Puffadder shyshark

The puffadder shyshark (Haploblepharus edwardsii), also known as the Happy Eddie, is a species of catshark, belonging to the family Scyliorhinidae, endemic to the temperate waters off the coast of South Africa. This common shark is found on or near the bottom in sandy or rocky habitats, from the intertidal zone to a depth of 130 m (430 ft). Typically reaching 60 cm (24 in) in length, the puffadder shyshark has a slender, flattened body and head. It is strikingly patterned with a series of dark-edged, bright orange "saddles" and numerous small white spots over its back. The Natal shyshark (H. kistnasamyi), formally described in 2006, was once considered to be an alternate form of the puffadder shyshark.

| Puffadder shyshark | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Chondrichthyes |

| Order: | Carcharhiniformes |

| Family: | Scyliorhinidae |

| Genus: | Haploblepharus |

| Species: | H. edwardsii |

| Binomial name | |

| Haploblepharus edwardsii (Schinz, 1822) | |

| |

| Range of the puffadder shyshark | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Scyllium edwardsii Schinz, 1822 | |

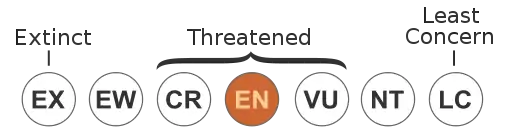

When threatened, the puffadder shyshark (and other members of its genus) curls into a circle with its tail covering its eyes, giving rise to the local names "shyshark" and "doughnut". It is a predator that feeds mainly on crustaceans, polychaete worms, and small bony fishes. This shark is oviparous and females deposit egg capsules singly or in pairs onto underwater structures. Harmless to humans, the puffadder shyshark is usually discarded by commercial and recreational fishers alike for its small size. It has been assessed as endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), as its entire population is located within a limited area and could be affected by a local increase in fishing pressure or habitat degradation.

Taxonomy and phylogeny

The first known reference to the puffadder shyshark in literature was by prominent English naturalist George Edwards in 1760, by the name Catulus major vulgaris,[2] of three individuals caught off the Cape of Good Hope that have since been lost. In 1817, French zoologist Georges Cuvier described this species as "Scyllium D'Edwards", based on Edwards' account, though he was not considered to be proposing a true scientific name. In 1832, German zoologist Friedrich Siegmund Voigt translated Cuvier's description under the name Scyllium edwardsii, thus receiving attribution for the species. However, in 2001 M.J.P. van Oijen discovered that Swiss naturalist Heinrich Rudolf Schinz had provided an earlier translation of Cuvier's text with the proper scientific name in 1822, and subsequently the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN) rendered a decision that this species is properly attributed to Schinz.[3][4][5] In 1913, American zoologist Samuel Garman created the new genus Haploblepharus for this and other shyshark species.[6]

Two forms of puffadder shyshark were once recognized: "Cape" and "Natal", which differed in appearance and habitat preferences. In 2006, the "Natal" form was described as a new species, the Natal shyshark.[7] A 2006 phylogenetic analysis, based on three mitochondrial DNA genes, found that the puffadder shyshark is the most basal member of its family, with a sister relationship to the clade containing the dark shyshark (H. pictus) and the brown shyshark (H. fuscus). The Natal shyshark was not included in the study, though it is very close morphologically to this species.[8] The common name "puffadder shyshark" refers to the puff adder (Bitis arietans), a widely distributed African viper with similar coloration.[9] "Happy Eddie" (from the scientific name Haploblepharus edwardsii) is used by academics for this shark, and was recently introduced to the public as an easily remembered alternative to the ambiguous vernaculars "shyshark" and "doughnut", which can apply to several different species and have confounded research efforts.[5]

