Gustavians

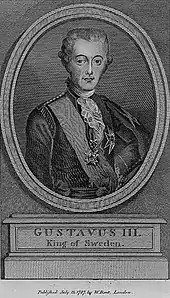

The Gustavians (Swedish: Gustavianerna) were a political faction in the Kingdom of Sweden who supported the absolutist regime of King Gustav III of Sweden, and sought after his assassination in 1792 to uphold his legacy and protect the interests of his descendants of the House of Holstein-Gottorp.

The term can also be used in a looser sense to refer to Swedes generally during the Gustavian era (i.e. the reigns of Gustav III and his son Gustav IV Adolf), in the same way that the word "Victorians" is used of Britons during the reign of Queen Victoria.

The Gustavian Party

Under Gustav III

The original Gustavians were the men who supported King Gustav III’s self-coup, the Revolution of 1772, and his institution of an absolute monarchy under the Instrument of Government (1772), replacing the constitutional monarchy of the Age of Liberty (1719-72). They thus represented a continuation of the Court Party which had agitated for a stronger monarchy during the Age of Liberty. Prominent Gustavians in this early stage included Jacob Magnus Sprengtporten and Johan Christopher Toll, the two leaders of the coup besides Gustav himself.

Having seized power, Gustav governed Sweden with the aid of a small circle of favourites and close advisors, among them Toll, Elis Schröderheim, Hans Henric von Essen, Carl Gustaf Nordin and Gustaf Mauritz Armfelt.[1] Ironically, Armfelt’s uncle Carl Gustaf Armfeldt the Younger was a vehement opponent of the king, and was a leading member of the 1788 Anjala Conspiracy against him.[2]

Under Gustav IV Adolf

Gustav III was assassinated in March 1792, whereupon his son became King Gustav IV Adolf. As he was underage, a regency government was established to govern Sweden on his behalf. Officially the regency was headed by the king’s uncle, Gustav III’s younger brother Duke Charles of Södermanland, but he was largely uninterested in politics and so it came to be dominated instead by the duke’s friend Gustaf Adolf Reuterholm. Reuterholm had long been hostile to Gustav III (indeed he had been implicated in the abortive 1789 Conspiracy against the late king), and promptly set about reversing many of his policies, most famously by restoring the freedom of the press, which Gustav had curtailed.

_p041_G.M._Armfelt.jpg.webp)

The Gustavians strongly opposed Reuterholm, and a number of them were involved in the 1793 Armfelt Conspiracy, which sought to remove Duke Charles as regent and replace him with Gustaf Mauritz Armfelt. Reuterholm used the exposure of this plot as an excuse to have several leading Gustavians arrested and to marginalise the others; Armfelt himself escaped into exile.[3]

Fortunately for the Gustavians, Gustav Adolf himself shared their horror at Reuterholm’s trampling on his father’s legacy, and when he came of age in 1796 he immediately sent Reuterholm into exile and appointed a number of old Gustavians as his ministers, foremost among them Armfelt.[4] Another prominent advisor to the young king was the Marshal of the Realm, Axel von Fersen the Younger, who had spent much of Gustav III’s reign in France, at the court of Louis XVI, but had been forced to return to Sweden by the French Revolution.[5]

Gustav III had been a fervent opponent of the French Revolution, and Gustav Adolf upheld these reactionary principles by joining the Third Coalition against Napoleonic France. This proved to be a fatal misjudgement. In 1806-7 Napoleon conquered Swedish Pomerania, the last surviving relic of the Swedish Empire, and in 1809 the Russian Empire switched sides and formed an alliance with France against Sweden. In the resulting Finnish War (1808-9), Russian forces rapidly overran the entirety of Finland, which had been Swedish for six hundred years and was (unlike Pomerania and the other overseas territories of the former Swedish Empire) considered to be an intrinsic part of the Kingdom of Sweden. Its loss was therefore hugely traumatic for the Swedish political community, and represented a fatal blow to Gustav Adolf’s authority. In March 1809, a Swedish army commanded by Georg Adlersparre mutinied, triggering the Coup of 1809, in which Gustav Adolf was forced to abdicate and sent into exile, Duke Charles was declared king, and constitutional monarchy was restored by the Instrument of Government (1809).

Under Charles XIII

Some Gustavians could not reconcile themselves to the new regime, among them Armfelt, who retired to the now Russian-ruled Grand Duchy of Finland. However, the majority of them stayed in Sweden, most notably Fersen, who remained in post as Marshal of the Realm and thereby retained a seat on the Council of the Realm.

