Great uncial codices

The great uncial codices or four great uncials are the only remaining uncial codices that contain (or originally contained) the entire text of the Bible (Old and New Testament) in Greek. They are the Codex Vaticanus in the Vatican Library, the Codex Sinaiticus and the Codex Alexandrinus in the British Library, and the Codex Ephraemi Rescriptus in the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris.

Description

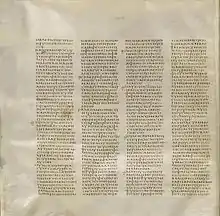

Only four great codices have survived to the present day: Codex Vaticanus (abbreviated: B), Codex Sinaiticus (ℵ), Codex Alexandrinus (A), and Codex Ephraemi Rescriptus (C).[1] Although discovered at different times and places, they share many similarities. They are written in a certain uncial style of calligraphy using only majuscule letters, written in scriptio continua (meaning without regular gaps between words).[1][2] Though not entirely absent, there are very few divisions between words in these manuscripts. Words do not necessarily end on the same line on which they start. All these manuscripts were made at great expense of material and labour, written on vellum by professional scribes.[3] They seem to have been based on what were thought to be the most accurate texts of their time.

All of the great uncials had the leaves arranged in quarto form.[4] The size of the leaves is much larger than in papyrus codices:[5][6]

- B: Codex Vaticanus – 27 × 27 cm (10.6 × 10.6 in); c. 325–350

- ℵ: Codex Sinaiticus – 38.1 × 34.5 cm (15.0 × 13.6 in); c. 330–360

- A: Codex Alexandrinus – 32 × 26 cm (12.6 × 10.4 in); c. 400–440

- C: Codex Ephraemi – 33 × 27 cm (13.0 × 10.6 in); c. 450

- D: In the 19th century, the Codex Bezae was also included to the group of the great uncials (F. H. A. Scrivener, Dean Burgon).

Codex Vaticanus uses the oldest system of textual division in the Gospels. Sinaiticus, Alexandrinus, and Ephraemi have the Ammonian Sections with references to the Eusebian Canons. Codex Alexandrinus and Ephraemi Rescriptus use also a division according to the larger sections – κεφάλαια (kephalaia, chapters). Alexandrinus is the earliest manuscript which uses κεφάλαια.[7] Vaticanus has a more archaic style of writing than the other manuscripts. There is no ornamentation or any larger initial letters in Vaticanus and Sinaiticus, but there is in Alexandrinus. Vaticanus has no introduction to the Book of Psalms, which became a standard after 325 AD, whereas Sinaiticus and Alexandrinus do. The orders of their books differ.[8]

According to Burgon, the peculiar wording in some passages of the five great uncials (ℵ A B C D) shows that they were the byproduct of heresy–a position strongly contested by Daniel B. Wallace.[9]

Alexandrinus was the first of the greater manuscripts to be made accessible to scholars.[10] Ephraemi Rescriptus, a palimpsest, was deciphered by Tischendorf in 1840–1841 and published by him in 1843–1845.[11] Codex Ephraemi has been the neglected member of the family of great uncials.[12]

Sinaiticus was discovered by Tischendorf in 1844 during his visit to Saint Catherine's Monastery in Sinai. The text of the codex was published in 1862.[13] Vaticanus has been housed at the Vatican Library at least since the 15th century, but it became widely available after a photographic facsimile of the entire manuscript was made and published by Giuseppe Cozza-Luzi in 1889–1890 (in three volumes).[14]

It has been speculated that Codex Sinaiticus and Codex Vaticanus were part of a project ordered by Emperor Constantine the Great to produce 50 copies of the Bible.[15]

References

- Edward Ardron Hutton and Francis Crawford Burkitt, An atlas of textual criticism: being an attempt to show the mutual relationship of the authorities for the text of the New Testament up to about 1000 A.D., University Press, 1911.

- "Paleography Greek Writing". Archived from the original on 2017-08-02. Retrieved 2011-08-08.

- B. L. Ullman, Ancient Writing and Its Influence (1932)

- Falconer Madan, Books in Manuscript: a Short Introduction to their Study and Use. With a Chapter on Records, London 1898, p. 73.

- Roberts, C. H.; Skeat, T. C. (1983) [1954]. The Birth of the Codex. Oxford University Press for The British Academy. ISBN 0197260616. For online version see here at U Penn website.

- Parker, D. C. (2008). An Introduction to the New Testament Manuscripts and their Texts. Cambridge University Press. p. 71. ISBN 1139473107.

- Greg Goswell, Early Readers of the Gospels: The Kephalaia and Titloi of Codex Alexandrinus, JGRChJ 66 (2009), p. 139.

- Barry Setterfield, The Alexandrian Septuagint History, March 2010.

- Wallace, Daniel B. (1996). Greek Grammar Beyond the Basics: An Exegetical Syntax of the New Testament. HarperCollins. p. 455 (n. 31). ISBN 0310218950. Retrieved 17 March 2022.

- Kenyon, Frederick G. (1939). Our Bible and the Ancient Manuscripts (4th ed.). London: British Museum. p. 132.

- C. v. Tischendorf, Codex Ephraemi Syri rescriptus, sive Fragmenta Novi Testamenti, Lipsiae 1843–1845.

- Robert W. Lyon, New Testament Studies, V (1958–9), pp. 266–272.

- Constantin von Tischendorf: Bibliorum codex Sinaiticus Petropolitanus. Giesecke & Devrient, Leipzig 1862.

- Eberhard Nestle and William Edie, "Introduction to the Textual Criticism of the Greek New Testament", London, Edinburg, Oxford, New York, 1901, p. 60.

- Metzger, Bruce M.; Ehrman, Bart D. (2005). The Text of the New Testament: Its Transmission, Corruption, and Restoration (4th ed.). New York – Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 15–16.