Far-right politics in Germany (1945–present)

The far-right in Germany (German: rechtsextrem) slowly reorganised itself after the fall of Nazi Germany and the dissolution of the Nazi Party in 1945. Denazification was carried out in Germany from 1945 to 1949 by the Allied forces of World War II, with an attempt of eliminating Nazism from the country. However, various far-right parties emerged in the post-war period, with varying success. Most parties only lasted a few years before either dissolving or being banned, and explicitly far-right parties have never gained seats in the Bundestag (Germany's federal parliament) post-WWII.

The closest was the hard-right Deutsche Rechtspartei (German Right Party), which attracted former Nazis and won five seats in the 1949 West German federal election and held these seats for four years, before losing them in the 1953 West German federal election.[1] The Homeland (formerly known as the National Democratic Party of Germany (NPD) until 2023), founded in 1964, is the only national neo-Nazi political party remaining in Germany.

Definition

"Far-right" is synonymous with the term "extreme right", or literally "right-extremist" (the term used by German Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution), according to which neo-Nazism is a subclass, with its historical orientation at Nazism.[2]

West Germany (1945–1990)

In 1946 the Deutsche Rechtspartei was founded and in 1950 succeeded by the Deutsche Reichspartei. As the allied occupation of Germany ended in 1949 a number of new far-right parties emerged: The Socialist Reich Party, founded in 1949, the German Social Union (West Germany), the Free German Workers' Party, Nationalist Front and National Offensive.

In 1964, the National Democratic Party of Germany was founded, which continues to the present day.

The 1980s saw an increase in right wing organization and activity across Western Europe. In 1984-5 the European Parliament organized a Committee of Inquiry into the Rise of Racism and Fascism in Europe, and in 1989 another Committee of Inquiry into Racism and Xenophobia. In the report of the second Committee, issued to parliament in October 1990, West German Social Democrat Willi Rothley argued that economic and social changes arising from "modernizing society" were responsible for the recent rise of right-wing extremism, particularly a weakening cohesion among family, work, and religious association leading to a "growing susceptibility to political platforms offering security by emphasizing the national aspect or providing scapegoats (foreigners)."[3][4]

The report notes the "meteoric" rise of the Republikaner Partei (REP) in 1989, whose leader Franz Schönhuber had been a member of the Waffen-SS, and who "proudly admits his Nazi past." The party won two million votes in the 1989 European Parliament elections on a platform that "openly advocated the abolition of trade unions, the destruction of social welfare, censorship, and the wholesale 'de-criminalization' of German history. Promoting the expulsion of immigrants and a reunification of Germany to the 1937 borders, the actual reunification of West and East Germany triggered a collapse of the REP's voter base. Until then, Helmut Kohl, as first chancellor of a reunified Germany, refused to guarantee Poland's western boundary. The German State Office for the Protection of the Constitution reported over 38,500 "extreme-rightists" in West Germany in 1989, but this number did not include 1-2 million members of the REP, while the NDP/DVU alliance, which was included, despite having only 27,000 members, won 455,000 votes in the June 1989 European elections. By 1991 a splinter group had formed into the Deutsche Allianz led by Harald Neubauer.After reunification, right-wing activity seems to have shifted primarily to the states of former East Germany, which included violent border incidents after the opening of visa-free travel between Germany and Poland in April 1991 [5]

Defunct parties

- Deutsche Rechtspartei (1946–1950)

- Socialist Reich Party (1949–1952) banned

- Deutsche Reichspartei (1950–1964)

- German Social Union (1956–1962)

- Free German Workers' Party (1979–1995)

- Nationalist Front (1985–1992) banned

- German Alternative (1989–1992) banned

- National Offensive (1990–1992) banned

East Germany (1945–1990)

East Germany (GDR) was founded under a different pretext than West Germany. As a socialist state, it was based on the idea that fascism was an extreme form of capitalism. Thus, it understood itself as an anti-fascist state (Article 6 of the GDR constitution) and anti-fascist and anti-colonialist education played an important role in schools and in ideological training at universities. In contrast to West Germany, organizations of the Nazi regime had always been condemned and their crimes openly discussed as part of the official state doctrine in the GDR. Thus, in the GDR, there was no room for a movement similar to the 1968 movement in West Germany, and GDR opposition groups did not see the topic as a major issue. Open right-wing radicalism was relatively weak until the 1980s. Later, smaller extremist groups formed (e.g. those associated with football violence). The government attempted to address the issue, but at the same time had ideological reasons not to do so openly as it conflicted with the self-image of a socialist society.[6][7]