The new King Charles XIII was elderly and childless, and as such his hereditary heir was his great-nephew Prince Gustav, 10-year-old son of the deposed Gustav Adolf. However, Adlersparre and his supporters were concerned that Gustav Vasa would resent his father’s overthrow in the same way that Gustav Adolf himself had resented the Reuterholm regency, and worried that if he became king he might even try to mount his own coup and restore absolutism in the same way that Gustav III had done in 1772. The constitutionalists therefore persuaded the Riksdag of the Estates (Swedish parliament) to pass a resolution on 10 May 1809 excluding Gustav Adolf and all his descendants from the Swedish order of succession in perpetuity.[6]

Instead, it was decided that the king should adopt an outsider as his heir. The choice was put to the Riksdag, which voted for the Danish prince Charles August. However, for various reasons Charles August was unable to come to Sweden to be formally invested as crown prince for several months, and in the meantime the Gustavians plotted a coup of their own, intending to get rid of the 1809 Instrument of Government, restore absolutism and have Prince Gustav formally recognised as heir to the throne. In this they were supported by monarchists who were upset with the idea of interfering with the principle of hereditary succession, including King Charles himself and his wife Queen Charlotte. However, the plans failed to come to fruition before Charles August’s arrival in January 1810.[7]

Once in Sweden, the new crown prince tried to win over the Gustavians by secretly offering to adopt Prince Gustav as his own heir,[8][9] he being childless himself. However, in May he suddenly dropped dead from a stroke, which led to rumours that he had been poisoned by the Gustavians, and during his funeral the unfortunate Fersen was publicly lynched by an enraged mob.

The Riksdag was therefore forced to choose an heir to the throne for the second time in as many years. The Gustavians campaigned vigorously on behalf of Prince Gustav, but in the end the decision went against them again, this time in favour of the French Marshal of the Empire Jean Baptiste Bernadotte. However, Bernadotte quickly managed to win over most of the Gustavians, in part because he shared their conservative views,[10][11] and by the time he ascended the throne in 1818 (as King Charles XIV John), the few remaining irreconcilables had faded into political irrelevance.

Other Uses of the Term

Soldiers of the Swedish army during the reigns of Gustav III and Gustav IV Adolf are sometimes referred to as “Gustavians”, just as their predecessors during the reigns of Charles XI and Charles XII are known as “Caroleans” (from Carolus, the Latin form of the name Charles). The term is used in this sense in the names of several historical reenactment groups specialising in this period, such as the Westgiötha Gustavianer (literally "Westrogothic Gustavians"). The main campaigns in which Gustavian soldiers fought were the Russo-Swedish War (1788-1790), the Franco-Swedish War and the Finnish War. Their uniforms, introduced in 1779 as part of Gustav III’s extensive military reform programme, are distinguished from those of earlier Swedish soldiers by their shorter jackets and the substitution of round plumed hats for the earlier tricorns.[12]

Artists active during the Gustavian era are also often referred to as Gustavians, especially those with links to the royal court, such as Johan Henric Kellgren, Carl Gustaf af Leopold, Gustaf Filip Creutz, Johan Gabriel Oxenstierna and Johan Tobias Sergel.[13]

See also

References

- "Gustavianerna". Nordisk Familjebok. 10: 700–1.

- "Carl Gustav Armfeldt". Svenskt Biografiskt Lexikon.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Bain, Robert Nisbet (1911). "Armfelt, Gustaf Mauritz". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 2 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- "Gustav IV Adolf". Svenskt Biografiskt Lexikon.

- "H Axel Fersen". Svenskt Biografiskt Lexikon.

- "Gustavianerna". Nordisk Familjebok. 10: 700–1.

- "Gustavianerna". Nordisk Familjebok. 10: 700–1.

- "Gustavianerna". Nordisk Familjebok. 10: 700–1.

- af Klercker, Cecilia, ed. (1939). Hedvig Elisabeth Charlottas dagbok [The diary of Hedvig Elizabeth Charlotte] (in Swedish). Vol. VIII 1807–1811. Translated by Cecilia af Klercker. Stockholm: P.A. Norstedt & Söners förlag. pp. 506–07.

- "Gustavianerna". Nordisk Familjebok. 10: 700–1.

- "Charles XIV John". Encyclopaedia Britannica.

- Markelius, Martin (2020). Gustav III:s armé. Stockholm: Medströms bokförlag.

- "Gustavianerna". Nordisk Familjebok. 10: 700–1.

Sources

- "Gustavianerna". Nordisk Familjebok. 10: 700–1.