Gaddang people

The Gaddang (an indigenous Filipino people) are a linguistically-identified ethnic group resident in the watershed of the Cagayan River in Northern Luzon, Philippines. Gaddang speakers were recently reported to number as many as 30,000,[2] a number that may not include another 6,000 related Ga'dang speakers or other small linguistic-groups whose vocabularies are more than 75% identical.[3]

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 32,538[1] (2010) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

(Cagayan Valley, Cordillera Administrative Region) | |

| Languages | |

| Gaddang, Ga'dang, Yogad, Cauayeno, Arta, Ilocano, English, Tagalog | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity (Predominantly Roman Catholic, with a minority of Protestants) | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Ibanag, Itawis, Ilokano, other Filipino people |

| Demographics of the Philippines |

|---|

|

| Filipinos |

These proximate groups (speaking mutually-intelligible dialects which include Gaddang, Ga'dang, Baliwon,[4] Cauayeno, Majukayong, and Yogad, as well as historically-documented tongues such as that once spoken by the Irray of Tuguegarao) are depicted in cultural history and official literature today as a single people. Other distinctions are asserted between (a) Christian residents of the Isabela plains and Nueva Vizcaya valleys, and (b) formerly non-Christian residents in the nearby Cordillera mountains. Some reporters may exaggerate any of the differences, while others may completely ignore or gloss them over. The Gaddang have also in the past implemented a variety of social mechanisms that incorporate individuals born to linguistically-different peoples.

The Gaddang are indigenous to a compact geographic area; the theatre for their story is an area smaller than three-quarters of a million hectares (extreme distances: Bayombong to Ilagan=120 Km, Echague to Natonin=70 Km). The living population collectively comprises less than one-twentieth of one percent (.0005) of inhabitants of the Philippines, sharing one-quarter percent of the nation's land with Ifugao, Ilokano and others. As a people, Gaddang have no record of expansionism, they created no unique religion or set of beliefs, nor produced any notable government. The Gaddang identity is their language and their place.

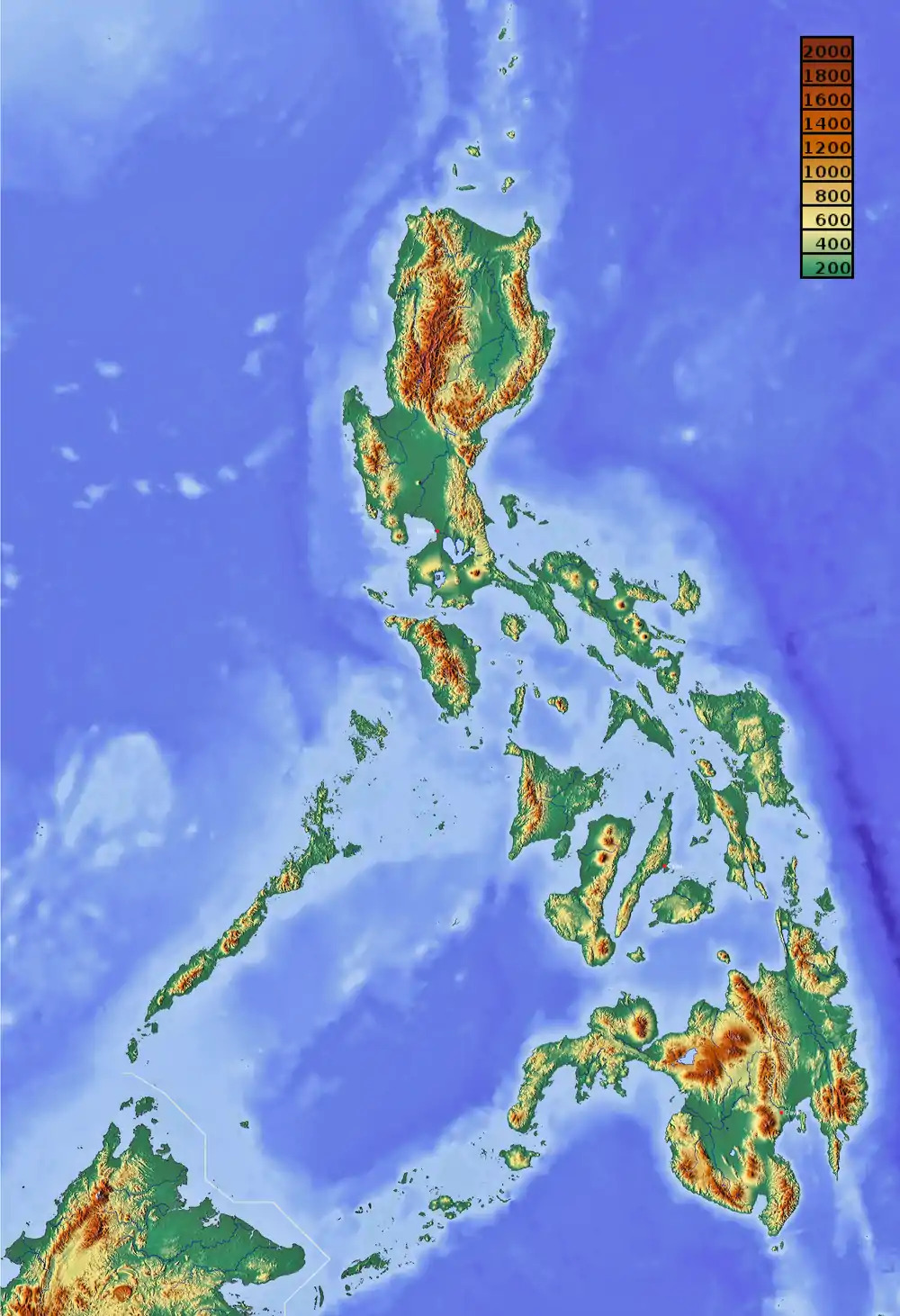

Physical geography

The Cagayan Valley (and its tributary watersheds Magat, Ilagan, the Mallig and Siffu of the Mallig Plains, and the Chico that enters the Cagayan just 30 miles from the sea) is cut-off from the rest of Luzon by mile-high forested mountain ranges joined at Balete Pass near Baguio. If one travels south from the mouth of the Cagayan River and along its largest tributary (the Magat[5]), the mountains become a dominant, brooding presence. The terraced Cordilleras close in from the west, the darker reaches of northern Sierra Madre arise in the east, meeting at the river sources in the Caraballo Mountains.

Once covered in continuous rainforest, today the valley-floor is a patchwork of intensive agriculture and mid-size civic centers surrounded by hamlets and small villages.[6] Even remote locations in the surrounding mountains now have permanent farm-establishments, all-weather roads, cell-phone towers, mines, and regular markets.[7] Often, native forest-flora has vanished, and any uncultivated areas sprout invasive cogon[8] or other weeds.

The International Fund for Agricultural Development in its 2012 study on Indigenous People's Issues in the Philippines identifies populations of Gaddang (including Baliwon, Majukayong, and iYogad) in Isabela, Nueva Ecija, Nueva Vizcaya, Quirino, and Mountain Provinces.[9]

A linguistic geography

The Cagayan Valley is physically divided from the rest of Luzon; Cagayan Valley cultures and languages are separated from other Luzon cultures and languages by social geography. The homelands of the Kapampangan (2.7 million speakers) and Pangasinan (1. 8 million) lie south of the mountains between the Cagayan and the enormous Tagalog-speaking population of Central Luzon – and are themselves barred from the valley by the diverse Igorot/Ilongot peoples of the Cordilleras and Caraballos. East of the valley, Kasigurinanin farmers and various "negrito" Aeta hunter-gatherers inhabit a few small communities in the Sierra and along the seashore. Through the 17th and 18th centuries, many Ilokano (now 8,000,000 worldwide) left their homes on the crowded northwest coast to labor on Cagayan Valley plantations; today's Ilokano-speakers in the Cagayan valley outnumber the original peoples several times over.[10] The Gaddang language has similarities to those of the Itawes and Malaueg settled at the more distant mouths of the Matalag and Chico rivers, as well as the more numerous Ibanag and Isneg of the valley.

Evidence[11] is that Gaddang occupied this vast protected valley jointly with culturally-similar neighbors for many hundred years.[12] Even among this half-million indigenes, however, the Gaddang are fewer than ten percent. Today's Gaddang identity has survived invasion, colonialism, suppression, assimilation, and nationalism.

Prior to use of a Filipino "national-language" or the official use of English dating from the early 1900s (even before the 1863 decree requiring Spanish in official life), 17th century Dominicans promulgated Ibanag as the sole medium for communication and education throughout the Valley. The Provincial Chapter of the Dominicans decreed in 1607: "Praecipientes ut omni studio et diligentia dent operam, ut linguam de Ibanag loquantur Yndi omnes, et in illa dictis indis ministrare studeant."[lower-alpha 1][13] In the area inhabited by Irraya-speakers (along the river from Tuguegaro to Ilagan[14]) this policy helped Ibanag to supersede the local languages. But most Gaddang language-variants (including Yogad and Cauayan) continued to remain vital and distinct from Ibanag,[15] a situation which persists in the southern Cagayan and Magat valleys and foothills of the Cordillera. Decades of linguistic studies document considerable identity among the Gaddangic tongues,[16] while revealing less intelligibility with Ibanag and Isneg.[17]

Evolving the idea of a people

Early depictions of Filipinos were written by conquerors to serve administrative, evangelical, or military purposes.[18] Writers ignored scientific rules of evidence, and may be unreliable about conditions.[19][20] There are no native reporters whose work survives. Consequently, descriptions from this period are an overlay imposed by foreign invaders on indigenous cultures.[21] As such, they promote the interests of church, crown, and the business of the local governing apparatus,[22] while failing to comprehend or accurately portray native concepts.

