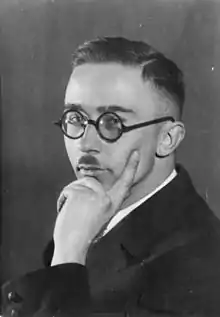

Heinrich Himmler

Heinrich Luitpold Himmler (German: [ˈhaɪnʁɪç ˈluːɪtpɔlt ˈhɪmlɐ] ⓘ; 7 October 1900 – 23 May 1945) was the Reichsführer of the Schutzstaffel (Protection Squadron; SS), a leading member of the Nazi Party of Germany, and one of the most powerful men in Nazi Germany, primarily known for being a main architect of the Holocaust.

Heinrich Himmler | |

|---|---|

Official portrait, 1942 | |

| 4th Reichsführer-SS | |

| In office 6 January 1929 – 29 April 1945 | |

| Deputy | Reinhard Heydrich |

| Preceded by | Erhard Heiden |

| Succeeded by | Karl Hanke |

| Chief of the German Police | |

| In office 17 June 1936 – 29 April 1945 | |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | Karl Hanke |

| Reichsminister of the Interior | |

| In office 24 August 1943 – 29 April 1945 | |

| Chancellor | Adolf Hitler |

| Preceded by | Wilhelm Frick |

| Succeeded by | Paul Giesler |

| Commander of the Replacement Army | |

| In office 21 July 1944 – 29 April 1945 | |

| Preceded by | Friedrich Fromm |

| Succeeded by | Office abolished |

| Additional positions | |

| January—March 1945 | Commander of Army Group Vistula |

| 1944–1945 | Commander of Army Group Upper Rhine |

| 1942–1943 | Acting Director of the Reich Security Main Office |

| 1939–1945 | Reich Commissioner for the Consolidation of German Nationhood |

| 1933–1945 | Member of the Prussian State Council |

| 1933–1945 | Reichsleiter of the Nazi Party |

| 1933—1945 | Member of the Greater German Reichstag |

| 1930–1933 | Member of the Reichstag |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Heinrich Luitpold Himmler 7 October 1900[1] Munich, Kingdom of Bavaria, German Empire |

| Died | 23 May 1945 (aged 44) Lüneburg, Germany |

| Cause of death | Suicide by cyanide poisoning |

| Political party | Nazi Party (1923–1945) |

| Other political affiliations | Bavarian People's Party (1919–1923) |

| Spouse | |

| Domestic partner | Hedwig Potthast (1939–1944) |

| Children |

|

| Relatives |

|

| Education | Technical University of Munich |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1917–1918 (Army) 1925–1945 (SS) |

| Rank | |

| Unit | 11th Bavarian Infantry Regiment |

| Commands | Army Group Upper Rhine Army Group Vistula Replacement (Home) Army |

| Battles/wars | World War II |

As a member of a reserve battalion during the First World War, Himmler did not see active service or combat. Having joined the Nazi Party in 1923 and the SS in 1925, he was appointed Reichsführer-SS by Adolf Hitler in 1929. Over the next sixteen years, Himmler developed the SS from a 290-man battalion into a million-strong paramilitary group. He was known for good organisational skills and for selecting highly competent subordinates, such as Reinhard Heydrich in 1931. From 1943 onwards, he was both Chief of the Kriminalpolizei (Criminal Police) and Minister of the Interior, overseeing all internal and external police and security forces, including the Gestapo (Secret State Police). He also controlled the Waffen-SS, the military branch of the SS.

Himmler's interest in occultism and Völkisch topics influenced the development of the racial policy of Nazi Germany; he also incorporated esoteric symbolism and rituals into the SS. He was the principal overseer of Nazi Germany's genocidal programs, forming the Einsatzgruppen and administering extermination camps. In this capacity, Himmler directed the killing of some six million Jews, between 200,000 and 500,000 Romani people, and other victims. A day before the launch of Operation Barbarossa, Himmler commissioned the drafting of Generalplan Ost, which was approved by Hitler in May 1942. The total number of civilians killed by the Nazi regime is estimated to be between 11 to 14 million people, most of whom were Polish and Soviet citizens.

Late in the Second World War, Hitler briefly appointed Himmler as military commander and later Commander of the Replacement (Home) Army and General Plenipotentiary for the administration of the entire Third Reich (Generalbevollmächtigter für die Verwaltung). Specifically, he was given command of the Army Group Upper Rhine and the Army Group Vistula. After Himmler failed to achieve his assigned objectives, Hitler replaced him in these posts. Realising the war was lost, Himmler attempted to open peace talks with the western Allies without Hitler's knowledge, shortly before the end of the war. Hearing of this, Hitler dismissed him from all his posts in April 1945 and ordered his arrest. Himmler attempted to go into hiding but was detained and then arrested by British forces once his identity became known. While in British custody, he died by suicide on 23 May 1945.

Early life

Heinrich Luitpold Himmler was born in Munich on 7 October 1900 into a conservative middle-class Roman Catholic family. His father was Joseph Gebhard Himmler (1865–1936), a teacher, and his mother was Anna Maria Himmler (née Heyder; 1866–1941), a devout Roman Catholic. Heinrich had two brothers: Gebhard Ludwig (1898–1982) and Ernst Hermann (1905–1945).[3]

Himmler's first name, Heinrich, was that of his godfather, Prince Heinrich of Bavaria, a member of the royal family of Bavaria, who had been tutored by Gebhard Himmler.[4][5] He attended a grammar school in Landshut, where his father was deputy principal. While he did well in his schoolwork, he struggled in athletics.[6] He had poor health, suffering from lifelong stomach complaints and other ailments. In his youth he trained daily with weights and exercised to become stronger. Other boys at the school later remembered him as studious and awkward in social situations.[7]

Himmler's diary, which he kept intermittently from the age of 10, shows that he took a keen interest in current events, dueling, and "the serious discussion of religion and sex".[8][9] In 1915, he began training with the Landshut Cadet Corps. His father used his connections with the royal family to get Himmler accepted as an officer candidate, and he enlisted with the reserve battalion of the 11th Bavarian Regiment in December 1917. His brother, Gebhard, served on the western front and saw combat, receiving the Iron Cross and eventually being promoted to lieutenant. In November 1918, while Himmler was still in training, the war ended with Germany's defeat, denying him the opportunity to become an officer or see combat. After his discharge on 18 December, he returned to Landshut.[10] After the war, Himmler completed his grammar-school education. From 1919 to 1922, he studied agriculture at the Munich Technische Hochschule (now Technical University Munich) [11] following a brief apprenticeship on a farm and a subsequent illness.[12][13]

Although many regulations that discriminated against non-Christians—including Jews and other minority groups—had been eliminated during the unification of Germany in 1871, antisemitism continued to exist and thrive in Germany and other parts of Europe.[14] Himmler was antisemitic by the time he went to university, but not exceptionally so; students at his school would avoid their Jewish classmates.[15] He remained a devout Catholic while a student and spent most of his leisure time with members of his fencing fraternity, the "League of Apollo", the president of which was Jewish. Himmler maintained a polite demeanor with him and with other Jewish members of the fraternity, in spite of his growing antisemitism.[16][17] During his second year at university, Himmler redoubled his attempts to pursue a military career. Although he was not successful, he was able to extend his involvement in the paramilitary scene in Munich. It was at this time that he first met Ernst Röhm, an early member of the Nazi Party and co-founder of the Sturmabteilung ("Storm Battalion"; SA).[18][19] Himmler admired Röhm because he was a decorated combat soldier, and at his suggestion Himmler joined his antisemitic nationalist group, the Bund Reichskriegsflagge (Imperial War Flag Society).[20]

In 1922, Himmler became more interested in the "Jewish question", with his diary entries containing an increasing number of antisemitic remarks and recording a number of discussions about Jews with his classmates. His reading lists, as recorded in his diary, were dominated by antisemitic pamphlets, German myths, and occult tracts.[21] After the murder of Foreign Minister Walther Rathenau on 24 June, Himmler's political views veered towards the radical right, and he took part in demonstrations against the Treaty of Versailles. Hyperinflation was raging, and his parents could no longer afford to educate all three sons. Disappointed by his failure to make a career in the military and his parents' inability to finance his doctoral studies, he was forced to take a low-paying office job after obtaining his agricultural diploma. He remained in this position until September 1923.[22][23]

Nazi activist

Himmler joined the Nazi Party on 1 August 1923,[24] receiving party number 14303.[25][26] As a member of Röhm's paramilitary unit, Himmler was involved in the Beer Hall Putsch—an unsuccessful attempt by Hitler and the Nazi Party to seize power in Munich. This event would set Himmler on a life of politics. He was questioned by the police about his role in the putsch but was not charged because of insufficient evidence. However, he lost his job, was unable to find employment as a farm manager, and had to move in with his parents in Munich. Frustrated by these failures, he became ever more irritable, aggressive, and opinionated, alienating both friends and family members.[27][28]

