Heinz Kiwitz

Heinz Kiwitz (September 4, 1910 – 1938) was a German artist. His woodcuts were in the German Expressionist style. An anti-fascist, he was arrested following the Nazis' seizure of power. He survived imprisonment in Kemna and Börgermoor concentration camps and was released in 1934. He went into exile in 1937, first living in Denmark, then in France, where he again began to fight Nazism. In 1938, he went to Spain to fight in the Spanish Civil War, where he apparently perished.

Heinz Kiwitz | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | September 4, 1910 Duisburg, Germany |

| Died | 1938 Spain |

| Nationality | German |

| Education | Folkwangschule |

| Known for | woodcut illustration |

| Movement | German Expressionism |

| Website | www |

Early years

Kiwitz was born the son of a book printer and was exposed to the graphic arts from an early age.[1] He had an older sister, Änne, and a younger sister, Gertrude, called Trudel.[2] From early on, he loved to draw, but was not good in math. At the age of 10, he drew his older sister's art assignments and she received top grades. When he was 17 and stood 1.92 meters (6.3 ft), he joined a boxing club and trained at home, causing the furniture to shake when he jumped rope inside.[2]

In 1927, he began studying art with Karl Rössing at the Folkwang University of the Arts in Essen.[1] His long-time friend, Günther Strupp also attended the school[3] and was a student of Rössing's. He was a member of the Association of Revolutionary Visual Artists during this period.[4]

Work and anti-fascist resistance

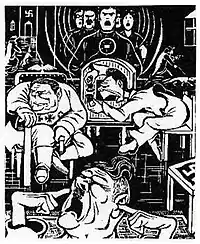

In art school, he preferred to create wood engravings, but after finishing, Kiwitz began working more with woodcuts, which entailed a process more suited to his temperament.[5] He and Strupp went to Cologne for a few months and later, he went to Berlin to pursue work and further study. In April 1932, his woodcut illustrations for a satirical poem by Erich Weinert were published along with the poem in Magazin für Alle.[6] He also made a woodcut decrying the Nazi book burnings and one that features caricatures of Hitler, Goebbels and Göring (see illustration).[7] In early 1933, after the Nazis seized power, Kiwitz' studio was ransacked by the Sturmabteilung (SA) and he left Berlin, returning to his parents' home.[1] He also visited his girlfriend, who as a Communist and political enemy of the Nazis, had been arrested and thrown in prison.[1]

Shortly after, in summer 1933, he also was arrested and thrown in Kemna concentration camp[1] for "antifascist activity" and having produced "work critical of society". From Kemna, he was later transferred to Börgermoor concentration camp. After his release in June 1934, he sought to protect himself from further arrest by destroying the majority of his political artwork and confining his illustrations to literary themes.[1] He described himself as a "Nazi-coerced-towards-harmless-themes-political-journalist."[5] He returned to Berlin in 1935, where he worked for the publisher Ernst Rowohlt. He designed covers for books by William Faulkner and created illustrations for a novel by Hans Fallada; he also made woodcuts illustrating Don Quixote,[1][5] and Eduard Mörike's "Die Historie von der schönen Lau", among others.[8]

As a socialist, Kiwitz saw little future and only danger for himself in Germany. In 1937, with help from Rowohlt, he managed to flee to Copenhagen, Denmark, where he met Bertolt Brecht.[1] His residence permit, just three months, was not renewed, forcing him to leave. He then went to Paris,[9] where he again began to fight fascism. An organization of exiled German artists, the Union des Artistes Allemands Libres, was founded in autumn 1937[10] and Kiwitz became an early member.[note 1] The group organized an exhibit called "Five Years of Hitler Dictatorship", (Fünf Jahre Hitler-Diktatur) held at a local union hall.[1] He worked on the exhibition[11] and contributed to the exhibition brochure, Cinq Ans de Dictateure Hitlerienne, cutting out a piece of linoleum flooring from under his bed and making linocuts depicting torture, courtroom trials and forced labor in the Third Reich. Also while in Paris, he made a woodcut about the Bombing of Guernica and other alleged war crimes.[7]

Letters to his parents during this time do not mention his political activities, but a request for a sum of money (10 Reichsmark) indicates his financial status was precarious.[1] Kiwitz worked for the emigrant press while in Paris and on August 27, 1937, published his Absage eines deutschen Künstlers an Hitler ("Renunciation of Hitler by a German Artist") in a Paris newspaper. In 1938, he went to Spain to fight against Francisco Franco in the International Brigades. He is known to have participated in the Battle of the Ebro, but then all trace of him vanishes. He is presumed to have been killed there.[12]

Open letter to Hitler

The text of Kiwitz' 1937 open letter of renunciation to Hitler printed below was printed in a German-language exile newspaper in Paris.[13][note 2]

A young German artist, Heinz Kiwitz, presents to the public the following findings:

The Berlin art exhibition at the Haus der Kunst on Königsplatz was proclaimed by the Nazi Party and the "Reich Commissioner for Artistic Design" Schweitzer – Mjölnir as paving the way.