In 1902, the US Commissioner for Non-Christian Tribes wrote:

One impression that has gained a foothold in regard to tribes of the Philippines I believe to be erroneous, and that is as to the number of distinct types or races and multiplicity of tribes. Owing to the fact that nowhere in the Philippines do we encounter large political bodies or units, we have a superlative number of designations for what are practically identical people...For example, among the powerful and numerous Igorot of Northern Luzon, the sole political body is in the independent community. Under normal conditions, the town across the valley is an enemy and seeks the heads of its neighbors...Sometimes three or four different terms have been applied by different towns to identical peoples.[23]

So, there was no "Gaddang people" prior to the Spanish incursion; merely inhabitants of evanescent forest hamlets having tenuous relationships to people in similar settlements. Customs and language might be shared with neighbors, or they might not – the Spanish visitors created whole peoples from such tiny gatherings.[24] Nonetheless, we find the folk named long ago as Gaddang still residing in the same locales and using the same family names as were written down more than four hundred years ago.

At the end of the Spanish period, Fr. Julian Malumbres was writing his Historia de Nueva-Vizcaya y Provincia Montanõsa[25] (published after the American takeover), which carefully details the doings of the individual priests, administrators, and military persons throughout the several hundred years of the occupation. He is fairly vague about actions and customs of the native population.

American businessman Frederic H. Sawyer lived in Central Luzon beginning in 1886. He compiled The Inhabitants of the Philippines from official, religious, and mercantile sources during the last years of the Spanish administration. Published in 1900,[26] it was intended to be a resource for incoming Americans. His descriptions are meager and at best secondhand. In his section titled Gaddanes we recognize the pagan residents of the highlands. The residents of Bayombong, Bambang, Dupax, and Aritao, however, are called Italones, while their like in Isabela are the Irayas and the Catalanganes. These very terms are shown on military maps used by General Otis and his staff during the Philippine–American War.[27]

In 1917, respected University of the Philippines ethnologist/anthropologist H. Otley Beyer reported 21,240 Christian Gaddang ("civilized and enjoying complete self-government") and 12,480 Pagan Gaddang ("semi-sedentary agricultural groups enjoying partial self-government).[28] In this text, Beyer specifically notes that the Gaddang language "is divided into many dialects", and that all groups have a "marked intonation while speaking". He enumerated the Christian group as 16,240 Gaddang-speakers and 5,000 Yogad-speakers. Some Pagan Gaddang spoke Maddukayang/Majukayang (or Kalibungan) – a group totalling 8,480 souls. There were also 2,000 whose language was Katalangan[29] (an Aeta group farming the foothills of the Sierra Madre in San Mariano, described in 1860 by naturalist Carl Semper[30]), and another 2,000 speaking "Iraya."[31]).

A 1959 article by Fr. Godfrey Lambrecht, CICM is prefaced:

(The Gaddang) are the naturales of the towns of Bayombong, Solano, and Bagabag, towns built near the western bank of the Magat river (a tributary of...the Cagayan River) and of the towns of Santiago (Carig), Angadanan, Cauayan, and Reyna Mercedes... According to the census of 1939, the pagan Gadang numbered approximately 2,000, of whom some 1,400 lived in the outskirts of Kalinga and Bontok subprovinces... and some 600 were residing in the municipal districts of Antatet, Dalig , and the barrios of Gamu and Tumauini. Dalig is ordinarily said to be the place of origin of the Christianized Gadang. The same census records 14,964 Christians who spoke the Gadang language. Of these 6,790 were in Nueva Vizcaya, and 8,174 in Isabela. Among these, there were certainly some 3,000 to 4,000 who were not naturales but Ilocano, Ibanag, or Yogad who, because of infiltration, intermarriage, and daily contact with the Gadang, learned the language of the aborigines.[32]

The 1960 Philippine Census reported 6,086 Gaddang in the province of Isabela, 1,907 in what was then Mountain Province, and 5,299 in Nueva Vizcaya.[33] Using this data, Mary Christine Abriza wrote:

The Gaddang are found in northern Nueva Vizcaya, especially Bayombong, Solano, and Bagabag on the western bank of the Magat River, and Santiago, Angadanan, Cauayan, and Reina Mercedes on the Cagayan River for Christianed groups; and western Isabela, along the edges of Kalinga and Bontoc, in the towns of Antatet, Dalig, and the barrios of Gamu and Tumauini for the non-Christian communities. The 1960 census reports that there were 25,000 Gaddang and that 10% or about 2,500 of these were non-Christian.[34]

In April 2004, the National Statistics Office published a "Special Release"[35] outlining results of the 2000 Census of Population and Housing in the Philippines.[36] In those administrative regions with the largest concentrations of indigenous residents, Region II (10.5% of the nationwide indigenous population, Cagayan Valley IPS were 23.5% of all Region II residents), and the Cordillera Autonomous Region (CAR was home to 54.5% of all Philippine IPS, who comprised 11.9% of the CAR population). Gaddang and Yogad were among the 83 groups identified as IPs.

History

Material specifically relevant to the Gaddang (even when semi-distinct groups like Cauayeno and Yogad are included) over the past millennium is meagre. Important parts of the Gaddang story is lost today due to colonial suppression, ravages of armed conflict, careless or disinterested record-keeping and maintenance during inconstant administrations, and lack of documentary abilities and interest among the collective population. Extant historical data are largely concerned with specific places and events (property-records, parish vital statistics, &c.), or describe critical developments that affected large areas and populations. That said, such records do provide context and continuity for understanding the sporadic appearances of Gaddang peoples in the records.

Pre-history

Archeologists working in Peñablanca date the presence of humans in the Cagayan Valley as early as one-half million years ago.[37] Around 2000 B.C., Taiwanese nephrite (jade) was being worked along the north coast of Luzon and in the Batanes,[38] particularly at the Nagsabaran site in Claveria,[39] although this international industry had moved to Palawan by 500 CE.

Subsequent prehistory of Luzon is subject to significant disagreements on origins and timing; genetic studies were inconclusive as of 2021. Generally agreed, however, is that a series of colonizing parties of Austronesian peoples arrived from 200 B.C. to 300 A.D. along the northern coasts of Luzon,[40][12] where the river valleys were covered with a diverse flora and fauna.[41] They found the Cagayan River bottoms sparsely occupied by long-established Negrito Aeta/Arta peoples, while the hills had become home to more-recently arrived Cordilleran people (thought to originate directly from Taiwan as late as 500 B.C.[42]) and possibly the fierce, mysterious Ilongot in the Caraballos.

Unlike the Aeta hunter-gatherers or Cordilleran terrace-farmers, the Indo-Malay colonists of this period practiced swidden farming, and primitive littoral/riparian economies – collective communities that favor low population-density, frequent relocation, and limited social ties.[43] Without trade, the structure for such economies is rarely developed beyond the extended family group (according to Turner),[44] and may disappear beyond the limits of a single settlement. Such societies are typically suspicious of and hostile towards outsiders, and require members to relocate in the face of population pressure.[45]

The Indo-Malay arrived in separate small groups during this half-millennium,[40] undoubtedly speaking varying dialects; time and separation have indubitably promoted further linguistic fragmentation and realignment. Over generations they moved inland into valleys along the Cagayan River and its tributaries, pushing up into the foothills. The Gaddang occupy lands remote from the mouth of the river, so they are likely to have been among the earliest to arrive. All descendent-members of this 500-year-long migration, however, share elements of language, genetics, practices, and beliefs.[46] Ethnologists have recorded versions of a shared "epic" depicting describing the arrival of the heroes Biwag and Malana[47] (in some versions from Sumatra), their adventures with magic bukarot, and depictions of riverside life, among the Cagayan Valley populations including the Gaddang. Other cultural similarities include familial collectivism,[48][49] the dearth of endogamous practices,[50] and a marked indifference to, or failure to understand intergenerational conservation of assets.[51] These socially-flexible behaviors tend to foster immediate survival, but do relatively little to establish and maintain a strongly-differentiated continuity for each small group.

Cagayan Luzon Before Magellan

The undeveloped social organization in the Cagayan area was why the seafaring trade networks of Srivijaya and Majapahit established no permanent stations during their thousand years.[52] Neither were merchants of Tang and Song China attracted by undeveloped markets and the lack of industry in the area.[53] In the 14th century the short-lived and ineffective Mongol Yuan dynasty collapsed in a series of plagues, famines, and other disasters;[54] it led to the Ming policy of Haijin ("isolation"), and a substantial increase in Wokou piracy in the Luzon Straits. Unsettled conditions continued for several hundred years, putting a halt to any nascent international trade and immigration in the Cagayan watershed.[55] While Central Luzon and the southern islands enjoyed the results international commerce, the isolated Cagayan peoples were sequestered until the arrival of the militarily-advanced Spanish adventurers of the 1500s.

