Geoffrey I of Villehardouin

Geoffrey I of Villehardouin (French: Geoffroi Ier de Villehardouin) (c. 1169 – c. 1229) was a French knight from the County of Champagne who joined the Fourth Crusade.[1][2][3][4] He participated in the conquest of the Peloponnese and became the second prince of Achaea (1209/1210–c. 1229).[2]

| Geoffrey I Geoffroi Ier | |

|---|---|

| Prince of Achaea | |

.jpg.webp) Seal of Geoffrey I | |

| Reign | 1209/1210–c. 1229 |

| Predecessor | William I |

| Successor | Geoffrey II |

| Born | c. 1169 Unknown |

| Died | c. 1229 Unknown |

| Burial | Church of St James, Andravida |

| Spouse | Elisabeth (of Chappes?) |

| Issue | Geoffrey II Alix William II |

| Dynasty | Villehardouin |

| Father | John of Villehardouin |

| Mother | Céline of Briel |

Under his reign, the Principality of Achaea became the direct vassal of the Latin Empire of Constantinople.[5] He extended the borders of his principality, but the closing years of his rule were marked by his conflict with the church.[6]

Early years and the Fourth Crusade

Geoffrey was the eldest son of John of Villehardouin and his wife, Céline of Briel.[2] He married one Elisabeth, traditionally identified with Elisabeth of Chappes,[7] a scion of a fellow crusader family, an identification rejected by Longnon.[8]

He took the cross with his uncle, Geoffrey of Villehardouin, the future chronicler of the Fourth Crusade, at a tournament of Écry-sur-Aisne in late November 1199.[3] Geoffrey were among the crusaders who went directly to Syria.[3] Thus he was not present at the occupation of Constantinople by the crusaders on 13 April 1204.[9]

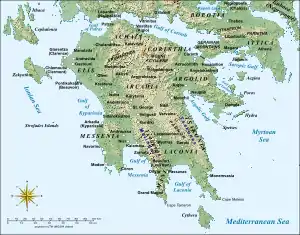

But hearing of the capture of the great city on the Bosporus, he decided to sail west in the summer of 1204.[3][10] But the weather became bad, and adverse winds drove him westward.[3] He landed at Modon (now Methoni, Greece) in the southern Peloponnese where he spent the winter of 1204–1205.[3][10]

Conquest of the Peloponnese

At Modon, Geoffrey entered into an alliance with a Greek archon (nobleman) from Messenia to conquer as much of the western Peloponnese as they could.[3][10] Almost immediately afterward, however, the Greek died, and his son broke off the alliance.[10] It was at this point that Geoffrey learned of the appearance of King Boniface I of Thessalonica (1204–1207) with his army before Nauplia (now Nafplion, Greece).[3] He determined to seek aid and rode up early in 1205 to join the king.[3][10] He was well received by Boniface I who would have retained Geoffrey in his service.[3] But in the camp at Nauplia, Geoffrey found his good friend William of Champlitte and offered to the latter to share the conquest of the Peloponnese.[3][11] His friend accepted the offer and the two also received royal permission for their expedition.[3]

They set out with 100 knights and 400 mounted men-at-arms upon their campaign in the spring of 1205.[12] They took Patras and Pondikos by assault, and Andravida opened its gates.[11] The people of the countryside came to make their submission and were confirmed in their property and local customs.[11] Only in Arcadia (now Kyparissia) were the crusaders resisted.[10] This opposition was led by landlords from Arcadia and Laconia, particularly the Chamaretos family, allied to the Slavic Melingoi tribe.[13] The resistance was soon joined by a certain Michael, identified by many scholars with Michael I Komnenos Doukas (1204–1215) who was then creating his own principality in Epiros.[14] Michael advanced into the Peloponnese with 5,000 men, but the little crusader army defeated him at Kountouras in northeast Messenia.[11][15] Then the crusaders completed the conquest of the region and advanced into the interior of the country, occupying the entire peninsula with the exception of Arcadia and Laconia.[11]

William of Champlitte thus became master of the Peloponnese with the title prince of Achaea (1205–1209) under the suzerainty of the king of Thessalonica.[11][15] Geoffrey received Kalamata and Messenia as a fief from the new prince.[15] However, the Republic of Venice proceeded to make good her claims that the leaders of the Fourth Crusade had guaranteed it by the partition treaty of 1204 to the important way stations along the sea route to Constantinople.[16][17] Thus the Venetians armed a fleet which took Modon and Coron (Koroni) in 1206,[16][17] but William of Champlitte compensated Geoffrey by assigning Arcadia to him.[17]

Reign in Achaea

In 1208 William I of Achaea departed for France in order to claim an inheritance his brother had left to him.[5][18] William I appointed Geoffrey to administer the principality as bailiff until the prince’s nephew, Hugh should arrive.[17] However, both the first prince of Achaea and his nephew died very shortly.[19]

In May 1209, Geoffrey went to the Parliament of Ravennika that the Latin Emperor Henry I (1206–1216) had convoked at Ravennika to assure the emperor of his loyalty.[5][20] The emperor confirmed Geoffrey as prince of Achaea and made him immediate imperial vassal.[5] Moreover, Henry I also appointed Geoffrey seneschal of the Latin Empire.[21]

The Chronicle of the Morea narrates that Geoffrey only became prince of Achaea some time later, because the late William I’s nephew, Robert had a year and a day to travel to the Peloponnese and claim his inheritance.[22] According to the story, all sorts of ruses were used to cause delays in Robert’s trip east, and when he finally arrived in the Peloponnese Geoffrey kept moving from place to place with the leading knights until the time had elapsed.[23] Geoffrey then held an assembly that declared that the heir had forfeited his rights and elected Geoffrey hereditary prince of Achaea.[23]

Nevertheless, already in June 1209 Geoffrey made a pact with the Venetians on the island of Sapientza, whereby he acknowledged himself to be the vassal of the Republic of Venice for all the lands extending from Corinth to the roadstead of Navarino (now Pylos, Greece).[5][21] Geoffrey I also gave Venice the right to free trade throughout his principality.[17]

Afterward Geoffrey I devoted himself to enlarging his possessions.[24] With the aid of Otto I, the lord of Athens (1204–1225), he seized, in 1209 or 1210, the fortress of Acrocorinth where first Leo Sgouros, and then Theodore Komnenos Doukas, brother of Michael I of Epirus had resisted the attacks of the crusaders.[20][24][25] In the months that followed, Nauplia was also taken, and early in 1212 the stronghold of Argos, where Theodore Komnenos Doukas had stored the treasure of the Church of Corinth, likewise fell into the hands of Geoffrey I and Otto I.[25] When Albertino and Rolandino of Canossa, the lords of Thebes had left their town, the lordship of Thebes was divided equally between Geoffrey I and the lord of Athens.[26]

Geoffrey I sent to France, mainly to Champagne, for young knights to occupy the newly conquered lands and the fiefs of those who had returned to the west.[24] Under Geoffrey I the assignment of fiefs and the obligations which went with them were reviewed before the barons assembled in a great parliament at Andravida.[27] Thus a dozen or so great baronies came into being in the principality, and those who received the titles to them made up with their many vassals the High Court of Achaea.[28]

At the time of the conquest much ecclesiastical property had been secularized and, despite the demands of the clergy, this had not been returned to the churches.[26] The Chronicle of the Morea reports that when the churches refused to provide their fair share of military aid, Geoffrey I seized their property and devoted the income from it to the construction of the powerful castle of Clermont.[26] Furthermore, Geoffrey I was also accused of treating the Greek priests as serfs because their numbers had considerably increased, since the Greek prelates showed no hesitation in conferring orders on peasants to permit them to escape the burdens of serfdom.[26] These events resulted in a prolonged conflict with the church.[26]

First the Latin Patriarch of Constantinople, Gervasius promulgated a decree of excommunication against Geoffrey I and laid an interdict upon Achaea.[29] Upon the request of Geoffrey I, however, on 11 February 1217 Pope Honorius III (1216–1227) declared that the patriarch was to relax the sentence within a week after the receipt of the papal letter.[29] Then the patriarch sent out a legate who laid a new interdict upon the Principality of Achaea.[30] But his act was again qualified by the pope as usurpation of the power of the Holy See.[30]

