Arabic numerals

The ten Arabic numerals 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9 are the most commonly used symbols for writing numbers. The term often also implies a positional notation using the numerals, as well as the use of a decimal base, in particular when contrasted with other systems such as Roman numerals. However, the symbols are also used to write numbers in other bases such as octal, as well as for writing non-numerical information such as trademarks or license plates identifiers.

| Part of a series on |

| Numeral systems |

|---|

| List of numeral systems |

They are also called Western Arabic numerals, Ghubār numerals, Hindu-Arabic numerals,[1] Western digits, Latin digits, or European digits.[2] The Oxford English Dictionary differentiates them with the fully capitalized Arabic Numerals to refer to the Eastern digits.[3] The term numbers or numerals or digits often implies only these symbols, however this can only be inferred from context.

Europeans learned of Arabic numerals about the 10th century, though their spread was a gradual process. Two centuries later, in the Algerian city of Béjaïa, the Italian scholar Fibonacci first encountered the numerals; his work was crucial in making them known throughout Europe. European trade, books, and colonialism helped popularize the adoption of Arabic numerals around the world. The numerals have found worldwide use significantly beyond the contemporary spread of the Latin alphabet, and have become common in the writing systems where other numeral systems existed previously, such as Chinese and Japanese numerals.

History

Origin

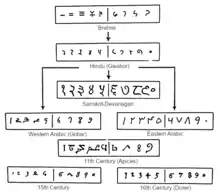

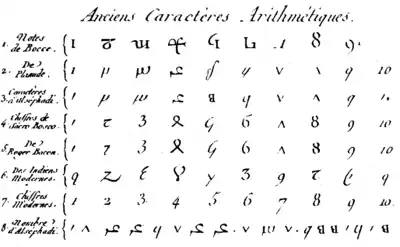

Positional decimal notation including a zero symbol was developed in India, using symbols visually distinct from those that would eventually enter into international use. As the concept spread, the sets of symbols used in different regions diverged over time.

The immediate ancestors of the digits now commonly called "Arabic numerals" were introduced to Europe in the 10th century by Arabic speakers of Spain and North Africa, with digits at the time in wide use from Libya to Morocco. In the eastern part of the Arabian Peninsula, the Arabs were using the Eastern Arabic numerals or "Mashriki" numerals: ٠, ١, ٢, ٣, ٤, ٥, ٦, ٧, ٨, ٩.[4]

Al-Nasawi wrote in the early 11th century that mathematicians had not agreed on the form of the numerals, but most of them had agreed to train themselves with the forms now known as Eastern Arabic numerals.[5] The oldest specimens of the written numerals available are from Egypt and date to 873–874 AD. They show three forms of the numeral "2" and two forms of the numeral "3", and these variations indicate the divergence between what later became known as the Eastern Arabic numerals and the Western Arabic numerals.[6] The Western Arabic numerals came to be used in the Maghreb and Al-Andalus from the 10th century onward.[7] Some amount of consistency in the Western Arabic numeral forms endured from the 10th century, found in a Latin manuscript of Isidore of Seville's Etymologiae from 976 and the Gerbertian abacus, into the 12th and 13th centuries, in early manuscripts of translations from the city of Toledo.[4]

Calculations were originally performed using a dust board (takht, Latin: tabula), which involved writing symbols with a stylus and erasing them. The use of the dust board appears to have introduced a divergence in terminology as well: whereas the Hindu reckoning was called ḥisāb al-hindī in the east, it was called ḥisāb al-ghubār in the west (literally, "calculation with dust").[8] The numerals themselves were referred to in the west as ashkāl al‐ghubār ("dust figures") or qalam al-ghubår ("dust letters").[9] Al-Uqlidisi later invented a system of calculations with ink and paper "without board and erasing" (bi-ghayr takht wa-lā maḥw bal bi-dawāt wa-qirṭās).[10]

A popular myth claims that the symbols were designed to indicate their numeric value through the number of angles they contained, but there is no contemporary evidence of this, and the myth is difficult to reconcile with any digits past 4.[11]

Adoption and spread

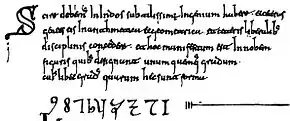

The first mentions of the numerals from 1 to 9 in the West are found in the 976 Codex Vigilanus, an illuminated collection of various historical documents covering a period from antiquity to the 10th century in Hispania.[12] Other texts show that numbers from 1 to 9 were occasionally supplemented by a placeholder known as sipos, represented as a circle or wheel, reminiscent of the eventual symbol for zero. The Arabic term for zero is sifr (صفر), transliterated into Latin as cifra, and the origin of the English word cipher.