Arrival of the Spanish

The initial recorded census of Filipinos was conducted by the Spanish, based on tribute collection from Luzon to Mindanao in 1591 (26 years after Legazpi established the Spanish colonial administration); it found nearly 630,000 native individuals.[56][57][58][59] Prior to Legazpi, the islands had been visited by Magellan's 1521 expedition and the 1543 expedition of Villalobos. Using the reports of these expeditions, augmented by archeological data, scientific estimates of the Philippines population at the time of Legazpi's arrival run from slightly more than one million[60] to nearly 1.7 million.[61]

Even allowing for inefficiencies in early Spanish census methodology, data supports a claim that – over a mere quarter-century – military action and disease caused major population decline (40% or more) among the natives. Arrival of the Spanish (with their arms and diseases) was obviously a cataclysmic event. (Compare the dislocation modern roads and agricultural technology during the late 20th century brought to tiny highlands Gaddang communities[62]).

There is no doubt the Spanish occupation imposed an entirely incomprehensible social and economic order from that which had previously existed in the Cagayan valley. Missions and encomienda-ranching introduced concepts of land tenure sophisticated beyond the native's usufruct system of barely organized barangay communities farming temporary patches in the forest.[63] The indigenes saw church and crown demanding enormous tributes of labor and goods without any apparent recompense; the invaders considered natives to be property and their culture meaningless. Evanescent woodland hamlets and tiny, exclusive societies stood in the way of Spanish plans for economic exploitation – commercial agriculture in particular.[64] Trails through the forest were replaced by roads. Ranchos, towns, and missions sprang into existence New skills and social distinctions suddenly appeared, while old manners and folkways got forced into disuse within a single generation.

Colonization by Kastilya and the Church

In the Cagayan and nearby areas most immediately affecting the Gaddang, early expeditions led by Juan de Salcedo in 1572,[65] and Juan Pablo de Carrión (who drove-away Japanese pirates infesting the Cagayan coast)[66] initiated Spanish interest in the valley. Carrión established the alcalderia of Nueva Segovia in 1585. The natives immediately commenced what the Spanish considered anti-government revolts which flared up from the 1580s through the 1640s.[67] At least a dozen "rebellions" were documented in Northern and Central Luzon from the 1600s through the 1800s,[68][69][70] actions that indicate continuing antipathy between the occupiers and native populations.

Resistance notwithstanding, Spanish religious/military force established encomienda grants as far south as Tubigarao by 1591; in the same year Luis Pérez Dasmariñas (son of then-governor Gómez Pérez Dasmariñas) led an expedition north over the Caraballo mountains into what is now Nueva Vizcaya and Isabela.[71] In 1595-6 the Diocese of Nueva Segovia was decreed, and Dominican missionaries arrived.[72] The Catholic Church forcefully proselytized the Cagayan Valley from two directions, with Dominican missionaries continuing to open new missions southward in the name of Nueva Segovia (notably assisted by troops under the command of Capitan Fernando Berramontano),[73] while Augustinian friars pushing north from Pangasinan following the trail of the Dasmarinas expedition founded a mission near Ituy by 1609.[74] The seventeenth century began with the Gaddang in the sights of the Spanish advance for land and mineral wealth.[75]

The Gaddang entered written history in 1598 after the Dominicans managed to get permission from Guiab (a local headman)[76] to found their mission of San Pablo Apostol in Pilitan (now a barangay of Tumauini),[77] then the mission of St. Ferdinand in the Gaddang community of Abuatan, Bolo (now the rural barangay of Bangag, Ilagan City), in 1608 – thirty years (and thirty leagues) from the first Spanish settlements in the Cagayan region.[78] Missions sent south from Nueva Segovia continued to prosper and expand southward, eventually reaching the Diffun area (southern Isabela and Quirino) by 1702. Letters from the Dominican Provincial Jose Herrera to Ferdinand VI explicitly report that military activity was financed by, and considered an integral part of, the missions.[79]

Forced introduction of new crops and farming practices alienated the indigenes, as did collection of tithes, shares, and tribute. 1608 saw the assassination of Pilitan encomediero Luis Enriquez for his severe treatment of the Gaddang. In 1621, residents of Bolo led by Felipe Catabay and Gabriel Dayag commenced a Gaddang (or Irraya) Revolt[80] against the severe Church requisitions of labor and supplies, as Magalat had rebelled against Crown tribute at Tuguegarao a generation earlier.[81] Spanish religious and military records tell us that residents burned their villages and the church, then removed to the foothills west of the Mallig River (several days' journey). A generation later, Gaddang returnees — at the invitation of Fray Pedro De Santo Tomas — reestablished communities at Bolo and Maquila, though the location was changed to the opposite side of the Cagayan from the original village. Authorities claimed the Gaddang Revolt effectively over with the first mass held by the Augustinians on 12 April 1639 in Bayombong, Nueva Vizcaya, the so-called "final-stronghold" of the Gaddangs.

This protest/revolt created a distinction between the "Christianized" and "non-Christian" Gaddang.[82] Bolo-area Gaddang sought refuge with mountain tribes who had consistently refused to abandon traditional beliefs and practices for Catholicism. The Igorots of the Cordilleras killed Father Esteban Marin in 1601; subsequently, they waged a guerrilla resistance[83] after Captain Mateo de Aranada burned their villages. The mountaineers accepted the fleeing Gaddang as allies against the Spanish. Although the Gaddang refused to grow rice in terraces (preferring to continue their swidden economy), they learned to build tree-homes and hunt in the local style. Many Gaddang eventually returned to the valley, however, accepting Spain and the Church to follow the developing lowlands-farming lifestyle, taking advantage of material benefits not available to residents of the hills.

Heading north over the mountains, the Ituy mission initially baptized Isinay and Ilongot; thirty years later services were also being held for Gaddang in Bayombong. By the 1640s, though, that mission was defunct – the Magat valley was not operated with the comprehensive encomienda organization (and the military force that accompanied it) seen in the Nueva Segovia missions. The 1747 census, however, enumerates 470 native residents (meaning adult male Christians) in Bayombong and 213 from Bagabag, all said to be Gaddang or Yogad, in a re-established mission now called Paniqui.[84] With more than 680 households (3,000–4,500 people), the substantial size of these two Magat Valley Gaddang towns (100 kilometers from what is now Ilagan City) is an argument for more than a century's existence of a major native population in the area. By 1789, the Dominican Fr. Francisco Antolin made estimates of the Cordilleran population; his numbers of Gaddang in Paniqui are ten thousand, with another four thousand in the Cauayan region.[85]

The Gaddang are mentioned in Spanish records again in connection with the late-1700s rebellion of Dabo against the royal tobacco monopoly; it was suppressed in 1785 by forces dispatched from Ilagan by Governor Basco, equipped with firearms.[86] Ilagan City was by then the tobacco industry's financing and warehousing center for the Valley,[84] while the product was shipped from Aparri. Tobacco requires intense cultivation, and Cagayan natives were considered too few and too primitive to provide the needed labor. Workers from the western coastal provinces of Ilocos and Pangasinan were imported for the work. Today, descendants of those 18th and 19th-century immigrants (notably the Ilokano) outnumber by 7:1 descendants of the aboriginal Gaddang, Ibanag, and other Cagayan valley peoples.[87]

In the final century of Spain's rule of the islands saw the administration of the Philippines separated from that of Spain's American possessions, opening Manila to international trade, and the 1814 resumption of royal supremacy in government. Royal reform and re-organization of the Cagayan government and economy began with the creation of Nueva Vizcaya province in 1839. In 1865, Isabela province was created from parts of Cagayan and Nueva Vizcaya. The new administrations further opened Cagayan Valley lands to large-scale agricultural concerns funded by Spanish, Chinese, and wealthy Central Luzon investors, attracting more workers from all over Luzon.

But the initial business of these new provincial governments was dealing with head-hunting incursions that started in the early 1830s and continued into the early years of American rule. Tribesmen from Mayoyao, Silipan, and Kiangan ambushed travellers and even attacked towns from Ilagan to Bayombong, taking nearly 300 lives. More than 100 of the victims were Gaddang residents of Bagabag, Lumabang, and Bayombong. After Dominican Fr. Juan Rubio was decapitated on his way to Camarag, Governor Oscariz of Nueva Vizcaya led a force of more than 340 soldiers and armed civilians against the Mayoyao, burning crops and three of their villages. The Mayoyao sued for peace, and afterward, Oscariz led his troops through the hills as far as Angadanan.[71] By 1868, however, the governors of Lepanto, Bontoc, and Isabela provinces repeated the expedition through the Cordilleran highlands to suppress a new wave of headhunting.

During the Spanish period, education was entirely a function of the Church; its purpose was to convert indigenes to Catholicism. Although the throne decreed instruction was to be in Spanish, most friars found it easier to work in local tongues. This practice had the dual effect of maintaining local dialects/languages while suppressing Spanish literacy (minimizing the acquisition of individual social and political power, and suppressing national identity) among rural natives. The Education Decree of 1863 changed this, requiring primary education (and establishment of schools in each municipality) while requiring the use of Spanish language for instruction.[88] Implementation in remote areas of Northern Luzon, however, had not materially begun by the revolution of 1898.

Early in the Aguinaldo revolution, the main actions of the insurgents in the Cagayan Valley area were incursions by irregular Tagalog forces led by Major (later Colonel) Simeon Villa (Aguinaldo's personal physician, appointed the military commander of Katipunan troops in Isabela), Major Delfin, Colonel Leyba, and members of the family of Gov. Dismas Guzman[89] who were accused of robbery, torture, and killing of Spanish government functionaries, Catholic priests and their adherents,[90] for which several officers were later tried and convicted.[91] This characterization has been disputed by the American Justice James Henderson Blount, who served as U.S. District Judge in the Cagayan region 1901–1905.[92] Regardless of the truth of the accusations and counter-accusations we may be certain that in the area from Ilagan to Bayombong inhabited by Gaddang people violence by outsiders and local-officials for and against Spanish-government adherents inevitably affected the daily lives of those living in the area.

American occupation

The Philippines became a United States possession with the Treaty of Paris which ended the Spanish–American War in 1898.

The First Philippine Republic (primarily Manila-based illustrados and the principales who supported them) objected to the American claim to dispose of Philippine land-holdings throughout the islands, which voided grants made to Spain and the church by indigenes, but also eliminated communal ancestral holdings. What Filipino nationalists regarded as continuing their struggle for independence, the U.S. government considered as insurrection.[93] Aguinaldo's forces were driven out of Manila in February 1899 and retreated through Nueva Ecija, Tarlac, and eventually (in October) to Bayombong. After a month, though, Republic headquarters left Nueva Vizcaya on its final journey which would end in Palanan, Isabela, (captured by Philippine Scouts recruited from Pampanga) in March 1901. Gaddangs made few or none of the principales and none of the Manila oligarchy, but the action in Nueva Vizcaya and Isabela made them proximate to the agonies of the rebellion.

Perhaps the earliest official reference to the Gaddang during the American Occupation directs the reader to "Igorot".[94] The writers said of the "non-Christian" mountain tribes:

Under the Igorot, we may recognize various subgroup designations, such as Gaddang, Dadayag, or Mayoyao. These groups are not separated by tribal organization... since tribal organization does not exist among these people. but they are divided solely by slight differences of dialect.[95]

Among the practices of these Igorot peoples was headhunting. The Census also catalogues populations of the Cagayan lowlands, with theories about the origins of the inhabitants, saying:

Ilokano have also migrated still further south into the secluded valley of the upper Magat, which constitutes the beautiful but isolated province of Nueva Vizcaya. The bulk of the population here, however, differs very decidedly from nearly all of the Christian population of the rest of the Archipelago. It is made up of converts from two of the mountain Igorot tribes, who still have numerous pagan representative in this province and Isabela. These are the Isnay and Gaddang. In 1632 the Spaniard established a mission in this valley, named Ituy and led to the establishment of Aritao, Dupax, and Bambang, inhabited by the Christianized Isnay, and of Bayombong, Bagabag, and Ibung, inhabited by the Christianized Gaddang. The population, however, has not greatly multiplied, the remainder of the Christianized population being made up of Ilocano immigrants.[96]

The problematic but influential D. C. Worcester arrived in the Philippines as a zoology student in 1887, he was subsequently the only member of both the Schurman Commission and the Taft Commission. He travelled extensively in Benguet, Bontoc, Isabela, and Nueva Vizcaya, codified and reviewed early attempts to catalogue the indigenous peoples in The Non-Christian Tribes of Northern Luzon;[97] he collects "Calauas, Catanganes, Dadayags, Iraya, Kalibugan, Nabayuganes, and Yogades" into a single group of non-Christian "Kalingas" (an Ibanag term for 'wild men' – not the present ethnic group) with whom the lowland ("Christian") Gaddang are also identified.

"Members of the first governing commission were instructed “In all the forms of government and administrative provisions which they are authorized to prescribe, the commission should bear in mind that the government which they are establishing is designed not for our satisfaction, or for the expression of our theoretical views, but for the happiness, peace and prosperity of the people of the Philippine Islands, and the measures adopted should be made to conform to their customs, their habits, and even their prejudices, to the fullest extent consistent with the accomplishment of the indispensable requisites of just and effective government.[98]

When the U.S. took the Philippines from the Spanish in 1899, they instituted what President McKinley promised would be a "benign assimilation".[99] Governance by the U.S. military energetically promoted physical improvements, many of which remain relevant today. The Army built roads, bridges, hospitals, and public buildings, improved irrigation and farm production, constructed and staffed schools on the U.S. model, and invited missionary organizations to establish colleges.[100] Most importantly, these improvements affected the entire country, not just primarily the environs of the capital. The infrastructure improvements made great changes in the lives of the "Christianized" Gaddang in Nueva Vizcaya and Isabela (although they assuredly had a much smaller effect on the Gaddang in the mountains). The 1902 Land Act and the government purchase of 166,000 hectares of Catholic church holdings also affected the Cagayan Valley peoples.

In addition, the passage in 1916 of the Jones Act redirected almost all U.S. efforts in the Philippines, making them focus on a near-term when Filipinos would be in charge of their own destinies. This initiated promotion of social reforms from the Spanish traditions. Food safety regulations and inspection, programs to eradicate malaria and hookworm, and expanded public education were particular American projects that affected provincial Northern Luzon.[101] A practical decision was made to immediately conduct education in English, a practice finally discontinued only twenty-five years after independence.

During the first years of the 20th century, American administrators documented several cases throughout the islands of Filipino individuals being involved in the sale or purchase of Ifugao or Igorot women and girls to be domestic servants.[102]

In 1903 the Senior Inspector of Constabulary for Isabela wrote to his superiors in Manila: "In this province a common practice to own slaves... Young boys and girls are bought at around 100 pesos, men (over) 30 years and old women cheaper. When bought (they) are generally christened and put to work on a ranch or in the house... Governor has bought three. Shall I investigate further?"[103]

The regular sale of "non-Christian" Cordilleran and Negrito tribesfolk to work as farm labor in Isabela and Nueva Vizcaya was documented (a practice noted even during the Spanish administration[104]), and several Gaddang were listed as purchasers.[105][106] While household slaves often were treated as lesser members of Filipino families, problems was exacerbated by sale of slaves to Chinese residents doing business in the Philippines. When Governor George Curry arrived in Isabela in 1904, he endeavored to enforce the Congressional Act prohibiting slavery in the Philippines but complained the Commission provided no penalties. The practice — considered to be of centuries-long standing — was effectively discouraged de jure by 1920.

In 1908, the Mountain Province administrative district was formed, incorporating the municipality of Natonin, and its barangay (now the municipality) of Paracelis on the upper reaches of the Mallig River, as well the Ifugao municipality of Alfonso Lista uphill from San Mateo, Isabela. These areas were the home of the Ga'dang-speaking Irray and Baliwon peoples, mentioned in the early Census as "non-Christian" Gaddang. A particular charge of the new province's administration was the suppression of head-hunting.[100]

In 1901, the U. S. Army began to recruit counter-insurgency troops in the Philippines. Many Gaddang took advantage of this opportunity, and joined the Philippine Scouts as early as 1901 (more than 30 Gaddang joined the original force of 5,000 Scouts), and continued to do so through the late 1930s. The Scouts were deployed at the Battle of Bataan,[107] most were not in their homelands during the Japanese Occupation. One Gaddang 26th Cavalry private, Jose P. Tugab, claimed he fought in Bataan, escaped to China on a Japanese ship, was with Chiang Kai-shek at Chunking and US/Anzac forces in New Guinea, then returned to help free his own Philippine home.[108]

Japanese incursion and WWII

The Japanese undertook a policy of economic penetration in the Philippines immediately after the American occupation began. It concentrated on acquiring land in agriculturally under-developed areas in Northern Luzon and Mindanao,[109] while also emplacing Japanese nationals throughout the country.[110] Beginning in 1904, construction at Baguio attracted more than 1,000 Japanese nationals - who eventually acquired farms, retail, and transport businesses.[111] Land ownership under the Public Land act of 1903 (P.L. 926) by Japanese nationals in the Philippines exploded to more than 200,000 hectares; the Commonwealth government became concerned enough about Japanese corporate land-ownership to initiate the Land-Act of 1919 (P.L. 2874), restricting land ownership to situations where more than 60% of ownership were Philippine or United States citizens.[112] By the late 1930s, more than 350 registered Japanese-owned businesses – 80% with ten or fewer employees, and 19,000 Japanese nationals were established in the Philippines. Prior to December 1941, most municipalities in northern Luzon housed at least one Japanese-owned business whose proprietor's primary loyalty was to his homeland. Very few were spies, but they provided a stream of vital political, economic, and logistical information to those who were.[113]

On December 10, 1941, elements of the Japanese 14th Army landed at Aparri, Cagayan and marched inland to take Tuguegarao by the 12th. Hapless regular Philippine Army (PA) units of the 11th Division surrendered or fled. While Gen.Homma's main force proceeded to Ilocos Norte along the coast, troops were deployed to administer the agriculturally rich Cagayan Valley and facilitate Japanese appropriation of food supplies (butchering of more than half of farmers' carabao for meat to feed their army[114]) and farm equipment. Retreating US military destroyed communications infrastructure to prevent use by the Japanese invaders.[115] By late 1942 reliable information, food, and other commodities for native residents of the Cagayan Valley region had become very scarce.[116]

Meanwhile, the Manila-based Second Philippine Republic of President Laurel encouraged collaboration with the Japanese. In these hard times for North Luzon, many individual Japanese soldiers established relationships with Filipino residents, married local women, and fathered children with the expectation of becoming permanent (if superior) residents. Philippine and American military escapees hid in the mountains or valley villages; some engaged in small-scale guerrilla actions against the Japanese. In October 1942, American Colonels Martin Moses and Arthur Noble attempted a coordinated Northern Luzon guerrilla action which failed.[117] Japanese forces in the Cagayan Valley perceived a serious threat, and brought thousands of troops from Manila and Bataan to discourage possible resistance in a fierce and indiscriminate manner. "(Local) leaders were killed or captured, civilians were robbed, tortured, and massacred, their towns and barrios were destroyed."[117]

Surviving American Capt. Volckmann re-organized guerilla operation into the United States Army Forces in the Philippines – Northern Luzon (USAFIP-NL) in 1943 with a new focus on gathering intelligence. Based in the Cordilleras, his native forces (including several Gaddang) were effective, even though they ran great risks,[118] providing USAFFE information about Japanese troop dispositions. Capt. Ralph Praeger operated semi-independently in the Cagayan Valley, supported by Cagayan Governor Marcelo Adduru,[119] before his "Cagayan-Apayo Force" (Troop C, 26th Cavalry) was destroyed in 1943. USAFIP forces also coordinated with American forces in the 1945 Battle of Luzon.

The final stages of the war in the Philippines took place in the Cagayan and the Cordilleras. After recapturing central Luzon, American forces turned to the Cordilleras and Caraballos to pursue General Yamashita's forces. The main Japanese force retreated into the mountains at Kiangan, seizing food and supplies from the Magat valley.[120] Taking Baguio and Balete Pass by the end of May (with locals assisting on the flanks), U.S. infantry reached Bayombong in a week, Bagabag a day later, and Santiago on June 13; by June 26, the Americans met a U.S. force heading south to Tuguegaro.[121] Local guerillas destroyed the Bagabag-Bontoc Road bridges, stopping further supplies for Japanese in the mountains; infantry followed through Oriung Pass chasing Japanese west into the Cordilleras. As forces from Bagabag fought uphill towards Kiangan, a USAFIP force (including guerillas) drove east from Cervantes to reduce the Japanese stronghold.[122] By mid-August, the eight-month struggle for Luzon was over, it concluded with Yamashita's surrender in early September.

The effects of the war on the Filipino population were not well-documented or understood.[123] Fatalities due to military action, starvation, lack of medical care, and mistreatment of civilians are merely estimates - 5% of the 1939 census is a mean.[124] In Isabela and Nueva Vizcaya that fraction would come to about 15,000 dead, and as many wounded or homeless.[125] Any documented loss of infrastructure (communications, roads & buildings lost to military action, schools closed, farmlands uncultivated, animals destroyed) also remains unavailable, but it's understood there were substantial losses. Finally, collaborators were severely resented and criticized for opportunism and oppression.[126]

Post-WWII

On October 22, 1946,the Treaty of Manila established the independent Republic of the Philippines.[127] Quickly ratified by the U.S. Senate and signed by President Harry Truman; it left a newly-created nation that faced enormous challenges. "The close of the war found the Philippines with most of its physical capital demolished or impaired. Transportation and communication facilities were severely damaged, and agricultural production seriously depleted".[128]

National political and economic developments immediately affected the Gaddang "homelands" in the Cagayan watershed. Access to northern Luzon was compromised by Hukbalahap activity in Bulacan and Nueva Ejica from 1946 to 1955, delaying infrastructure repair and development. While the economy improved under President Quirino, it was mostly due to reconstruction grants from the U.S.,[129][130] with benefits focused on metro Manila.[131] The financial situation was exacerbated when President Garcia's 1958 National Economic Council Resolution No. 202 created major disincentives to foreign investment.[132] Global recession and commodity price-inflation followed the Vietnam war. The 20-year dictatorship of Marcos saw corruption and looting on an unprecedented scale,[133] and an Ilokano political ascendancy in Region II.[134] By the 1986 election, the nation was in a debt-crisis with a very high incidence of severe poverty.[135] In following years - from 1986 to 2016 - the country has had a revolution, a new Constitution, five presidential administrations (none of which represented an electoral majority), and a successful presidential impeachment.

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1948 | 402,000 | — |

| 1970 | 961,000 | +4.04% |

| 1995 | 1,821,000 | +2.56% |

| 2020 | 2,702,000 | +1.59% |

| Source: Philippine Statistics Authority | ||

The population of the Philippines at independence was less than 17 million.[136][137] By 2020, the Philippine Census passed 112 million,[138] forecast to grow to 200 million in the next forty years,[139] even after losing large numbers of Filipino permanent emigrants to other countries.[140] In the essentially-rural Gaddang "homelands" (Isabela, Nueva Vizcaya, and Quirino, plus adjoining municipalities in Cagayan and Mountain provinces) the rate of increase has surpassed the national level driven by the growth of large cities. The effects of population changes on Gaddang communities: (a) enormous numbers of people relocated to the previously-uncrowded Magat/Cagayan valleys from other parts of the country,[141] overwhelming original populations and regionally available resources to accommodate and integrate them; while (b) improved school facilities and resources have enabled educated indigenes to emigrate.[142] Over fifty years, this population-shift swamped the indigenous Cagayan cultures.

Growth in Northern Luzon was facilitated by infrastructure development. In 1965, President Macapagal proposed a Pan-Philippine highway;[143] the idea was adopted by his successor Marcos as part of his ambitious (and self-serving) program of public works.[144] The "Maharlika Highway," was implemented by making improvements to and connections between existing roads previously administered by Department of Public Works, Transportation and Communications.[145] Funding came from the World Bank, the Asian Highway project of the United Nations and a loan of more than US$30 million from Japan (segments were re-named the Philippine-Japanese Friendship Highway).[146] In Northern Luzon an important component was National Route 5 from Plaridel to Aparri,[147] built before WW2 by the US. Improvements to pavement, roadbeds, and bridges were completed by the mid-1970s and modestly maintained for several decades. In 1994, the Japanese provided another round of funding for improvements to accommodate significantly increased traffic in Luzon.[148] In 2004, the Philippines ratified the Intergovernmental Agreement on the Asian Highway Network, and the entire 3,500 km highway became AH26.[149]

Other major infrastructure projects in Northern Luzon in this period include the Magat Dam power, irrigation, and flood-control project undertaken during the Marcos administration and financed by loans from the World Bank.[150] The national telecommunications network originally built by American firm GTE[115] (though largely destroyed by US forces during WW2) was restored to pre-war levels by the 1950s. Japanese Overseas Economic Cooperation Fund loans were used in the 1980s for the Northern Luzon Communication Network Development Plan, providing telecommunications equipment to provide trunk cabling, microwave transmission equipment and major maintenance for extant infrastructure between 1983–1992.[151]

During the American occupation, education in the Gaddang homelands was generally available for elementary grades 1-6. By the 1930s provincial rural high-schools were established providing education in forestry and market-agriculture,[152][153] to introduce new crops and technologies. Catholic missionary high-schools were founded in several larger municipalities, and a private high-school was established in Santiago City a few months prior to the Japanese invasion of 1941.[154] After the war, some of these schools were encouraged to add "college-departments", providing teacher, commerce, engineering, and nursing training and degrees. Early establishments included Ateneo de Tuguegarao (1947), St. Mary's College in Bayombong (1947), Santiago City's Northeastern College (1948), and Saint Ferdinand College in Ilagan City (1950). Additional resources were devoted to some rural schools, enabling them to provide college-level instruction in mechanics and agriculture.[155] By the 1990's, a four-year high school education was available to every child in Isabela and Nueva Vizcaya; vocational education was being organized under the Technical Education And Skills Development Authority (TESDA);[156] and more than forty private and public colleges and universities offered education through post-graduate levels.[157]

Indigenous rights period

US occupation of the Philippines engendered massive re-evaluation of land-tenure based on grants to the Crown of Spain and the Church during the Spanish period; this introduced an early framework for concepts of collective indigene rights.[158] By 1919, P.L. 2874 incorporated recognition of advantages indigenous people accrued over Japanese, Chinese, and (non-US) foreign nationals.[112]

The World Council of Churches began in 1948, introducing a world-wide focus on the situation of threatened indigenous cultures; The World Council of Indigenous Peoples was founded in 1975. By the 1980s, a concern for activity addressing the rights of indigenous peoples around the world was being built into organizational missions of the United Nations, the World Bank, and the International Labor Organization.[159] The 1987 Constitution provides "an unprecedented recognition of indigenous rights to their ancestral domain" (Art.II,sec.22; Art XII,sec.5; Art.XIV,sec.17).[160]

In October 1997, the national legislature passed the Indigenous Peoples' Rights Act; the National Commission on Indigenous Peoples (NCIP) recognizes the Gaddang as one of the protected groups.[161] Initially, there was uncertainty about which peoples were to be recognized; the 2000 Census identified 85 groups[162] among which the Gaddang were included. Developments of political and administrative nature took several decades[163] and in May 2014 the Gaddang were recognized as "an indigenous people with political structure" with a certification of "Ancestral Domain Title" presented by NCIP commissioner Leonor Quintayo.[164] Starting in 2014 the process of 'delineation and titling the ancestral domains" was begun; the claims are expected to "cover parts of the municipalities of Bambang, Bayombong, Bagabag, Solano, Diadi, Quezon and Villaverde".[165] In addition, under the Indigenous Peoples Rights Act, certified indigenous peoples have a right to education in their mother-tongue; this education is as yet unimplemented by any organization with significant funding.

At present, a Nueva Vizcaya Gaddang Indigenous People's Organization has been formed, and by 2019 this group has been involved with coming to an agreement with agencies developing irrigation projects in Bayombong and Solano.[166] The organization is also actively pursuing cultural expositions.[167] There will inevitably be conflicts between the assertion of Gaddang rights and growth-driven development;[168] in Nueva Vizcaya the attempts of OceanaGold to continue mining despite the expiration of their permit and active legal opposition directly affects the Gaddang homelands.[169] With a population today not significantly larger than estimated by Fr. Antolin in the 1780s, the future of the Gaddang people remains a question.

Culture

Language

The Philippines National Commission for Culture and the Arts speaks of "five recognized dialects of Gaddang (Gaddang proper, Yogad, Maddukayang, Katalangan, and Iraya)",[170] more distantly-related to Ibanag, Itawis, Malaueg, and others.[171] Gaddang is distinct because it features phonemes (the "F", "V", "Z", and "J" sounds) not often present in many neighboring Philippine languages.[172] There are also notable differences from other languages in the distinction between "R" and "L", and the "F" sound is a voiceless bilabial fricative, and not the fortified "P" sound common in many Philippine languages (but not much closer to the English voiceless labiodental fricative, either). The Spanish-derived "J" sound (not the "j") has become a plosive. Gaddang is noteworthy for the common use of doubled consonants (e.g.: pronounced Gad-dang instead of Ga-dang).

Gaddang is declensionally, conjugationally, and morphologically agglutinative, and is characterized by a dearth of positional/directional adpositional adjunct words. Temporal references are usually accomplished using context surrounding these agglutinated nouns or verbs.[173]

The Gaddang language is identified in Ethnologue,[174] Glottolog,[175] and is incorporated into the Cagayan language group in the system of linguistic ethnologist Lawrence Reid.[176] The Dominican fathers assigned to Nueva Viscaya parishes produced a vocabulary in 1850 (transcribed by Pedro Sierra) and copied in 1919 for the library of the University of Santo Tomas by H. Otley Beyer.[177] In 1965 Estrella de Lara Calimag interviewed elders in the US and the Philippines to produce a word-list of more than 3,200 Gaddang words included in her dissertation at Columbia.[178] The Austronesian Basic Vocabulary Database lists translations of more than two hundred English terms on its Gaddang page.[179]

Daily use of Gaddang as a primary language has been declining during the last seventy years.[180] During the first years of the American occupation, residents of Nueva Vizcaya towns used to schedule community events (eg: plays or meetings) to be held in Gaddang and the next day in Ilokano, in order to ensure everyone could participate and enjoy them.[181] Teachers in the new American schools had to develop a curriculum for pupils who spoke entirely different languages:

Ilocanos, Gaddanesaa (sic), and Isanays; the latter coming from the Dupax section. There was no one language that all could understand. A few spoke, read, and wrote Spanish fluently...to the others Spanish was as strange a tongue as English.[182]

The use of English in the schools of Isabela and Nueva Vizcaya, as well as in community functions, was only discouraged with the adoption of the 1973 Constitution and its 1976 amendments.[183][184] A more urgent push to nationalize language was made in the 1987 Constitution, which had the unanticipated effect of marginalizing local languages even further. Television and official communications have almost entirely used the national Filipino language for nearly a generation.

Highlands culture

Many writers on tourism and cultural artifacts appear enamoured of the more-exotic cultural appurtenances of the highlands Gaddang (Ga'dang), and pay little attention to the more-numerous "assimilated" Christianized families.[185] Their narrative follows from the initial American assumption that lowland Gaddang originated with the highlands groups who subsequently became Christianized, then settled in established valley communities, acquiring the culture and customs of the Spanish, Chinese, and the other lowlands peoples. Many of them also distinguish the Gaddang residents of Ifugao and Apayo from other mountain tribes primarily by dress customs without considering linguistic or economic issues.[186] It is undeniable, however, that the "transactional" daily life of ordinary highlands Gaddang is enough different from that of their lowlands relations to identify them as culturally-distinct.[187]

Dedman College (Southern Methodist University) Professor of Anthropology Ben J. Wallace has lived among and written extensively about highland Gaddang since the 1960s.[188][189] His recent book (Weeds, Roads, and God, 2013) explores the transition these traditional peoples are making into the modern rural Philippines, taking on more customs and habits of the lowlands Gaddang, and discarding some colorful former behaviors.

Through the end of the 20th century, some traditional highlands Gaddang practiced kannyaw – a ritual including feasting, gift-giving, music/dance, ancestral recollections and stories – similar to potlatch – which was intended to bring prestige to their family.[190]

The tradition of taking heads for status and/or redressing a wrong appears to have ended after WWII, when taking heads from the Japanese seems to have been less satisfactory than from a personal enemy. Both men and women lead and participate in religious and social rituals.[191]

Class and economy

Interviews in the mid-20th century identified a pair of Gaddang hereditary social classes: kammeranan and aripan.[178] These terms have long fallen into disuse, but comparing old parish records with landholdings in desirable locations in Bagabag, Bayombobg, and Solano indicates that some real effects of class distinctions remain active. The writer's Gaddang correspondents inform him that aripan is similar in meaning to the Tagalog word alipin ("slave" or "serf"); Edilberto K. Tiempo addressed issues surrounding the aripan heritage in his 1962 short story To Be Free.[192]

During the first decades of the American occupation, a major effort to eradicate slavery terminated the widespread practice of purchasing Igorot and other uplands children and youths for household and farm labor. Many of the individuals so acquired were accepted as members of the owner-families (although often with lesser status) among all the Cagayan Valley peoples. Present-day Gaddang do not continue to regularly import highland people as a dependent-class as they did until a generation ago. There still remains the strong tradition of bringing any unfortunate relatives into a household, which frequently includes a reciprocal geas on beneficiaries to "earn their keep".

There does not seem to have been a Cagayan Valley analogue of the wealthy Central Luzon landowner class until the agricultural expansion of the very late nineteenth century; most of those wealthy Filipinos were of Ilokano or Chinese ancestry.

Records over the last two centuries do show many Gaddang names as land and business owners, as well as in positions of civic leadership.[193] The Catholic church also offered career opportunities. Gaddang residents of Bayombong, Siudad ng Santiago, and Bagabag enthusiastically availed themselves of the expanded education opportunities available since the early 20th century (initially in Manila, but more recently in Northern Luzon), producing a number of doctors, lawyers, teachers, engineers, and other professionals by the mid-1930s. A number also enlisted in the U.S. military service as a career (the U.S. Army Philippine Scouts being considered far superior to the Philippine Army).

Status of women and minor children

Lowlands Gaddang women regularly own and inherit property, they run businesses, pursue educational attainment, and often serve in public elected leadership roles. Well-known and celebrated[194] writer Edith Lopez Tiempo was born in Bayombong of Gaddang descent. There appear to be no prevailing rules of exogamy or endogamy which affect women's status or treatment. Both men and women acquire status by marriage, but there are acceptable pathways to prestige for single women in the Church, government, and business.[195]

The Philippines has enacted significant gender-equality legislation since the 1986 People Power Revolution, including Republic Acts 7192 (establishing the Gender and Development Budget), and 7877 (criminalizing sexual harassment). Women were beneficiaries of the 1988 Agrarian Reform and the 1989 Labor Code. Republic Act 6972 also specifies parental and state responsibilities for minor children. The Constitution includes this statement (Article II, section 14):

the State recognizes the role of women in nation-building and shall ensure the fundamental equality before the law of women and men.[196]

Such legislation directly affects education, workforce practices, land ownership. and politics. At the same time, a heritage of patriarchal colonialism, traditional practices, war and poverty has engendered traditional practices which have subjected women in Northern Luzon to exploitation, discrimination, and violence. Progress has indubitably been made, but more remains to be done.[197]

Kinship

The Gaddang as a people have lacked a defined and organized political apparatus; in consequence, their shared-kinship is the means of ordering their social world.[198] During their pre-Conquest days, their swidden economy forced a small population to be dispersed in a fairly large area. In a period where hostilities were a recurring phenomenon, expressed in head-taking and revenge, kinship obligations were the linkage between settlements; such kin-links include several (like solyad – or temporary marriage) which have no counterparts in modern law.[199]

As has been documented with other Indo-Malay peoples,[200] Gaddang kin relationships are highly ramified and recognize a variety of prestige markers based on both personal accomplishment and personal or social obligations that frequently transcend generations.[201] While linguistically there appear to be no distinctions beyond the second degree of consanguinity, tracing common lineal descent is important, and the ability to do so is traditionally admired and encouraged.[82] Relationships are traced through both patrilineal and matrilineal descent,[202] but may also include compadre/co-madre links (often repeated across several generations),[203][204] and even mentorship relationships.

