Grayling (butterfly)

The grayling or rock grayling (Hipparchia semele) is a species in the brush-footed butterfly family Nymphalidae.[1] Although found all over Europe, the grayling mostly inhabits coastal areas, with inland populations declining significantly in recent years.[1][2] The grayling lives in dry and warm habitats with easy access to the sun, which helps them with body temperature regulation.[1][2]

| Grayling | |

|---|---|

| |

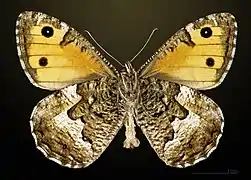

| Female | |

_male.jpg.webp) | |

| male, Portugal | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Lepidoptera |

| Family: | Nymphalidae |

| Genus: | Hipparchia |

| Species: | H. semele |

| Binomial name | |

| Hipparchia semele | |

A grayling goes through four stages in its life cycle. The eggs hatch around August, and larvae grow in four instars from August to the following June. By June, the larvae begin to pupate by spinning a silk cocoon below the surface of the ground. The adult grayling emerges around August.[1] The grayling migrates in small groups of two or three butterflies throughout most of August, typically moving southeast.[3]

H. semele engages in cryptic coloring, with their tan and brown colored wings helping them camouflage into their surroundings. The grayling exposes the eyespots on its wings when it believes to have been detected by a predator, but generally keeps them hidden to avoid being seen.[4] Male butterflies are territorial, and engage in flight performances to determine who settles in the best oviposition site.[5] Additionally, the grayling regulates its body temperature by orienting its body and posture to adjust to the heat from the sun.[2]

Grayling populations have recently begun to decline, and while it is not globally endangered, the species is now considered a priority for conservation efforts in the United Kingdom.[1]

Geographic range

Hipparchia semele lives at elevations between sea level and about 2,000 metres (6,600 ft).[1] The grayling is a species endemic to Europe, and is found almost all over Europe and parts of western Russia. In parts of northern and western Europe, including Scandinavia, Britain, Ireland, and the Baltic states, it can be seen mostly in the coastal areas.[1] The butterfly population is declining in many areas, especially inland.[2] The grayling is not found in west France, large parts of Greece, Albania, North Macedonia, and south of Bulgaria and the Mediterranean islands.[1]

Description in Seitz

S. semele L. (42 f). The female above similar to the preceding [ anthe ie. dark brown with a yellow-orange submarginal band marked in the female, more discreet in the male, with an interrupted fringe and two black blind or very discreetly pupiled ocelli on the forewing and a very small ocellus on the hindwing. The verso of the forewing is yellow-orange surrounded by a marbled band of brown and white with the two black ocelli while the hindwing verso is marbled with brown and white.], but the bands above ivory-yellow, often obscured, especially on the hindwing. The male above almost entirely dark, the band being only perceptible on the hindwing in the form of a row of obsolete ochre-yellow spots. Both sexes show, on a pale ochre ground, before the anal angle a dark ocellus which occasionally is pupilled with white. The underside of the hindwing is marbled with dark, a pale powdering in the form of a band terminating the basal portion distally. this band protruding in a strong tooth below the cell towards the margin.[6]

Habitat

Grayling populations are typically found in dry habitats with warm climates to aid in their thermoregulatory behavior.[1][2] Often found in sand dunes, salt marshes, undercliffs, and clifftops in coastal regions, and heathlands, limestone pavements, scree and brownfield land in inland regions, but graylings are also known to inhabit old quarries, railway lines, and industrial areas.[2] Colonies typically develop around areas with little vegetation and bare, open ground, with spots of shelter and sun to help them regulate their body temperature.[2]

Food resources

Adult diet[2]

Hipparchia semele can be considered a specialist feeding species.[7] They tend to feed on the following plants:

- Bird's-foot Trefoil (Lotus corniculatus)

- Bramble (Rubus fruticosus)

- Carline thistle (Carlina vulgaris)

- Heather (Calluna vulgaris)

- Marjoram (Origanum vulgare)

- Red Clover (Trifolium pretense)

- Teasel (Dipsacus fullonum)

- Thistles (Cirsium spp. and Carduus spp.)

Parental care

Oviposition

Hipparchia semele sometimes lay their eggs on the green leaves that the larvae later feed on. Because the adult butterflies lay their eggs on the ground, the larvae can easily find the host plants to feed on. Therefore, laying eggs directly on host plants does not seem to be crucial for survival to adulthood.[8]

Life history

Life cycle

Note that information on this species applies to Great Britain and some details may not be consistent with the species in other parts of its range.