Germany (since 1990)

In 1991, one year after German reunification, German neo-Nazis attacked accommodations for refugees and migrant workers in Hoyerswerda (Hoyerswerda riots), Schwedt, Eberswalde, Eisenhüttenstadt and Elsterwerda, and in 1992, xenophobic riots broke out in Rostock-Lichtenhagen. Neo-Nazis were involved in the murders of three Turkish girls in a 1992 arson attack in Mölln (Schleswig-Holstein), in which nine other people were injured.[8]

German statistics show that in 1991, there were 849 hate crimes, and in 1992 there were 1,485 concentrated in the eastern Bundesländer. After 1992, the numbers decreased, although they rose sharply in subsequent years. In four decades of the former East Germany, 17 people were murdered by far right groups.[9]

A 1993 arson attack by far-right skinheads on the house of a Turkish family in Solingen resulted in the deaths of two women and three girls, as well as in severe injuries for seven other people.[10] In the aftermath, anti-racist protests precipitated massive neo-Nazi counter-demonstrations and violent clashes between neo-Nazis and anti-fascists.

In 1995, the fiftieth anniversary of the Bombing of Dresden in World War II, a radical left group, the Anti-Germans (political current) started an annual rally praising the bombing on the grounds that so many of the city's civilians had supported Nazism.[11] Beginning in the late 1990s and early 2000s, Neo-Nazis started holding demonstrations on the same date. In 2009, the Junge Landsmannschaft Ostdeutschland youth group of the NPD organised a march but surrounded by policemen, the 6,000 neo-Nazis were not allowed to leave their meeting point. At the same time, some 15,000 people with white roses assembled in the streets holding hands to demonstrate against Nazism, and to create an alternative “memorial day” of war victims.[12]

In 2004, the National Democratic Party of Germany won 9.2% in the Saxony state election, 2004, and 1.6% of the nationwide vote in the German federal election, 2005. In the Mecklenburg-Vorpommern state election, 2006 the NPD received 7.3% of the vote and thus also state representation.[13] In 2004, the NPD had 5,300 registered party members.[14] Over the course of 2006, the NPD processed roughly 1,000 party applications which put the total membership at 7,000. The DVU has 8,500 members.[15]

In 2007, the Verfassungsschutz (Federal German intelligence) estimated the number of potentially right extremist individuals in Germany was 31,000 of which about 10,000 were classified as potentially violent (gewaltbereit).[16]

In 2008, unknown perpetrators smashed cars with Polish registrations and breaking windows in Löcknitz, a German town near the Polish city Szczecin, where about 200 Poles live. Supporters of the NPD party were suspected to be behind anti-Polish incidents, per Gazeta Wyborcza.[17]

In 2011, the National Socialist Underground was finally exposed in being behind the murders of 10 people of Turkish origins between 2000 and 2007.[18]

In 2011, Federal German intelligence reported 25,000 right-wing extremists, including 5,600 neo-Nazis.[19] In the same report, 15,905 crimes committed in 2010 were classified as far-right motivated, compared to 18,750 in 2009; these crimes included 762 acts of violence in 2010 compared to 891 in 2009.[19] While the overall numbers had declined, the Verfassungsschutz indicated that both the number of neo-Nazis and the potential for violent acts have increased, especially among the growing number of Autonome Nationalisten ("Independent Nationalists") who gradually replace the declining number of Nazi Skinheads.[19]

In the 2014 European Parliament election, the NPD won their first ever seat in the European Parliament with 1% of the vote.[20] Jamel, Germany is a village known to be heavily populated with neo-Nazis.[21]

According to interior ministry figures reported in May 2019, of an estimated 24,000 far-right extremists in the country, 12,700 Germans are inclined towards violence. Extremists belonging to Der Dritte Weg (the third way) marched through a town in Saxony on 1 May, the day before the Jewish remembrance of the Holocaust, carrying flags and a banner saying "Social justice instead of criminal foreigners".[22] In 2020, Deutsches Reichsbräu beer with neo-Nazi imagery was sold in Bad Bibra on Holocaust Memorial Day.[23]

