that from her realm "gifts are sent back to Frigg and Fulla by Balder's wife Nanna as from a friendly kingdom". She posited that Snorri may have "earlier turned the goddess of death into an allegorical figure, just as he made Hel, the underworld of shades, a place 'where wicked men go,' like the Christian Hell (Gylfaginning 3)". She then, like Grimm, compared Hel to Kali:

On the other hand, a goddess of death who represents the horrors of slaughter and decay is something well known elsewhere; the figure of Kali in India is an outstanding example. Like Snorri's Hel, she is terrifying to in appearance, black or dark in colour, usually naked, adorned with severed heads or arms or the corpses of children, her lips smeared with blood. She haunts the battlefield or cremation ground and squats on corpses. Yet for all this she is "the recipient of ardent devotion from countless devotees who approach her as their mother" [...].[44]

Davidson further compared Hel to early attestations of the Irish goddesses Badb (described in The Destruction of Da Choca's Hostel as dark in color, with a large mouth, wearing a dusky mantle, and with gray hair falling over her shoulders, or, alternatively, "as a red figure on the edge of the ford, washing the chariot of a king doomed to die") and the Morrígan. She concluded that, in these examples, "here we have the fierce destructive side of death, with a strong emphasis on its physical horrors, so perhaps we should not assume that the gruesome figure of Hel is wholly Snorri's literary invention."[45]

John Lindow stated that most details about Hel, as a figure, are not found outside of Snorri's writing in Gylfaginning, and that when older skaldic poetry "says that people are 'in' rather than 'with' Hel, we are clearly dealing with a place rather than a person, and this is assumed to be the older conception". He theorizes that the noun and place Hel likely originally simply meant "grave", and that "the personification came later".[46] Lindow also drew a parallel between the personified Hel's banishment to the underworld and the binding of Fenrir as part of a recurring theme of the bound monster, where an enemy of the gods is bound but destined to break free at Ragnarok.[47] Rudolf Simek similarly stated that the figure of Hel is "probably a very late personification of the underworld Hel", that "on the whole nothing speaks in favour of there being a belief in Hel in pre-Christian times", and noted that "the first scriptures using the goddess Hel are found at the end of the 10th and in the 11th centuries". He characterized the allegorical description of Hel's house in Gylfaginning as "clearly ... in the Christian tradition".[48] However, elsewhere in the same work, Simek cites an argument made by Karl Hauck that one of three figures appearing together on Migration Period B-bracteates is to be interpreted as Hel.[49]

As a given name

In January 2017, the Icelandic Naming Committee ruled that parents could not name their child Hel "on the grounds that the name would cause the child significant distress and trouble as it grows up".[50][51]

In popular culture

Hel is one of the playable gods in the third-person multiplayer online battle arena game Smite and was one of the original 17 gods.[52] Hel is also featured in Ensemble Studios' 2002 real-time strategy game Age of Mythology, where she is one of 12 gods Norse players can choose to worship.[53][54]

See also

- Death (personification)

- Hela (comics), a Marvel comics supervillain based on the Norse being Hel

- Rán, a Norse goddess who oversees those who have drowned

- Gefjon, a Norse goddess who oversees those who die as virgins

- Freyja, a Norse goddess who oversees a portion of the dead in her afterlife field, Fólkvangr

- Odin, a Norse god who oversees a portion of the dead in his afterlife hall, Valhalla

- Helreginn, a jötunn whose name means "ruler over Hel"

- Helen of Troy, a Greek figure of divine heritage, eventually worshipped as goddess

- Hell, abode of the dead in various cultures

Notes

- Orel 2003, pp. 156, 168.

- Kroonen 2013, pp. 204, 218.

- Kroonen 2013, p. 204.

- Orel 2003, pp. 155–156.

- "Dictionary of Old English". University of Toronto. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- Scardigli, Piergiuseppe, Die Goten: Sprache und Kultur (1973) pp. 70–71.

- Lehmann, Winfred, A Gothic Etymological Dictionary (1986)

- Orel 2003, pp. 156, 464.

- This is highlighted in Watkins (2000:38).

- Larrington (1999:9).

- Larrington (1999:56).

- Larrington (1999:61).

- Larrington (1999:225 and 232).

- Larrington (1999:243).

- Larrington (1999:240 and notes).

- Dronke (1969:164).

- Faulkes (1995:26–27).

- Orchard (1997:79).

- Faulkes (1995:27).

- Faulkes (1995:49–50).

- Byock (2005:68).

- Byock (2005:69).

- Faulkes (1995:54).

- Faulkes (1995:74).

- Faulkes (1995:76).

- Faulkes (1995:123).

- Hollander (2007:20).

- Hollander (2007:46).

- Hollander (2007:47).

- Hollander (2007:20–21).

- Hollander (2007:638).

