Gennett Records

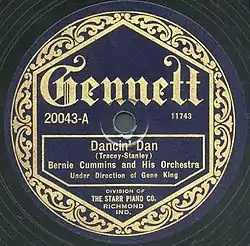

Gennett (pronounced "jennett") was an American record company and label in Richmond, Indiana, United States, which flourished in the 1920s. Gennett produced some of the earliest recordings by Louis Armstrong, King Oliver, Bix Beiderbecke, and Hoagy Carmichael. Its roster also included Jelly Roll Morton, Blind Lemon Jefferson, Charley Patton, and Gene Autry.

| Gennett Records | |

|---|---|

| |

| Founded | 1917 |

| Founder | Starr Piano Company |

| Defunct | 1947–48 |

| Status | Inactive |

| Genre | Jazz, blues, country |

| Country of origin | U.S. |

| Location | Richmond, Indiana, United States |

History

Gennett Records was founded in Richmond, Indiana, by the Starr Piano Company. It released its first records in October 1917. The company was named for its managers: Harry, Fred and Clarence Gennett.[1] The company had produced early recordings under the Starr Records label. The early issues were vertically cut in the phonograph record grooves, using the hill-and-dale method of a U-shaped groove and sapphire ball stylus, but they switched to the lateral cut method in April 1919.

Gennett set up recording studios in New York City and later, in 1921, set up a second studio on the grounds of the piano factory in Richmond under the supervision of Ezra C.A. Wickemeyer.

Gennett recorded early jazz musicians Jelly Roll Morton, Bix Beiderbecke, The New Orleans Rhythm Kings,[1] King Oliver's band with Louis Armstrong, Lois Deppe's Serenaders with Earl Hines,[2] Hoagy Carmichael, Duke Ellington, The Red Onion Jazz Babies, The State Street Ramblers, Zack Whyte and his Chocolate Beau Brummels, Alphonse Trent and his Orchestra and many others. Gennett also recorded early blues and gospel music artists such as Thomas A. Dorsey, Sam Collins, Jaybird Coleman, as well as early hillbilly or country music performers such as Vernon Dalhart, Bradley Kincaid, Ernest Stoneman, Fiddlin' Doc Roberts, and Gene Autry. Many early religious recordings were made by Homer Rodeheaver, early shape note singers and others.[3]

In the early 1920s, the studio was 125 feet (38 m) long and 30 feet (9.1 m) wide with a control room separated by a double pane of glass. For sound proofing, a Mohawk rug was placed on the floor and drapes and towels were hung on the wall.[4] Gennett issued a few early electrically recorded masters recorded in the Autograph studios in Chicago in 1925. These recordings were exceptionally crude, and like many other Autograph issues can be easily mistaken for acoustic masters. Gennett began serious electrical recording in March 1926, using a process licensed from General Electric which was found to be unsatisfactory. Although the quality of the recordings taken by the General Electric process was quite good, there were many customer complaints about poor wear characteristics of the electric process records. The composition of the Gennett biscuit (record material) was of insufficient hardness to withstand the increased wear that resulted when the new recordings with their greatly increased frequency range were played on obsolete phonographs with mica diaphragm reproducers. The company discontinued recording by this process in August 1926, and did not return to electric recording until February 1927, after signing a new agreement to license the RCA Photophone recording process. The company also introduced an improved record biscuit which was adequate to the demands imposed by the electric recording process. The improved records were identified by a newly designed black label touting the "New Electrobeam" process.

From 1925 to 1934, Gennett released recordings by hundreds of "old-time music" precursors to country music, including such artists as Doc Roberts and Gene Autry. By the late 1920s, Gennett was pressing records for more than 25 labels worldwide, including budget disks for the Sears catalog. In 1926, Fred Gennett created Champion Records as a budget label for tunes previously released on Gennett.[5]

The Gennett Company was hit severely by the Great Depression in 1930. It cut back on record recording and production until halting activities altogether in 1934. At this time, the only product Gennett Records produced under its own name was a series of recorded sound effects for use by radio stations. In 1935, the Starr Piano Company sold some Gennett masters, and the Gennett and Champion trademarks to Decca Records. Jack Kapp of Decca was primarily interested in jazz, blues and old time music items in the Gennett catalog which he thought would add depth to the selections offered by the newly organized Decca. Kapp attempted to revive the Gennett and Champion labels between 1935 and 1937 specializing in bargain pressings of race and old-time music with but little success.

The Starr record plant soldiered on under the supervision of Harry Gennett through the remainder of the decade by offering contract pressing services. For a time the Starr Piano Company was the principal manufacturer of Decca records, but much of this business dried up after Decca purchased its own pressing plant in 1938 (the Newaygo, Michigan, plant that formerly had pressed Brunswick and Vocalion records). In the years remaining before World War II, Gennett did contract pressing for New York-based jazz and folk music labels, including Joe Davis, Keynote and Asch.

