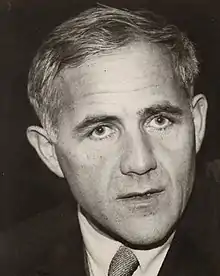

Hannes Meyer

Hans Emil "Hannes" Meyer (18 November 1889 – 19 July 1954) was a Swiss architect and second director of the Bauhaus Dessau from 1928 to 1930.

Hannes Meyer | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Hans Emil Meyer 18 November 1889 |

| Died | 19 July 1954 (aged 64) |

Early life

Meyer was born in Basel, Switzerland, trained as a mason, and practiced as an architect in Switzerland, Belgium, and Germany. From 1916 to 1918, he briefly served as a department manager at the Krupp works in Essen.[1]

Early work

Between 1919 and 1921, Meyer completed planning the housing estate "Freidorf" near the Swiss city of Basel.

In 1923, Meyer co-initiated the architectural magazine 'ABC Beiträge zum Bauen' (Contributions on Building) with Hans Schmidt, Mart Stam, and the Suprematist El Lissitzky in Zurich.

Meyer's design philosophy is represented by the following quote:

"1. sex life, 2. sleeping habits, 3. pets, 4. gardening, 5. personal hygiene, 6. weather protection, 7. hygiene in the home, 8. car maintenance, 9. cooking, 10. heating, 11. exposure to the sun, 12. services - these are the only motives when building a house. We examine the daily routine of everyone who lives in the house and this gives us the functional diagram - the functional diagram and the economic programme are the determining principles of the building project."(Meyer, 1928)[2]

In 1926, Meyer established a company with Hans Wittwer and produced his two most famous designs, for the Basel Petersschule (1926) and for the Geneva League of Nations Building (1926/1927).[1] Both projects are strict, inventive, and rely on the new possibilities of structural steel. Neither was built. The Petersschule was designed to be a new primary school for girls, such that the school itself would be raised as high above the ground as possible to allow for sunlight and fresh air.[3]

Bauhaus

Walter Gropius appointed Meyer director of the Bauhaus architecture department when it was finally established during April 1927, though Mart Stam had been Gropius's first choice. Meyer brought his radical functionalist philosophy which he named, during 1929, Die neue Baulehre (the new way to build).[4] His philosophy was that architecture was an organizational task without relationship to aesthetics, that buildings should be low cost and designed to fulfill social needs. He was dismissed for allegedly politicizing the school.

Meyer brought the two most significant building commissions for the school, both of which still exist. One was a complex of five apartment buildings in the city of Dessau known as Laubenganghäuser ("Houses with Balcony Access"). The apartments are considered to be 'real' Bauhaus buildings because they originated with the Bauhaus department of Architecture. The development bordered on the Törten housing estate [5] which was designed by Walter Gropius.[6]

The other major building commission was the Bundesschule des Allgemeinen Deutschen Gewerkschaftsbundes (ADGB Trade Union School), in Bernau bei Berlin, which was completed during 1930. It was the second largest project ever undertaken by the Bauhaus, after the Bauhaus school buildings in Dessau.[7][8][9] The school operated for only three years until the Nazis confiscated it during 1933 for use as a management training school. The building now has historic protection status and it experienced an extensive restoration which was completed during 2007. The restoration project won the World Monuments Fund / Knoll Modernism prize during 2008.

In July 2017, both the Laubenganghäuser and the ADGB Trade Union School were inscribed as part of the Bauhaus and its Sites in Weimar, Dessau and Bernau World Heritage Site.[10]

Walter Gropius appointed Meyer to replace him as the school's director on 1 April 1928.[11] Meyer continued with Gropius' innovations to emphasize designing prototypes for serial mass production and functionalist architecture. In the increasingly dangerous political era of the Weimar Republic, Dessau's Mayor, Hesse, alleged that Meyer allowed a Communist student organization to flourish and bring bad publicity to the school, threatening its survival. Hesse dismissed Meyer as head of the Bauhaus school, with a monetary settlement, on 1 August 1930.[12] Meyer's open letter in a left-wing newspaper two weeks later characterizes the Bauhaus as "Incestuous theories (blocking) all access to healthy, life-oriented design... As head of the Bauhaus, I fought the Bauhaus style".[13]