In October 2019, the city council of Dresden passed a motion declaring a "Nazi emergency", signalling that there is a serious problem with the far right in the city.[24]

In February 2020, following an observation of a conspiratorial meeting of a dozen right-wing extremists, those involved were arrested after agreeing to launch attacks on mosques in Germany to trigger a civil war.[25][26]

The National Democratic Party (NPD) in Germany has made efforts to be incorporated into the environmental movement in an effort to attract new members amongst the younger generations. They have published conservation magazines including Umwelt und Aktiv (Environment and Active). This magazine and others of its kind incorporate both environmentalism and tips as well as far-right propaganda and rhetoric. It's argued by an anonymous member of the Centre for Democratic Culture that this endeavor is in part a rebranding of the NPD. They argue that the party is attempting to become associated with environmentalism and not politics.[27]

Support from the East

After 1990, far-right and German nationalist groups gained followers, particularly among young people frustrated by the high unemployment and the poor economic situation.[28] Der Spiegel also points out that these people are primarily single men and that there may also be socio-demographic reasons.[29] Since around 1998 the support for right-wing parties shifted from the south of Germany to the east.[30][31][32][33]

The far-right party German People's Union (DVU) formed in 1998 in Saxony-Anhalt and Brandenburg since 1999. In 2009, the party lost its representation in the Landtag of Brandenburg.[34]

The far-right National Democratic Party of Germany (NPD) was represented in the Saxon State Parliament from 2004 to 2014.[35][36] In Mecklenburg-Vorpommern the NPD losts its representation in the parliament following the 2016 state elections.[37] In 2009, Junge Landsmannschaft Ostdeutschland, supported by the NPD, organized a march on the anniversary of the Bombing of Dresden in World War II. There were 6,000 Nationalists which were met by tens of thousands of ″anti-Nazis″ and several thousand policemen.[38]

Pegida has its focus in eastern Germany.[39] A survey by TNS Emnid reports that in mid-December 2014, 53% of East Germans in each case sympathised with the PEGIDA demonstrators. (48% in the West)[40]

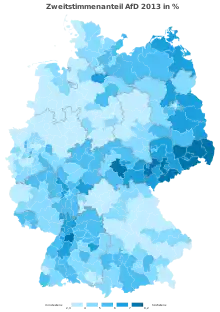

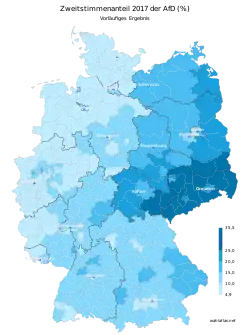

The Alternative for Germany (Alternative für Deutschland; AfD) had the most votes in the new states of Germany in the 2013 German federal elections, in 2017.[41] and in 2021 elections. The party is seen as harbouring anti-immigration views.[42]

In 2016, AfD reached at least 17% in Saxony-Anhalt,[43] Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania (where the NPD lost all seats)[44] and Berlin.[45]

In 2015, Rhineland-Palatinate interior minister Roger Lewentz said the former communist states were "more susceptible" to "xenophobic radicalization" because former East Germany had not had the same exposure to foreign people and cultures over the decades that the people in the West of the country have had.[46]

In the 2017 federal election, AfD received approximately 22% of the votes[47] in the East and approximately 11%[48] in the West.[49]

In the 2021 federal election, the AFD emerged as the largest in the states of Saxony and Thuringia, and saw a strong performance in eastern Germany.[50]

In 2018 Chemnitz, in the East German state of Saxony they had the 2018 Chemnitz protests anti immigration protests.

Legal issues

.svg.png.webp)

The German Criminal Code forbids the "use of symbols of unconstitutional organizations" outside the contexts of "art or science, research or teaching". However, Nazi paraphernalia has been smuggled into the country for decades.[51] Neo-Nazi rock bands such as Landser have been outlawed in Germany, yet bootleg copies of their albums printed in the United States and other countries are still sold in the country. German neo-Nazi websites mostly depend on Internet servers in the US and Canada. They often use symbols that are reminiscent of the swastika, and adopt other symbols used by the Nazis, such as the sun cross, wolf's hook and black sun.

