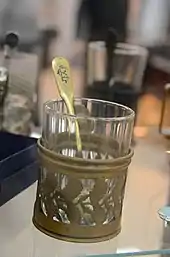

Faceted glass

A faceted glass or granyonyi stakan (Russian: гранёный стакан, literally faceted glass) (Ukrainian: granchak гранчак, derived from грань, meaning facet) is a type of drinkware made from especially hard and thick glass and having a faceted form. It is a very widespread form of drinking glass in Russia and the former Soviet Union.

Origins

The antecedents of the faceted glass in Russian history are dated back to the reign of Peter the Great, who valued the design as being less likely to roll off tables aboard ships.[1] Examples of the first such design were supposedly presented to the tsar by glassmaker Yefim Smolin, from Vladimir Governorate, with the assurance that the glass was unbreakable.[2] After drinking from the glass, the tsar threw it to the ground, breaking it, but was still impressed, stating "Let's have that glass" (Russian: Стакану быть!, romanized: Stakanu byit!). The breaking of the glass and the associated statement later became remembered as "break the glasses!" (Russian: Стаканы бить!, romanized: Stakany bit!) and is the possible origin of the Russian tradition of breaking glassware after celebrating particularly important toasts.[2]

.jpg.webp)

Glasses with different numbers of facets were produced in Tsarist Russia, with the museum collection in Vladimir-Suzdal including different types of faceted glass, some intended for drinking tea, others for drinking champagne.[3] The museum also holds examples of early 10-, 12-, 16-sided glasses.[3] The design appeared in still-life paintings by Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin, though the pre-Soviet designs were commonly cylindrical, with wider facets, and lacked the smooth rim of the later designs.[2]

The first Soviet glass tumbler to this design was produced at a glassware factory in Gus-Khrustalny District, either in Gus-Khrustalny or Urshelsky, with the date usually given as 11 September 1943.[4][3] The design is usually attributed to sculptor Vera Mukhina, who was in charge of the Leningrad Artistic Glass Workshop at this time.[4] Designed for use in Soviet canteens, the particular aspects of the design were necessitated by early Soviet dish washing machines, which restricted the size, shape and durability of the items they could process.[4][3] The design, which added a smooth ring at the top and a solid bottom, is sometimes called the "Mukhina" tumbler.[1] Annual production in the years following the Second World War reached between 500 million and 600 million glasses.[5] They were used in a wide variety of locations, from the Moscow Kremlin to prisons.[5]

The numbers of facets differed in Soviet designs, from 10 to 20, but the form was otherwise consistent, with the top of the glass formed by a smooth rim, conferring firmness.[4] The 16-sided design, a particularly common form, dates from the late 1940s–early 1950s.[3] The glass was made particularly thick, and sometimes tumblers were made from lead glass.[4] Though traditionally a very strong design, particular problems developed with those made in the 1980s, with cracking or separation of the glass bottom being among the flaws discovered. This was attributed to the use of foreign equipment in the production of the glasses.[4]

In Russian culture

The glasses became associated with the drinking of vodka during the anti-alcohol initiatives of the Khrushchev period, which limited the sale of vodka to 500-ml bottles. The standard Russian glasses would each hold a third of a bottle of vodka, and it became a tradition for drinkers to gather in threes to share a bottle split equally between each of their glasses.[4] From this came the popular Soviet expression "to arrange for three" Russian: сообразить на троих, romanized: soobraztit na troikh, and the continuing association of the type of glass with the drinking of vodka.[4] Drinking traditions associated with the design included the belief that viewing the world through the faceted glass made it appear better, and that vodka drunk from a faceted tumbler would never run out.[1]

More generally, the bevelled design of glass was ubiquitous in Soviet society, and was the standard form found in schools, hospitals, cafeterias, and other locations. They were used as convenient forms for standardised measures in cooking, with cookbooks often using numbers of glasses rather than grams or other measurements.[4][1] The standard glass size of 250 ml, when filled to the very top, was equivalent to cup under the imperial measurement system.[1][3][5] When filled up to the level of the smooth rim it contained 200 ml.[3] The glasses were also used as dough cutters for making pelmeni and vareniki, or for growing seedlings.[4]

With the advent of new and improved glassmaking techniques, the use of the Soviet-era design has declined in modern Russia. It remains popular however on Russian trains, usually alongside the use of podstakanniks for the serving of tea, and has become a symbol of the Russian railways.[4] The glass has been celebrated in commemorative events, such as that held in Izhevsk in 2005, where a 2.5 metres (8.2 ft) tower was created from 2,024 glass tumblers.[4] 11 September is now celebrated in Russia as "Faceted Glass Day".[2] One report on the design concluded that "it remains a piece of dishware that is always associated with Russia".[4] Viktor Yerofeyev noted that "In the archeology of Russian life, cleaning layer after layer, we will always return to the glass tumbler. This is our archeology, or rather, our matrix."[4]

See also

- Copo americano – Brazilian glassware

References

- Eremeeva, Jennifer (11 September 2014). "Glass Tumbler Day: A Venerable Soviet Icon". Retrieved 7 November 2019.

- "On the other side of the glass. History of faceted glass from Peter the Great to Petrov-Vodkin". mos.ru. 21 September 2019. Retrieved 7 November 2019.

- "Граненый стакан делают в Гусь-Хрустальном, а придумали в Америке" (in Russian). Komsomolskaya Pravda. 11 September 2013. Retrieved 7 November 2019.

- Yegorov, Oleg (10 September 2016). "Nothing humbler than the tumbler: 5 facts about the legendary Soviet glass". Russia Beyond. Retrieved 7 November 2019.

- "Design classic: the bevelled glass by Vera Mukhina". Financial Times. Retrieved 7 November 2019.