Career in the Soviet Union

In the autumn of 1930, Meyer emigrated to the Soviet Union, along with several former Bauhaus students, including Konrad Püschel and Philipp Tolziner. He taught at WASI, a Soviet academy for architecture and civil engineering. During his years in the Soviet Union, he acted as an advisor for urban projects at Giprogor (the Soviet Institute for Urban and Investment Development) and created plans related to aspects of the redevelopment of Moscow as part of the first five-year plan.[14]

Outside Moscow, Meyer realised his ideas especially in the recently created Jewish Autonomous Oblast in the Soviet Far East. Meyer not only realised the buildings (such as worker's dormitory, theatre etc.) and their internal design and furnishings but also developed the urbanist project for the area's capital, the city of Birobidzhan.[15]

Meyer fell increasingly out of favour with the Stalinist authorities from 1933 onwards. The first so-called "purges" also began within the large Moscow community of foreigners. Meyer therefore returned to Geneva in his Swiss homeland in 1936. Margarete Mengel, his partner and mother of his son, as a German citizen, was not granted a visa and therefore remained in Moscow with their son. Margarete was arrested in 1938 and sentenced to death by administrative means along with many other foreigners. The execution by firing squad took place on 20 August 1938. The son Johannes Mengel, born 4 January 1927, survived in a state reformatory and only learned of his mother's violent death in 1993.

Career in Mexico

In 1939 Meyer emigrated to Mexico City to work for the Mexican government as the director of the Instituto del Urbanismo y Planificación from 1939 through 1941. In 1942, he became the director of Estampa Mexicana, the publishing house of the Taller de Gráfica Popular (the Popular Graphic Arts Workshop).

Death and legacy

Meyer returned to Switzerland in 1949 and died in 1954.

References

- Bauhaus, 1919-1933, by Magdalena Droste, Bauhaus-Archiv, page 248

- Theo Van Leeuwen, "Introducing Social Semiotics", Routledge, 2004, p.71

- Claude Schnaidt, Hannes Meyer: Buildings, projects, and writings (New York: Architecture Book Publishing, 1965).

- Hannes Mayer, "bauhaus und gesellschaft" (1929), cf. Wilma Ruth Albrecht: "Moderne Vergangenheit - Vergangene Moderne" (Neue Politische Literatur, 30 [1985] 2, pp. 203-225, esp. pp. 210-214)

- Bauhaus Dessau: Törten estate by Walter Gropius (Accessed: 27 October 2016)

- Architectuul: Laubenganghäuser Dessau (2015) Archived 2012-11-18 at the Wayback Machine (Accessed: 27 October 2016).

- The Bauhaus building by Walter Gropius (1925-26) (Accessed: 21 October 2016)

- Internat der Handwerkskammer Berlin in Bernau Archived 2016-11-05 at the Wayback Machine (Photos with German text) (Accessed: 21 October 2016).

- Architectuul: ADGB trade union school (2013) (Accessed: 27 October 2016).

- "Bauhaus and its Sites in Weimar, Dessau and Bernau". UNESCO. Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- Bauhaus100. Hannes Meyer (Accessed: 6 February 2017)

- Richard A. Etlin editor, Art, culture, and media under the Third Reich, page 291, ISBN 0-226-22087-7 ISBN 978-0-226-22087-1 On Meyer and the Communist students, see Cimino, Eric. Student Life at the Bauhaus, 1919-1933. M.A. Thesis, UMass-Boston, 2003, pp. 82-87.

- Bauhaus, 1919-1933, by Magdalena Droste, Bauhaus-Archiv, page 199

- Talesnik, Daniel (2016)The Itinerant Red Bauhaus, or the Third Emigration. PhD Thesis in Architectural History and Theory, Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation, Columbia University, New York in ABE Journal (Architecture Beyond Europe), volume 11, 2017. Retrieved 12 April 2019

- "Hannes Meyer and the Red Bauhaus-Brigade in the Soviet Union (1930-1937)". thecharnelhouse.org. 30 May 2013. Retrieved 2014-05-10.