Frederick Weston

Frederick Weston (1946–2020) was an American interdisciplinary artist. Self-taught, he worked in collage, drawing, sculpture, photography, performance, and creative writing. He was raised in Detroit, Michigan and moved to New York City in the mid-1970s. Over the course of his time in New York, he developed a vast, encyclopedic archive of images and ephemera related to fashion, the body, advertising, AIDS, and queer subjects through his various jobs and social presence in hustler bars and gay nightlife. His early collages and photography, which often utilized likenesses of patrons, highlighted the social and communal nature of such institutions. Continuing this theme, in the mid-1990s, he became co-founder of guerrilla artist group Underground Railroad, which produced street art and outdoor installations. In his lifetime, he exhibited to small audiences in non-traditional art spaces and only in the last two years of his life did his work become widely known and appreciated in urban art circles.

Frederick Weston | |

|---|---|

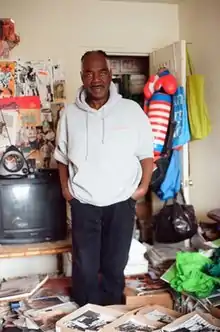

Weston in his apartment/studio, 2020 | |

| Born | Frederick Eugene Weston December 9, 1946 |

| Died | October 21, 2020 (aged 73) |

| Nationality | American |

Weston's early ambition to write fashion reviews for a living later took new life when an AIDS therapist encouraged him to express his feelings in poems. Reviewers later saw influences of his poetry in the collages he made. When the Foundation for Contemporary Arts gave him its Roy Lichtenstein Award in 2019, its announcement praised his collages as "a form of visual poetry, which explore individualism and the ways in which identity is shaped by community" and on the occasion of his first solo exhibition in a commercial gallery a curator wrote, "Weston embraces collage for its immediacy as a fluid form of tactile poetry".[1][2]

Weston was modest about the late recognition he received. In a 2019 interview he said, "I'm getting recognition as an artist now basically because I'm 73 and a professional AIDS patient who has managed to survive and has been practicing art all this time".[3]

Early life and education

Frederick Eugene Weston was born on September 9, 1946, in Memphis, Tennessee.[4] His mother, Freda Morman Weston, was 21 years old at the time and unmarried. While he was still a baby, Freda brought him to live with her parents, Fred and Emma Weston, in their home in Detroit. Fred was an autoworker and Emma a housewife. Weston later said that his grandparents were his main caretakers during his childhood. He called his grandparents "mother" and "daddy" and called his mother "Freda".[5] Weston had a large number of close relatives, the families of Freda's aunts and uncles and the children of a marriage she made while Weston was young. His father never recognized him as his child and Weston said he only saw him twice in his life.[5]

The household in which Weston was raised was literate and creative. He was read to and was himself an avid reader. An expert seamstress, his mother created much-admired women's fashions. He benefited from anti-segregation policies in education and was bused to integrated public schools in Detroit in which, he said, he felt comfortable and received a good education. A hard worker, he earned money doing odd jobs so that he could attend and eventually graduate from Ferris University. He liked student life there and helped found the university's first African-American fraternity.[5]

He spent his childhood in Detroit, Michigan, where his mother had moved soon after his birth.[2] As a child, he met his father only once and, due to the youth of his mother, he received most of his parental care from her parents' home. He was educated in integrated public schools and, while he was a student in Detroit's Commerce High School, one of his teachers encouraged him to pursue art as a career. However, when his mother emphatically told him he could never support himself as an artist, he did not pursue that recommendation.[5] Instead, he took business courses in high school and, after graduating, attended Ferris State University in the small mid-state city of Big Rapids where, in 1971, he obtained a B.S. degree with a major in marketing. Having learned to make clothing by watching his mother's highly skilled sewing technique, he designed clothing for himself while earning his living at an all-Black modeling agency in Detroit.[4]