There is one generation per year. The eggs are laid from July to September singly, often on the food plant. H. semele eggs are white at first, but turn pale yellow as they develop. The egg stage generally lasts between two and three weeks.[1]

When the eggs hatch, the caterpillar grows slowly, feeding at night and typically hibernating during cold temperatures in a deep patch of grass.[1] The larvae are small and cream colored, and there are four moults.[1] The first-instar and second-instar larvae feed in mid-to-late summer and then hibernate, while still small, in the third instar, at the base of a tussock. Feeding then resumes in the spring and the last instar larvae are nocturnal, hiding in the base of grass tussocks during the day. These larval instars take place from August to June. By June, the larvae should be fully grown, and at this point the caterpillar spends most of its time basking in the sun on the bare ground or rocks.[2] The larvae are attracted to muddy puddles and sap from tree trunks.[1] When the time comes to pupate, the caterpillar spins a cocoon in the ground.

Pupation happens in a cavity lined with silk below the surface of the ground.[1] The pupa is unattached in an earth cell. The pupal stage lasts around four weeks. The pupa is formed from June to August and the adult butterflies emerge in August.

Egg

Egg Larva

Larva_female_underside_U%C4%8Dka.jpg.webp) H. s. semele female

H. s. semele female

Učka Nature Park, Croatia.jpg.webp)

Male

Male Male underside

Male underside Female

Female Female underside

Female underside

Larval host plants

- Sheep's-fescue (Festuca ovina)

- Red fescue (Festuca rubra)

- Bristle bent (Agrostis curtisii)

- Early hair-grass (Aira praecox)

- Tufted hair-grass (Deschampsia cespitosa)

- Marram (Ammophila arenaria)

- Upright brome (Bromus erectus)

- Slim-stem reed grass (Calamagrostis neglecta)

- Grey hair-grass (Corynephorus canescens)

- Cock's-foot (Dactylis glomerata)

- Couch grass (Elymus repens)

- Agropyron species

- Triticum species

Migration

The Hipparchia semele often migrates in small groups of two or three, generally at 10-11 kilometers per hour. The flight direction of these migrating grayling is direct and constant, notably because they do not pause or dart off into short flights. The grayling generally migrates in the southeast direction through most of August.[3]

Protective coloration and behavior

Cryptic and mimicking color and behavior

.jpg.webp)

Hipparchia semele engages in cryptic coloring, or camouflage that makes it difficult to see them when they are resting on the bare ground, tree trunks, rocks, etc.[2] Their tan and brown colored wings help them conceal themselves. Usually at rest and when not in flight, the butterflies keep their wings closed, with their forewings tucked behind their hindwings. This helps them conceal their eyespots and makes them appear smaller, further helping them camouflage to their environment.

Additionally, the forewing of a Hipparchia semele has one large and one small eyespot. When the grayling butterfly believes it may have been detected by a predator, it exposes these spots. However, there may be a balance between their cryptic coloring behavior and the exposure of their conspicuous eye spots. Exposing their spots may increase detectability by their predators. Therefore, at rest, the grayling adopts its cryptic coloring position, pulling its forewings down behind its hindwings in order to conceal the eyespots.[4]

Mating

Mate searching behavior

When it comes time to mate, male and female H. semele meet above a solitary tree in a wide and open area. This takes on many forms, from a tall tree in a heathland to bare patches of ground in sand dunes. The female lays her eggs on various fine-leaved grasses, including fescues, bents, and bromes, a few centimeters above the ground.[1]

Lekking

Male butterflies exhibit behaviors for defending territories. Females choose males based on the best territory for them to lay their eggs in. These territorial males engage in competitions of flight performances where the winning male settles in the territory. Thermoregulation helps these butterflies prepare for maximum flight efficiency in order to gain ownership of the most optimal territory.[5]

Displaying

Male graylings make short and frequent flights, both spontaneous and non-spontaneous. These may function as a signal of display for females.[5]

Pheromones

The male graylings’ courtship procedure for copulation may also serve to indicate to the female the amount and the nature of the males’ sex pheromones. Further research must be conducted to determine this for certain, but the courtship procedure likely plays a role in pheromone production. Hipparchia semele only copulate once, so determining the best possible male, based on the pheromones and courting procedure, is very important for reproductive success. Pheromone releasers are located all over the wings of the males.[9]

Mate choice

Grayling females partake in resource defense polygyny.[5] Females choose a territorial male in order to gain the best oviposition site.[5] This allows for a higher survival rate of the eggs, as well as the inheritance of the ability to defend the best territories which are attractive to females, leading to a higher reproductive rate of the offspring, thus allowing the female grayling a higher opportunity to propagate her genes.

_courting_female_(l)_male_(r)_Macedonia.jpg.webp)

Courting

A complex courtship procedure is performed by grayling males for copulation. The male moves behind the female, and engages in short movements around her until they are facing each other. Then, the male raises his forewings slowly, and quickly lowers and closes them, continuing this rhythmically. He then spreads his antennae to create a circular shape, and spreads his wings so the forewings are separated from the hindwings. After closing the wings again slowly, the male moves around the female again, and attempts copulation.[9]

Physiology

Flight

The grayling is a large and distinctive butterfly when in flight. The flight of a grayling is characterized by strong loops.[2]