It is unclear to what degree kinship-systems include mailan and other remnants of the slavery-system.

Funerary practices

Modern Christian Gaddang funerals are most commonly entombed in a public or private cemetery, following a Mass celebration and a procession (with a band if possible). A wake is held for several days before the services, allowing family members and friends travel-time to view the deceased in the coffin. Mummification is not usually practiced, but cremation – followed by entombment of the ashes – has been observed.

Supernatural traditions

Retelling stories of ghosts, witchcraft, and supernatural monsters (eg: the Giant Snake of Bayombong[205]) are a popular pastime, with the tellers most often relating them as if these were events in which they (or close friends/family) had participated. Various "superstitions" have been catalogued.[206]

While assertively Christian, lowland Gaddangs retain strong traditions of impairment and illness with a supernatural cause; some families continue to practice healing traditions which were documented by Father Godfrey Lambrecht, CICM, in Santiago during the 1950s.[207] These include the shamanistic practices of the mailan, both mahimunu (who function as augurs and intermediaries), and the maingal ("sacrificers" or community leaders–whom Lambrecht identifies with ancestral head-hunters).[208] The spirits that cause such diseases are karangat (cognates of which term are found among the Yogad, the Ibanag karango, and the Ifugao calanget); each being is associated with a physical locality and is considered the "owner" of the land;[209] they are not revenants; they are believed to cause fevers, but not abdominal distress. It is believed as well that Caralua na pinatay (ghosts) may cause illness to punish Gaddang who diverge from custom or can visit those facing their impending demise.

The upland "Pagan" Gaddang share these traditions, and in their animistic view, both the physical and the spiritual world are uncertain and likely hostile.[210] Any hurts which cannot be immediately attributed to a physical cause (eg: insect/animal bites, broken limbs, falls, and other accidents) are thought to be the work of karangat in many forms not shared with the lowlanders. They may include the deadly (but never-seen) agakokang which makes the sound of a yapping dog; aled who disguise themselves a pigs, birds, or even humans, infecting those they touch with a fatal illness; the vaporous aran which enters a person's brain and causes rapidly-progressing idiocy and death; or the shining-eyed bingil ghouls.[210] To assist their journey through such a dangerous world, the Gaddang rely on mediums they term mabayan (male mediums) or makamong (female), who can perform curative ceremonies.

Other folk-art traditions

Three hundred years of Spanish/Catholic cultural dominion – followed by a nearly effective revolution – have almost completely diluted or even eradicated any useful pre-colonial literary, artistic or musical heritage of the lowland Cagayan peoples, including the Gaddang.[205] Although the less-affected arts of the Cordillerans and some of the islanders south of Luzon are well-researched, even sixty years of strong national and academic interest has failed to uncover much tangible knowledge about pre-Spanish Cagayan valley traditions in music, plastic, or performing arts.[211] A review of Maria Lumicao-Lorca's 1984 book Gaddang Literature states that "documentation and research on minority languages and literature of the Philippines are meager"[212] That understood, however, there does exist a considerable record of Gaddang interest and participation in Luzon-wide colonial traditions, examples being Pandanggo sa ilaw, cumparsasa, and Pasyon;[191] while the rise of interest in a cultural patrimony has manifested in an annual Nueva Vizcaya Ammungan (Gaddang for 'gather') festival adopted in 2014 to replace the Ilokano-derived Panagyaman rice-festival.[213] The festival has included an Indigenous Peoples Summer Workshop, which has provincial recognition and status.[214]

Some early 20th-century travelers report the use of gangsa[215] in Isabela as well as among Paracelis Gaddang. This instrument was likely adopted from Cordilleran peoples, but provenance has not been established. The highlands Gaddang are also associated with the Turayen dance which is typically accompanied by gangsa.[216]

Most Gaddang seem fond of riddles, proverbs, and puns (refer to Lumicao-Lorca); they also keep their tongue alive with traditional songs (including many harana composed in the early parts of the 20th century). A well-known Gaddang language harana, revived in the 1970s and retaining its popularity today:[217]

|

|

Indigenous mythology

The Gaddang mythology includes a variety of deities:

- Nanolay – Is both creator of all things and a cultural hero. In the latter role, he is a beneficent deity. Nanolay is described in myth as a fully benevolent deity, never inflicting pain or punishment on the people. He is responsible for the origin and development of the world.

- Ofag – Nanolay's cousin.

- Dasal – To whom the epic warriors Biwag and Malana prayed for strength and courage before going off to their final battle.

- Bunag – The god of the earth.

- Limat – The god of the sea.[207]

Ethnography and linguistic research

While consistently identifying the Gaddang as a distinct group, historic sources have done a poor job of recording specific cultural practices, and material available on the language has been difficult to access.

Early Spanish records made little mention of customs of the Ibanagic and Igaddangic peoples, being almost entirely concerned by economic events, and Government/Church efforts at replacing the chthonic cultures with a colonial model.[219] The 1901 Philippine Commission Report states: "From Nueva Vizcaya, the towns make the common statement that there are no papers preserved which relate to the period of the Spanish government, as they were all destroyed by the revolutionary government."[220] American occupation records, while often more descriptive and more readily available, perform only cursory discovery of existing behaviors and historic customs, since most correspondents were pursuing an agenda for change.

Records maintained by churches and towns have been lost; in Bagabag they disappeared during or after the 1945 defense of the area by the Japanese 105th division under Gen. Konuma;[221] a similar claim has been made for losses during Japanese occupation of Santiago beginning in 1942, and the USA-FIP liberation efforts of 1945.[222] In Bayombong, St. Dominic's Catholic church (built in 1780) – a traditional repository for vital records – was destroyed by fire in 1892, and again in 1987.[223]

In 1917 the Methodist Publishing House published Himno onnu canciones a naespirituan si sapit na "Gaddang (a set of hymns translated into Gaddang). In 1919, H. Otley Beyer had the Dominican Gaddang-Spanish vocabulary[224] copied for the library at University of Santo Tomas; the offices at St. Dominic's, Bayombong are presently unable to locate the original document. In 1959, Madeline Troyer published an 8-page article on Gaddang Phonology,[225] documenting work she had done with Wycliffe Bible Translators.

Father Godfrey Lambrecht, the rector of St. Mary's High School & College 1934–56, documented a number of linguistic and cultural behaviors in published articles.[226][227][228] Several Gaddang have been pursuing family and Gaddang genealogy, including Harold Liban, Virgilio Lumicao, and Craig Balunsat.

During the late 1990s, a UST student attempted an "ethnobotanical" study, interviewing Isabela-area Gaddang about economically useful flora;[229] this included notes on etymologic history and folk-beliefs.

Notes

- "It is commanded: that all (Cagayan river-valley natives) must speak the language of Ibanag; and that (servants of the Church) will strive to serve the Indians in that tongue."

References

- 2010 Census of Population and Housing, Report No. 2A: Demographic and Housing Characteristics (Non-Sample Variables), Philippines (PDF) (Report). National Statistics Office. 2013. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- "Gaddang". Ethnologue. Retrieved 15 July 2023.

- "Ga'dang". Ethnologue. Retrieved 15 July 2023.

- "Ga'dang,Baliwon in Philippines". Joshua Project. Retrieved 25 August 2023.

- "The Cagayan River Basin". ABS-CBN News. 23 October 2009. Retrieved 20 March 2014.

- Amano, Noel; Bankoff, Greg; Findley, David Max; Barretto-Tesoro, Grace; Roberts, Patrick (February 2021). "Archaeological and historical insights into the ecological impacts of pre-colonial and colonial introductions into the Philippine Archipelago". The Holocene. 31 (2): 313–330. Bibcode:2021Holoc..31..313A. doi:10.1177/0959683620941152. ISSN 0959-6836. S2CID 225586504.

- Prill-Brett, June (2003). "Changes in indigenous common property regimes and development policies in the northern Philippines" (PDF). RCSD International Conference. Politics of the Commons: Articulating Development and Strengthening Local Practices: 11–14. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 December 2021.

- "Imperata cylindrica". Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants | University of Florida, IFAS. Archived from the original on 12 December 2021. Retrieved 2 December 2022.

- Cariño, Jacqueline K (November 2012). "Philippines: Country Technical Note on Indigenous Peoples' Issues". IFAD. Retrieved 2 December 2022.