In 1973, Weston moved to Manhattan where, failing to find work in the fashion industry, worked in low-paying off-the-books service jobs. In the early 1980s, he began study at the Fashion Institute of Technology, taking courses in menswear design and marketing.[4] He graduated from F.I.T. magna cum laude in 1985 with an A.A.S. degree.[1] He worked for a time with the African-American designer Stephen Burrows, but grew frustrated with the fashion industry's discriminatory practices and abandoned an ambition to become a professional fashion writer.[2] During the 1980s, he continued to survive on low-pay service jobs such as checking hats and coats at midtown gay bars, all the while collecting and organizing source material for the collages he had, by then, begun to make.[4][6] Although, as he later said, he had never learned to draw, by the middle of the 1990s an unexpected sequence of events led him to believe he could become a professional artist.[5]

In March 1995, Weston received a diagnosis as a victim of AIDS.[7] At the time, a friend directed him to the Gay Men's Health Crisis, an AIDS service organization in Greenwich Village. An acquaintance at GMHC suggested he become a participant in the AIDS Adult Day Health Care Program, located in the same building and run by a social services organization called Village Care of New York. On applying, Weston was accepted into the program and began participating in the Medicaid-supported services that it offered. As a participant, he received health services and substance-abuse counseling, and was given food he could take home thereby ensuring that he ate two meals a day (where before he only had one). He also received help toward obtaining financial assistance via the New York City welfare program and, significantly, was given encouragement and supplies for constructing art projects.[2][5][8]

In 1998, Weston brought photographs taken by a deceased friend to Visual AIDS, an organization that supports artists who have AIDS. Recognizing his artistic ability, the organization invited him to join the organization and participate in exhibitions it sponsored.[2][4][note 1]

Career in art

If I am not creating art, I am not living. Being able to create is real power.

Frederick Weston, Profile appearing on the website of Visual AIDS in 2008.[7]

At about the same time he became a participant in the AIDS Adult Day Health Care Program, Weston took an off-the-books nighttime job in a Midtown gay bar called Trix.[10] Weston mounted large panels on the walls of the coat-check cubicle where he worked with Polaroid images that he had taken of young gay men he had met at Trix whom he had dressed in second-hand clothing he had accumulated and assembled into outfits.[5] Weston later described Trix customers as "a fabulous mix of high and low and the best drag queens you ever saw".[11] Out of this collection of photographs he created what has been called his first solo exhibition.[4][6] In 1996, Trix relocated to another block in the midtown theater-district and changed its name to Stella's.[10] Continuing to run the coat-check operation there, Weston produced what has been called his second solo show. Called "Night Blooming Flowers", it was a selection from the display he exhibited at Trix.[11] An installation photo of this assemblage appears at left.

Weston picked up a low-wage clothing store job in the late 1990s where, as he said, "they were giving me a title (art director) because they weren't giving me any money". Asked to design a blue-themed presentation for the front of the store, he brought together a variety of empty containers he had collected, all of them painted blue, to simulate an abstract urban setting. When the shop's owner rejected the plan, he installed his project on the sidewalk in front of a blue barrier at a nearby construction site. This proved to be the first iteration of what became one of his best-known works, "Blue Bathroom Blues".[5][12] He drew the title from an evolving series of poems he had written first called "Blue Bedroom Ballads" and eventually "Blue Bathroom Blues". In presenting the poems, he included slides showing versions of the sidewalk art project. The project evolved from empty containers assembled outdoors to collages on foamcore made up of small slips of paper. These collages were similar to the photo boards he had first made while working at Trix.[5] A 1999 version of "Blue Bathroom Blues" is shown at right.