From the 980s, Gerbert of Aurillac (later Pope Sylvester II) used his position to spread knowledge of the numerals in Europe. Gerbert studied in Barcelona in his youth. He was known to have requested mathematical treatises concerning the astrolabe from Lupitus of Barcelona after he had returned to France.[12]

The reception of Arabic numerals in the West was gradual and lukewarm, as other numeral systems circulated in addition to the older Roman numbers. As a discipline, the first to adopt Arabic numerals as part of their own writings were astronomers and astrologists, evidenced from manuscripts surviving from mid-12th-century Bavaria. Reinher of Paderborn (1140–1190) used the numerals in his calendrical tables to calculate the dates of Easter more easily in his text Compotus emendatus.[13]

Italy

Leonardo Fibonacci was a Pisan mathematician who had studied in Bugia, Algeria, and he endeavored to promote the numeral system in Europe with his 1202 book Liber Abaci:

When my father, who had been appointed by his country as public notary in the customs at Bugia acting for the Pisan merchants going there, was in charge, he summoned me to him while I was still a child, and having an eye to usefulness and future convenience, desired me to stay there and receive instruction in the school of accounting. There, when I had been introduced to the art of the Indians' nine symbols through remarkable teaching, knowledge of the art very soon pleased me above all else and I came to understand it.

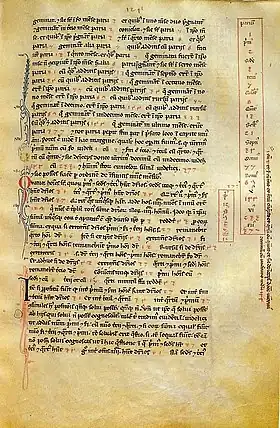

The Liber Abaci introduced the huge advantages of a positional numeric system, and was widely influential. As Fibonacci used the symbols from Béjaïa for the digits, these symbols were also introduced in the same instruction, ultimately leading to their widespread adoption.[14]

Fibonacci's introduction coincided with Europe's commercial revolution of the 12th and 13th centuries, centered in Italy. Positional notation could be used for quicker and more complex mathematical operations (such as currency conversion) than Roman and other numeric systems could. They could also handle larger numbers, did not require a separate reckoning tool, and allowed the user to check a calculation without repeating the entire procedure.[14] Although positional notation opened possibilities that were hampered by previous systems, late medieval Italian merchants did not stop using Roman numerals (or other reckoning tools). Rather, Arabic numerals became an additional tool that could be used alongside others.[14]

Europe

By the late 14th century, only a few texts using Arabic numerals appeared outside of Italy. This suggests that the use of Arabic numerals in commercial practice, and the significant advantage they conferred, remained a virtual Italian monopoly until the late 15th century.[14] This may in part have been due to language barriers: although Fibonacci's Liber Abaci was written in Latin, the Italian abacus traditions was predominantly written in Italian vernaculars that circulated in the private collections of abacus schools or individuals. It was likely difficult for non-Italian merchant bankers to access comprehensive information.

The European acceptance of the numerals was accelerated by the invention of the printing press, and they became widely known during the 15th century. Their use grew steadily in other centers of finance and trade such as Lyon.[15] Early evidence of their use in Britain includes: an equal hour horary quadrant from 1396,[16] in England, a 1445 inscription on the tower of Heathfield Church, Sussex; a 1448 inscription on a wooden lych-gate of Bray Church, Berkshire; and a 1487 inscription on the belfry door at Piddletrenthide church, Dorset; and in Scotland a 1470 inscription on the tomb of the first Earl of Huntly in Elgin Cathedral.[17] In central Europe, the King of Hungary Ladislaus the Posthumous, started the use of Arabic numerals, which appear for the first time in a royal document of 1456.[18]

By the mid-16th century, they were in common use in most of Europe. Roman numerals remained in use mostly for the notation of Anno Domini (“A.D.”) years, and for numbers on clock faces. Other digits (such as Eastern Arabic) were virtually unknown.

