Louisa Gould

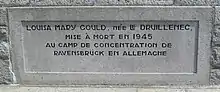

Louisa Mary Gould (7 October 1891 – 13 February 1945)[1] was a Jersey shopkeeper and a member of the British resistance movement in the Channel Islands during World War II. From 1942 until her arrest in 1944, Gould sheltered an escaped Soviet slave worker known as Feodor Polycarpovitch Burriy on the island of Jersey. Following a trial, she was sent to the Ravensbrück concentration camp where she was gassed to death in 1945. In 2010 she was posthumously named a British Hero of the Holocaust.

Life

Gould was born Louisa Eva Le Druillenec in St Ouen, Jersey, on 7 October 1891.[2][3][4] For most of her life she ran a grocery store at La Fontaine, Millais in St Ouen.[5][6][7]

Gould had two sons, Ralph and Edward, both of whom enlisted in the British armed forces during World War II.[8][9] Edward, an officer in the Royal Navy Volunteer Reserve, was killed in action in 1941.[6]

Resistance

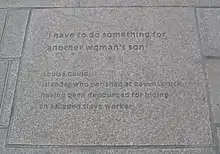

During the World War II occupation of the Channel Islands, the Nazis used captured Russian soldiers as slave workers.[10] Beginning in late 1942, Gould hid Fyodr Polycarpovitch Burriy, an escaped Soviet slave and former pilot who had been captured after his aircraft had been shot down.[11] Aware of the severe penalties for harbouring enemies of the Germans, Gould said simply "I have to do something for another mother's son."[9] Gould hid Burriy inside her St. Ouen home for 18 months.[12]

Arrest, trial and death

A neighbour later reported that Gould was harbouring Burriy, whom she called "Bill."[11][13] In June 1944, the German forces searched her house. While they did not find Burriy, they found a scrap of paper that had been used as a Christmas gift tag, addressed to Burriy, and a Russian-English dictionary that he had used for practising his English.[8][14][15] Burriy managed to avoid capture during the search and until the end of the war.[12]

Gould was arrested by the Nazis and charged. At trial she was sentenced to two years in prison for harbouring Burriy, and for the possession of a radio which she had kept despite regulations requiring her to hand it in.[6] Arrested with her were her brother Harold Le Druillenec, and her sister Ivy Forster.[6]

Following her trial, Gould was sent to the Ravensbrück concentration camp. Her brother Harold Le Druillenec was sent to the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, and would be one of only two British survivors.[16] Louisa Gould was gassed to death in February 1945 at Ravensbrück, two months before liberation.[17]

Recognition

In 1995[18] a memorial plaque was unveiled in St Ouen, Jersey; Burriy, the former Russian slave, attended its unveiling.[19][8] In 2010 she was posthumously named a British Hero of the Holocaust.[20][21][22] Gould's story is depicted in the 2017 film Another Mother's Son by Jenny Seagrove.[16][17][23]

References

- In Another Mother's Son, between the end of the story and the start of the cast list, there are a few frames with photos and details of the main characters and what happened to them after the point at which the story in the film ends. The details for Louisa Gould give her precise date of death: 13 February 1945. (Viewed on DVD, where there was time to note this.)

- "The true story of Louisa Gould". Jersey Tourist Information Centre. 14 March 2017. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- Paul Sanders (1998). The ultimate sacrifice: the Jersey Twenty and their "offenses against the occupying authorities", 1940–1945. Jersey Museums Service.

- Société jersiaise (1999). Annual bulletin.

- Barry Turner (25 April 2011). Outpost of Occupation: The Nazi Occupation of the Channel Islands 1940–45. Aurum Press. pp. 165–. ISBN 978-1-84513-724-3.

- Lyn Smith (5 January 2012). Heroes of the Holocaust: Ordinary Britons who risked their lives to make a difference. Ebury Publishing. pp. 103–. ISBN 978-1-4481-1812-0.

- "Archives and collections online". Jerseyheritage.org. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- Sturgis, India (19 March 2017). "Mourning her own son, the mother who hid a Russian PoW from Nazi occupiers, and made the ultimate sacrifice". Telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved 22 November 2017.

- Glynis Cooper (2008). Foul Deeds and Suspicious Deaths in Jersey. Casemate Publishers. pp. 161–. ISBN 978-1-84563-068-3.

- Carpenter, Julie (5 November 2012). "John Nettles: 'Telling the truth about Channel Islands cost me my friends'". Express.co.uk. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- "People of the Occupation – Jersey War Tunnels". Archived from the original on 2 September 2017. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- Gilly Carr; Paul Sanders; Louise Willmot (19 June 2014). Protest, Defiance and Resistance in the Channel Islands: German Occupation, 1940–45. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 195–. ISBN 978-1-4725-0813-3.

- Paul Sanders (2005). The British Channel Islands Under German Occupation, 1940–1945. Paul Sanders. pp. 130–. ISBN 978-0-9538858-3-1.

- Madeline Bunting (24 July 2014). The Model Occupation: The Channel Islands Under German Rule, 1940–1945. Random House. pp. 209–. ISBN 978-1-4735-2130-8.

- Peter Tabb (2005). A Peculiar Occupation: New Perspectives on Hitler's Channel Islands. Ian Allan. ISBN 978-0-7110-3113-5.

- Bruxelles, Simon de. "Stars bring story of Jersey heroine gassed by Nazis to big screen". The Times. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- "Major film to tell the story of Jersey heroine's bravery". Jersey Evening Post. Archived from the original on 17 March 2017. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- "Archives and collections online". Catalogue.jerseyheritage.org. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- David W. Moore (8 November 2005). The Other British Isles: A History of Shetland, Orkney, the Hebrides, Isle of Man, Anglesey, Scilly, Isle of Wight and the Channel Islands. McFarland. pp. 239–. ISBN 978-0-7864-8924-4.

- Blake, Heidi (10 March 2010). "The remarkable stories of Britain's Heroes of the Holocaust". Archived from the original on 1 December 2016. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- "Gordon Brown honours British Holocaust heroes". Thejc.com. Retrieved 3 November 2021.

- "Courage of four Island heroes". Jersey Evening Post. Archived from the original on 17 March 2017. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- "Date set for Occupation-based film premiere". Bailiwickexpress.com. Retrieved 17 March 2017.