- Scudder (2001:159).

- Fisher (1999:I 75).

- Davidson (1999:II 356); Grimm (2004:314).

- Pesch (2002:67).

- Simek (2007:44); Pesch (2002:70); Bonnetain (2006:327).

- Bell (1983:263).

- Bell (1983:263–264).

- Bell (1983:265).

- Grimm (1882:397).

- Grimm (1882:315).

- Grimm (1882:314).

- Ellis (1968:84).

- Davidson (1998:178) quoting 'the recipient ...' from Kinsley (1989:116).

- Davidson (1998:179).

- Lindow (1997:172).

- Lindow (2001:82–83).

- Simek (2007:138).

- Simek (2007:44).

- "Naming committee stops parents from naming daughter after goddess of the underworld". Iceland Magazine. 10 January 2017. Archived from the original on 27 November 2019. Retrieved 11 January 2017. Cf. "Not allowed to name after Nordic goddess Hel". Iceland Monitor. 9 January 2017. Archived from the original on 18 December 2018. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- "Mál nr. 98/2016 Úrskurður 6. janúar 2017" Archived 5 July 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Mannanafnanefnd, 6 January 2017

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 31 July 2021. Retrieved 1 August 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "The Minor Gods: Norse – Age of Mythology Wiki Guide – IGN". Archived from the original on 1 August 2021. Retrieved 1 August 2021.

- "Age of Mythology".

References

- Bell, Michael (1983). "Hel Our Queen: An Old Norse Analogue to an Old English Female Hell" as collected in The Harvard Theological Review, Vol. 76, No. 2 (April 1983), pages 263–268. Cambridge University Press.

- Bonnetain, Yvonne S. (2006). "Potentialities of Loki" in Old Norse Religion in Long Term Perspectives edited by A. Andren, pp. 326–330. Nordic Academic Press. ISBN 91-89116-81-X

- Byock, Jesse (Trans.) (2005). The Prose Edda. Penguin Classics. ISBN 0-14-044755-5

- Davidson, Hilda Ellis (commentary), Peter Fisher (Trans.) 1999. Saxo Grammaticus: The History of the Danes, Books I-IX: I. English Text; II. Commentary. D. S. Brewer. ISBN 0-85991-502-6

- Davidson, Hilda Ellis (2002 [1998]). Roles of the Northern Goddess. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-13611-3

- Dronke, Ursula (1969). The Poetic Edda 1: Heroic poems. Clarendon Press

- Ellis, Hilda Roderick (1968). The Road to Hel: A Study of the Conception of the Dead in Old Norse Literature. Greenwood Press Publishers.

- Faulkes, Anthony, trans. (1987). Edda (1995 ed.). Everyman. ISBN 0-460-87616-3.

- Grimm, Jacob (James Steven Stallybrass Trans.) (1882). Teutonic Mythology: Translated from the Fourth Edition with Notes and Appendix Vol. I. London: George Bell and Sons.

- Grimm, Jacob (2004). Teutonic Mythology, vol. IV. Courier Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-43546-6

- Hollander, Lee Milton. (Trans.) (2007). Heimskringla: History of the Kings of Norway Archived 26 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine. University of Texas Press ISBN 978-0-292-73061-8

- Kinsley, D. (1989). The Goddesses' Mirror: Visions of the Divine from East to West Archived 17 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine. State University of New York Press. ISBN 0-88706-835-9

- Kroonen, Guus (2013). Etymological Dictionary of Proto-Germanic. Brill. ISBN 9789004183407. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- Larrington, Carolyne (Trans.) (1999). The Poetic Edda. Oxford World's Classics. ISBN 0-19-283946-2

- Orchard, Andy (1997). Dictionary of Norse Myth and Legend. Cassell. ISBN 978-0-304-34520-5.

- Orel, Vladimir E. (2003). A Handbook of Germanic Etymology. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-12875-0. Archived from the original on 29 July 2020. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- Pesch, Alexandra (2002). "Frauen und Brakteaten – eine Skizze". In Rudolf Simek; Wilhelm Heizmann (eds.). Mythological Women. Vienna: Verlag Fassbaender. pp. 33–80. ISBN 3-900538-73-5.

- Scudder, Bernard (Trans.) (2001). Egils saga. Penguin Group. ISBN 978-0-141-00003-9

- Simek, Rudolf (1996). Dictionary of Northern Mythology. D.S. Brewer. ISBN 978-0-85991-513-7. Archived from the original on 14 June 2020. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- Watkins, Calvert (2000). The American Heritage Dictionary of Indo-European Roots. Houghton Mifflin Company. ISBN 0-395-98610-9

External links

- MyNDIR (My Norse Digital Image Repository)—Illustrations of Hel from manuscripts and early print books. Clicking on the thumbnail will give the full image and information concerning it.