In 1923–24, Himmler, while searching for a world view, came to abandon Catholicism and focused on the occult and in antisemitism. Germanic mythology, reinforced by occult ideas, became a religion for him. Himmler found the Nazi Party appealing because its political positions agreed with his own views. Initially, he was not swept up by Hitler's charisma or the cult of Führer worship. However, as he learned more about Hitler through his reading, he began to regard him as a useful face of the party,[29][30] and he later admired and even worshipped him.[31] To consolidate and advance his own position in the Nazi Party, Himmler took advantage of the disarray in the party following Hitler's arrest in the wake of the Beer Hall Putsch.[31] From mid-1924 he worked under Gregor Strasser as a party secretary and propaganda assistant. Travelling all over Bavaria agitating for the party, he gave speeches and distributed literature. Placed in charge of the party office in Lower Bavaria by Strasser from late 1924, he was responsible for integrating the area's membership with the Nazi Party under Hitler when the party was re-founded in February 1925.[32][33]

That same year, he joined the Schutzstaffel (SS) as an SS-Führer (SS-Leader); his SS number was 168.[26] The SS, initially part of the much larger SA, was formed in 1923 for Hitler's personal protection and was re-formed in 1925 as an elite unit of the SA.[34] Himmler's first leadership position in the SS was that of SS-Gauführer (district leader) in Lower Bavaria from 1926. Strasser appointed Himmler deputy propaganda chief in January 1927. As was typical in the Nazi Party, he had considerable freedom of action in his post, which increased over time. He began to collect statistics on the number of Jews, Freemasons, and enemies of the party, and following his strong need for control, he developed an elaborate bureaucracy.[35][36] In September 1927, Himmler told Hitler of his vision to transform the SS into a loyal, powerful, racially pure elite unit. Convinced that Himmler was the man for the job, Hitler appointed him Deputy Reichsführer-SS, with the rank of SS-Oberführer.[37]

Around this time, Himmler joined the Artaman League, a Völkisch youth group. There he met Rudolf Höss, who was later commandant of Auschwitz concentration camp, and Walther Darré, whose book The Peasantry as the Life Source of the Nordic Race caught Hitler's attention, leading to his later appointment as Reich Minister of Food and Agriculture. Darré was a firm believer in the superiority of the Nordic race, and his philosophy was a major influence on Himmler.[34][38][39]

Rise in the SS

Upon the resignation of SS commander Erhard Heiden in January 1929, Himmler assumed the position of Reichsführer-SS with Hitler's approval;[37][40][lower-alpha 1] he still carried out his duties at propaganda headquarters. One of his first responsibilities was to organise SS participants at the Nuremberg Rally that September.[41] Over the next year, Himmler grew the SS from a force of about 290 men to about 3,000. By 1930 Himmler had persuaded Hitler to run the SS as a separate organisation, although it was officially still subordinate to the SA.[42][43]

To gain political power, the Nazi Party took advantage of the economic downturn during the Great Depression. The coalition government of the Weimar Republic was unable to improve the economy, so many voters turned to the political extreme, which included the Nazi Party.[44] Hitler used populist rhetoric, including blaming scapegoats—particularly the Jews—for the economic hardships.[45] In September 1930, Himmler was first elected as a deputy to the Reichstag.[46] In the 1932 election, the Nazis won 37.3 percent of the vote and 230 seats in the Reichstag.[47] Hitler was appointed Chancellor of Germany by President Paul von Hindenburg on 30 January 1933, heading a short-lived coalition of his Nazis and the German National People's Party. The new cabinet initially included only three members of the Nazi Party: Hitler, Hermann Göring as minister without portfolio and Minister of the Interior for Prussia, and Wilhelm Frick as Reich Interior Minister.[48][49] Less than a month later, the Reichstag building was set on fire. Hitler took advantage of this event, forcing Hindenburg to sign the Reichstag Fire Decree, which suspended basic rights and allowed detention without trial.[50] The Enabling Act, passed by the Reichstag on 23 March 1933, gave the Cabinet—in practice, Hitler—full legislative powers, and the country became a de facto dictatorship.[51] On 1 August 1934, Hitler's cabinet passed a law which stipulated that upon Hindenburg's death, the office of president would be abolished and its powers merged with those of the chancellor. Hindenburg died the next morning, and Hitler became both head of state and head of government under the title Führer und Reichskanzler (leader and chancellor).[52]

The Nazi Party's rise to power provided Himmler and the SS an unfettered opportunity to thrive. By 1933, the SS numbered 52,000 members.[53] Strict membership requirements ensured that all members were of Hitler's Aryan Herrenvolk ("Aryan master race"). Applicants were vetted for Nordic qualities—in Himmler's words, "like a nursery gardener trying to reproduce a good old strain which has been adulterated and debased; we started from the principles of plant selection and then proceeded quite unashamedly to weed out the men whom we did not think we could use for the build-up of the SS."[54] Few dared mention that by his own standards, Himmler did not meet his own ideals.[55]

Himmler's organised, bookish intellect served him well as he began setting up different SS departments. In 1931 he appointed Reinhard Heydrich chief of the new Ic Service (intelligence service), which was renamed the Sicherheitsdienst (SD: Security Service) in 1932. He later officially appointed Heydrich his deputy.[56] The two men had a good working relationship and a mutual respect.[57] In 1933, they began to remove the SS from SA control. Along with Interior Minister Frick, they hoped to create a unified German police force. In March 1933, Reich Governor of Bavaria Franz Ritter von Epp appointed Himmler chief of the Munich Police. Himmler appointed Heydrich commander of Department IV, the political police.[58] Thereafter, Himmler and Heydrich took over the political police of state after state; soon only Prussia was controlled by Göring.[59] Effective 1 January 1933, Hitler promoted Himmler to the rank of SS-Obergruppenführer, equal in rank to the senior SA commanders.[60] On 2 June Himmler, along with the heads of the other two Nazi paramilitary organizations, the SA and the Hitler Youth, was named a Reichsleiter, the second highest political rank in the Nazi Party. On 10 July, he was named to the Prussian State Council.[46] On 2 October 1933, he became a founding member of Hans Frank's Academy for German Law at its inaugural meeting.[61]

Himmler further established the SS Race and Settlement Main Office (Rasse- und Siedlungshauptamt or RuSHA). He appointed Darré as its first chief, with the rank of SS-Gruppenführer. The department implemented racial policies and monitored the "racial integrity" of the SS membership.[62] SS men were carefully vetted for their racial background. On 31 December 1931, Himmler introduced the "marriage order", which required SS men wishing to marry to produce family trees proving that both families were of Aryan descent to 1800.[63] If any non-Aryan forebears were found in either family tree during the racial investigation, the person concerned was excluded from the SS.[64] Each man was issued a Sippenbuch, a genealogical record detailing his genetic history.[65] Himmler expected that each SS marriage should produce at least four children, thus creating a pool of genetically superior prospective SS members. The programme had disappointing results; less than 40 per cent of SS men married and each produced only about one child.[66]

In March 1933, less than three months after the Nazis came to power, Himmler set up the first official concentration camp at Dachau.[67] Hitler had stated that he did not want it to be just another prison or detention camp. Himmler appointed Theodor Eicke, a convicted felon and ardent Nazi, to run the camp in June 1933.[68] Eicke devised a system that was used as a model for future camps throughout Germany.[38] Its features included isolation of victims from the outside world, elaborate roll calls and work details, the use of force and executions to exact obedience, and a strict disciplinary code for the guards. Uniforms were issued for prisoners and guards alike; the guards' uniforms had a special Totenkopf insignia on their collars. By the end of 1934, Himmler took control of the camps under the aegis of the SS, creating a separate division, the SS-Totenkopfverbände.[69][70]

| Part of a series on |

| Antisemitism |

|---|

|

|

|

Initially the camps housed political opponents; over time, undesirable members of German society—criminals, vagrants, deviants—were placed in the camps as well. In 1936 Himmler wrote in the pamphlet "The SS as an Anti-Bolshevist Fighting Organization" that the SS were to fight against the "Jewish-Bolshevik revolution of subhumans".[71] A Hitler decree issued in December 1937 allowed for the incarceration of anyone deemed by the regime to be an undesirable member of society.[72] This included Jews, Gypsies, communists, and those persons of any other cultural, racial, political, or religious affiliation deemed by the Nazis to be Untermensch (sub-human). Thus, the camps became a mechanism for social and racial engineering. By the outbreak of World War II in autumn 1939, there were six camps housing some 27,000 inmates. Death tolls were high.[73]

Consolidation of power

In early 1934, Hitler and other Nazi leaders became concerned that Röhm was planning a coup d'état.[74] Röhm had socialist and populist views and believed that the real revolution had not yet begun. He felt that the SA—now numbering some three million men, far dwarfing the army—should become the sole arms-bearing corps of the state, and that the army should be absorbed into the SA under his leadership. Röhm lobbied Hitler to appoint him Minister of Defence, a position held by conservative General Werner von Blomberg.[75]