Without asking me or obtaining my consent, woodcuts of mine were put on exhibit. A portion of the coordinated Berlin press dedicated much space to me in the arts section, which now, instead of offering art criticism, treads lock-step. They have held me up as one of the most important artists of the "new Germany".

In addition, is this fact: I went into exile from Germany in January 1937. I do not wish to be recognized by those who rule Germany today, who lock up art in military barracks and have it kicked into shape by combat boots. Everything in me rebels against the violent abuse of art which is to mask the hideous face of war.

If of necessity the fascist newspapers are forced to admit that I am an artist of the people, it is not a compliment for me, rather it is to be judged as an admission of the bankruptcy of little Goebbels' art factories. For I myself deliberately and always have repudiated the un-German destruction of art, which chases and hunts the true artist abroad, declares every house painter a genius if only he has had the Party membership in his pocket long enough and kowtows before the dictator. It is precisely this adulteration from above from which the authentic, great German art arose as protest, from Riemenschneider to Schiller's Don Carlos to Lehmbruck and Barlach. My populism makes me belong with Nolde and Barlach, against whom the Schwarze Korps is leading a brutal campaign, whose works they remove from galleries and whose exhibitions were closed by the Gestapo because they unswervingly carry on the tradition in the path of Albrecht Dürer and Matthias Grünewald.

At the cradle of German art stood a sculptor, Tilmann Riemenschneider, who, because his heart beat with the hunted, rebelling peasants, was so harmed in torture by the rich tyrants, that by the end of his life, he could no longer wield a chisel.

The German artist Wilhelm Lehmbruck, in 1914, as a socialist, refused the same militarists his service in war, who today have declared total war on free art.

Guernica, concentration camps and war against religion – what can German art create with this dance of death of human culture, other than to swing the scourge against this forced march into barbarism? Desperately, they search their Party card file for a small talent and cannot find it. They are prepared to pay any price, believe they can buy Serious Geniuses for money just like they acquire mansions and cars. True art grows from love of life, human kindness and fruitful unfoldment. Art always goes against tyranny and with liberty. Death, hate and deprivation are the negative fundamental values of fascism. They have proclaimed the Führerprinzip and eradicated freedom of thought, declared the people to be "disciple" minors without rights, tributary masses.

But German art grows out of the people, with the people, for the people, and against coercion, amateurish capriciousness and dictators. The genuine artist only wants to be recognized by that Germany which the greatest German artists long for, a true democratic people's republic of Germany. Because for us, that means freedom of thought, creative freedom, artistic freedom.

Heinz Kiwitz

Pariser Tageszeitung, August 27, 1937

Recognition

Kiwitz is grouped with Wilhelm Lehmbruck and August Kraus as one of the most important 20th-century artists from Duisburg.[12] In 1962, the Städtisches Kunstmuseum (City Art Museum) in Duisburg had an exhibit of Kiwitz' work and in 1992, the Lehmbruck Museum in Duisburg had an exhibit called "Heinz Kiwitz Druckgraphik".[14] From April 1983 to April 1984, there was a traveling exhibit of Kiwitz' work. Called "Heinz Kiwitz : Holzschnitte, Linolschnitte und Zeichnungen", the exhibit started in Lüdenscheid, then moved to Telgte, then to the Städtisches Museum in Gelsenkirchen and then finished at the Galerie im Theater in Gütersloh.[15] There is a street in Duisburg named Heinz-Kiwitz-Strasse[16] in his honor in 2005. In 2010, in honor of the 100th anniversary of his birth, the Brennender Dornbusch Foundation organized an exhibit of Kiwitz' work at the Liebfrauenkirche in Duisburg.[8] His younger sister, Trudel Siepmann, attended the opening.[8]

Works (selected)