Neo-Nazi groups active in Germany which have attracted government attention include Volkssozialistische Bewegung Deutschlands/Partei der Arbeit banned in 1982, Action Front of National Socialists/National Activists banned in 1983, the Nationalist Front banned in 1992, the Free German Workers' Party, the German Alternative and National Offensive. German Interior Minister Wolfgang Schäuble condemned the Homeland-Faithful German Youth, accusing it of teaching children that anti-immigrant racism and anti-Semitism are acceptable. Homeland-Faithful German Youth claimed that it was centred primarily on "environment, community and homeland", but it has been argued to have links to the National Democratic Party (NPD).[52]

Historian Walter Laqueur wrote in 1996 that the far right NPD cannot be classified as neo-Nazi.[53] In the 2004 Saxony state election, the NPD received 9.1% of the vote, thus earning the right to seat state parliament members.[54] The other parties refused to enter discussions with the NPD. In the 2006 parliamentary elections for Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, the NPD received 7.3% of the vote and six seats in the state parliament. On 13 March 2008, NPD leader Udo Voigt was charged with Volksverhetzung ("incitement to hatred", a crime under the German criminal law), for distributing racially charged pamphlets referring to German footballer Patrick Owomoyela, whose father is Nigerian. In 2009, Voigt was given a seven-month suspended sentence and ordered to donate 2,000 euros to UNICEF.[55]

See also

References

- Stone, Jon (24 September 2017). "German elections: Far-right wins MPs for first time in half a century". The Independent. Retrieved 15 February 2020.

- "What is right-wing extremism?". Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution. Archived from the original on 16 June 2018. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- Ford, Glyn (1992). Fascist Europe: The Rise of Racism and Xenophobia. London: Pluto Press. pp. xi–xii. ISBN 0-7453-0668-3.

- Ford, Glyn. "Fascist Europe: The Rise of Racism and Xenophobia" (PDF). Statewatch. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- Ford (1992), pp.xiv-xvii.

- Minkenberg, Michael (1994). "German unification and the continuity of discontinuities: Cultural change and the far right in east and west". German Politics. 3 (2): 169–192. doi:10.1080/09644009408404359.

- Rädel, Jonas (2019). "Two Paradigmatic Views on Right-Wing Populism in East Germany". German Politics and Society. 37 (4): 29–42. doi:10.3167/gps.2019.370404. S2CID 226813820.

- "Arson Attack in Mölln (November 28, 1992)". German History Institute. n.d. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- "Faschismus rund um den Bodensee" (in German). Archived from the original on 28 May 2004. Retrieved 27 March 2023.

- "Verfassungsschutz (Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution)". Verfassungsschutz-mv.de. Archived from the original on 16 March 2008. Retrieved 3 November 2009.

- James, Kyle (25 August 2006). "Strange Bedfellows: Radical Leftists for Bush". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 27 March 2023.

- Patrick Donahue (14 February 2009). "Skinheads, Neo-Nazis Draw Fury at Dresden 1945 'Mourning March'". Bloomberg. Retrieved 14 February 2009.

- "Poll boost for German far right". BBC News. 18 September 2006. Retrieved 27 March 2023.

- Jennifer L. Hochschild; John H. Mollenkopf (2009). Bringing Outsiders in: Transatlantic Perspectives on Immigrant Political Incorporation. Cornell University Press. p. 147. ISBN 978-0-8014-7514-6.

- "IRNA". Archived from the original on 9 February 2008.

- "Verfassungsschutzbericht 2007" (PDF). Bundesamt für Verfassungsschutz. Retrieved 27 March 2023.

- "Loecknitz nie chce Polaków" [Loecknitz doesn't want Poles]. Bankier.pl (in Polish). 17 January 2008. Retrieved 28 March 2023.

- "Germany probes suspected far-right murders". BBC News. 11 November 2011. Retrieved 28 March 2023.

- Fischer, Sebastian (1 July 2011). "Verfassungsschutz warnt vor getarnten Neonazis" [Office for the Protection of the Constitution warns against neo-Nazis in disguise]. Spiegel Online. Retrieved 1 July 2011.

