Free Senior High School

The Free Senior High School (Free SHS) education policy in Ghana was a government initiative introduced in the 2017 September Presidential administration of Nana Akufo-Addo.[1] The policy's origination began as part of the President's presidential campaign during Ghana's 2016 election period, and has become an essential part of Ghana's educational system.[2] The policy's core themes of access, equity and equality fulfil the United Nations modified Sustainable Development Goals, where member countries amalgamate those themes in their educational systems to certify adequate learning experiences for students.[3] Respective politicians and social workers have been allocated the duty to ensure the policy's efficiency, productivity and further development. These leaders span from varying governmental departments including Ghana's Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning and Ghana Education Service and Ghana's Ministry of Education.[2]

| Ghana Ministry of Education | |

|---|---|

| President | Nana Akuffo-Addo |

| General details | |

| Primary languages | English,Ewe,Twi,Fante,Ga, Dagbani |

| System type | Educational |

| Established | 2017 |

Rationale for the policy

A review of Ghana's former high school policies and operations led to the essential creation of Free SHS. Ghana's Ministry of Education, observed the lack of efficiency in key areas; access to education, quality of education, and education management.[4] The fifth Education Strategic Plan targeted for 2010 to 2020, outline the government's key educational objectives.[5] These objectives influenced by Ghana's 2008 Education Act, are implemented in the policy to regulate these legislative solutions.[4]

Since Ghana's Independence in 1957, a series of reformations have been made to the educational system to restructure colonial and foreign models to suit Ghanaian people, culture and customs.[6] These amendments were what was deemed an appropriate educational model for the newly decolonized state. The 1951 Accelerated Development Plan (ADP) was established to attain the notion of ‘universal primary education’ with measures to abolish tuition fees and increase enrolment.[7] The financial strain on households was not entirely lifted as the expenses of school supplies such as books and stationery was the responsibility of parents and guardians. The scarce availability of trained teachers and minimal financing of suitable schooling infrastructure caused the inability of the ADP to withstand as a long lasting program.[7]

Further educational developments included the legislation of Universal Primary Education in 'The Education Act of 1961', the modifications of the 'National Liberation Council', the 'New Structure and Content of Education of 1974', and the New Educational Reform of 2007.[6]

Policy Demographic

Although the incentive is accessible for all high school students, the demographic the policy aimed to benefit the greatest were those in rural and disadvantaged communities. The policy has supported other practical governmental contributions to the livelihoods of poorer students and their families.[8] Initially, high achieving students in these areas were awarded simply with scholarship and internship opportunities. The policy in its broad accessibility has formed more equitable means of improving the proportion of marginal to inframarginal expenditure in high school educational funding and educational opportunities.[9]

Responses

Response

In the policy's initial introduction into the public sphere, there was disapproval due to a lack of understanding of its nature. Commotion concerning increasing upper-class taxes and adding pressure onto middle class and lower class students to achieve higher than already expected grades. Fears of failures to adequately distribute resources and funds could have posed further risk of disadvantage for students already experiencing difficulties. Free SHS maximised literacy levels increased economic and social developments.[8] It has released parental demands of educational finances to shift to focusing on building their family's resilience and social welfare.[8] The initial negative social response transformed to overwhelming support, especially for its ability to deter adolescents from social vices to make impactful contributions to their local communities.[8]

Political Response

Governmental and non-governmental institutions as well as parliamentary allegiances, had to alleviate political viewpoints in the periods of creating and modifying the policy. Education as a shared custom between the parties was the focus amongst the socio-economic debates of the policy.[8] An imperative focus between political actors and influencers was created to provide quality as well as quantity in the introduction of education policies in Ghana. The demand for quality education previously became outweighed by political imperatives of political parties.[10] The respective parties in the formation of the SHS policy appealed to socialist beliefs and mechanisms to ensure that the policy would be collectively produced and managed without political prejudices over previous policies.[8]