Göring had created a Prussian secret police force, the Geheime Staatspolizei or Gestapo in 1933 and appointed Rudolf Diels as its head. Göring, concerned that Diels was not ruthless enough to use the Gestapo effectively to counteract the power of the SA, handed over its control to Himmler on 20 April 1934.[76] Also on that date, Hitler appointed Himmler chief of all German police outside Prussia. This was a radical departure from long-standing German practice that law enforcement was a state and local matter. Heydrich, named chief of the Gestapo by Himmler on 22 April 1934, also continued as head of the SD.[77]

Hitler decided on 21 June that Röhm and the SA leadership had to be eliminated. He sent Göring to Berlin on 29 June, to meet with Himmler and Heydrich to plan the action. Hitler took charge in Munich, where Röhm was arrested; he gave Röhm the choice to commit suicide or be shot. When Röhm refused to kill himself, he was shot dead by two SS officers. Between 85 and 200 members of the SA leadership and other political adversaries, including Gregor Strasser, were killed between 30 June and 2 July 1934 in these actions, known as the Night of the Long Knives.[78][79] With the SA thus neutralised, the SS became an independent organisation answerable only to Hitler on 20 July 1934. Himmler's title of Reichsführer-SS became the highest formal SS rank, equivalent to a field marshal in the army.[80] The SA was converted into a sports and training organisation.[81]

On 15 September 1935, Hitler presented two laws—known as the Nuremberg Laws—to the Reichstag. The laws banned marriage between non-Jewish and Jewish Germans and forbade the employment of non-Jewish women under the age of 45 in Jewish households. The laws also deprived so-called "non-Aryans" of the benefits of German citizenship.[82] These laws were among the first race-based measures instituted by the Third Reich.

Himmler and Heydrich wanted to extend the power of the SS; thus, they urged Hitler to form a national police force overseen by the SS, to guard Nazi Germany against its many enemies at the time—real and imagined.[83] Interior Minister Frick also wanted a national police force, but one controlled by him, with Kurt Daluege as his police chief.[84] Hitler left it to Himmler and Heydrich to work out the arrangements with Frick. Himmler and Heydrich had greater bargaining power, as they were allied with Frick's old enemy, Göring. Heydrich drew up a set of proposals and Himmler sent him to meet with Frick. An angry Frick then consulted with Hitler, who told him to agree to the proposals. Frick acquiesced, and on 17 June 1936 Hitler decreed the unification of all police forces in the Reich and named Himmler Chief of German Police and a State Secretary in the Ministry of the Interior.[84] In this role, Himmler was still nominally subordinate to Frick. In practice, however, the police were now effectively a division of the SS, and hence independent of Frick's control. This move gave Himmler operational control over Germany's entire detective force.[84][85] He also gained authority over all of Germany's uniformed law enforcement agencies, which were amalgamated into the new Ordnungspolizei (Orpo: "order police"), which became a branch of the SS under Daluege.[84]

Shortly thereafter, Himmler created the Kriminalpolizei (Kripo: criminal police) as an umbrella organisation for all criminal investigation agencies in Germany. The Kripo was merged with the Gestapo into the Sicherheitspolizei (SiPo: security police), under Heydrich's command.[86] In September 1939, following the outbreak of World War II, Himmler formed the SS-Reichssicherheitshauptamt (RSHA: Reich Security Main Office) to bring the SiPo (which included the Gestapo and Kripo) and the SD together under one umbrella. He again placed Heydrich in command.[87]

Under Himmler's leadership, the SS developed its own military branch, the SS-Verfügungstruppe (SS-VT), which later evolved into the Waffen-SS. Nominally under the authority of Himmler, the Waffen-SS developed a fully militarised structure of command and operations. It grew from three regiments to over 38 divisions during World War II, serving alongside the Heer (army), but never being formally part of it.[88]

In addition to his military ambitions, Himmler established the beginnings of a parallel economy under the umbrella of the SS.[89] To this end, administrator Oswald Pohl set up the Deutsche Wirtschaftsbetriebe (German Economic Enterprise) in 1940. Under the auspices of the SS Economy and Administration Head Office, this holding company owned housing corporations, factories, and publishing houses.[90] Pohl was unscrupulous and quickly exploited the companies for personal gain. In contrast, Himmler was honest in matters of money and business.[91]

In 1938, as part of his preparations for war, Hitler ended the German alliance with China and entered into an agreement with the more modern Japan. That same year, Austria was unified with Nazi Germany in the Anschluss, and the Munich Agreement gave Nazi Germany control over the Sudetenland, part of Czechoslovakia.[92] Hitler's primary motivations for war included obtaining additional Lebensraum ("living space") for the Germanic peoples, who were considered racially superior according to Nazi ideology.[93] A second goal was the elimination of those considered racially inferior, particularly the Jews and Slavs, from territories controlled by the Reich. From 1933 to 1938, hundreds of thousands of Jews emigrated to the United States, Palestine, Great Britain, and other countries. Some converted to Christianity.[94]

Anti-church struggle

According to Himmler biographer Peter Longerich, Himmler believed that a major task of the SS should be "acting as the vanguard in overcoming Christianity and restoring a 'Germanic' way of living" as part of preparations for the coming conflict between "humans and subhumans".[95] Longerich wrote that, while the Nazi movement as a whole launched itself against Jews and Communists, "by linking de-Christianisation with re-Germanization, Himmler had provided the SS with a goal and purpose all of its own".[95] Himmler was vehemently opposed to Christian sexual morality and the "principle of Christian mercy", both of which he saw as dangerous obstacles to his planned battle with "subhumans".[95] In 1937, Himmler declared:

We live in an era of the ultimate conflict with Christianity. It is part of the mission of the SS to give the German people in the next half century the non-Christian ideological foundations on which to lead and shape their lives. This task does not consist solely in overcoming an ideological opponent but must be accompanied at every step by a positive impetus: in this case that means the reconstruction of the German heritage in the widest and most comprehensive sense.[96]

In early 1937, Himmler had his personal staff work with academics to create a framework to replace Christianity within the Germanic cultural heritage. The project gave rise to the Deutschrechtliches Institut, headed by Professor Karl Eckhardt, at the University of Bonn.[97]

World War II

When Hitler and his army chiefs asked for a pretext for the invasion of Poland in 1939, Himmler, Heydrich, and Heinrich Müller masterminded and carried out a false flag project code-named Operation Himmler. German soldiers dressed in Polish uniforms undertook border skirmishes which deceptively suggested Polish aggression against Germany. The incidents were then used in Nazi propaganda to justify the invasion of Poland, the opening event of World War II.[98] At the beginning of the war against Poland, Hitler authorised the killing of Polish civilians, including Jews and ethnic Poles. The Einsatzgruppen (SS task forces) had originally been formed by Heydrich to secure government papers and offices in areas taken over by Germany before World War II.[99] Authorised by Hitler and under the direction of Himmler and Heydrich, the Einsatzgruppen units—now repurposed as death squads—followed the Heer (army) into Poland, and by the end of 1939 they had murdered some 65,000 intellectuals and other civilians. Militias and Heer units also took part in these killings.[100][101] Under Himmler's orders via the RSHA, these squads were also tasked with rounding up Jews and others for placement in ghettos and concentration camps.

Germany subsequently invaded Denmark and Norway, the Netherlands, and France, and began bombing Great Britain in preparation for Operation Sea Lion, the planned invasion of the United Kingdom.[102] On 21 June 1941, the day before invasion of the Soviet Union, Himmler commissioned the preparation of the Generalplan Ost (General Plan for the East); the plan was approved by Hitler in May 1942. It called for the Baltic States, Poland, Western Ukraine, and Byelorussia to be conquered and resettled by ten million German citizens. The current residents—some 31 million people—would be expelled further east, starved, or used for forced labour. The plan would have extended the borders of Germany to the east by one thousand kilometres (600 miles). Himmler expected that it would take twenty to thirty years to complete the plan, at a cost of 67 billion ℛ︁ℳ︁.[103] Himmler stated openly: "It is a question of existence, thus it will be a racial struggle of pitiless severity, in the course of which 20 to 30 million Slavs and Jews will perish through military actions and crises of food supply."[104]

Himmler declared that the war in the east was a pan-European crusade to defend the traditional values of old Europe from the "Godless Bolshevik hordes".[105] Constantly struggling with the Wehrmacht for recruits, Himmler solved this problem through the creation of Waffen-SS units composed of Germanic folk groups taken from the Balkans and eastern Europe. Equally vital were recruits from among the Germanic considered peoples of northern and western Europe, in the Netherlands, Norway, Belgium, Denmark and Finland.[106] Spain and Italy also provided men for Waffen-SS units.[107] Among western countries, the number of volunteers varied from a high of 25,000 from the Netherlands[108] to 300 each from Sweden and Switzerland. From the east, the highest number of men came from Lithuania (50,000) and the lowest from Bulgaria (600).[109] After 1943 most men from the east were conscripts. The performance of the eastern Waffen-SS units was, as a whole, sub-standard.[110]

In late 1941, Hitler named Heydrich as Deputy Reich Protector of the newly established Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. Heydrich began to racially classify the Czechs, deporting many to concentration camps. Members of a swelling resistance were shot, earning Heydrich the nickname "the Butcher of Prague".[111] This appointment strengthened the collaboration between Himmler and Heydrich, and Himmler was proud to have SS control over a state. Despite having direct access to Hitler, Heydrich's loyalty to Himmler remained firm.[112]