- Adekoya, Remi; Smith, Helena; Davies, Lizzy; Penketh, Anne; Oltermann, Philip (26 May 2014). "Meet the new faces ready to sweep into the European parliament". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 January 2015.

- Popp, Maximilian (3 January 2011). "The Village Where the Neo-Nazis Rule". Der Spiegel. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- "Germany says half of extreme right 'prone to violence'". BBC News. 3 May 2019. Retrieved 4 May 2019.

- "German police probe Nazi-style beer brand". BBC News. 27 January 2020. Retrieved 2 July 2020.

- "Dresden: The German city that declared a 'Nazi emergency'". BBC News. 2 November 2019. Retrieved 2 November 2019.

- Schuetze, Christopher F. (14 February 2020). "Germany Says It's Broken Up a Far-Right Terrorism Network". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 16 February 2020.

- "German far-right 'terror cell' met on WhatsApp: report". Deutsche Welle. 16 February 2020. Retrieved 16 February 2020.

- Conolly, Kate (28 April 2012). "German Far-Right Extremists Tap into Green Movement for Support". The Guardian. Retrieved 28 March 2023.

- Boyes, Roger (20 August 2007). "Neo-Nazi rampage triggers alarm in Berlin". The Times. London. Archived from the original on 31 May 2010. Retrieved 11 October 2009.

- "Lack of Women in Eastern Germany Feeds Neo-Nazis". Spiegel International. 31 May 2007. Retrieved 11 October 2009.

- "Es war nicht immer der Osten – Wo Deutschland rechts wählt"./

- Pickel, Gert; Walz, Dieter; Brunner, Wolfram (9 March 2013). Deutschland nach den Wahlen: Befunde zur Bundestagswahl 1998 und zur Zukunft des deutschen Parteiensystems. Springer. ISBN 9783322933263.

- Steglich, Henrik (28 April 2010). Rechtsaußenparteien in Deutschland: Bedingungen ihres Erfolges und Scheiterns. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. ISBN 9783647369150.

- "Rechtsextremismus - ein ostdeutsches Phänomen?". www.bpb.de.

- "Landtagswahl Brandenburg 2009". Tagesschau. Archived from the original on 30 September 2009. Retrieved 22 October 2009.

- "Right-Wing Extremists Find Ballot-Box Success in Saxony". Spiegel International. 6 September 2008. Retrieved 26 November 2020.

- "Landtagswahl in Sachsen". Mitteldeutscher Rundfunk. Archived from the original on 12 October 2009. Retrieved 22 October 2009.

- "SPD gewinnt - AfD vor CDU - Grüne, FDP und NPD draußen". Der Spiegel. 5 September 2016. Retrieved 26 November 2020.

- Patrick Donahue. "Skinheads, Neo-Nazis Draw Fury at Dresden 1945 'Mourning March'". Bloomberg News. Retrieved 14 February 2009.

- "Pegida – "Ein überwiegend ostdeutsches Phänomen"" (in German). Retrieved 1 October 2016.

- Mehrheit der Ostdeutschen zeigt Verständnis. In: N24, 14 December 2014.

- Oltermann, Philip (28 September 2017). "'Revenge of the East'? How anger in the former GDR helped the AfD" – via www.theguardian.com.

- Troianovski, Anton (21 September 2017). "Anti-Immigrant AfD Party Draws In More Germans as Vote Nears". The Wall Street Journal.

- Statistisches Landesamt Sachsen-Anhalt: Wahl des 7. Landtages von Sachsen-Anhalt am 13. März 2016, Sachsen-Anhalt insgesamt Archived 2016-07-18 at the Wayback Machine

- "Wahl zum Landtag in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern 2016" (in German). Statistisches Amt MV: Die Landeswahlleiterin. 4 September 2016. Retrieved 14 September 2016.

- "tagesschau.de". wahl.tagesschau.de. Archived from the original on 18 September 2016. Retrieved 22 October 2017.

- "Eastern Germany 'more susceptible' to 'xenophobic radicalization' - News - DW - 31.08.2015". DW.COM.

- "Neue Bundesländer und Berlin-Ost Zweitstimmen-Ergebnisse". www.wahlen-in-deutschland.de.