Academic Response

Educational institutions have rightly so produced their own research on the resources, schools, teachers, and students to assess the effectiveness of the policy. The quantity of students now enrolled in Secondary High school in comparison to before the implementation of the policy where admission fees were essential for acceptance has substantially increased.[8] In the years 2017 and 2018 every student, especially those in the one third of public schools located in rural areas academically benefited from the policy.[8] Students were given free textbooks and other learning materials that would generally be applied to full scholarship recipients.[11]

Impact

Economic Impact

The anticipation for high school students to join career fields in the public sector that necessitate tertiary education, could now be further encouraged. A gap reduction has formed in university graduates who acquire degrees without the achievement of secondary studies. Previously, 70% of high school students that desired government employee positions by the age of 25 was realistically achieved by only 6% of that percentage.[9] Through the policy the labour market has expanded in diverse fields with more educated individuals to progress the nation's development,[9] Studies highlighted that students with higher economic capital in comparison to their economically disadvantaged peers are given an abundance of educational opportunities.[7] Promoting free high school education became an argument that it would fuel Ghana's economic growth[11] The Free SHS policy widens the eligibility and success rate of these educational opportunities with an aim for the individual to develop into a societal asset.

Political Impact

Policies that prioritise student welfare, encourages young people to be more politically conscious and engaged with political affairs.[9] It has built voter's confidence for a lot of senior high school students and their families where support for political parties are now reliant on recognised party results and not on party philosophies.[9] The non-discriminatory nature of the Free SHS policy has improved political awareness and functionality within Ghana, through its ability to be both a political promise to society and eventually become a successful product of it. It has encouraged citizen understanding and trustworthiness of taxation in the belief that the tax will directly contribute to financing the policy.[11] The Free SHS policy is a testament to modern day democratic politics where an initial intention results in an effective political impact, where policy and laws are executed in favour of the development of citizens and their society.[10]

Social Impact

The policy lifted the financial burden for most parents, who can now be more supportive in their child's academia without feeling dependent on scholarships or private benefits.[9] In aim to afford long term educational costs, lower income households commonly neglect the short term educational costs. Hence the tuition payment for parents and guardians was essential obligation and the purchasing of school equipment became secondary needs. The Free SHS policy covers the primary and secondary expenditure that caregivers were burdened to provide despite their economic incapability to do so.[11] Initially most parents would pay for secondary school tuition based on their own ability to understand their child's competency, but are now relieved of the social hindrance of choosing some children over others to be educated.[9]

Free SHS Secretariat

The secretariat was established by the Government of Ghana to enable the smooth running of the Free SHS program,[12] after calls of its establishment were made by The Ghana National Education Campaign Coalition.[13] Projects being embark by the secretariat includes : Senior High School Intervention Projects (SHSIPs),[14] School Feeding Extensions.[15]

Funding

The Government spent GH¢212 million from the Annual Budget Funding Amount (ABFA) in the first year of implementing the program.[16] The program have now been removed from the list of projects funded with the Annual Budget Funding Amount (ABFA).[17]

Financial controversy

See also (The proposed use of the Heritage Fund to implement the free SHS education policy)

The formation of the policy did not come without typical political and social backlash concerning as to how the funding for the policy will be collected and operated. President Nana Afuffo-Addo initially proposed for the system to be primarily funded by the government through re-adjustments of the national financial budget. Such plans was challenged by the IMANI Centre for Policy and Education who are a 'think tank' organization that provide policy research and advice to governments and governmental institutions.[19] The institution believed that the President's proposition would put at risk adequate funding for other government departments and political initiatives. The Senior minister of the Heritage Fund, Mr Yaw Osafo Marfo supported the President in using 9% of money the government's oil reserve to fund the first few years of the policy for it to become a stable program.[19] The minority leader of the Heritage Fund, Mr Haruna Iddrisu supported the advice of the IMANI Centre for Policy and Education, in preferring for that reserve money to be saved for a potential, economic or social crisis that could occur in Ghana. The President followed through with his decision to use the oil reserves.[19]

Implementation of the double track system

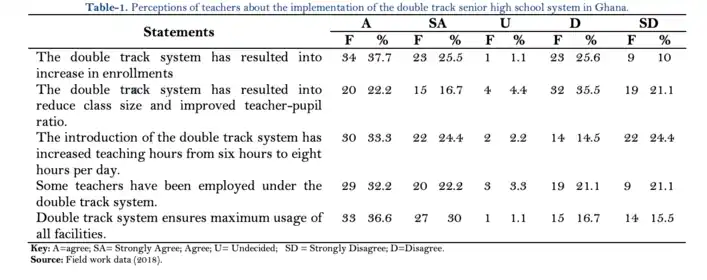

In 2018, Nana Akuffo Addo and his team of governance introduced another initiative as part of the Free SHS Education Policy which is the Double Track System.

The double track system was introduced by the government in order to enable various senior high schools to take in more students and ensure that all students have access to a senior high school education. The Double Track System is in two sessions, thus The Green Track and The Gold Track. The Green Track represents the first batch of students who would go to school for a semester and are later followed by the Gold Track students who would continue after students of the green track session have vacated on the academic calendar.[20]

The double track system is an exemplar of the extensions of the policy since its development. The system was introduced to combat the overwhelming number of high school enrollments that were as a result of the publicizing of the policy.[21] The main criticism of the system was how educators and school facility owners were not entirely consulted on the government's plans, which included the time frames their schools would be renovated and their accessibility to freelance funding.

Therefore, some improvements that were made could not entirely benefit the regions the system was specifically formed for, as while some still lacked in suitable equipment others had an abundance of it.[21] Its implementation nevertheless has seen the quality of educational resources such as improving the state of physical classrooms, reducing classroom congestion, and shortening schooling hours, contribute to the academic and social progression of students.[8] The temporary system was introduced in aim to create an advanced school functioning dynamic in accordance with the SDG target 4.[8]

Increase in Enrollments since the Implementation of the Double Track System

Effects of the COVID-19 Crisis on Free SHS

To minimize the spread of the SARS-CoV2 virus, the Ministry of Education (MoE) developed a closure and return to schools plan following the executive order of President Nana Kufo Addo, which ordered schools at all levels to close on March 20, 2020.[22] Initially some SHS3 students were to be allowed to continue preparing for their West African Senior School Certificate Examination, but shortly after all schools were closed entirely.[22] In addition the MoE ordered that, only the second year high school students should return to school to complete their second semester academic year, starting from 5 October 2020. A number of strategies were implemented to sustain education across levels despite closures, including lessons that were broadcast via television and radio segments across Ghana, as well as the development of some limited distance or e-learning platforms.[22]

In January 2021 (after a 10-month closure), by presidential order schools were reopened in Ghana with the requirement that schools monitor students infection status through temperature checks and all students wear masks at all times.[23]

References

- "President Akufo-Addo Launches Free SHS Policy". presidency.gov.gh. Retrieved 2020-05-26.

- Kyeremanteng, Harriet. (2016). Assessing stakeholder participation in policy formulation and implementation: The case study of the Free Senior High School Policy in Ghana. (PDF). The University of Ghana, Legon: pp.1-80. Retrieved 15 April 2020, from http://ugspace.ug.edu.gh/bitstream/handle/123456789/30912/ Assessing Stakeholder Participation in Policy Formulation and Implementation- The Case Study of the Free Senior High School Policy in Ghana.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 4 (SDG 4) | Education within the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. (2020). Retrieved 22 April 2020, from https://sdg4education2030.org/the-goal

- Ministry of Education. (2012). Education Strategic Plan 2010 to 2020. Government of Ghana. Retrieved 26 March 2020, from https://www.globalpartnership.org/content/government-ghana-education-strategic-plan-2010-2020-volume-1-policies-strategies-delivery pp.1-15