Russia

Prior to the introduction of Arabic numerals, Cyrillic numerals, derived from the Cyrillic alphabet, were used by South and East Slavs. The system was used in Russia as late as the early 18th century, although it was formally replaced in official use by Peter the Great in 1699.[19] Reasons for Peter's switch from the alphanumerical system are believed to go beyond a surface-level desire to imitate the West. Historian Peter Brown makes arguments for sociological, militaristic, and pedagogical reasons for the change. At a broad, societal level, Russian merchants, soldiers, and officials increasingly came into contact with counterparts from the West and became familiar with the communal use of Arabic numerals. Peter also covertly travelled throughout Northern Europe from 1697 to 1698 during his Grand Embassy and was likely informally exposed to Western mathematics during this time.[20] The Cyrillic system was found to be inferior for calculating practical kinematic values, such as the trajectories and parabolic flight patterns of artillery. With its use, it was difficult to keep pace with Arabic numerals in the growing field of ballistics, whereas Western mathematicians such as John Napier had been publishing on the topic since 1614.[21]

China

While positional Chinese numeral systems such as the counting rod system and Suzhou numerals had been in use prior to the introduction of Arabic numerals,[22][23] the externally-developed system was eventually introduced to medieval China by the Hui people. In the early 17th century, European-style Arabic numerals were introduced by Spanish and Portuguese Jesuits.[24][25][26]

Encoding

The ten Arabic numerals are encoded in virtually every character set designed for electric, radio, and digital communication, such as Morse code. They are encoded in ASCII (and therefore in Unicode encodings[27]) at positions 0x30 to 0x39. Masking all but the four least-significant binary digits gives the value of the decimal digit, a design decision facilitating the digitization of text onto early computers. EBCDIC used a different offset, but also possessed the aforementioned masking property.

| ASCII Binary | ASCII Octal | ASCII Decimal | ASCII Hex | Unicode | EBCDIC Hex | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0011 0000 | 060 | 48 | 30 | U+0030 DIGIT ZERO | F0 |

| 1 | 0011 0001 | 061 | 49 | 31 | U+0031 DIGIT ONE | F1 |

| 2 | 0011 0010 | 062 | 50 | 32 | U+0032 DIGIT TWO | F2 |

| 3 | 0011 0011 | 063 | 51 | 33 | U+0033 DIGIT THREE | F3 |

| 4 | 0011 0100 | 064 | 52 | 34 | U+0034 DIGIT FOUR | F4 |

| 5 | 0011 0101 | 065 | 53 | 35 | U+0035 DIGIT FIVE | F5 |

| 6 | 0011 0110 | 066 | 54 | 36 | U+0036 DIGIT SIX | F6 |

| 7 | 0011 0111 | 067 | 55 | 37 | U+0037 DIGIT SEVEN | F7 |

| 8 | 0011 1000 | 070 | 56 | 38 | U+0038 DIGIT EIGHT | F8 |

| 9 | 0011 1001 | 071 | 57 | 39 | U+0039 DIGIT NINE | F9 |

Comparison with other digits

See also

Citations

- "Arabic numeral". American Heritage Dictionary. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. 2020. Archived from the original on 21 November 2021. Retrieved 21 November 2021.

- Terminology for Digits Archived 26 October 2021 at the Wayback Machine. Unicode Consortium.

- "Arabic", Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd edition

- Burnett, Charles (2002). Dold-Samplonius, Yvonne; Van Dalen, Benno; Dauben, Joseph; Folkerts, Menso (eds.). From China to Paris: 2000 Years Transmission of Mathematical Ideas. Franz Steiner Verlag. pp. 237–288. ISBN 978-3-515-08223-5. Archived from the original on 30 July 2022. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- Kunitzsch 2003, p. 7: "Les personnes qui se sont occupées de la science du calcul n'ont pas été d'accord sur une partie des formes de ces neuf signes; mais la plupart d'entre elles sont convenues de les former comme il suit."

- Kunitzsch 2003, p. 5.

- Kunitzsch 2003, pp. 12–13: "While specimens of Western Arabic numerals from the early period—the tenth to thirteenth centuries—are still not available, we know at least that Hindu reckoning (called ḥisāb al-ghubār) was known in the West from the 10th century onward..."

- Kunitzsch 2003, p. 8.

- Kunitzsch 2003, p. 10.

- Kunitzsch 2003, pp. 7–8.

- Ifrah, Georges (1998). The universal history of numbers: from prehistory to the invention of the computer. Translated by David Bellos (from the French). London: Harvill Press. pp. 356–357. ISBN 9781860463242.

- Nothaft, C. Philipp E. (3 May 2020). "Medieval Europe's satanic ciphers: on the genesis of a modern myth". British Journal for the History of Mathematics. 35 (2): 107–136. doi:10.1080/26375451.2020.1726050. ISSN 2637-5451. S2CID 213113566.

- Herold, Werner (2005). "Der "computus emendatus" des Reinher von Paderborn". ixtheo.de (in German). Archived from the original on 30 July 2022. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- Danna, Raffaele (12 July 2021). The Spread of Hindu-Arabic Numerals in the European Tradition of Practical Arithmetic: a Socio-Economic Perspective (13th–16th centuries) (Doctoral thesis). University of Cambridge. doi:10.17863/cam.72497. Archived from the original on 27 July 2021. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- Danna, Raffaele; Iori, Martina; Mina, Andrea (22 June 2022). "A Numerical Revolution: The Diffusion of Practical Mathematics and the Growth of Pre-modern European Economies". SSRN 4143442.