With Hitler's approval, Himmler re-established the Einsatzgruppen in the lead-up to the planned invasion of the Soviet Union. In March 1941, Hitler addressed his army leaders, detailing his intention to smash the Soviet Empire and destroy the Bolshevik intelligentsia and leadership.[113] His special directive, the "Guidelines in Special Spheres re Directive No. 21 (Operation Barbarossa)", read: "In the operations area of the army, the Reichsführer-SS has been given special tasks on the orders of the Führer, in order to prepare the political administration. These tasks arise from the forthcoming final struggle of two opposing political systems. Within the framework of these tasks, the Reichsführer-SS acts independently and on his own responsibility."[114] Hitler thus intended to prevent internal friction like that occurring earlier in Poland in 1939, when several German Army generals had attempted to bring Einsatzgruppen leaders to trial for the murders they had committed.[114]

Following the army into the Soviet Union, the Einsatzgruppen rounded up and killed Jews and others deemed undesirable by the Nazi state.[115] Hitler was sent frequent reports.[116] In addition, 2.8 million Soviet prisoners of war died of starvation, mistreatment or executions in just eight months of 1941–42.[117] As many as 500,000 Soviet prisoners of war died or were executed in Nazi concentration camps over the course of the war; most of them were shot or gassed.[118] By early 1941, following Himmler's orders, ten concentration camps had been constructed in which inmates were subjected to forced labour.[119] Jews from all over Germany and the occupied territories were deported to the camps or confined to ghettos. As the Germans were pushed back from Moscow in December 1941, signalling that the expected quick defeat of the Soviet Union had failed to materialize, Hitler and other Nazi officials realised that mass deportations to the east would no longer be possible. As a result, instead of deportation, many Jews in Europe were destined for death.[120][121]

Final Solution, the Holocaust, racial policy, and eugenics

| Part of a series on |

| The Holocaust |

|---|

|

Nazi racial policies, including the notion that people who were racially inferior had no right to live, date back to the earliest days of the party; Hitler discusses this in Mein Kampf.[122] Around the time of the German declaration of war on the United States in December 1941, Hitler resolved that the Jews of Europe were to be "exterminated".[121] Heydrich arranged a meeting, held on 20 January 1942 at Wannsee, a suburb of Berlin. Attended by top Nazi officials, it was used to outline the plans for the "final solution to the Jewish question". Heydrich detailed how those Jews able to work would be worked to death; those unable to work would be killed outright. Heydrich calculated the number of Jews to be killed at 11 million and told the attendees that Hitler had placed Himmler in charge of the plan.[123]

In June 1942, Heydrich was assassinated in Prague in Operation Anthropoid, led by Jozef Gabčík and Jan Kubiš, members of Czechoslovakia's army-in-exile. Both men had been trained by the British Special Operations Executive for the mission to kill Heydrich.[124] During the two funeral services, Himmler—the chief mourner—took charge of Heydrich's two young sons, and he gave the eulogy in Berlin.[125] On 9 June, after discussions with Himmler and Karl Hermann Frank, Hitler ordered brutal reprisals for Heydrich's death.[124] Over 13,000 people were arrested, and the village of Lidice was razed to the ground; its male inhabitants and all adults in the village of Ležáky were murdered. At least 1,300 people were executed by firing squads.[126][127] Himmler took over leadership of the RSHA and stepped up the pace of the killing of Jews in Aktion Reinhard (Operation Reinhard), named in Heydrich's honour.[128] He ordered the Aktion Reinhard camps—three extermination camps—to be constructed at Bełżec, Sobibór, and Treblinka.[129]

Initially the victims were killed with gas vans or by firing squad, but these methods proved impracticable for an operation of this scale.[130] In August 1941, Himmler attended the shooting of 100 Jews at Minsk. Nauseated and shaken by the experience,[131] he was concerned about the impact such actions would have on the mental health of his SS men. He decided that alternate methods of killing should be found.[132][133] On his orders, by early 1942 the camp at Auschwitz had been greatly expanded, including the addition of gas chambers, where victims were killed using the pesticide Zyklon B.[134] Himmler visited the camp in person on 17 and 18 July 1942. He was given a demonstration of a mass killing using the gas chamber in Bunker 2 and toured the building site of the new IG Farben plant being constructed at the nearby town of Monowitz.[135] By the end of the war, at least 5.5 million Jews had been killed by the Nazi regime;[136] most estimates range closer to 6 million.[137][138] Himmler visited the camp at Sobibór in early 1943, by which time 250,000 people had been killed at that location alone. After witnessing a gassing, he gave 28 people promotions and ordered the operation of the camp to be wound down. In a prisoner revolt that October, the remaining prisoners killed most of the guards and SS personnel. Several hundred prisoners escaped; about a hundred were immediately re-captured and killed. Some of the escapees joined partisan units operating in the area. The camp was dismantled by December 1943.[139]

The Nazis also targeted Romani (Gypsies) as "asocial" and "criminals".[140] By 1935, they were confined into special camps away from ethnic Germans.[140] In 1938, Himmler issued an order in which he said that the "Gypsy question" would be determined by "race".[141] Himmler believed that the Romani were originally Aryan but had become a mixed race; only the "racially pure" were to be allowed to live.[142] In 1939, Himmler ordered thousands of Gypsies to be sent to the Dachau concentration camp and by 1942, ordered all Romani sent to Auschwitz concentration camp.[143]

Himmler was one of the main architects of the Holocaust,[144][145][146] using his deep belief in the racist Nazi ideology to justify the murder of millions of victims. Longerich surmises that Hitler, Himmler, and Heydrich designed the Holocaust during a period of intensive meetings and exchanges in April–May 1942.[147] The Nazis planned to kill Polish intellectuals and restrict non-Germans in the General Government and conquered territories to a fourth-grade education.[148] They further wanted to breed a master race of racially pure Nordic Aryans in Germany. As a student of agriculture and a farmer, Himmler was acquainted with the principles of selective breeding, which he proposed to apply to humans. He believed that he could engineer the German populace, for example, through eugenics, to be Nordic in appearance within several decades of the end of the war.[149]

Posen speeches

On 4 October 1943, during a secret meeting with top SS officials in the city of Poznań (Posen), and on 6 October 1943, in a speech to the party elite—the Gauleiters and Reichsleiters—Himmler referred explicitly to the "extermination" (German: Ausrottung) of the Jewish people.[150]

A translated excerpt from the speech of 4 October reads:[151]

I also want to refer here very frankly to a very difficult matter. We can now very openly talk about this among ourselves, and yet we will never discuss this publicly. Just as we did not hesitate on 30 June 1934, to perform our duty as ordered and put comrades who had failed up against the wall and execute them, we also never spoke about it, nor will we ever speak about it. Let us thank God that we had within us enough self-evident fortitude never to discuss it among us, and we never talked about it. Every one of us was horrified, and yet every one clearly understood that we would do it next time, when the order is given and when it becomes necessary.

I am talking about the "Jewish evacuation": the extermination of the Jewish people. It is one of those things that is easily said. "The Jewish people is being exterminated", every Party member will tell you, "perfectly clear, it's part of our plans, we're eliminating the Jews, exterminating them, ha!, a small matter." And then they turn up, the upstanding 80 million Germans, and each one has his decent Jew. They say the others are all swines, but this particular one is a splendid Jew. But none has observed it, endured it. Most of you here know what it means when 100 corpses lie next to each other, when there are 500 or when there are 1,000. To have endured this and at the same time to have remained a decent person—with exceptions due to human weaknesses—has made us tough, and is a glorious chapter that has not and will not be spoken of. Because we know how difficult it would be for us if we still had Jews as secret saboteurs, agitators and rabble-rousers in every city, what with the bombings, with the burden and with the hardships of the war. If the Jews were still part of the German nation, we would most likely arrive now at the state we were at in 1916 and '17 ...[152][153]

Because the Allies had indicated that they were going to pursue criminal charges for German war crimes, Hitler tried to gain the loyalty and silence of his subordinates by making them all parties to the ongoing genocide. Hitler therefore authorised Himmler's speeches to ensure that all party leaders were complicit in the crimes and could not later deny knowledge of the killings.[150]

Germanization

As Reich Commissioner for the Consolidation of German Nationhood (RKFDV) with the incorporated VoMi, Himmler was deeply involved in the Germanization program for the East, particularly Poland. As laid out in Generalplan Ost, the aim was to enslave, expel or exterminate the native population and to make Lebensraum ("living space") for Volksdeutsche (ethnic Germans). He continued his plans to colonise the east, even when many Germans were reluctant to relocate there, and despite negative effects on the war effort.[154][155]

Himmler's racial groupings began with the Volksliste, the classification of people deemed of German blood. These included Germans who had collaborated with Germany before the war, but also those who considered themselves German but had been neutral; those who were partially "Polonized" but "Germanizable"; and Germans who were of Polish nationality.[156] Himmler ordered that those who refused to be classified as ethnic Germans should be deported to concentration camps, have their children taken away, or be assigned to forced labour.[157][158] Himmler's belief that "it is in the nature of German blood to resist" led to his conclusion that Balts or Slavs who resisted Germanization were racially superior to more compliant ones.[159] He declared that no drop of German blood would be lost or left behind to mingle with an "alien race".[155]