During this period, Weston continued to show collage projects in non-traditional gallery settings, including Village Care ("The Hats" and "I Am a Man" in 1999, as well as "Underground Railroad" in 2000), Stella's ("Presenting Stephanie Crawford" in 1997, and "Whatever Happened to Freddy Darling?" in 2003), the AIDS Housing Network Art Gallery ("The Lost Language of Men's Clothing" in 2002), and the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and, Transgender Community Center ("Go Figure" in 2002).[6][13]

In 2000, Weston showed a collage called "Little Black Sambo" at Village Care.[6] Like "Blue Bathroom Blues" this project evolved over a period of years. One version from 2006, called "Sambo Schema I", is shown at left. It is significant that the Sambo character in the children's book of the same name is a person of color from South India. Because many people who were labeled "Black" came from South India and other places in Asia as well as the biodiverse island of Madagascar, he resented the widespread practice of labeling all Black people African-American. Because of his dark skin color, Weston had to endure the taunt "African" during his childhood and as an adult, he rejected the label, saying "I don't know what I am. But I'm not African. I'm not from the deep dark jungles. I'm not a savage, you know. And that's what they taught us about Africa".[5] Weston knew that the Sambo story was seen as racist, but he did not read it that way. He said, "it's about clothes, and going somewhere you didn't have any business... when the fear's in my face and someone is threatening my life, can I use my wits, you know, to keep my life?"[5]

In a strange kind of way my dreams are always coming true and I'll usually wind up landing in very good places. And I really feel like I was blessed to have like all of it. I mean GMHC at the right time, AIDS Services at the right time, Village Care at the right time, and Visual AIDS at the right time. Stella's bar at the right time, Trix bar at the right time.

Frederick Weston, Oral history interview conducted for the Archives of American Art in 2016[5]

In 2003, Weston showed collages in a group exhibition called "Release" that was organized by Visual AIDS and appeared in the Museum of Contemporary African Diasporan Arts. Sally Block and Laurie Cumbo were its curators.[9] In 2011, he was given a retrospective exhibition called "For Colored Boys Who Have Considered Suicide When All You Ever Needed Was the Blues". It was held in the Rankin Art Gallery of Ferris State University.[14] Later that year, his work appeared in a group show called "Stay, Stay, Stay" sponsored by Visual AIDS at La MaMa La Galleria and three years later he showed with another group in Davidson College's Van Every Gallery.[15][16] Other group shows in this period included "Out of Bounds" at Leftfield Bar on the Lower East Side of Manhattan (2015), "Art AIDS America" at the University at Buffalo and three other sites (2016), and "Persons of Interest" at a Manhattan bookstore called Bureau of General Services—Queer Division.[6][17][18][note 2] He showed collages in four group shows during 2017 ("Intersectional Identities" at Clifford Chance in New York, "Found: Queer Archaeology; Queer Abstraction" at the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art in New York, and "AIDS at Home" at the Museum of the City of New York, "Cut Here: Matt Keegan, Siobhan Liddell, Frederick Weston" at the Gordon Robichaux Gallery).[6][19][20] The following year, he appeared frequently in group shows and in panel discussions in which he often showed slides of his work. These included a panel called "Fag, Stag, or Drag?" with John Neff at Artists Space in New York, a panel of poetry readings at Gordon Robichaux, a group show called "Proposals on Queer Play and the Ways Forward" at University of Pennsylvania's Institute of Contemporary Art, a panel on "Visual Arts and the AIDS Epidemic" at the Whitney Museum of American Art, a group called "This Must Be the Place" at the 44 Walker Street Gallery in New York, a group called "A Page from My Intimate Journal" at Gordon Robichaux, a group called "Queer Artist Fellowship: Alternate Routes" at the Leslie-Lohman Museum, and a two-person show called "Inside, Out Here" at La MaMa La Galleria.[2][21][22][23][24][25][26][27]

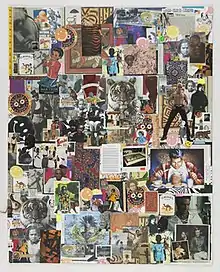

In 2019, Gordon Robichaux mounted a solo retrospective exhibition called "Happening".[2] The show included the then-current version of Weston's "Body Map" project, a collage begun in 2013, it was made from images and other small paper objects that he had, as one commenter said, "amassed over the last 30 years and cataloged in binders in different categories of race, gender, class issues, color, and other devices for organizing images".[28][29] "Body Map I" of 2015, shown here at right, contains images of prominent African-American men, including the face of Tom Morgan, the first openly gay president of the National Association of Black Journalists.[12]

In 2020, Weston received a $40,000 prize, the Roy Lichtenstein Award of the Foundation for Contemporary Arts.[1] That year he also showed "Blue Bedroom Blues" in an exhibition at the Ace Hotel Art Fair in New York and appeared in a groups show at the Parker Gallery ("A Page From My Intimate Journal II") and at the Tom of Finland Foundation, both in Los Angeles.[30][31][32]

Artistic style

My work is kind of crazy and it doesn't sell, but I think it definitely has an impact. I think when people look at it, it kind of registers.

Frederick Weston, Oral history interview conducted for the Archives of American Art in 2016[5]

Weston's exhibitions in non-traditional spaces did not usually attract reviews from critics in the mainstream press. Sponsoring organizations publicized the shows using websites or other online media and, for most of Weston's career, critical evaluations are rarely found.[4] Exceptions include a wall label written by the curator, John Neff, for the Art AIDS America traveling exhibition of 2016. He wrote, "Fredrick Weston’s tightly composed collages subject the leftovers of an HIV-positive person’s daily discipline of self-care—Q-Tip wrappers, Norvir (an HIV protease inhibitor) boxes and other pharmaceutical containers—to a severe formal order, transforming what would otherwise be wastepaper into abstract arrangements that rival the most accomplished paintings of the Modern movement. In this way, Weston’s collages transform evidence of a tedious and unwelcome habit—self-administration of the daily HIV-inhibiting ‘drug cocktail’—into decorative, pleasurable, life-affirming works of art".[33] A 2019 profile of Weston by Svetlana Kitto, written in conjunction with the "Happenings" exhibition, gives what is probably the fullest evaluation of his approach and its significance. She wrote, "Weston embraces collage for its immediacy as a fluid form of tactile poetry. Through his use of visual and textual alliteration, images and categories collide, cohere, rhyme, and fracture around a single color or cultural symbol, resisting synthesis or literal interpretation". His works, she wrote, express "range of ideas, rubrics, colors, vernaculars, histories, and ethics". She described his themes as, "the absurdity of labels, critique of racial categories and hierarchies, ecstasy of multiplicity, and the pleasure of being a person gifted with the language to celebrate, assess, and play within the world(s) we inhabit".[2] Other evaluations tended to locate Weston as a product of his environment, his sexual orientation, his race, and his affliction. One such, by Tessa Solomon, in ARTnews, said that Weston "interrogate[d] the intersections of Black culture and mass consumerism, as well as his own identity as a Black, queer, HIV-positive artist".[12]

Weston used binders to organize the source materials he used for his collages. He frequently used photocopiers to reproduce images that appealed to him and once said, "I multiply. I know I'm a multiplier... I love the copy machine".[5] His sources included items that he called trash as well as advertising and media reproductions involving AIDS, human bodies, and queer subjects.[2] Male fashions were a special concern of his. In 2020, he told an interviewer, "My whole practice really is about the way that men look, men comport themselves, and the way that men pose".[12] In 2019, a reviewer said that fashion was for Weston, "a pleasurable, expressive place of liberation where signifiers of race, gender, and class mix and match like paper dolls".[2]

Personal life

Weston possessed an outgoing and engaging personality and maintained close ties with family, friends he'd made while working in Detroit, and his fraternity brothers.[5] While living in New York, he suffered from poverty and drug abuse. He also endured emotional upheavals that would produce mental breakdowns. These problems resulted in frequent moves from one single-room-occupancy hotel to another and to frequent occasions during which his turmoil and loss of self-control would result in the loss of his possessions.[5]

For many years, Weston lived in SROs and hotels all over the city—the Esquire, the Senton, the Roger Williams, and the Breslin—where a series of financial and emotional upheavals would lead him, as a reporter said, to “lose everything three times.” [2] He later said that during breakdowns he would check himself into Bellevue Hospital for a few days to calm down. He also said that by 2001 he had given up use of LSD and cured himself of a crack addiction. In 2016, after he had turned his life around and his art career had begun to take hold, he addressed the massive challenges he had earlier faced. He said, "there used to be a time where things would happen and I would say, "Lord why me?" Now things happen to me and I'm like, "Why not me? I'm the man for the job. Why not me".[5]

In a 2019 interview, he explained his economic situation after he had received his AIDS diagnosis. He said, "When you get an AIDS diagnosis, in order to get your entitlements, you need to take a vow of poverty. In order to get housing and the health care that you need, you have to say you don’t have anything in your pockets, because the minute you start to have anything, they’re going to start taking things away from you. So I’ve just managed to learn, to live, and to seek out a rich life under those circumstances. I really consider going to my day treatment program, taking my medicine, keeping my viral load down and my T-cells up, kind of like my job".[3]

Weston was open about his sexual orientation but, at least on one occasion, rejected the label of gay man. In 2016, he said, "You can't put me on a cross for being a homosexual when really, I'm an asexual. I don't know why I have sex". Regarding the impact of AIDS on his art, he said, "There were the periods where I wasn't having sex just because I didn't want to catch it, or I didn't want to spread it, or didn't know how to spread it, or didn't want to get somebody else's strain. So my work really got to be a way of me using that energy".[5]

Weston's practice of collecting source materials for his collages could become an obsession. He joined and became an active member of Clutterers Anonymous to help cope with this problem.[5]

Weston died on October 21, 2020. Earlier that year, he had learned that he had advanced-stage bladder cancer and this proved to be the cause of his death. An obituary reported that he worried that treating the cancer might cause problems with the medications he took to control HIV. The obituary said, "he decided not to seek more hospital treatment, and he remained at home focusing on his art".[4]

Further reading

- DUETS: Frederick Weston & Samuel R. Delany in Conversation (Visual AIDS, 2021) ISBN 978-1-7326415-3-2[34]

Notes

- Visual AIDS created the Red Ribbon Project in 1991. It works to increase public awareness of AIDS through the visual arts, creating programs of exhibitions, events and publications, and partnerships with artists, galleries, museums, and AIDS organizations.[9]

- "Art AIDS America" contained 126 works. It was curated by Jonathan David Katz (State University of New York, Buffalo) and Rock Hushka (Chief Curator, Tacoma Art Museum) and it appeared in Bronx Museum of the Arts, the Tacoma Art Museum, the Alphawood Gallery in Chicago, the Bronx Museum of the Arts in New York, and two other locations.[17]

References

- "Frederick Weston". Foundation for Contemporary Arts. Retrieved November 27, 2020.

- "Frederick Weston at Gordon Robichaux". Art Viewer. July 26, 2019. Archived from the original on January 20, 2021. Retrieved November 27, 2020.

- "Meet a Member: Frederick Weston". Senior Planet. August 26, 2019. Archived from the original on December 3, 2020. Retrieved December 7, 2020.

- Alex Vadukul (November 20, 2020). "Frederick Weston, Outsider Artist Who Was Finally Let In, Dies at 73". New York Times. New York, N.Y. p. A24.

- "Oral history interview with Frederick Weston, 2016 August 31-September 5". Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on September 29, 2020. Retrieved November 29, 2020.

- "Frederick Weston" (PDF). Ortuzar Projects. Archived from the original on March 16, 2021. Retrieved November 30, 2020.

- "A Gallery of Art by HIV-Positive African Americans". The Body, a Visual AIDS website. April 16, 2008. Archived from the original on October 25, 2020. Retrieved December 4, 2020.

- "Who We Are". Village Care. Archived from the original on January 17, 2021. Retrieved December 4, 2020.

- Jared McCallister (November 30, 2003). "Raising Awareness About AIDS". New York Daily News. New York, N.Y. p. 2. Archived from the original on December 17, 2020. Retrieved December 11, 2020.

- Samuel R. Delany (April 1999). Times Square Red, Times Square Blue. NYU Press. p. 93. ISBN 978-0-8147-1920-6.

- Svetlana Kitto (May 17, 2019). "My First Time Attending the Last Address Tribute Walk for AIDS". Hyperallergic. Archived from the original on November 26, 2020. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- Tessa Solomon (November 27, 2020). "Frederick Weston, New York Artist Known for Incisive Collages, Has Died at 73". ARTnews. Archived from the original on December 11, 2020. Retrieved November 27, 2020.

- "Go Figure". Visual AIDS. Archived from the original on January 21, 2021. Retrieved November 30, 2020.

- "For Colored Boys Who Have Considered Suicide When All You Ever Needed Was the Blues" (PDF). Rankin Art Gallery, Ferris State University. Retrieved December 1, 2020.

- "'Mixed Messages': 'A(I)DS, Art + Words'". New York Times. New York, N.Y. June 23, 2011. p. C29.

- "Re/Presenting HIV/AIDS + International AIDS Posters". Davidson College Art Galleries. Retrieved November 30, 2020.

- "Art AIDS America Exhibition on View at the Bronx Museum of the Arts Summer 2016" (PDF). The Bronx Museum of the Arts. Retrieved November 30, 2020.

- "Persons of Interest". Visual AIDS. Archived from the original on January 16, 2021. Retrieved November 29, 2020.

- Holland Cotter (August 23, 2017). "Art Once Shunned, Now Celebrated in "Found: Queer Archaeology; Queer Abstraction"". New York Times. New York, N.Y. p. 9. Archived from the original on December 17, 2020. Retrieved December 11, 2020.

- "Cut Here: Matt Keegan, Siobhan Liddell, Frederick Weston". Gordon Robichaux Gallery. Archived from the original on October 31, 2020. Retrieved November 29, 2020.

- "Art & Design Events, New York, Thursday, 29 March 2018". Documents on Art & Design. March 29, 2018. Archived from the original on March 16, 2021. Retrieved November 29, 2020.

- "Gordon Robichaux 41 Union Square West #925 readings: Wayne Koestenbaum, Darinka Novitovic, and Frederick Weston". Documents on Art and Design. March 4, 2018. Retrieved November 29, 2020.

- "Proposals on Queer Play and the Ways Forward". Wall Street International Magazine. June 6, 2018. Archived from the original on January 21, 2021. Retrieved November 29, 2020.

- "Visual Arts and the AIDS Epidemic Symposium". Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. May 29, 2018. Archived from the original on October 28, 2020. Retrieved November 29, 2020.

- "A Page from My Intimate Journal (Part 1)". Gordon Robichaux Gallery. Archived from the original on October 31, 2020. Retrieved November 28, 2020.

- "Leslie-Lohman 127B Prince St reception: Queer Artist Fellowship: Alternate Routes". Documents on Art & Design: June 2018. Archived from the original on November 3, 2020. Retrieved November 29, 2020.

- "Inside, Out Here". La Mama La Galleria. Archived from the original on November 7, 2020. Retrieved November 28, 2020.

- Andy Battaglia (March 5, 2020). "Independent Art Fair Sales: The 2020 Edition Has a Soothing Opening". ARTnews. Archived from the original on January 20, 2021. Retrieved December 6, 2020.

- "Frederick Weston". Visual AIDS. Archived from the original on December 11, 2020. Retrieved November 30, 2020.

- "Program at The Ace Hotel; Frederick Weston: Blue Bedroom Blues". Outsider Art Fair. Archived from the original on September 26, 2020. Retrieved November 29, 2020.

- "What to See Right Now in New York Art Galleries: Art Reviews". New York Times. New York, N.Y. January 24, 2020. p. C22.

- ""Heaven and Hell" - Tom of Finland Foundation". Tom of Finland Foundation. Archived from the original on November 27, 2020. Retrieved December 6, 2020.

- John Neff. "Blue Bathroom Blues Set for Frederick Weston". Visual AIDS. Archived from the original on November 29, 2020. