Geometrical frustration

In condensed matter physics, the term geometrical frustration (or in short: frustration[1]) refers to a phenomenon where atoms tend to stick to non-trivial positions or where, on a regular crystal lattice, conflicting inter-atomic forces (each one favoring rather simple, but different structures) lead to quite complex structures. As a consequence of the frustration in the geometry or in the forces, a plenitude of distinct ground states may result at zero temperature, and usual thermal ordering may be suppressed at higher temperatures. Much studied examples are amorphous materials, glasses, or dilute magnets.

The term frustration, in the context of magnetic systems, has been introduced by Gerard Toulouse in 1977.[2][3] Frustrated magnetic systems had been studied even before. Early work includes a study of the Ising model on a triangular lattice with nearest-neighbor spins coupled antiferromagnetically, by G. H. Wannier, published in 1950.[4] Related features occur in magnets with competing interactions, where both ferromagnetic as well as antiferromagnetic couplings between pairs of spins or magnetic moments are present, with the type of interaction depending on the separation distance of the spins. In that case commensurability, such as helical spin arrangements may result, as had been discussed originally, especially, by A. Yoshimori,[5] T. A. Kaplan,[6] R. J. Elliott,[7] and others, starting in 1959, to describe experimental findings on rare-earth metals. A renewed interest in such spin systems with frustrated or competing interactions arose about two decades later, beginning in the 1970s, in the context of spin glasses and spatially modulated magnetic superstructures. In spin glasses, frustration is augmented by stochastic disorder in the interactions, as may occur experimentally in non-stoichiometric magnetic alloys. Carefully analyzed spin models with frustration include the Sherrington–Kirkpatrick model,[8] describing spin glasses, and the ANNNI model,[9] describing commensurability magnetic superstructures. Recently, the concept of frustration has been used in brain network analysis to identify the non-trivial assemblage of neural connections and highlight the adjustable elements of the brain.[10]

Magnetic ordering

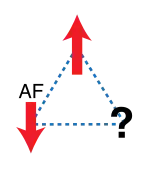

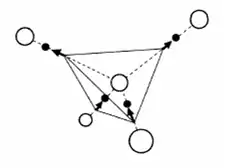

Geometrical frustration is an important feature in magnetism, where it stems from the relative arrangement of spins. A simple 2D example is shown in Figure 1. Three magnetic ions reside on the corners of a triangle with antiferromagnetic interactions between them; the energy is minimized when each spin is aligned opposite to neighbors. Once the first two spins align antiparallel, the third one is frustrated because its two possible orientations, up and down, give the same energy. The third spin cannot simultaneously minimize its interactions with both of the other two. Since this effect occurs for each spin, the ground state is sixfold degenerate. Only the two states where all spins are up or down have more energy.

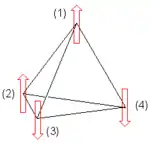

Similarly in three dimensions, four spins arranged in a tetrahedron (Figure 2) may experience geometric frustration. If there is an antiferromagnetic interaction between spins, then it is not possible to arrange the spins so that all interactions between spins are antiparallel. There are six nearest-neighbor interactions, four of which are antiparallel and thus favourable, but two of which (between 1 and 2, and between 3 and 4) are unfavourable. It is impossible to have all interactions favourable, and the system is frustrated.

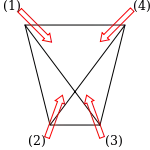

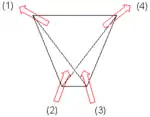

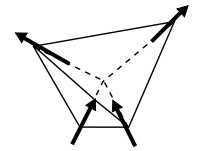

Geometrical frustration is also possible if the spins are arranged in a non-collinear way. If we consider a tetrahedron with a spin on each vertex pointing along the easy axis (that is, directly towards or away from the centre of the tetrahedron), then it is possible to arrange the four spins so that there is no net spin (Figure 3). This is exactly equivalent to having an antiferromagnetic interaction between each pair of spins, so in this case there is no geometrical frustration. With these axes, geometric frustration arises if there is a ferromagnetic interaction between neighbours, where energy is minimized by parallel spins. The best possible arrangement is shown in Figure 4, with two spins pointing towards the centre and two pointing away. The net magnetic moment points upwards, maximising ferromagnetic interactions in this direction, but left and right vectors cancel out (i.e. are antiferromagnetically aligned), as do forwards and backwards. There are three different equivalent arrangements with two spins out and two in, so the ground state is three-fold degenerate.

Mathematical definition

The mathematical definition is simple (and analogous to the so-called Wilson loop in quantum chromodynamics): One considers for example expressions ("total energies" or "Hamiltonians") of the form

where G is the graph considered, whereas the quantities Ikν,kμ are the so-called "exchange energies" between nearest-neighbours, which (in the energy units considered) assume the values ±1 (mathematically, this is a signed graph), while the Skν·Skμ are inner products of scalar or vectorial spins or pseudo-spins. If the graph G has quadratic or triangular faces P, the so-called "plaquette variables" PW, "loop-products" of the following kind, appear:

- and respectively,

which are also called "frustration products". One has to perform a sum over these products, summed over all plaquettes. The result for a single plaquette is either +1 or −1. In the last-mentioned case the plaquette is "geometrically frustrated".

It can be shown that the result has a simple gauge invariance: it does not change – nor do other measurable quantities, e.g. the "total energy" – even if locally the exchange integrals and the spins are simultaneously modified as follows:

Here the numbers εi and εk are arbitrary signs, i.e. +1 or −1, so that the modified structure may look totally random.

Water ice

Although most previous and current research on frustration focuses on spin systems, the phenomenon was first studied in ordinary ice. In 1936 Giauque and Stout published The Entropy of Water and the Third Law of Thermodynamics. Heat Capacity of Ice from 15 K to 273 K, reporting calorimeter measurements on water through the freezing and vaporization transitions up to the high temperature gas phase. The entropy was calculated by integrating the heat capacity and adding the latent heat contributions; the low temperature measurements were extrapolated to zero, using Debye's then recently derived formula.[11] The resulting entropy, S1 = 44.28 cal/(K·mol) = 185.3 J/(mol·K) was compared to the theoretical result from statistical mechanics of an ideal gas, S2 = 45.10 cal/(K·mol) = 188.7 J/(mol·K). The two values differ by S0 = 0.82 ± 0.05 cal/(K·mol) = 3.4 J/(mol·K). This result was then explained by Linus Pauling[12] to an excellent approximation, who showed that ice possesses a finite entropy (estimated as 0.81 cal/(K·mol) or 3.4 J/(mol·K)) at zero temperature due to the configurational disorder intrinsic to the protons in ice.

In the hexagonal or cubic ice phase the oxygen ions form a tetrahedral structure with an O–O bond length 2.76 Å (276 pm), while the O–H bond length measures only 0.96 Å (96 pm). Every oxygen (white) ion is surrounded by four hydrogen ions (black) and each hydrogen ion is surrounded by 2 oxygen ions, as shown in Figure 5. Maintaining the internal H2O molecule structure, the minimum energy position of a proton is not half-way between two adjacent oxygen ions. There are two equivalent positions a hydrogen may occupy on the line of the O–O bond, a far and a near position. Thus a rule leads to the frustration of positions of the proton for a ground state configuration: for each oxygen two of the neighboring protons must reside in the far position and two of them in the near position, so-called ‘ice rules’. Pauling proposed that the open tetrahedral structure of ice affords many equivalent states satisfying the ice rules.

Pauling went on to compute the configurational entropy in the following way: consider one mole of ice, consisting of N O2− and 2N protons. Each O–O bond has two positions for a proton, leading to 22N possible configurations. However, among the 16 possible configurations associated with each oxygen, only 6 are energetically favorable, maintaining the H2O molecule constraint. Then an upper bound of the numbers that the ground state can take is estimated as Ω < 22N(6/16)N. Correspondingly the configurational entropy S0 = kBln(Ω) = NkBln(3/2) = 0.81 cal/(K·mol) = 3.4 J/(mol·K) is in amazing agreement with the missing entropy measured by Giauque and Stout.

Although Pauling's calculation neglected both the global constraint on the number of protons and the local constraint arising from closed loops on the Wurtzite lattice, the estimate was subsequently shown to be of excellent accuracy.

Spin ice

A mathematically analogous situation to the degeneracy in water ice is found in the spin ices. A common spin ice structure is shown in Figure 6 in the cubic pyrochlore structure with one magnetic atom or ion residing on each of the four corners. Due to the strong crystal field in the material, each of the magnetic ions can be represented by an Ising ground state doublet with a large moment. This suggests a picture of Ising spins residing on the corner-sharing tetrahedral lattice with spins fixed along the local quantization axis, the <111> cubic axes, which coincide with the lines connecting each tetrahedral vertex to the center. Every tetrahedral cell must have two spins pointing in and two pointing out in order to minimize the energy. Currently the spin ice model has been approximately realized by real materials, most notably the rare earth pyrochlores Ho2Ti2O7, Dy2Ti2O7, and Ho2Sn2O7. These materials all show nonzero residual entropy at low temperature.

Extension of Pauling’s model: General frustration

The spin ice model is only one subdivision of frustrated systems. The word frustration was initially introduced to describe a system's inability to simultaneously minimize the competing interaction energy between its components. In general frustration is caused either by competing interactions due to site disorder (see also the Villain model[13]) or by lattice structure such as in the triangular, face-centered cubic (fcc), hexagonal-close-packed, tetrahedron, pyrochlore and kagome lattices with antiferromagnetic interaction. So frustration is divided into two categories: the first corresponds to the spin glass, which has both disorder in structure and frustration in spin; the second is the geometrical frustration with an ordered lattice structure and frustration of spin. The frustration of a spin glass is understood within the framework of the RKKY model, in which the interaction property, either ferromagnetic or anti-ferromagnetic, is dependent on the distance of the two magnetic ions. Due to the lattice disorder in the spin glass, one spin of interest and its nearest neighbors could be at different distances and have a different interaction property, which thus leads to different preferred alignment of the spin.

Artificial geometrically frustrated ferromagnets

With the help of lithography techniques, it is possible to fabricate sub-micrometer size magnetic islands whose geometric arrangement reproduces the frustration found in naturally occurring spin ice materials. Recently R. F. Wang et al. reported[14] the discovery of an artificial geometrically frustrated magnet composed of arrays of lithographically fabricated single-domain ferromagnetic islands. These islands are manually arranged to create a two-dimensional analog to spin ice. The magnetic moments of the ordered ‘spin’ islands were imaged with magnetic force microscopy (MFM) and then the local accommodation of frustration was thoroughly studied. In their previous work on a square lattice of frustrated magnets, they observed both ice-like short-range correlations and the absence of long-range correlations, just like in the spin ice at low temperature. These results solidify the uncharted ground on which the real physics of frustration can be visualized and modeled by these artificial geometrically frustrated magnets, and inspires further research activity.

These artificially frustrated ferromagnets can exhibit unique magnetic properties when studying their global response to an external field using Magneto-Optical Kerr Effect.[15] In particular, a non-monotonic angular dependence of the square lattice coercivity is found to be related to disorder in the artificial spin ice system.

Geometric frustration without lattice

Another type of geometrical frustration arises from the propagation of a local order. A main question that a condensed matter physicist faces is to explain the stability of a solid.

It is sometimes possible to establish some local rules, of chemical nature, which lead to low energy configurations and therefore govern structural and chemical order. This is not generally the case and often the local order defined by local interactions cannot propagate freely, leading to geometric frustration. A common feature of all these systems is that, even with simple local rules, they present a large set of, often complex, structural realizations. Geometric frustration plays a role in fields of condensed matter, ranging from clusters and amorphous solids to complex fluids.

The general method of approach to resolve these complications follows two steps. First, the constraint of perfect space-filling is relaxed by allowing for space curvature. An ideal, unfrustrated, structure is defined in this curved space. Then, specific distortions are applied to this ideal template in order to embed it into three dimensional Euclidean space. The final structure is a mixture of ordered regions, where the local order is similar to that of the template, and defects arising from the embedding. Among the possible defects, disclinations play an important role.

Simple two-dimensional examples

Two-dimensional examples are helpful in order to get some understanding about the origin of the competition between local rules and geometry in the large. Consider first an arrangement of identical discs (a model for a hypothetical two-dimensional metal) on a plane; we suppose that the interaction between discs is isotropic and locally tends to arrange the disks in the densest way as possible. The best arrangement for three disks is trivially an equilateral triangle with the disk centers located at the triangle vertices. The study of the long range structure can therefore be reduced to that of plane tilings with equilateral triangles. A well known solution is provided by the triangular tiling with a total compatibility between the local and global rules: the system is said to be "unfrustrated".

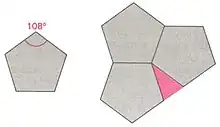

But now, the interaction energy is supposed to be at a minimum when atoms sit on the vertices of a regular pentagon. Trying to propagate in the long range a packing of these pentagons sharing edges (atomic bonds) and vertices (atoms) is impossible. This is due to the impossibility of tiling a plane with regular pentagons, simply because the pentagon vertex angle does not divide 2π. Three such pentagons can easily fit at a common vertex, but a gap remains between two edges. It is this kind of discrepancy which is called "geometric frustration". There is one way to overcome this difficulty. Let the surface to be tiled be free of any presupposed topology, and let us build the tiling with a strict application of the local interaction rule. In this simple example, we observe that the surface inherits the topology of a sphere and so receives a curvature. The final structure, here a pentagonal dodecahedron, allows for a perfect propagation of the pentagonal order. It is called an "ideal" (defect-free) model for the considered structure.

Dense structures and tetrahedral packings

The stability of metals is a longstanding question of solid state physics, which can only be understood in the quantum mechanical framework by properly taking into account the interaction between the positively charged ions and the valence and conduction electrons. It is nevertheless possible to use a very simplified picture of metallic bonding and only keeps an isotropic type of interactions, leading to structures which can be represented as densely packed spheres. And indeed the crystalline simple metal structures are often either close packed face-centered cubic (fcc) or hexagonal close packing (hcp) lattices. Up to some extent amorphous metals and quasicrystals can also be modeled by close packing of spheres. The local atomic order is well modeled by a close packing of tetrahedra, leading to an imperfect icosahedral order.

A regular tetrahedron is the densest configuration for the packing of four equal spheres. The dense random packing of hard spheres problem can thus be mapped on the tetrahedral packing problem. It is a practical exercise to try to pack table tennis balls in order to form only tetrahedral configurations. One starts with four balls arranged as a perfect tetrahedron, and try to add new spheres, while forming new tetrahedra. The next solution, with five balls, is trivially two tetrahedra sharing a common face; note that already with this solution, the fcc structure, which contains individual tetrahedral holes, does not show such a configuration (the tetrahedra share edges, not faces). With six balls, three regular tetrahedra are built, and the cluster is incompatible with all compact crystalline structures (fcc and hcp). Adding a seventh sphere gives a new cluster consisting in two "axial" balls touching each other and five others touching the latter two balls, the outer shape being an almost regular pentagonal bi-pyramid. However, we are facing now a real packing problem, analogous to the one encountered above with the pentagonal tiling in two dimensions. The dihedral angle of a tetrahedron is not commensurable with 2π; consequently, a hole remains between two faces of neighboring tetrahedra. As a consequence, a perfect tiling of the Euclidean space R3 is impossible with regular tetrahedra. The frustration has a topological character: it is impossible to fill Euclidean space with tetrahedra, even severely distorted, if we impose that a constant number of tetrahedra (here five) share a common edge.

The next step is crucial: the search for an unfrustrated structure by allowing for curvature in the space, in order for the local configurations to propagate identically and without defects throughout the whole space.

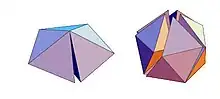

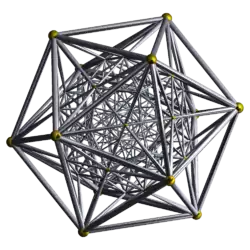

Regular packing of tetrahedra: the polytope {3,3,5}

Twenty irregular tetrahedra pack with a common vertex in such a way that the twelve outer vertices form a regular icosahedron. Indeed, the icosahedron edge length l is slightly longer than the circumsphere radius r (l ≈ 1.05r). There is a solution with regular tetrahedra if the space is not Euclidean, but spherical. It is the polytope {3,3,5}, using the Schläfli notation, also known as the 600-cell.

There are one hundred and twenty vertices which all belong to the hypersphere S3 with radius equal to the golden ratio (φ = 1 + √5/2) if the edges are of unit length. The six hundred cells are regular tetrahedra grouped by five around a common edge and by twenty around a common vertex. This structure is called a polytope (see Coxeter) which is the general name in higher dimension in the series containing polygons and polyhedra. Even if this structure is embedded in four dimensions, it has been considered as a three dimensional (curved) manifold. This point is conceptually important for the following reason. The ideal models that have been introduced in the curved Space are three dimensional curved templates. They look locally as three dimensional Euclidean models. So, the {3,3,5} polytope, which is a tiling by tetrahedra, provides a very dense atomic structure if atoms are located on its vertices. It is therefore naturally used as a template for amorphous metals, but one should not forget that it is at the price of successive idealizations.

Literature

- Sadoc, J. F.; Mosseri, R. (2007). Geometrical Frustration (reedited ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521031875.