The plan also included the kidnapping of Eastern European children by Nazi Germany.[160] Himmler urged:

Obviously in such a mixture of peoples, there will always be some racially good types. Therefore, I think that it is our duty to take their children with us, to remove them from their environment, if necessary by robbing, or stealing them. Either we win over any good blood that we can use for ourselves and give it a place in our people, ... or we destroy that blood.[161]

The "racially valuable" children were to be removed from all contact with Poles and raised as Germans, with German names.[160] Himmler declared: "We have faith above all in this our own blood, which has flowed into a foreign nationality through the vicissitudes of German history. We are convinced that our own philosophy and ideals will reverberate in the spirit of these children who racially belong to us."[160] The children were to be adopted by German families.[158] Children who passed muster at first but were later rejected were taken to Kinder KZ in Łódź Ghetto, where most of them eventually died.[160]

By January 1943, Himmler reported that 629,000 ethnic Germans had been resettled; however, most resettled Germans did not live in the envisioned small farms, but in temporary camps or quarters in towns. Half a million residents of the annexed Polish territories, as well as from Slovenia, Alsace, Lorraine, and Luxembourg were deported to the General Government or sent to Germany as slave labour.[162] Himmler instructed that the German nation should view all foreign workers brought to Germany as a danger to their German blood.[163] In accordance with German racial laws, sexual relations between Germans and foreigners were forbidden as Rassenschande (race defilement).[164]

20 July plot

On 20 July 1944, a group of German army officers led by Claus von Stauffenberg and including some of the highest-ranked members of the German armed forces attempted to assassinate Hitler, but failed to do so. The next day, Himmler formed a special commission that arrested over 5,000 suspected and known opponents of the regime. Hitler ordered brutal reprisals that resulted in the execution of more than 4,900 people.[165] Though Himmler was embarrassed by his failure to uncover the plot, it led to an increase in his powers and authority.[166][167]

General Friedrich Fromm, commander-in-chief of the Replacement Army (Ersatzheer) and Stauffenberg's immediate superior, was one of those implicated in the conspiracy. Hitler removed Fromm from his post and named Himmler as his successor. Since the Replacement Army consisted of two million men, Himmler hoped to draw on these reserves to fill posts within the Waffen-SS. He appointed Hans Jüttner, director of the SS Leadership Main Office, as his deputy, and began to fill top Replacement Army posts with SS men. By November 1944 Himmler had merged the army officer recruitment department with that of the Waffen-SS and had successfully lobbied for an increase in the quotas for recruits to the SS.[168]

By this time, Hitler had appointed Himmler as Reichsminister of the Interior, succeeding Frick, and General Plenipotentiary for Administration (Generalbevollmächtigter für die Verwaltung).[169] At the same time (24 August 1943) he also joined the six-member Council of Ministers for the Defense of the Reich, which operated as the war cabinet.[170] In August 1944 Hitler authorised him to restructure the organisation and administration of the Waffen-SS, the army, and the police services. As head of the Replacement Army, Himmler was now responsible for prisoners of war. He was also in charge of the Wehrmacht penal system, and controlled the development of Wehrmacht armaments until January 1945.[171]

Command of army group

On 6 June 1944, the Western Allied armies landed in northern France during Operation Overlord.[172] In response, Army Group Upper Rhine (Heeresgruppe Oberrhein) group was formed to engage the advancing US 7th Army (under command of General Alexander Patch[173]) and French 1st Army (led by General Jean de Lattre de Tassigny) in the Alsace region along the west bank of the Rhine.[174] In late 1944, Hitler appointed Himmler commander-in-chief of Army Group Upper Rhine.

On 26 September 1944 Hitler ordered Himmler to create special army units, the Volkssturm ("People's Storm" or "People's Army"). All males aged sixteen to sixty were eligible for conscription into this militia, over the protests of Armaments Minister Albert Speer, who noted that irreplaceable skilled workers were being removed from armaments production.[175] Hitler confidently believed six million men could be raised, and the new units would "initiate a people's war against the invader".[176] These hopes were wildly optimistic.[176] In October 1944, children as young as fourteen were being enlisted. Because of severe shortages in weapons and equipment and lack of training, members of the Volkssturm were poorly prepared for combat, and about 175,000 of them died in the final months of the war.[177]

On 1 January 1945, Hitler and his generals launched Operation North Wind. The goal was to break through the lines of the US 7th Army and French 1st Army to support the southern thrust in the Battle of the Bulge (Ardennes offensive), the final major German offensive of the war. After limited initial gains by the Germans, the Americans halted the offensive.[178] By 25 January, Operation North Wind had officially ended.

On 25 January 1945, despite Himmler's lack of military experience, Hitler appointed him as commander of the hastily formed Army Group Vistula (Heeresgruppe Weichsel) to halt the Soviet Red Army's Vistula–Oder offensive into Pomerania[179] – a decision that appalled the German General Staff.[180] Himmler established his command centre at Schneidemühl, using his special train, Sonderzug Steiermark, as his headquarters. The train had only one telephone line, inadequate maps, and no signal detachment or radios with which to establish communication and relay military orders. Himmler seldom left the train, only worked about four hours per day, and insisted on a daily massage before commencing work and a lengthy nap after lunch.[181]

General Heinz Guderian talked to Himmler on 9 February and demanded, that Operation Solstice, an attack from Pomerania against the northern flank of Marshal Georgy Zhukov's 1st Belorussian Front, should be in progress by the 16th. Himmler argued that he was not ready to commit himself to a specific date. Given Himmler's lack of qualifications as an army group commander, Guderian convinced himself that Himmler tried to conceal his incompetence.[182] On 13 February Guderian met Hitler and demanded that General Walther Wenck be given a special mandate to command the offensive by Army Group Vistula. Hitler sent Wenck with a "special mandate", but without specifying Wenck's authority.[183] The offensive was launched on 16 February 1945, but soon stuck in rain and mud, facing mine fields and strong antitank defenses. That night Wenck was severely injured in a car accident, but it is doubtful that he could have salvaged the operation, as Guderian later claimed. Himmler ordered the offensive to stop on the 18th by a "directive for regrouping".[184] Hitler officially ended Operation Solstice on 21 February and ordered Himmler to transfer a corps headquarter and three divisions to Army Group Center.[185]

Himmler was unable to devise any viable plans for completion of his military objectives. Under pressure from Hitler over the worsening military situation, Himmler became anxious and unable to give him coherent reports.[186] When the counter-attack failed to stop the Soviet advance, Hitler held Himmler personally liable and accused him of not following orders. Himmler's military command ended on 20 March, when Hitler replaced him with General Gotthard Heinrici as Commander-in-Chief of Army Group Vistula. By this time Himmler, who had been under the care of his doctor since 18 February, had fled to the Hohenlychen Sanatorium.[187] Hitler sent Guderian on a forced medical leave of absence, and he reassigned his post as chief of staff to Hans Krebs on 29 March.[188] Himmler's failure and Hitler's response marked a serious deterioration in the relationship between the two men.[189] By that time, the inner circle of people whom Hitler trusted was rapidly shrinking.[190]

Peace negotiations

In early 1945, the German war effort was on the verge of collapse and Himmler's relationship with Hitler had deteriorated. Himmler considered independently negotiating a peace settlement. His masseur, Felix Kersten, who had moved to Sweden, acted as an intermediary in negotiations with Count Folke Bernadotte, head of the Swedish Red Cross. Letters were exchanged between the two men,[191] and direct meetings were arranged by Walter Schellenberg of the RSHA.[192]

In March 1945, Himmler issued a directive that Jews were to be marched from the South-east wall (Südostwall) fortifications construction project on the Austro-Hungarian border, to Mauthausen. He desired hostages for potential peace negotiations. Thousands died on the marches.[193][194]

Himmler and Hitler met for the last time on 20 April 1945—Hitler's birthday—in Berlin, and Himmler swore unswerving loyalty to Hitler. At a military briefing on that day, Hitler stated that he would not leave Berlin, in spite of Soviet advances. Along with Göring, Himmler quickly left the city after the briefing.[195] On 21 April, Himmler met with Norbert Masur, a Swedish representative of the World Jewish Congress, to discuss the release of Jewish concentration camp inmates.[196] As a result of these negotiations, about 20,000 people were released in the White Buses operation.[197] Himmler falsely claimed in the meeting that the crematoria at camps had been built to deal with the bodies of prisoners who had died in a typhus epidemic. He also claimed very high survival rates for the camps at Auschwitz and Bergen-Belsen, even as these sites were liberated and it became obvious that his figures were false.[198]