- Aheto-Tsegah, C. (2012). Education in Ghana – status and challenges. Retrieved 23 March 2020, from http://www.cedol.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/Charles-Aheto-Tsegah-article.pdf

- Adu-Gyamfi, Samuel; Donkoh, Wilhemina Joselyn; Addo, Anim Adinkrah (September 2016). Educational Reforms in Ghana: Past and Present. Journal of Education and Human Development. Vol. 5: pp. 158-172. Retrieved 20 April, from doi:10.15640/jehd.v5n3a17

- Akyeampong, K. (2009). Revisiting Free Compulsory Universal Basic Education (FCUBE) in Ghana. Comparative Education, 45(2), 175-195. doi:10.1080/03050060902920534

- Animah, G. (2018). The Impact of Free Senior High School (FSHS) on Rural Areas in Ghana. University of Birmingham International Development Department. pp.1-74. Retrieved 7 April 2020, from https://www.academia.edu/40117244/The_Impact_of_Free_ Senior_High_School_FSHS_on_Rural_Areas_in_Ghana?email_work_card=interaction-paper

- Duflo, Esther; Dupas, Pascaline; Kremer, Michael (October 14, 2019). The Impact of Free Secondary Education: Experimental Evidence from Ghana (PDF). The American Economic Association: pp. 1-105. Received 18 April 2020, from https://web.stanford.edu/~pdupas/DDK_GhanaScholarships.pdf

- Asumadu , E. (2019). Challenges and Prospects of the Ghana Free Senior High School (SHS) Policy: The case of SHS in Denkyembour District. pp. 1-25. Retrieved 7 May 2020, from http://ugspace.ug.edu.gh/bitstream/handle/123456789/30956/ Challenges and Prospects of the Ghana Free Senior High School %28SHS%29 Policy The Case of SHS in Denkyembour District..pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Adu-Ababio, K., & Osei, R.D (2018) : Effects of an education reform on household poverty and inequality: A microsimulation analysis on the free Senior High School policy in Ghana. WIDER Working Paper, No. 2018/147, ISBN 978-92-9256-589-3, pp. 1-19. The United Nations University World Institute for Development Economics Research (UNU-WIDER) doi:10.35188/UNU-WIDER/2018/589-3

- "The Free SHS Secretariat". FreeSHS. Retrieved 2019-11-12.

- "Education coalition proposes Secretariat for free SHS". www.myjoyonline.com. 2017-09-13. Retrieved 2019-11-12.

- "800 school facilities to ease SHS over-crowding by September". www.myjoyonline.com. Retrieved 2019-11-12.

- "Our nutrition Department monitors food quality – School Feeding PRO". Citi 97.3 FM - Relevant Radio. Always. 2017-10-17. Retrieved 2019-11-12.

- "Govt shifts Free SHS burden to Scholarship Secretariat". Graphic Online. 2018-01-30. Retrieved 2019-11-12.

- "No more oil cash for Free SHS". www.ghanaweb.com. Retrieved 2019-11-12.

- "Transfer of Free SHS funds to Scholarship Secretariat lawful – Gov't". Citi 97.3 FM - Relevant Radio. Always. 2017-12-22. Retrieved 2019-11-12.

- "Ghana: 'No Regrets for Using Oil Revenues to Fund Free SHS' - President Akufo-Addo". allAfrica.com. 2019-11-06. Retrieved 2020-05-28.

- "Double Track System". Ghana Web. Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- Mensah, D. (2019). Teachers’ Perspective on Implementation of the Double Track Senior High School System in Ghana. International Journal Of Emerging Trends In Social Sciences, 5(2), 47-56. pp. 47-56. doi:10.20448/2001.52.47.56

- "COVID-19 Coordinated Education Response Plan for Ghana" (PDF). Ghana Ministry of Education. 2020.

- "Schools in Ghana reopen as covid-19 cases surge". www.msn.com. Retrieved 2021-07-19.