- Sadoc, J. F., ed. (1990). Geometry in Condensed Matter Physics. Singapore: World Scientific. ISBN 9789810200893.

- Coxeter, H. S. M. (1973). Regular Polytopes. Dover Publishing. ISBN 9780486614809.

References

- The psychological side of this problem is treated in a different article, frustration

- Vannimenus, J.; Toulouse, G. (1977). "Theory of the frustration effect. II. Ising spins on a square lattice". J. Phys. C. 10 (18): L537. Bibcode:1977JPhC...10L.537V. doi:10.1088/0022-3719/10/18/008.

- Toulouse, Gérard (1980). "The frustration model". In Pekalski, Andrzej; Przystawa, Jerzy (eds.). Modern Trends in the Theory of Condensed Matter. Lecture Notes in Physics. Vol. 115. Springer Berlin / Heidelberg. pp. 195–203. Bibcode:1980LNP...115..195T. doi:10.1007/BFb0120136. ISBN 978-3-540-09752-5.

- Wannier, G. H. (1950). "Antiferromagnetism. The Triangular Ising Net". Phys. Rev. 79 (2): 357–364. Bibcode:1950PhRv...79..357W. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.79.357.

- Yoshimori, A. (1959). "A New Type of Antiferromagnetic Structure in the Rutile Type Crystal". J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 14 (6): 807–821. Bibcode:1959JPSJ...14..807Y. doi:10.1143/JPSJ.14.807.

- Kaplan, T. A. (1961). "Some Effects of Anisotropy on Spiral Spin-Configurations with Application to Rare-Earth Metals". Phys. Rev. 124 (2): 329–339. Bibcode:1961PhRv..124..329K. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.124.329.

- Elliott, R. J. (1961). "Phenomenological Discussion of Magnetic Ordering in the Heavy Rare-Earth Metals". Phys. Rev. 124 (2): 346–353. Bibcode:1961PhRv..124..346E. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.124.346.

- Sherrington, D.; Kirkpatrick, S. (1975). "Solvable Model of a Spin-Glass". Phys. Rev. Lett. 35 (26): 1792–1796. Bibcode:1975PhRvL..35.1792S. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.35.1792.

- Fisher, M. E.; Selke, W. (1980). "Infinitely Many Commensurate Phases in a Simple Ising Model". Phys. Rev. Lett. 44 (23): 1502–1505. Bibcode:1980PhRvL..44.1502F. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.44.1502.

- Saberi M, Khosrowabadi R, Khatibi A, Misic B, Jafari G (October 2022). "Pattern of frustration formation in the functional brain network". Network Neuroscience. 6 (4): 1334–1356. doi:10.1162/netn_a_00268.

- Debye, P. (1912). "Zur Theorie der spezifischen Wärmen" [On the theory of specific heats]. Ann. Phys. 344 (14): 789–839. Bibcode:1912AnP...344..789D. doi:10.1002/andp.19123441404.

- Pauling, Linus (1935). "The Structure and Entropy of Ice and of Other Crystals with Some Randomness of Atomic Arrangement". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 57 (12): 2680–2684. doi:10.1021/ja01315a102.

- Villain, J. (1977). "Spin glass with non-random interactions". J. Phys. C: Solid State Phys. 10 (10): 1717–1734. Bibcode:1977JPhC...10.1717V. doi:10.1088/0022-3719/10/10/014.

- Wang, R. F.; Nisoli, C.; Freitas, R. S.; Li, J.; McConville, W.; Cooley, B. J.; Lund, M. S.; Samarth, N.; Leighton, C.; Crespi, V. H.; Schiffer, P. (2006). "Artificial 'spin ice' in a geometrically frustrated lattice of nanoscale ferromagnetic islands" (PDF). Nature. 439 (7074): 303–6. arXiv:cond-mat/0601429. Bibcode:2006Natur.439..303W. doi:10.1038/nature04447. PMID 16421565. S2CID 1462022. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 23, 2017.

- Kohli, K. K.; Balk, Andrew L.; Li, Jie; Zhang, Sheng; Gilbert, Ian; Lammert, Paul E.; Crespi, Vincent H.; Schiffer, Peter; Samarth, Nitin (2011). "Magneto-optical Kerr effect studies of square artificial spin ice". Physical Review B. 84 (18): 180412. arXiv:1106.1394. Bibcode:2011PhRvB..84r0412K. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.84.180412. S2CID 119177920.