On 23 April, Himmler met directly with Bernadotte at the Swedish consulate in Lübeck. Representing himself as the provisional leader of Germany, he claimed that Hitler would be dead within the next few days. Hoping that the British and Americans would fight the Soviets alongside what remained of the Wehrmacht, Himmler asked Bernadotte to inform General Dwight Eisenhower that Germany wished to surrender to the Western Allies, and not to the Soviet Union. Bernadotte asked Himmler to put his proposal in writing, and Himmler obliged.[199][200]

Meanwhile, Göring had sent a telegram, a few hours earlier, asking Hitler for permission to assume leadership of the Reich in his capacity as Hitler's designated deputy—an act that Hitler, under the prodding of Martin Bormann, interpreted as a demand to step down or face a coup. On 27 April, Himmler's SS representative at Hitler's HQ in Berlin, Hermann Fegelein, was caught in civilian clothes preparing to desert; he was arrested and brought back to the Führerbunker. On the evening of 28 April, the BBC broadcast a Reuters news report about Himmler's attempted negotiations with the western Allies. Hitler had long considered Himmler to be second only to Joseph Goebbels in loyalty; he called Himmler "the loyal Heinrich" (German: der treue Heinrich). Hitler flew into a rage at this betrayal, and told those still with him in the bunker complex that Himmler's secret negotiations were the worst treachery he had ever known. Hitler ordered Himmler's arrest, and Fegelein was court-martialed and shot.[201]

By this time, the Soviets had advanced to the Potsdamer Platz, only 300 m (330 yd) from the Reich Chancellery, and were preparing to storm the Chancellery. This report, combined with Himmler's treachery, prompted Hitler to write his last will and testament. In the testament, completed on 29 April—one day prior to his suicide—Hitler declared both Himmler and Göring to be traitors. He stripped Himmler of all of his party and state offices and expelled him from the Nazi Party.[202][203]

Hitler named Grand Admiral Karl Dönitz as his successor. Himmler met Dönitz in Flensburg and offered himself as second-in-command. He maintained that he was entitled to a position in Dönitz's interim government as Reichsführer-SS, believing the SS would be in a good position to restore and maintain order after the war. Dönitz repeatedly rejected Himmler's overtures[204] and initiated peace negotiations with the Allies. He wrote a letter on 6 May—two days before the German Instrument of Surrender—formally dismissing Himmler from all his posts.[205]

Capture and death

Rejected by his former comrades and hunted by the Allies, Himmler attempted to go into hiding. He had not made extensive preparations for this, but he carried a forged paybook under the name of Sergeant Heinrich Hizinger. With a small band of companions, he headed south on 11 May to Friedrichskoog, without a final destination in mind. They continued on to Neuhaus, where the group split up. On 21 May, Himmler and two aides were stopped and detained at a checkpoint in Bremervörde set up by former Soviet POWs. Over the following two days, he was moved around to several camps[206] and was brought to the British 31st Civilian Interrogation Camp near Lüneburg, on 23 May.[207] The officials noticed that Himmler's identity papers bore a stamp which British military intelligence had seen being used by fleeing members of the SS.[208]

The duty officer, Captain Thomas Selvester, began a routine interrogation. Himmler admitted who he was, and Selvester had the prisoner searched. Himmler was taken to the headquarters of the Second British Army in Lüneburg, where a doctor conducted a medical exam on him. The doctor attempted to examine the inside of Himmler's mouth, but the prisoner was reluctant to open it and jerked his head away. Himmler then bit into a hidden potassium cyanide pill and collapsed onto the floor. He was dead within 15 minutes,[209][210] despite efforts to expel the poison from his system.[211] Shortly afterward, Himmler's body was buried in an unmarked grave near Lüneburg. The grave's location remains unknown.[212]

Mysticism and symbolism

Himmler was interested in mysticism and the occult from an early age. He tied this interest into his racist philosophy, looking for proof of Aryan and Nordic racial superiority from ancient times. He promoted a cult of ancestor worship, particularly among members of the SS, as a way to keep the race pure and provide immortality to the nation. Viewing the SS as an "order" along the lines of the Teutonic Knights, he had them take over the Church of the Teutonic Order in Vienna in 1939. He began the process of replacing Christianity with a new moral code that rejected humanitarianism and challenged the Christian concept of marriage.[213] The Ahnenerbe, a research society founded by Himmler in 1935, searched the globe for proof of the superiority and ancient origins of the Germanic race.[214][215]

All regalia and uniforms of Nazi Germany, particularly those of the SS, used symbolism in their designs. The stylised lightning bolt logo of the SS was chosen in 1932. The logo is a pair of runes from a set of 18 Armanen runes created by Guido von List in 1906. The ancient Sowilō rune originally symbolised the sun, but was renamed "Sieg" (victory) in List's iconography.[216] Himmler modified a variety of existing customs to emphasise the elitism and central role of the SS; an SS naming ceremony was to replace baptism, marriage ceremonies were to be altered, a separate SS funeral ceremony was to be held in addition to Christian ceremonies, and SS-centric celebrations of the summer and winter solstices were instituted.[217][218] The Totenkopf (death's head) symbol, used by German military units for hundreds of years, had been chosen for the SS by Julius Schreck.[219] Himmler placed particular importance on the death's-head rings; they were never to be sold, and were to be returned to him upon the death of the owner. He interpreted the death's-head symbol to mean solidarity to the cause and a commitment unto death.[220]

Relationship with Hitler

As second in command of the SS and then Reichsführer-SS, Himmler was in regular contact with Hitler to arrange for SS men as bodyguards;[221] Himmler was not involved with Nazi Party policy-making decisions in the years leading up to the seizure of power.[222] From the late 1930s, the SS was independent of the control of other state agencies or government departments, and he reported only to Hitler.[223]

Hitler promoted and practised the Führerprinzip. The principle required absolute obedience of all subordinates to their superiors; thus Hitler viewed the government structure as a pyramid, with himself—the infallible leader—at the apex.[224] Accordingly, Himmler placed himself in a position of subservience to Hitler, and was unconditionally obedient to him.[225] However, he—like other top Nazi officials—had aspirations to one day succeed Hitler as leader of the Reich.[226] Himmler considered Speer to be an especially dangerous rival, both in the Reich administration and as a potential successor to Hitler.[227]

Hitler called Himmler's mystical and pseudoreligious interests "nonsense".[228] Himmler was not a member of Hitler's inner circle; the two men were not very close, and rarely saw each other socially.[229][230] Himmler socialised almost exclusively with other members of the SS.[231] His unconditional loyalty and efforts to please Hitler earned him the nickname of der treue Heinrich ("the faithful Heinrich"). In the last days of the war, when it became clear that Hitler planned to die in Berlin, Himmler left his long-time superior to try to save himself.[232]

Marriage and family

Himmler met his future wife, Margarete Boden, in 1927. Seven years his senior, she was a nurse who shared his interest in herbal medicine and homoeopathy, and was part owner of a small private clinic. They were married in July 1928, and their only child, Gudrun, was born on 8 August 1929.[233] The couple were also foster parents to a boy named Gerhard von Ahe, son of an SS officer who had died before the war.[234] Margarete sold her share of the clinic and used the proceeds to buy a plot of land in Waldtrudering, near Munich, where they erected a prefabricated house. Himmler was constantly away on party business, so his wife took charge of their efforts—mostly unsuccessful—to raise livestock for sale. They had a dog, Töhle.[235]

After the Nazis came to power the family moved first to Möhlstrasse in Munich, and in 1934 to Tegernsee, where they bought a house. Himmler also later obtained a large house in the Berlin suburb of Dahlem, free of charge, as an official residence. The couple saw little of each other as Himmler became totally absorbed by work.[236] The relationship was strained.[237][238] The couple did unite for social functions; they were frequent guests at the Heydrich home. Margarete saw it as her duty to invite the wives of the senior SS leaders over for afternoon coffee and tea on Wednesday afternoons.[239]

Hedwig Potthast, Himmler's young secretary starting in 1936, became his mistress by 1939. She left her job in 1941. He arranged accommodation for her, first in Mecklenburg and later at Berchtesgaden. He fathered two children with her: a son, Helge (born 15 February 1942, Mecklenburg) and a daughter, Nanette Dorothea (born 20 July 1944, Berchtesgaden). Margarete, by then living in Gmund with her daughter, learned of the relationship sometime in 1941; she and Himmler were already separated, and she decided to tolerate the relationship for the sake of her daughter. Working as a nurse for the German Red Cross during the war, Margarete was appointed supervisor in one of Germany's military districts, Wehrkreis III (Berlin-Brandenburg). Himmler was close to his first daughter, Gudrun, whom he nicknamed Püppi ("dolly"); he phoned her every few days and visited as often as he could.[240]

Margarete's diaries reveal that Gerhard had to leave the National Political Educational Institute in Berlin because of poor results. At the age of 16 he joined the SS in Brno and shortly afterwards went "into battle". He was captured by the Russians but later returned to Germany.[241]