- Cover for German edition: William Faulkner, Light in August, Rowohlt Verlag Berlin (1935)

- Cover and illustrations: Hans Fallada, Märchen vom Stadtschreiber, der aufs Land flog, Rowohlt Verlag Berlin (1935)

- Enaks Geschichten, a story in woodcuts, foreword by Hans Fallada, Rowohlt Verlag Berlin (1936)

- Cover illustration for German edition: William Faulkner, Pylon (German: Wendemarke), Verlag Berlin (1936)

Notes

- Other members of the Union, called Freier Künstlerbund in German, included Max Ernst, Otto Freundlich, Hans Hartung, Anton Räderscheid, Heinz Lohmar and Gert Wollheim.[7]

- His letter mistakenly identifies the Haus der Kunst as being in Berlin. The exhibit was in Munich.[13]

References

- Siegfried Gnichwitz, "Heinz Kiwitz: gekämpft · vertrieben · verschollen" Archived 2012-11-20 at the Wayback Machine (PDF) Stiftung Brennender Dornbusch. Folder from an exhibition in honor of the 100th anniversary of Kiwitz' birth. Liebfrauenkirche, Duisburg (November 7 – December 5, 2010), p. 2. Retrieved February 10, 2012 (in German)

- Anne Kiwitz, "Privates" 1930 photo and reminiscence Heinz Kiwitz. Retrieved February 13, 2012 (in German)

- Kiwitz, Heinz Exil Archiv. Retrieved February 26, 2012 (in German)

- Biografie: 1927–1931 Heinz Kiwitz website. Click on list at left of frame, "Vita: Biografie" Retrieved February 11, 2012 (in German)

- Gnichwitz, p. 7 Archived 2012-11-20 at the Wayback Machine (PDF) (in German)

- Gnichwitz, p. 3 Archived 2012-11-20 at the Wayback Machine (PDF) (in German)

- Gnichwitz, pp. 4–5 Archived 2012-11-20 at the Wayback Machine (PDF) (in German)

- "Gekämpft, vertrieben, verschollen" Rheinische Post (November 6, 2010). Retrieved February 10, 2012 (in German)

- Hélène Roussel, "Les Peintres Allemands Émigrés en France et L'Union des Artistes Libres" in: Gilbert Badia, Jean Baptiste Joly, Jean Philippe Mathieu, Jacque Omnes, Jean Michel Palmier, Hélène Roussel, Les Bannis de Hitler, Études et Documentation Internationales / Presses Universitaires de Vincennes, Paris (1984), p. 289. ISBN 2-85139-074-0 (EDI), 2-90 3981-19-1 (PUV). Retrieved February 27, 2012 (in French)

- Jean Michel Palmier, Weimar in Exile: The Antifascist Emigration in Europe and America Translated by David Fernbach. Verso (2006), p. 216. ISBN 1-84467-068-6 Retrieved February 13, 2012

- Hélène Roussel (1984), p. 295 (in French)

- Thomas Becker, "Willkommen im Club" Der Westen (October 7, 2008). Retrieved February 11, 2012 (in German)

- Heinz Kiwitz, "Absage an Hitler" and woodcuts from Paris (scroll down) reprinted from Pariser Tageszeitung, Vol. 2, No. 440 (August 27, 1937). Retrieved February 11, 2012 (in German)

- Literatur (click on menu at left) Heinz Kiwitz. Retrieved February 13, 2012 (in German)

- Catalogue WorldCat. Städtische Galerie Lüdenscheid (1983). Retrieved February 13, 2012

- Stadtplan – Duisburg – Heinz-Kiwitz-Str Stadtplan Duisburg. Retrieved February 10, 2012 (in German)

Further reading

- Heinz Kiwitz Zeichnungen und Holzschnitte, Catalogue, Städtisches Kunstmuseum, Duisburg (1962) (in German)

- Paul Bender, Heinz Kiwitz – Holzschnitte, Carl Lange Verlag, Duisburg (1963) (in German)

- Ulrich Krempel and B. Hess, "Was war denn da schon zum Lachen? Heinz Kiwitz 1910-38", in: Sammlung-Jahrbuch 2 für antifaschistische Literatur und Kunst, Frankfurt am Main (1979)

- Martina Ewers-Schulz, Heinz Kiwitz Druckgraphik. Catalogue, Wilhelm Lehmbruck Museum, Duisburg, (1992) (in German)

External links

- Heinz Kiwitz official website (in German)