Next the papal legate Cardinal Giovanni Colonna who was travelling through the Peloponnese in 1218 excommunicated Geoffrey I because of the prince's contumacious retention of certain abbeys, churches, rural parishes, and ecclesiastical goods.[31] Upon the request of the local high clergy, the pope confirmed Geoffrey I's excommunication on 21 January 1219.[30] The pope even declared Geoffrey I to be an enemy of God “more inhuman than Pharaoh”.[26]

The conflict lasted some five years, until 1223 when Geoffrey I decided to negotiate and sent one of his knights to Rome.[26] Finally on September 4, 1223 Pope Honorius III confirmed the accord that had been drawn up between the prince and the church of Achaea.[26] According to the treaty, Geoffrey I restored the church lands, but he kept the treasures and furnishings of the churches in exchange for an annual indemnity and the number of Greek priests enjoying liberty and immunity was also to be limited in proportion to the size of the community.[26]

In the meantime, Theodore Komnenos Doukas, now ruler of Epirus (1215–1224), had attacked the kingdom of Thessalonica and laid siege the kingdom's capital.[4] William I, despite the urgent appeals of the pope, did not appear to have assisted the threatened city that finally surrendered near the end of 1224.[4][32]

Geoffrey died sometime between 1228 and 1230 at the age of about sixty.[4] He was buried in the Church of St James in Andravida.

Footnotes

- Runciman 1951, p. 126.

- Evergates 2007, p. 246.

- Setton 1976, p. 24.

- Longnon 1969, p. 242.

- Longnon 1969, p. 239.

- Longnon 1969, pp. 240-241.

- Evergates 2007, p. 263.

- Jean Longnon, Les compagnons de Villehardouin (1978), p. 36

- Setton 1976, pp. 12., 24.

- Fine 1994, p. 69.

- Longnon 1969, p. 237.

- Setton 1976, p. 25.

- Fine 1994, pp. 69-70.

- Fine 1994, pp. 70, 614.

- Fine 1994, p. 70.

- Longnon 1969, p. 238.

- Fine 1994, p. 71.

- Setton 1976, p. 33.

- Setton 1976, pp. 33-34.

- Fine 1994, p. 614.

- Setton 1976, p. 34.

- Fine 1994, pp. 71-72.

- Fine 1994, p. 72.

- Longnon 1969, p. 240.

- Setton 1976, p. 36.

- Longnon 1969, p. 241.

- Setton 1976, p. 30.

- Setton 1976, p. 31.

- Setton 1976, p. 46.

- Setton 1976, p. 47.

- Setton 1976, pp. 47-48.

- Setton 1976, p. 51.

References

- Bon, Antoine (1969). La Morée franque. Recherches historiques, topographiques et archéologiques sur la principauté d'Achaïe [The Frankish Morea. Historical, Topographic and Archaeological Studies on the Principality of Achaea] (in French). Paris: De Boccard. OCLC 869621129.

- Evergates, Theodore (2007). The Aristocracy in the County of Champagne, 1100-1300. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-4019-1.

- Fine, John V. A. Jr. (1994) [1987]. The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-08260-4.

- Longnon, Jean (1969) [1962]. "The Frankish States in Greece, 1204–1311". In Setton, Kenneth M.; Wolff, Robert Lee; Hazard, Harry W. (eds.). A History of the Crusades, Volume II: The Later Crusades, 1189–1311 (Second ed.). Madison, Milwaukee, and London: University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 234–275. ISBN 0-299-04844-6.

- Runciman, Steven (1954). A History of the Crusades, Volume III: The Kingdom of Acre and the Later Crusades. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Setton, Kenneth M. (1976). The Papacy and the Levant (1204–1571), Volume I: The Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries. Philadelphia: The American Philosophical Society. ISBN 0-87169-114-0.

Further reading

- Bratu, Cristian. “Clerc, Chevalier, Aucteur: The Authorial Personae of French Medieval Historians from the 12th to the 15th centuries.” In Authority and Gender in Medieval and Renaissance Chronicles. Juliana Dresvina and Nicholas Sparks, eds. (Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2012): 231-259.

- Finley Jr, John H. "Corinth in the Middle Ages." Speculum, Vol. 7, No. 4. (Oct., 1932), pp. 477–499.

- Tozer, H. F. "The Franks in the Peloponnese." The Journal of Hellenic Studies, Vol. 4. (1883), pp. 165–236.