Hedwig and Margarete both remained loyal to Himmler. Writing to Gebhard in February 1945, Margarete said, "How wonderful that he has been called to great tasks and is equal to them. The whole of Germany is looking to him."[242] Hedwig expressed similar sentiments in a letter to Himmler in January. Margarete and Gudrun left Gmund as Allied troops advanced into the area. They were arrested by American troops in Bolzano, Italy, and held in various internment camps in Italy, France, and Germany. They were brought to Nuremberg to testify at the trials and were released in November 1946. Gudrun emerged from the experience embittered by her alleged mistreatment and remained devoted to her father's memory.[243][244] She later worked for the West German spy agency Bundesnachrichtendienst (BND) from 1961 to 1963.[245]

Historical assessment

Peter Longerich observes that Himmler's ability to consolidate his ever-increasing powers and responsibilities into a coherent system under the auspices of the SS led him to become one of the most powerful men in the Third Reich.[246] Historian Wolfgang Sauer says that "although he was pedantic, dogmatic, and dull, Himmler emerged under Hitler as second in actual power. His strength lay in a combination of unusual shrewdness, burning ambition, and servile loyalty to Hitler."[247] In 2008, the German news magazine Der Spiegel described Himmler as one of the most brutal mass murderers in history and the architect of the Holocaust.[248]

Historian John Toland relates a story by Günter Syrup, a subordinate of Heydrich. Heydrich showed him a picture of Himmler and said: "The top half is the teacher, but the lower half is the sadist."[249] Historian Adrian Weale comments that Himmler and the SS followed Hitler's policies without question or ethical considerations. Himmler accepted Hitler and Nazi ideology and saw the SS as a chivalric Teutonic order of new Germans. Himmler adopted the doctrine of Auftragstaktik ("mission command"), whereby orders were given as broad directives, with authority delegated downward to the appropriate level to carry them out in a timely and efficient manner. Weale states that the SS ideology gave the men a doctrinal framework, and the mission command tactics allowed the junior officers leeway to act on their own initiative to obtain the desired results.[250]

See also

References

Notes

- At that time Reichsführer-SS was only a titled position, not an actual SS rank (McNab 2009, pp. 18, 29).

Citations

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2007, p. 13.

- Himmler 2007.

- Longerich 2012, pp. 12–15.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2007, p. 1.

- Breitman 2004, p. 9.

- Longerich 2012, pp. 17–19.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2007, pp. 3, 6–7.

- Longerich 2012, p. 16.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2007, p. 8.

- Longerich 2012, pp. 20–26.

- Padfield 1990, pp. 36–37, 49–50, 57, 67.

- Breitman 2004, p. 12.

- Longerich 2012, p. 29.

- Evans 2003, pp. 22–25.

- Longerich 2012, pp. 33, 42.

- Longerich 2012, pp. 31, 35, 47.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2007, pp. 6, 8–9, 11.

- Longerich 2012, p. 54.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2007, p. 10.

- Weale 2010, p. 40.

- Weale 2010, p. 42.

- Longerich 2012, pp. 60, 64–65.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2007, pp. 9–11.

- Gellately 2020, p. 54.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2007, p. 11.

- Biondi 2000, p. 7.

- Longerich 2012, pp. 72–75.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2007, pp. 11–12.

- Longerich 2012, pp. 77–81, 87.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2007, pp. 11–13.

- Evans 2003, p. 227.

- Gerwarth 2011, p. 51.

- Longerich 2012, pp. 70, 81–88.

- Evans 2003, p. 228.

- Longerich 2012, pp. 89–92.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2007, pp. 15–16.

- McNab 2009, p. 18.

- Evans 2005, p. 84.

- Shirer 1960, p. 148.

- Weale 2010, p. 47.

- Longerich 2012, pp. 113–114.

- Evans 2003, pp. 228–229.

- McNab 2009, pp. 17, 19–21.

- Evans 2005, p. 9.

- Bullock 1999, p. 376.

- Williams 2015, p. 565.

- Kolb 2005, pp. 224–225.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2011, p. 92.

- Shirer 1960, p. 184.

- Shirer 1960, p. 192.

- Shirer 1960, p. 199.

- Shirer 1960, pp. 226–227.

- McNab 2009, pp. 20, 22.

- Pringle 2006, p. 41.

- Pringle 2006, p. 52.

- McNab 2009, pp. 17, 23, 151.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2007, pp. 24, 27.

- Longerich 2012, p. 149.

- Flaherty 2004, p. 66.

- McNab 2009, p. 29.

- Frank 1933–1934, p. 254.

- McNab 2009, pp. 23, 36.

- Longerich 2012, pp. 127, 353.

- Longerich 2012, p. 302.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2007, pp. 22–23.

- Longerich 2012, p. 378.

- Evans 2003, p. 344.

- McNab 2009, pp. 136, 137.

- Longerich 2012, pp. 151–153.

- Evans 2005, pp. 84–85.

- Himmler 1936.

- Evans 2005, p. 87.

- Evans 2005, pp. 86–90.

- Kershaw 2008, pp. 306–309.

- Evans 2005, p. 24.

- Evans 2005, p. 54.

- Williams 2001, p. 61.

- Kershaw 2008, pp. 308–314.

- Evans 2005, pp. 31–35, 39.

- Kershaw 2008, p. 316.

- Kershaw 2008, p. 313.

- Evans 2005, pp. 543–545.

- Gerwarth 2011, pp. 86, 87.

- Williams 2001, p. 77.

- Longerich 2012, p. 204.

- Longerich 2012, p. 201.

- Gerwarth 2011, p. 163.

- McNab 2009, pp. 56, 57, 66.

- Sereny 1996, pp. 323, 329.

- Evans 2008, p. 343.

- Flaherty 2004, p. 120.

- Evans 2005, pp. 641, 653, 674.

- Evans 2003, p. 34.

- Evans 2005, pp. 554–558.

- Longerich 2012, p. 265.

- Longerich 2012, p. 270.

- Padfield 1990, p. 170.

- Shirer 1960, pp. 518–520.

- McNab 2009, pp. 118, 122.

- Kershaw 2008, pp. 518, 519.

- Evans 2008, pp. 14–15.

- Evans 2008, pp. 118–145.

- Evans 2008, pp. 173–174.

- Cesarani 2004, p. 366.

- McNab 2009, pp. 93, 98.

- Koehl 2004, pp. 212–213.

- McNab 2009, pp. 81–84.

- van Roekel 2010.

- McNab 2009, pp. 84, 90.

- McNab 2009, p. 94.

- Evans 2008, p. 274.

- Gerwarth 2011, p. 225.

- Kershaw 2008, pp. 598, 618.

- Hillgruber 1989, p. 95.

- Shirer 1960, p. 958.

- Longerich, Chapter 15 2003.

- Goldhagen 1996, p. 290.

- POWs: Holocaust Memorial Museum.

- Longerich 2012, pp. 480–481.

- Evans 2008, p. 256.

- Longerich, Chapter 17 2003.

- Shirer 1960, p. 86.

- Evans 2008, p. 264.

- Gerwarth 2011, p. 280.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2007, p. 129.

- Gerwarth 2011, pp. 280–285.

- Kershaw 2008, p. 714.

- Longerich 2012, pp. 570–571.

- Evans 2008, pp. 282–283.

- Evans 2008, pp. 256–257.

- Gilbert 1987, p. 191.

- Longerich 2012, p. 547.

- Gerwarth 2011, p. 199.

- Evans 2008, pp. 295, 299–300.

- Steinbacher 2005, p. 106.

- Evans 2008, p. 318.

- Yad Vashem, 2008.

- Introduction: Holocaust Memorial Museum.

- Evans 2008, pp. 288–289.

- Longerich 2012, p. 229.

- Longerich 2012, p. 230.

- Lewy 2000, pp. 135–137.

- Longerich 2012, pp. 230, 670.

- Zentner & Bedürftig 1991, p. 1150.

- Shirer 1960, p. 236.

- Longerich 2012, p. 3.

- Longerich 2012, p. 564.

- Longerich 2012, pp. 429, 451.

- Pringle 2006.

- Sereny 1996, pp. 388–389.

- Posen speech (1943), audio recording.

- Posen speech (1943), transcript.

- IMT : Volume 29, p. 145f.

- Cecil 1972, p. 191.

- Overy 2004, p. 543.

- Overy 2004, p. 544.

- Nicholas 2006, p. 247.

- Lukas 2001, p. 113.

- Cecil 1972, p. 199.

- Sereny 1999.

- Kohn-Bramstedt 1998, p. 244.

- Longerich 2012, pp. 578–580.

- Rupp 1979, p. 125.

- Majer 2003, pp. 180, 855.

- Shirer 1960, §29.

- Longerich 2012, pp. 696–698.

- Evans 2008, p. 642.

- Longerich 2012, pp. 698–702.

- Lisciotto 2007.

- The Career of Heinrich Himmler 2001, pp. 50, 67.

- Longerich 2012, pp. 702–704.

- Shirer 1960, p. 1036.

- Shirer 1960, p. 1086.

- Longerich 2012, p. 715.

- Shirer 1960, p. 1087.

- The Battle for Germany 2011.

- Evans 2008, pp. 675–678.

- Kershaw 2008, pp. 884, 885.

- Kershaw 2008, p. 891.

- Shirer 1960, p. 1095.

- Duffy 1991, p. 178.

- Ziemke 1968, p. 446.