With the coming of the Second World War, the War Production Board in March 1942 declared shellac a rationed commodity, limiting record manufacturers to 70% of their 1939 shellac usage. Newly organized record labels were forced to purchase their shellac from existing companies.[6] Joe Davis purchased the Gennett shellac allocation, some of which he used for his own labels, and some of which he sold to the newly formed Capitol Records. Harry Gennett intended to use the funds from the sale of his shellac ration to modernize this pressing plant after Victory, but there is no indication that he did so. Gennett sold decreasing numbers of special purpose records (mostly sound effects, skating rink, and church tower chimes) until 1947 or 1948, and the business then faded away.

Brunswick Records acquired the old Gennett pressing plant for Decca. After Decca opened a new pressing plant in Pinckneyville, Illinois, in 1956, the old Gennett plant in Richmond, Indiana, was sold to Mercury Records in 1958.[7] Mercury operated the historic plant until 1969 when it moved to a nearby modern plant later operated by Cinram.[8] Located at 1600 Rich Road, Cinram closed the plant in 2009.[9]

The Gennett company produced the Gennett, Starr, Champion, Superior, and Van Speaking labels, and also produced some Supertone, Silvertone, and Challenge records under contract. The firm pressed most Autograph, Rainbow, Hitch, Ku Klux Klan (KKK), Our Song, and Vaughn records under contract.

Gennett Walk of Fame

In September 2007, the Starr-Gennett Foundation began to honor the most important Gennett artists on a Walk of Fame near the site of Gennett's Richmond, Indiana, recording studio.

The Gennett Walk of Fame is located along South 1st Street in Richmond at the site of the Starr Piano Company and embedded in the Whitewater Gorge Trail, which connects to the longer Cardinal Greenway Trail. Both trails are part of the American Discovery Trail, the only coast-to-coast, non-motorized recreational trail.

The Foundation convened its National Advisory Board in January, 2006, to choose the first 10 inductees. The inductees are selected from: classic jazz, old-time country, blues, gospel (African-American and Southern), American popular song, ethnic, historic/spoken, and classical, giving preference to the first five categories.

The consensus selection for the first inductee in the Gennett Walk of Fame was Louis Armstrong.[10] The first ten inductees were:

- Louis Armstrong

- Bix Beiderbecke

- Jelly Roll Morton

- Hoagy Carmichael

- Gene Autry

- Vernon Dalhart

- Big Bill Broonzy

- Georgia Tom

- King Oliver

- Lawrence Welk

A second set of ten nominees was inducted in 2008:

- Homer Rodeheaver

- Fats Waller

- Duke Ellington

- Uncle Dave Macon

- Coleman Hawkins

- Charley Patton

- Sidney Bechet

- Blind Lemon Jefferson

- Fletcher Henderson

- Guy Lombardo

2009 Inductees:

- Artie Shaw

- Wendell Hall

- Bradley Kincaid

- Ernest Stoneman and Hattie Frost Stoneman

- New Orleans Rhythm Kings

2010 Inductees:

2011 Inductees:

- Roosevelt Sykes

- Bailey's Lucky Seven

2012 Inductees:

2013 Inductee:

2014 Inductee:

2016 Inductee:

References

- "Finding Aid for the Gennett Collection". Online Archive of California. Retrieved 19 October 2010.

- Tom Lord's The Jazz Discography says Hines' first recording was here with Deppe on 13 October 1923

- Mungons, Kevin and Douglas Yeo (2021). Homer Rodeheaver and the Rise of the Gospel Music Industry. Urbana, Illinos: University of Illinois Press. pp. 118, 176–77. ISBN 978-0-252-08583-3.

- Brothers, Thomas (2014). Louis Armstrong: Master of Modernism. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-393-06582-4.

- Kennedy, Rick (1994). Jelly Roll, Bix, and Hoagy: Gennett Studios and the Birth of Recorded Jazz. Indiana University Press. p. 141.

- Thomas, Bob (13 February 1971). "Patti Helps Re-Create War Years". The Portsmouth Times. Retrieved 30 October 2010.

- "Billboard". google.com. 5 May 1958. Retrieved 26 February 2015.

- "After the Starr Piano Company". StarrGennett.org. p. 6. Archived from the original on 23 July 2008.

- McGarvey, VJ (17 April 2009). "Letter to Indiana Department of Workforce Development" (PDF). IN.gov. Cinram. Retrieved 22 May 2015.

- "Gennett Records Walk of Fame". Starrgennett.org. 28 March 2014. Retrieved 23 March 2019.

External links

- The Starr-Gennett Foundation

- 2012 PBS History Detectives episode "Fiery Cross" regarding Klan records recorded at Gennett

- Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) No. IN-42, "Starr Piano Factory & Richmond Gas Company, G Street Bridge & Main Street Bridge, Richmond, Wayne County, IN", 6 photos, 6 data pages, 1 photo caption page

- Gennett Records on the Internet Archive's Great 78 Project

- Gennett Records discography at Discogs as 'Gennett'

- Gennett Records discography at Discogs as 'Gennett Records'