Good Roads Movement

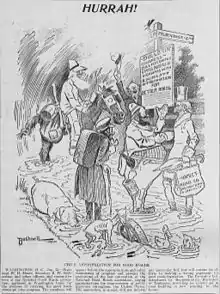

The Good Roads Movement occurred in the United States between the late 1870s and the 1920s. It was the rural dimension of the Progressive movement. A key player was the United States Post Office Department. Once a commitment was made for Rural Free Delivery of the mail, the Post Office had to determine which local roads were suitable and which were not. Farmers living on officially unusable roads now had motivation to get them upgraded.[1] Advocates for improved roads turned local agitation into a national political movement. It started as a coalition between farmers' organizations groups and bicyclists' organizations, such as the League of American Wheelmen. The goal was state and federal spending to improve rural roads. By 1910, automobile lobbies such as the American Automobile Association joined the campaign, coordinated by the National Good Roads Association.

Outside cities, roads were dirt or gravel; mud in the winter and dust in the summer. Travel was slow and expensive. Early organizers cited Europe where road construction and maintenance was supported by national and local governments. In its early years, the main goal of the movement was education for road building in rural areas between cities and to help rural populations gain the social and economic benefits enjoyed by cities where citizens benefited from railroads, trolleys and paved streets. Even more than traditional vehicles, the newly invented bicycles could benefit from good country roads.

History

The Good Roads Movement was officially founded in May 1880, when bicycle enthusiasts, riding clubs and manufacturers met in Newport, Rhode Island, to form the League of American Wheelmen to support the burgeoning use of bicycles and to protect their interests from legislative discrimination. The League quickly went national and in 1892 began publishing Good Roads magazine. In three years circulation reached one million. Early movement advocates enlisted the help of journalists, farmers, politicians and engineers in the project of improving the nation's roadways, but the movement took off when it was adopted by bicyclists.

Groups across the country held road conventions and public demonstrations, published material on the benefits of good roads and endeavoured to influence legislators on local, state and national levels. Support for candidates often became crucial factors in elections. Not only advocating road improvements for bicyclists, the League pressed the idea to farmers and rural communities, publishing literature such as the famous pamphlet, The Gospel of Good Roads.[2]

New Jersey became the first state to pass a law providing for a state to participate in road-building projects. In 1893, the U.S. Department of Agriculture initiated a systematic evaluation of existing highway systems. In that same year, Charles Duryea produced the first American gasoline-powered vehicle, and Rural Free Delivery began. By June 1894, "Many of the railway companies [had] made concessions in transporting road materials ranging from half rates to free carriage."[3]

20th century

At the turn of the twentieth century, interest in the bicycle began to wane in the face of increasing interest in automobiles. Subsequently, other groups took the lead in the road lobby. As the automobile was developed and gained momentum, organizations developed such cross-county projects as the coast-to-coast east–west Lincoln Highway in 1913, headed by auto parts and auto racing magnate Carl G. Fisher, and later his north–south Dixie Highway in 1915, which extended from Canada to Miami, Florida.

The movement gained national prominence when President Woodrow Wilson signed the Federal Aid Road Act of 1916 on July 11, 1916. In that year, the Buffalo Steam Roller Company of Buffalo, New York, and the Kelly-Springfield Company of Springfield, Ohio, merged to form the Buffalo-Springfield Company, which became the leader in the American compaction industry. Buffalo-Springfield enabled America to embark on a truly national highway construction campaign that continued into the 1920s.

Horatio Earle is known as the "Father of Good Roads". Quoting from Earle's 1929 autobiography: "I often hear now-a-days, the automobile instigated good roads; that the automobile is the parent of good roads. Well, the truth is, the bicycle is the father of the good roads movement in this country." "The League fought for the privilege of building bicycle paths along the side of public highways." "The League fought for equal privileges with horse-drawn vehicles. All these battles were won and the bicyclist was accorded equal rights with other users of highways and streets."

State Good Roads associations

The 1920 Directory of American Agricultural Organizations [4] lists the following state organizations as being affiliated with the Good Roads Movement:

- Alabama Good Roads Association

- Arizona Good Roads Association

- Central Florida Highway Association

- Good Roads Association of Wisconsin

- Illinois Association for Highway Improvement

- Kansas Good Roads Association

- Massachusetts Highway Association

- Michigan Pikes Association

- Michigan State Good Roads Association

- Montana Good Roads Congress

- Montana Highway Improvement Association

- Nebraska Good Roads Association

- Nevada Highway Association

- New Hampshire Good Roads Association

- New York Road Association

- North Carolina Good Roads Association

- Ohio Good Roads Federation

- Southeastern Idaho Good Roads Association

- Virginia Good Roads Association

- Washington State Good Roads Association

- Wilmington-Charlotte-Asheville Highway Association

- Wisconsin Highway Commissioners' Association

- Wyoming Good Roads Association

See also

References

- Wayne E. Fuller, "Good Roads and Rural Free Delivery of Mail< " Mississippi Valley Historical Review (1955) 42#1 pp 67-83. online

- The Gospel of Good Roads

- The Good Roads Crusade Cayuga Chief - Jun 2, 1894

- Directory of American Agricultural Organizations

Further reading

Scholarly studies

- Finkelstein, Alexander. "Colorado Honor Convicts: Roads, Reform, and Region in the Progressive Era". Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era 20.1 (2021): 24–43.

- Fuller, Wayne E. "Good roads and rural free delivery of mail". Mississippi Valley Historical Review 42.1 (1955): 67-83.

- Hugill, Peter J. "Good roads and the automobile in the United States 1880-1929". Geographical Review (1982): 327-349 online.