- Ziemke 1968, p. 446-447.

- Ziemke 1968, p. 447.

- Ziemke 1968, p. 448.

- Longerich 2012, pp. 715–718.

- Duffy 1991, p. 241.

- Duffy 1991, p. 247.

- Kershaw 2008, pp. 891, 913–914.

- Kershaw 2008, p. 914.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2007, pp. 230–233.

- Kershaw 2008, pp. 943–945.

- Rathkolb 2022, p. 138.

- Nuremberg Trials 1946.

- Kershaw 2008, pp. 923–925, 943.

- Penkower 1988, p. 281.

- Longerich 2012, p. 724.

- Longerich 2012, pp. 727–729.

- Shirer 1960, p. 1122.

- Trevor-Roper 2012, pp. 118–119.

- Kershaw 2008, pp. 943–947.

- Evans 2008, p. 724.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2007, p. 237.

- Longerich 2012, pp. 733–734.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2007, pp. 239, 243.

- Longerich 2012, pp. 734–736.

- Longerich 2012, pp. 1, 736.

- Corera 2020.

- Bend Bulletin 1945.

- Longerich 2012, pp. 1–3.

- Shirer 1960, p. 1141.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2007, p. 248.

- Longerich 2012, pp. 256–273.

- Yenne 2010, p. 134.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2007, p. 50.

- Yenne 2010, p. 64.

- Yenne 2010, pp. 93, 94.

- Flaherty 2004, pp. 38–45, 48, 49.

- Yenne 2010, p. 71.

- Longerich 2012, p. 287.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2007, p. 16.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2007, p. 20.

- Longerich 2012, p. 251.

- Kershaw 2008, p. 181.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2007, p. 83.

- Sereny 1996, pp. 322–323.

- Sereny 1996, pp. 424–425.

- Speer 1971, p. 141, 212.

- Toland 1977, p. 869.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2007, p. 29.

- Speer 1971, p. 80.

- Weale 2010, pp. 4, 407–408.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2007, p. 17.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2007, p. 258.

- Longerich 2012, p. 109–110.

- Flaherty 2004, p. 27.

- Longerich 2012, pp. 109, 374–375.

- Manvell & Fraenkel 2007, p. 40–41.

- Gerwarth 2011, p. 111.

- Longerich 2012, pp. 466–68.

- Himmler 2007, p. 285.

- Longerich 2012, p. 732.

- Himmler 2007, p. 275.

- Sify News 2010.

- Deutsche Welle 2018.

- Longerich 2012, p. 747.

- Sauer, Wolfgang.

- Von Wiegrefe 2008.

- Toland 1977, p. 812.

- Weale 2010, pp. 3, 4.

Bibliography

Printed

- Biondi, Robert, ed. (2000) [1942]. SS Officers List: (as of 30 January 1942): SS-Standartenfuhrer to SS-Oberstgruppenfuhrer: Assignments and Decorations of the Senior SS Officer Corps. Atglen, PA: Schiffer. ISBN 978-0-7643-1061-4.

- Breitman, Richard (2004). Himmler and the Final Solution: The Architect of Genocide. London: Pimlico. ISBN 978-1-84413-089-4.

- Bullock, Alan (1999) [1952]. Hitler: A Study in Tyranny. New York: Konecky & Konecky. ISBN 978-1-56852-036-0.

- Cecil, Robert (1972). The Myth of the Master Race: Alfred Rosenberg and Nazi Ideology. New York: Dodd, Mead. ISBN 978-0-396-06577-7.

- Cesarani, David (2004). Holocaust: From the Persecution of the Jews to Mass Murder. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-27511-8.

- Duffy, Christopher (1991). Red Storm on the Reich: The Soviet March On Germany, 1945. New York: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-80505-9.

- Evans, Richard J. (2003). The Coming of the Third Reich. New York: Penguin Group. ISBN 978-0-14-303469-8.

- Evans, Richard J. (2005). The Third Reich in Power. New York: Penguin Group. ISBN 978-0-14-303790-3.

- Evans, Richard J. (2008). The Third Reich at War. New York: Penguin Group. ISBN 978-0-14-311671-4.

- Flaherty, T. H. (2004) [1988]. The Third Reich: The SS. Time-Life Books, Inc. ISBN 1-84447-073-3.

- Frank, Hans, ed. (1933–1934). Jahrbuch der Akademie für Deutsches Recht [Yearbook of the Academy for German Law] (1st ed.). München/Berlin/Leipzig: Schweitzer Verlag.

- Gellately, Robert (2020). Hitler's True Believers: How Ordinary People Became Nazis. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-068990-2.

- Gerwarth, Robert (2011). Hitler's Hangman: The Life of Heydrich. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-11575-8.

- Gilbert, Martin (1987) [1985]. The Holocaust: A History of the Jews of Europe During the Second World War. New York: Holt. ISBN 978-0-8050-0348-2.

- Goldhagen, Daniel (1996). Hitler's Willing Executioners: Ordinary Germans and the Holocaust. New York: Knopf. ISBN 978-0-679-44695-8.

- Grazhdan, Anna (director); Artem Drabkin & Aleksey Isaev (writers); Valeriy Babich, Vlad Ryashin, et al. (producers) (2011). The Battle for Germany (television documentary). Soviet Storm: World War II in the East. Star Media's Official YouTube Channel. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- Hillgruber, Andreas (1989). The Nazi Holocaust Part 3, The "Final Solution": The Implementation of Mass Murder, Volume 1. Westpoint, CT: Meckler. ISBN 978-0-88736-266-8.

- Himmler, Katrin (2007). The Himmler Brothers. London: Pan Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-330-44814-7.

- Internationaler Militärgerichtshof Nürnberg (IMT) (1989). Der Nürnberger Prozess gegen die Hauptkriegsverbrecher (in German). Vol. Band 29: Urkunden und anderes Beweismaterial. Nachdruck München: Delphin Verlag. ISBN 978-3-7735-2523-9.

- Kershaw, Ian (2008). Hitler: A Biography. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-06757-6.

- Koehl, Robert (2004). The SS: A History 1919–45. Stroud: Tempus. ISBN 978-0-75242-559-7.

- Kohn-Bramstedt, Ernest (1998) [1945]. Dictatorship and Political Police: The Technique of Control by Fear. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-17542-5.

- Kolb, Eberhard (2005) [1984]. The Weimar Republic. London; New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-34441-8.

- Lewy, Guenter (2000). The Nazi Persecution of the Gypsies. Oxford University Press USA. ISBN 0195142403.

- Longerich, Peter (2012). Heinrich Himmler: A Life. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-959232-6.

- Lukas, Richard C. (2001) [1994]. Did the Children Cry?: Hitler's War Against Jewish and Polish Children, 1939–1945. New York: Hippocrene. ISBN 978-0-7818-0870-5.

- Majer, Diemut (2003). "Non-Germans" Under the Third Reich: The Nazi Judicial and Administrative System in Germany and Occupied Eastern Europe with Special Regard to Occupied Poland, 1939–1945. Baltimore; London: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-6493-3.

- Manvell, Roger; Fraenkel, Heinrich (2011) [1962]. Goering: The Rise and Fall of the Notorious Nazi Leader. London: Skyhorse. ISBN 978-1-61608-109-6.

- Manvell, Roger; Fraenkel, Heinrich (2007) [1965]. Heinrich Himmler: The Sinister Life of the Head of the SS and Gestapo. London; New York: Greenhill; Skyhorse. ISBN 978-1-60239-178-9.

- McNab, Chris (2009). The SS: 1923–1945. London: Amber Books. ISBN 978-1-906626-49-5.

- Nicholas, Lynn H. (2006) [2005]. Cruel World: The Children of Europe in the Nazi Web. New York: Vintage. ISBN 978-0-679-77663-5.

- Overy, Richard (2004). The Dictators: Hitler's Germany, Stalin's Russia. New York: Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-02030-4.

- Trial of The Major War Criminals before The Internal Military Tribunal, Nuremberg, 14 November 1945 – 1 October 1946. One hundred and thirty-eighth day, Friday, 24 May 1946 (PDF). International Military Tribunal Nuremberg. 1948. p. 440. Retrieved 26 June 2023.

- Padfield, Peter (1990). Himmler: Reichsführer-SS. New York: Henry Holt. ISBN 0-8050-2699-1.

- Penkower, Monty Noam (1988). The Jews Were Expendable: Free World Diplomacy and the Holocaust. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8143-1952-9.

- Pringle, Heather (2006). The Master Plan: Himmler's Scholars and the Holocaust. New York: Hyperion. ISBN 978-0-7868-6886-5.

- Rathkolb, Oliver (2022). Baldur von Schirach: Nazi Leader and Head of the Hitler Youth. Frontline Books. ISBN 978-1-3990-2096-1.

- Rupp, Leila J. (1979). Mobilizing Women for War: German and American Propaganda, 1939–1945. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-04649-2.

- Sereny, Gitta (1996) [1995]. Albert Speer: His Battle With Truth. New York; Toronto: Random House. ISBN 978-0-679-76812-8.

- Shirer, William L. (1960). The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-62420-0.