The flying patterns of a grayling are also important in male-male interactions of territoriality. Initially, when defending a territory, each male grayling flies in a spiral motion, trying to be higher than and behind the other male. When this formation is stabilized, the two male graylings go into an alternating sequence of dives and climbs. At the end, the male that is able to achieve the highest position settles in the territory.[5]

Thermoregulation

The graylings prefer to live in open habitats, with easy access to the sun. This may be due to their ability to regulate their body temperature using the sun. When the temperature gets too cold, the grayling leans to expose its side towards the sunlight, therefore allowing its wings to gain heat from the sun. When the temperature gets too warm, the grayling stands straight, on its tiptoes, exposing its head towards the sun and keeping the majority of its body away.[2]

The male tends to orient its body and wings to control which parts of the body are exposed to the sun. This allows the grayling to keep its body temperature as close to the preferred level as possible. Therefore, at lower temperatures, the male grayling exposes as much of its body area as it can to increase the surface area facing the sun. This process is sometimes called sun-basking. This can raise body temperatures by up to 3 degrees Celsius. Contrarily, at high temperatures, the male grayling exposes as little of its body area as possible to the sun. This process can lower body temperatures by up to 2.5 degrees Celsius. At intermediate temperatures, the male grayling is often observed gradually changing his body orientation and posture in order to evenly spread the heat all over his body. This behavior can often be observed by male butterflies defending their territories.[5] Many times, the territories that male graylings defend are specific mating sites. Thermoregulation allows the male butterflies to maximize their efficiency, in order to prepare for optimal flight performance if another male enters the territory.[5]

Conservation (Great Britain)

The grayling has been decreasing in numbers significantly in recent years. While it was not considered of importance before, Hipparchia semele is now considered a priority species for conservation efforts in the United Kingdom.[10]

It is now a UK Biodiversity Action Plan species (Butterfly Conservation, 2007).

Habitat loss

Much of the Hipparchia semele’s common habitats, such as heathlands, have started to become transformed into agricultural land. The dry habitats are occupied by trees and other greenery, reducing the optimal available habitats for the graylings.[11]

References

- van Swaay, C.; Wynhoff, I.; Verovnik, R.; Wiemers, M.; López Munguira, M.; Maes, D.; Sasic, M.; Verstrael, T.; Warren, M.; Settele, J. (2010). "Hipparchia semele". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2010: e.T173254A6980554. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2010-1.RLTS.T173254A6980554.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- "Grayling" (PDF). Butterfly Conservation. February 2013. Retrieved October 2, 2017.

- Feltwell, John (1975). "Migration of the Hipparchia Semele" (PDF). Journal of Research on the Lepidoptera. 15: 83–91. doi:10.5962/p.333710. S2CID 248736523.

- Stevens, Martin (April 2005). "The role of eyespots as anti-predator mechanisms, principally demonstrated in the Lepidoptera" (PDF). Biological Reviews. 80 (4): 573–588. doi:10.1017/s1464793105006810. PMID 16221330. S2CID 24868603.

- Dreisig, H (15 December 1993). "Thermoregulation and flight activity in territorial male graylings, Hipparchiasemele (Satyridae), and large skippers, Ochlodesvenata (Hesperiidae)". Oecologia. 101 (2): 169–176. Bibcode:1995Oecol.101..169D. doi:10.1007/bf00317280. PMID 28306787. S2CID 22413242.

- Seitz, A. in Seitz. A. ed. Band 1: Abt. 1, Die Großschmetterlinge des palaearktischen Faunengebietes, Die palaearktischen Tagfalter, 1909, 379 Seiten, mit 89 kolorierten Tafeln (3470 Figuren)

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Stefanescu, Constantí; Traveset, Anna (2009). "Factors Influencing the Degree of Generalization in Flower Use by Mediterranean Butterflies". Oikos. 118 (7): 1109–1117. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.614.8751. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0706.2009.17274.x. JSTOR 40235422.

- Wiklund, Christer (1984). "Egg-laying patterns in butterflies in relation to their phenology and the visual apparency and abundance of their host plants". Oecologia. 63 (1): 23–29. Bibcode:1984Oecol..63...23W. doi:10.1007/bf00379780. PMID 28311161. S2CID 29210301.

- Pinzari, Manuela (November 2008). "A Comparative Analysis of Mating Recognition Signals in Graylings: Hipparchia statilinus vs. H. semele (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae, Satyrinae)". Journal of Insect Behavior. 22 (3): 227–244. doi:10.1007/s10905-008-9169-5. S2CID 30300261.

- "Grayling". UK Butterflies. Retrieved October 2, 2017.

- van Strein, Arco (July 2011). "Metapopulation dynamics in the grayling butterfly" (PDF). Bulletin of the Ecological Society of America. 92 (3): 290–291. doi:10.1890/0012-9623-92.3.290.

External links

- Butterfly Conservation website

- UK Butterflies website - includes a list of sites around the UK where this species can be found

Data related to Hipparchia semele at Wikispecies

Data related to Hipparchia semele at Wikispecies Media related to Hipparchia semele at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Hipparchia semele at Wikimedia Commons