- "Alte Bundesländer und Berlin-West Zweitstimmen-Ergebnisse". www.wahlen-in-deutschland.de.

- "Bundestagswahl 2017".

- "Germany's far-right populist AfD: No gains, small losses". Deutsche Welle. 27 September 2021. Retrieved 31 October 2021.

- "German Court Sentences U.S. Neo-Nazi". Los Angeles Times. Associated Press. 23 August 1996. Retrieved 29 July 2011.

- "Germany bans 'Nazi' Youth Group". BBC News. 31 March 2009. Retrieved 28 March 2023.

- Laqueur, Walter (1996). Fascism: Past, Present, Future. London and New York: Oxford University Press. p. 110. ISBN 0-19-509245-7.

- "Statistisches Landesamt des Freistaates Sachsen – Wahlen / Volksentscheide". Statistik.sachsen.de. Retrieved 3 November 2009.

- "Far-right politician convicted over racist World Cup flyers". Deutsche Welle. 24 April 2009. Retrieved 24 April 2009.

Further reading

- Ahmed, Reem; Pisoiu, Daniela (2021). "Uniting the far right: How the far-right extremist, New Right, and populist frames overlap on Twitter – a German case study" (PDF). European Societies. 23 (2): 232–254. doi:10.1080/14616696.2020.1818112. S2CID 225130483.

- Bitzan, Renate (2017). "Research on Gender and the Far Right in Germany Since 1990: Developments, Findings, and Future Prospects". Gender and Far Right Politics in Europe. pp. 65–78. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-43533-6_5. ISBN 978-3-319-43532-9.

- Bogerts, Lisa; Fielitz, Maik (2018). ""Do You Want Meme War?" Understanding the Visual Memes of the German Far Right" (PDF). Post-Digital Cultures of the Far Right. pp. 137–154. doi:10.1515/9783839446706-010. ISBN 9783839446706.

- Hardy, Keiran (2019). "Countering right-wing extremism: Lessons from Germany and Norway". Journal of Policing, Intelligence and Counter Terrorism. 14 (3): 262–279. doi:10.1080/18335330.2019.1662076. S2CID 211305922.

- Harvey, Elizabeth (2004). "Visions of the Volk : German Women and the Far Right from Kaiserreich to Third Reich". Journal of Women's History. 16 (3): 152–167. doi:10.1353/jowh.2004.0067. S2CID 143506094.

- Koehler, Daniel (2018). Right-Wing Terrorism in the 21st Century: The 'National Socialist Underground' and the History of Terror from the Far-Right in Germany. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781138542068.

- MacKlin, Graham (2013). "Transnational Networking on the Far Right: The Case of Britain and Germany". West European Politics. 36: 176–198. doi:10.1080/01402382.2013.742756. S2CID 144200666.

- Manthe, Barbara (2021). "On the Pathway to Violence: West German Right-Wing Terrorism in the 1970s". Terrorism and Political Violence. 33: 49–70. doi:10.1080/09546553.2018.1520701. S2CID 150252263.

- Miller-Idriss, Cynthia (2018). Extreme Gone Mainstream: Commercialization and Far Right Youth Culture in Germany. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691170206.

- Miller-Idriss, Cynthia (2017). "Soldier, sailor, rebel, rule-breaker: Masculinity and the body in the German far right". Gender and Education. 29 (2): 199–215. doi:10.1080/09540253.2016.1274381. S2CID 151886803.

- Rauchfleisch, Adrian; Kaiser, Jonas (2020). "The German Far-right on YouTube: An Analysis of User Overlap and User Comments". Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media. 64 (3): 373–396. doi:10.1080/08838151.2020.1799690. S2CID 221714793.

- Virchow, Fabian (2007). "Performance, Emotion, and Ideology: On the Creation of 'Collectives of Emotion' and Worldview in the Contemporary German Far Right". Journal of Contemporary Ethnography. 36 (2): 147–164. doi:10.1177/0891241606298822. S2CID 145059949.

External link

- "Germany's Neo-Nazis & the Far Right". Frontline. Season 39. Episode 21. 29 June 2021. PBS. WGBH. Retrieved 3 October 2023.