- Ingram, Tammy. Dixie Highway: Road Building and the Making of the Modern South, 1900-1930 (2013). It linked Chicago to Florida and helped modernize the South.

- Lee, Jason. "An Economic Analysis of the Good Roads Movement" (Institute of Transportation Studies, U of California, Davis; 2012) online

- Lichtenstein, Alex. "Good roads and chain gangs in the progressive South: 'the negro convict is a slave.' " Journal of Southern History (1993). 59#1: 85–110. online

- Longhurst, James. Bike battles: A history of sharing the American road (U of Washington Press, 2015).

- Mayo, Earl (July 1901). "The Good Roads Train". The World's Work. New York: Doubleday, Page & Co. II (3): 956–960. Retrieved April 29, 2012.

- Olliff, Martin T. Getting Out of the Mud: The Alabama Good Roads Movement and Highway Administration, 1898–1928 (U of Alabama Press, 2017). online review

- Reid, Carlton (2015). Roads Were Not Built for Cars. Washington: Island Press. ISBN 978-1-61091-689-9.

- Wells, Christopher W. (Spring 2006). "The Changing Nature of Country Roads: Farmers, Reformers, and the Shifting Uses of Rural Space, 1880-1905". Agricultural History. 80 (2): 143–166. doi:10.1525/ah.2006.80.2.143.

Advocacy in Good Roads magazine c. 1890–1920

- "Jan-Jun". I (old). 1892.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Jul-Dec". II (old). 1892.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Jan-Jun". III (old). 1892.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Jul-Dec". IV (old). 1893.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Jul-Dec". VI (old). 1893.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Jul-Dec". XXIV (old). 1896.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Jan-Jun". XXV (old). 1897.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Jul-Dec". XXVI (old). 1897.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Jan-Jun". XXVII (old). 1898.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Jan-Jul". XXIX (old). 1899.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Aug-Dec". XXX (old). 1899.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Jun-Dec". XXXI (old). 1900.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Jun-Dec". I (new). 1901.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Jan-Dec". II (new). 1903.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Jan-Dec". V (new). 1904.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Jan-Dec". VI (new). 1905.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Jan-Dec". VII (new). 1906.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Jan-Dec". VIII (new). 1907.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Jan-Dec". IX (new). 1908.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Jan-Dec". X (new). 1909.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Jan-Dec". XII (new). 1916.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Jan-Dec". XIV (new). 1917.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Jan-Jun". XV (new). 1918.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Jul-Dec". XVI (new). 1918.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Jul-Dec". LXI (new). 1921.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)

Advocacy in popular national periodicals c. 1880–1920 (examples)

- "Good Common Roads and How to Make Them". Outing. Boston MA: The Wheelman Company. V (3): 194–200. December 1884.

- Morrison, A. Cressy (April 1898). "The League of American Wheelmen". Frank Leslie's Popular Monthly. New York NY: Frank Leslie's Publishing House. XLV (4): 363–372.

- Cowles, Julia D. (June 1903). "The Good Roads Convention at St. Louis". The World To-Day. Chicago IL: Current Encyclopedia Company. IV (6): 761–771.

- Matthews, Franklin (June 1904). "Getting Good Roads in America". Outing. New York NY: The Outing Publishing Company. XLIV (3): 337–348.

- Burchell, H.P. (August 1905). "The Automobile as a means of Country Travel". Outing. New York NY: The Outing Publishing Company. XLVI (5): 536–541.

- Walsh, Thomas F. (January 1908). "Public highways and Prosperity". The National Magazine. Boston MA: The Chapple Publishing Company. XXVII (4).

- Page, Logan Waller (July 1909). "Good Roads the Way to Progress". The World's Work. New York, NY: Doubleday, Page & Company. XVIII (3): 11807–11819.

- Logan, Thomas F. (March 4, 1911). "Hastening the Millennium: How the Builders of Good Roads Hope to Turn American into Arcady". The Saturday Evening Post. 183 (36): 26–29.

- Page, Logan Waller (October 1912). "The Profit of Good Roads". The World's Work. Chicago, IL: Doubleday, Page & Company. XXIV (6): 695–679.

- Pennybacker Jr., J. E. (October 1912). "The Best Roads at Least Cost". The World's Work. Chicago, IL: Doubleday, Page & Company. XXIV (6): 679–687.

- Hewes, L. I. (October 1912). "Roads Worth $35,000,000 A Year". The World's Work. Chicago, IL: Doubleday, Page & Company. XXIV (6): 688–698.

- Joy, Henry B. (February 1914). "Transcontinental Trails: Their Development and What They Mean to this Country". Scribner's Magazine. New York NY: Charles Scribner's Sons. LV (2): 160–172.

- "The Economic and Social Value of Good Highways". Dun's Review. New York NY: R. G. Dun & Company. XXVIII (6): 42–45. August 1917.

- Goodell, John M. (February 1919). "An Apostle of Good Roads, Logan Waller Page". The American Review of Reviews. New York NY: The Review of Reviews Company. LVIX (2): 302–304.

Advocacy in books and pamphlets c. 1880–1920 (examples)

- Stone, Roy (1904). New Roads and Road Laws in the United States. New York NY: D. Van Nostrand Company. pp. 166.

- Davis, Charles Henry; Bates, Stanley Edwards (1913). National Highways to Bring About Good Roads Everywhere. Washington DC: National Highways Association. p. 46.

External links

- The Great Bicycle Protest of 1896

- Oklahoma Historical Society - Good Roads Association

- Weingroff, Richard F. (April 7, 2011). "A Maximum of Good Results: Martin Dodge and the Good Roads Train". Highway History. Federal Highway Administration.