- Lewis, Henry T. (1984). "Migration in the Northern Philippines: The Second Wave". Oceania. 55 (2): 118–136. doi:10.1002/j.1834-4461.1984.tb02926.x. JSTOR 40330799. PMID 12313778.

- Lumicao-Lora, Maria Luisa (1984). Gaddang Literature. Quezon City: New Day Publishers. ISBN 971-10-0174-8.

- "History". Province of Cagayan Website. Retrieved 28 April 2013.

- Gatan, Marino (1981). Ibanag indigenous religious beliefs: a study in culture and education. p. 23.

- "Ibanag Dialect: Potent Factor in Cagayan's Evangelization". Retrieved 26 August 2023.

- "Family: Cagayan Valley". Glottolog 4.6.

- "Paper presenting three dialects (Christian Gaddang, Pagan Gaddang, Yogad) of Northern Luzon, Philippines" (PDF). SIL International – Philippines. March 1954. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 May 2022.

- Dita, Shirley (2010). A Referencce Grammar og Ibanag: Phonology, Morphology, & Syntax (Thesis).

- "Doctrine of Discovery Facts". Dismantling the Doctrine of Discovery. 6 December 2018.

- Deagan, Kathleen (2003). "Colonial Origins and Colonial Transformations in Spanish America". Historical Archaeology. 37 (4): 3–13. doi:10.1007/BF03376619. ISSN 0440-9213. JSTOR 25617091. S2CID 140497913.

- Pearson, M. N. (1969). "The Spanish 'Impact' on the Philippines, 1565–1770". Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient. 12 (2): 165–186. doi:10.2307/3596057. ISSN 0022-4995. JSTOR 3596057.

- Punzalan, Ricardo L. (2 August 2007). "Archives of the new possession: Spanish colonial records and the American creation of a 'national' archives for the Philippines". Archival Science. 6 (3–4): 381–392. doi:10.1007/s10502-007-9040-z. ISSN 1389-0166. S2CID 143864777.

- Guillermo, Artemio R. (2012). Historical dictionary of the Philippines (3rd ed.). Lanham, Md.: Scarecrow Press. p. 374. ISBN 978-0-8108-7511-1. OCLC 774293494.

- Dr. David P. Barrows (1905). "A History of the Population: Non-Christian Tribes". Census of the Philippine Islands: Geography, history, and population. U.S. Government Printing Office. pp. 448–449.

- Alip, Eufronio Melo (1964). The Philippines of yesteryears : the dawn of history in the Philippines. Alip. OCLC 491664055.

- Historia de Nueva-Vizcaya y provincia montanõsa / Por Fr. Julian Malumbres. 2005.

- Sawyer, Frederic H. (1900). The Inhabitants of the Philippines. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons.

- "File:Locations Important in Gaddang History.png - Wikipedia". commons.wikimedia.org. 24 February 2022. Retrieved 20 May 2023.

- Beyer, H. Otley (1917). Population of the Philippine Islands in 1916 (población de las islas Filipinas en 1916). Manila: Philippine Education Co., Inc. p. 22.

- Llamzon, Teodoro (1966). "The Subgrouping of Philippine Languages". Philippine Sociological Review. 14 (3): 145–150. JSTOR 23892050.

- Scott, William Henry (1979). "Semper's 'Kalingas' 120 years later". Philippine Sociological Review. 27 (2): 93–101. JSTOR 23892117.

- Beyer, H. Otley (1917). Population of the Philippine Islands in 1916 (población de las islas Filipinas en 1916). Manila: Philippine Education Co., Inc.

- Lambrecht, Godfrey (1959). "The Gadang of Isabela and Nueva Vizcaya: Survivals of a Primitive Animistic Religion". Philippine Studies. 7 (2): 194–218. JSTOR 42719440.

- 1960 Population and Housing Report, Bureau of Census

- "Philippine Peoples: Gaddang". Archived from the original on 17 July 2013. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- ISSN 0116-2640

- Archived 2021-07-23 at the Wayback Machine | page 7

- "Paleolithic Archaeological Sites in Cagayan Valley". UNESCO World Heritage Centre – Tentative List. Archived from the original on 10 February 2021. Retrieved 2 December 2022.

- Hung, Hsiao-Chun; Iizuka, Yoshiyuki; Bellwood, Peter; Nguyen, Kim Dung; Bellina, Bérénice; Silapanth, Praon; Dizon, Eusebio; Santiago, Rey; Datan, Ipoi; Manton, Jonathan H. (11 December 2007). "Ancient jades map 3,000 years of prehistoric exchange in Southeast Asia". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 104 (50): 19745–19750. doi:10.1073/pnas.0707304104. PMC 2148369. PMID 18048347.

- "Excavation at Nagsabaran: An early village settlement in the Cagayan Valley of Northern Luzon, Philippines". School of Archaeology and Anthropology – Australian National University. 10 October 2009.

- Larena, Maximilian; et al. (30 March 2021). "Multiple migrations to the Philippines during the last 50,000 years". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 118 (13). Bibcode:2021PNAS..11826132L. doi:10.1073/pnas.2026132118. PMC 8020671. PMID 33753512.

- Heaney, Lawrence R. (1998). "The Causes and Effects of Deforestation". Vanishing treasures of the Philippine rain forest. Jacinto C. Regalado, Field Museum of Natural History. Chicago: Field Museum. ISBN 0-914868-19-5. OCLC 39388937.

- West, Barbara A. (2009). Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Asia and Oceania. New York: Facts On File. p. 299. ISBN 978-0-8160-7109-8.

- Swidden cultivation in Asia. UNESCO Regional Office for Education in Asia and the Pacific. 1983. OCLC 644540606.

- Turner, Frederick Jackson (1921). The frontier in American history. New York : H. Holt.

- Valdepeñas, Vicente B.; Bautista, Germelino M. (1974). "Philippine Prehistoric Economy". Philippine Studies. 22 (3/4): 280–296. JSTOR 42634874.

- Peter S. Bellwood (2015). The global prehistory of human migration (Paperback ed.). Chichester, West Sussex. p. 213. ISBN 978-1-118-97058-4. OCLC 890071926.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Cagayan. "Arts and Culture". Cagayan.gov.ph. Retrieved 24 April 2013.

- "Filipino Cultures". AFS – USA. Archived from the original on 9 March 2022.

- "Philippines". Hofstede Insights. Retrieved 2 December 2022.

- Gallego, Maria Kristina S. (2015). "Philippine Kinship and Social Organization from the Perspective of Historical Linguistics". Philippine Studies: Historical & Ethnographic Viewpoints. 63 (4): 477–506. doi:10.1353/phs.2015.0046. ISSN 2244-1093. JSTOR 24672408. S2CID 130771530.

- Molintas, Jose Mencio (2004). "The Philippine Indigenous Peoples' Struggle for Land and Life: Challenging Legal Texts [Article]". Arizona Journal of International and Comparative Law. ISSN 0743-6963.

- Junker, Laura Lee (1990). "The Organization of Intra-Regional and Long-Distance Trade in Prehispanic Philippine Complex Societies". Asian Perspectives. 29 (2): 167–209. ISSN 0066-8435. JSTOR 42928222.

- Solheim, Wilhelm G. (2006). Archaeology and culture in Southeast Asia : unraveling the Nusantao. David Bulbeck, Ambika Flavel. Diliman, Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press. p. 316. ISBN 971-542-508-9. OCLC 69680280.

- Chua, Amy (2007). Day of empire : how hyperpowers rise to global dominance-- and why they fall. New York: Anchor Books. p. 123. ISBN 978-0-307-47245-8. OCLC 818889119.

- General Archive of the Indies, Philippines, file 29, bunch 3, number 62. Letter from Juan Bautista Román to the Viceroy of México, 25th of June, 1582

- Lambrecht, Fr Francis (1964). "The Ethnohistory of Northern Luzon by Felix M. Keesing. Stanford University Press, Stanford, 1962. Pp. 362, maps". Journal of Southeast Asian History. 5 (1): 202–205. doi:10.1017/S0217781100002313. ISSN 0217-7811.

- Ember, Melvin; Ember, Carol R.; Skoggard, Ian (30 November 2004). Encyclopedia of Diasporas: Immigrant and Refugee Cultures Around the World. Volume I: Overviews and Topics; Volume II: Diaspora Communities. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-0-306-48321-9.

- Mawson, Stephanie Joy (1 January 2014). Between Loyalty and Disobedience: The Limits of Spanish Domination in the Seventeenth Century Pacific (Thesis thesis).

- García-Abásolo, Antonio (1998), Spanish Settlers in the Philippines (1571–1599) (PDF)

- Phelan, J. L. (1959). The Hispanization of the Philippines: Spanish Aims and Filipino Responses 1565–1700. Madison: University of Wisconsin.

- Newson, Linda A. (1999). "Disease and immunity in the pre-Spanish Philippines". Social Science & Medicine. 48 (12): 1833–1850. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00094-5. PMID 10405020.

- Wallace, Ben J. (2013). Weeds, Roads and God : a Half-Century of Culture Change among the Philippine Ga'dang. Long Grove, Illinois. ISBN 978-1-57766-787-2. OCLC 800027025.