Description

The puffadder shyshark is more slender than other shysharks, with a short, broad, dorsally flattened head and a narrowly rounded snout.[5] The large, oval-shaped eyes have cat-like slit pupils, a simple nictitating membrane (a protective third eyelid), and a prominent ridge underneath. The nostrils are very large, with a pair of greatly expanded, triangular flaps of skin in front that are fused together and reach the mouth. There is a deep groove connecting the excurrent (outflow) opening of each nostril to the mouth, obscured by the nasal flaps. The mouth is short with furrows at the corners on both jaws.[6] There are 26–30 tooth rows in the upper jaw and 27–33 tooth rows in the lower jaw. Tooth shape is sexually dimorphic: those of males are longer and three-pointed, while those of females are shorter and five-pointed.[10] Unusually, the two halves of the lower jaw are connected by a special cartilage, which allows a more even distribution of teeth and may increase bite strength.[11]

The five pairs of gill slits are positioned somewhat on the upper surface of the body. The dorsal, pelvic, and anal fins are all of similar size. The dorsal fins are located far back on the body, the first originating behind the pelvic fin origins and the second behind the anal fin origin. The pectoral fins are broad and of moderate size. The short, broad caudal fin comprises about one-fifth of the body length and has a deep ventral notch near the tip of the upper lobe and a barely developed lower lobe. The skin is thick and covered by well-calcified, leaf-shaped dermal denticles.[6] The dorsal coloration consists of a light to dark brown background with a series of 8–10 striking yellowish to reddish brown "saddles" with darker margins, all covered by a profusion of small white spots. The underside is white. This species attains a length of 60 cm (24 in), with a maximum record of 69 cm (27 in).[12] Sharks found west of Cape Agulhas are smaller than those found east, reaching only 48 cm (19 in) long.[5]

Distribution and habitat

The range of the puffadder shyshark is limited to the continental shelf along the coast of South Africa, from Langebaan Lagoon in Western Cape Province to the western shore of Algoa Bay. Previous records of it being found as far north as Durban are now thought to be misidentifications of other species.[5] This bottom-dwelling shark is most common over sandy or rocky bottoms. It is found in progressively deeper water towards the northeastern portion of its range, from 0–15 m (0–49 ft) off Cape Town to 40–130 m (130–430 ft) off KwaZulu-Natal; this distribution pattern may reflect this shark's preference for cooler waters.[6]

Biology and ecology

Quite common within its small range, the sluggish and reclusive puffadder shyshark is often seen lying still on the sea floor.[9][13] It is gregarious and several individuals may rest together.[12] A generalist predator with grasping dentition, the puffadder shyshark is known to take a variety of small benthic prey: crustaceans (including crabs, shrimp, crayfish, mantis shrimp, and hermit crabs), annelid worms (including polychaetes), bony fishes (including anchovies, jack mackerels, and gobies), cephalopods (including squid), and fish offal.[10] Overall, the most important component of this shark's diet is crustaceans, followed by polychaetes and then fishes. Males seem to prefer polychaetes, while females prefer crustaceans.[12][14] It has been observed attacking a common octopus (Octopus vulgaris) by tearing off an arm with a twisting motion.[15]

The puffadder shyshark is preyed upon by larger fishes, such as the broadnose sevengill shark (Notorynchus cepedianus).[16] The Cape fur seal (Arctocephalus pusillus pusillus) has been documented capturing and playing with puffadder shysharks, tossing them into the air or gnawing on them. The shark is often injured or killed during these encounters; the seal may eat torn-off pieces of flesh, but seldom consumes the entire shark. On occasion, black-backed kelp gulls (Larus dominicanus vetula) take advantage of this behavior and steal the sharks from the seals.[17] When threatened or disturbed, the puffadder shyshark adopts a characteristic posture in which it curls into a ring and covers its eyes with its tail; this reaction is the basis for the common names "shyshark" and "doughnut", and is likely meant to make the shark harder for a predator to swallow.[5][12]

The eggs of the puffadder shyshark are fed upon by the whelks Burnupena papyracea and B. lagenaria, at least in captivity.[18] Known parasites of this species include the trypanosome Trypanosoma haploblephari, which infests the blood,[19] the nematode Proleptus obtusus, which infests the intestine,[20] and the copepods Charopinus dalmanni and Perissopus oblongatus, which infest the skin.[21] Another parasite is the praniza larval stage of the isopod Gnathia pantherina, which infests the nares, mouth, and gills. The deep-penetrating mouthparts of these larvae significantly damage local tissue, causing bleeding and inflammation.[22]