- "14th century timepiece unearthed in Qld farm shed". ABC News. Archived from the original on 29 February 2012. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- See G. F. Hill, The Development of Arabic Numerals in Europe, for more examples.

- Erdélyi: Magyar művelődéstörténet 1-2. kötet. Kolozsvár, 1913, 1918.

- Conatser Segura, Sylvia (26 May 2020). Orthographic Reform and Language Planning in Russian History (Honors thesis). Archived from the original on 30 July 2022. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- Brown, Peter B. (2012). "Muscovite Arithmetic in Seventeenth-Century Russian Civilization: Is It Not Time to Discard the "Backwardness" Label?". Russian History. 39 (4): 393–459. doi:10.1163/48763316-03904001. ISSN 0094-288X. Archived from the original on 30 July 2022. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- Lockwood, E. H. (October 1978). "Mathematical discoveries 1600-1750, by P. L. Griffiths. Pp 121. £2·75. 1977. ISBN 0 7223 1006 4 (Stockwell)". The Mathematical Gazette. 62 (421): 219. doi:10.2307/3616704. ISSN 0025-5572. JSTOR 3616704. Archived from the original on 30 July 2022. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- Shell-Gellasch, Amy (2015). Algebra in context : introductory algebra from origins to applications. J. B. Thoo. Baltimore. ISBN 978-1-4214-1728-8. OCLC 907657424.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Uy, Frederick L. (January 2003). "The Chinese Numeration System and Place Value". Teaching Children Mathematics. 9 (5): 243–247. doi:10.5951/tcm.9.5.0243. ISSN 1073-5836. Archived from the original on 30 July 2022. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- Helaine Selin, ed. (1997). Encyclopaedia of the history of science, technology, and medicine in non-western cultures. Springer. p. 198. ISBN 978-0-7923-4066-9. Archived from the original on 27 October 2015. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- Meuleman, Johan H. (2002). Islam in the era of globalization: Muslim attitudes towards modernity and identity. Psychology Press. p. 272. ISBN 978-0-7007-1691-3. Archived from the original on 27 October 2015. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- Peng Yoke Ho (2000). Li, Qi and Shu: An Introduction to Science and Civilization in China. Mineola, New York: Courier Dover Publications. p. 106. ISBN 978-0-486-41445-4. Archived from the original on 27 October 2015. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- "The Unicode Standard, Version 13.0" (PDF). unicode.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 June 2001. Retrieved 1 September 2021.

General and cited sources

- Kunitzsch, Paul (2003). "The Transmission of Hindu-Arabic Numerals Reconsidered". In J. P. Hogendijk; A. I. Sabra (eds.). The Enterprise of Science in Islam: New Perspectives. MIT Press. pp. 3–22. ISBN 978-0-262-19482-2.

Further reading

- Burnett, Charles (2006). "The Semantics of Indian Numerals in Arabic, Greek and Latin". Journal of Indian Philosophy. Springer-Netherlands. 34 (1–2): 15–30. doi:10.1007/s10781-005-8153-z. S2CID 170783929.

- Hayashi, Takao (1995). The Bakhshālī Manuscript: An Ancient Indian Mathematical Treatise. Groningen, Netherlands: Egbert Forsten. ISBN 906980087X.

- Ifrah, Georges (2000). A Universal History of Numbers: From Prehistory to Computers. New York: Wiley. ISBN 0471393401.

- Katz, Victor J., ed. (20 July 2007). The Mathematics of Egypt, Mesopotamia, China, India, and Islam: A Sourcebook. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691114859.

- "Mathematics in South Asia". Nature. 189 (4761): 273. 1961. Bibcode:1961Natur.189S.273.. doi:10.1038/189273c0. S2CID 4288165.

- Ore, Oystein (1988). "Hindu-Arabic numerals". Number Theory and Its History. Dover. pp. 19–24. ISBN 0486656209.

External links

- Lam Lay Yong, "Development of Hindu Arabic and Traditional Chinese Arithmetic", Chinese Science 13 (1996): 35–54.

- "Counting Systems and Numerals", Historyworld. Retrieved 11 December 2005.

- The Evolution of Numbers. 16 April 2005.

- O'Connor, J. J., and E. F. Robertson, Indian numerals Archived 6 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine. November 2000.

- History of the numerals