Life history

The puffadder shyshark is oviparous; there is no distinct breeding season and reproduction occurs year-round.[14] Females deposit egg capsules one or two at a time, attaching them to vertical structures such as sea fans.[12] The thin-walled egg cases are brown with distinctive pale transverse bands; and have a slightly furry texture and long adhesive tendrils at the corners. They are smaller than those of other shyshark species, measuring 3.5–5 cm (1.4–2.0 in) long and 1.5–3 cm (0.59–1.18 in) across.[11][23] The young shark hatches after three months, and measures around 9 cm (3.5 in) long.[1] The length at maturation for both sexes has been reported as anywhere from 35 to 55 cm (14 to 22 in) by various sources; this high degree of variation may reflect regional differences as sharks from deeper waters in the eastern part of its range seem to mature at a larger size than those from the west.[5] The age at maturation is estimated to be around 7 years, and the maximum lifespan is at least 22 years.[14]

Human interactions

Harmless to humans, the puffadder shyshark can be easily caught by hand.[24] Not targeted by commercial fisheries because of its small size, it is taken incidentally and discarded by bottom trawlers operating between Mossel Bay and East London, and by fishing boats in False Bay. Many are hooked by recreational anglers casting from the shore, who also generally discard or kill them as minor pests.[11] Some local exploitation of this species does occur for lobster bait and the aquarium trade. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has assessed the puffadder shyshark as endangered. The small range of this shark lies entirely within a heavily fished region, and any increase in fishing activities or habitat degradation could potentially impact the entire population.[24]

References

- Pollom, R.; Da Silva, C.; Gledhill, K.; Leslie, R.; McCord, M.E.; Winker, H. (2020). "Haploblepharus edwardsii". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T39345A124403633. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-2.RLTS.T39345A124403633.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- Edwards, George (1760). Gleanings of Natural History, exhibiting figures of quadrupeds, birds, insects, plants &c... (in English and French). Vol. Part 2. London: Printed for the author, at the College of Physicians. pp. 169–170, Plate 289.

- Schinz, Heinrich Rudolf (1822). Das Thierreich eingetheilt nach dem Bau der Thiere als Grundlage ihrer Naturgeschichte und der vergleichenden Anatomie (in German). Vol. 2. Stuttgart und Tübingen: in der J.G. Cotta'schen Buchhandlung. p. 214, Footnote.

- International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature (2003). "Opinion 2056 (Case 3186). Squalus edwardsii (currently Haploblepharus edwardsii; Chondrichthyes, Carcharhiniformes): attributed to Schinz, 1822 and edwardsii conserved as the correct original spelling of the specific name". Bulletin of Zoological Nomenclature. 60 (3): 250.

- Human, B.A. (2007). "A taxonomic revision of the catshark genus Haploblepharus Garman 1913 (Chondrichthyes: Carcharhiniformes: Scyliorhinidae)". Zootaxa. 1451: 1–40. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.1451.1.1.

- Compagno, L.J.V. (1984). Sharks of the World: An Annotated and Illustrated Catalogue of Shark Species Known to Date. Rome: Food and Agricultural Organization. pp. 332–333. ISBN 978-92-5-101384-7.

- Human, B.A. & Compagno, L.J.V. (2006). "Description of Haploblepharus kistnasamyi, a new catshark (Chondrichthyes: Scyliorhinidae) from South Africa". Zootaxa. 1318: 41–58. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.1318.1.2.

- Human, B.A.; E.P. Owen; L.J.V. Compagno & E.H. Harley (May 2006). "Testing morphologically based phylogenetic theories within the cartilaginous fishes with molecular data, with special reference to the catshark family (Chondrichthyes; Scyliorhinidae) and the interrelationships within them". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 39 (2): 384–391. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2005.09.009. PMID 16293425.

- Ferrari, A. & A. Ferrari (2002). Sharks. Firefly Books. p. 131. ISBN 978-1552096291.

- Bester, C. Biological Profiles: Puffadder Shyshark Archived 2012-05-24 at the Wayback Machine. Florida Museum of Natural History Ichthyology Department. Retrieved on August 31, 2009.

- Van der Elst, R. (1993). A Guide to the Common Sea Fishes of Southern Africa (third ed.). Struik. p. 71. ISBN 978-1-86825-394-4.

- Compagno, L.J.V.; M. Dando & S. Fowler (2005). Sharks of the World. Princeton University Press. pp. 234–235. ISBN 978-0-691-12072-0.

- Heemstra, E. & P. Heemstra (2004). Coastal Fishes of Southern Africa. NISC and SAIAB. p. 67. ISBN 978-1-920033-01-9.

- Dainty, A.M. (2002). Biology and ecology of four catshark species in the southwestern Cape, South Africa. M.Sc. thesis, University of Cape Town.

- Lechanteur, Y.A.R.G. & C.L. Griffiths (October 2003). "Diets of common suprabenthic reef fish in False Bay, South Africa". African Zoology. 38 (2): 213–227.

- Ebert, D.A. (December 1991). "Diet of the seven gill shark Notorynchus cepedianus in the temperate coastal waters of southern Africa". South African Journal of Marine Science. 11 (1): 565–572. doi:10.2989/025776191784287547.

- Martin, R.A. (2004). "Natural mortality of puffadder shysharks due to Cape fur seals and black-backed kelp gulls at Seal Island, South Africa". Journal of Fish Biology. 64 (3): 711–716. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8649.2004.00339.x.

- Smith, C. & C. Griffiths (1997). "Shark and skate egg-cases cast up on two South African beaches and their rates of hatching success or causes of death". South African Journal of Zoology. 32 (4): 112–117. doi:10.1080/02541858.1997.11448441.

- Yeld, E.M. & N.J. Smit (2006). "A new species of Trypanosoma (Kinetoplastida: Trypanosomatidae) infecting catsharks from South Africa". Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. 86 (4): 829–833. doi:10.1017/S0025315406013750. S2CID 86498165.

- Moravec, F.; J.G. Van As & I. Dykova (November 2002). "Proleptus obtusus Dujardin, 1845 (Nematoda: Physalopteridae) from the puffadder shyshark Haploblepharus edwardsii (Scyliorhinidae) from off South Africa". Systematic Parasitology. 53 (3): 169–173. doi:10.1023/A:1021130825469. PMID 12510161. S2CID 22873948.

- Dippenaar, S.M. (2004). "Reported siphonostomatoid copepods parasitic on marine fishes of southern Africa". Crustaceana. 77 (11): 1281–1328. doi:10.1163/1568540043165985.

- Hayes, P.M.; N.J. Smit & A.J. Davies (2007). "Pathology associated with parasitic juvenile gnathiids feeding on the puffadder shyshark, Haploblepharus edwardsii (Voight)". Journal of Fish Diseases. 30 (1): 55–58. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2761.2007.00777.x. PMID 17241405.

- Smith, C. & C. Griffiths (October 1997). "Shark and skate egg-cases cast up on two South African beaches and their rates of hatching success, or causes of death". South African Journal of Zoology. 32 (4): 112–117. doi:10.1080/02541858.1997.11448441.

- Fowler, S.L.; R.D. Cavanagh; M. Camhi; G.H. Burgess; G.M. Cailliet; S.V. Fordham; C.A. Simpfendorfer & J.A. Musick (2005). Sharks, Rays and Chimaeras: The Status of the Chondrichthyan Fishes. International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources. p. 265. ISBN 978-2-8317-0700-6.

External links

Media related to Haploblepharus edwardsii at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Haploblepharus edwardsii at Wikimedia Commons- 3D animation of a Puffadder shyshark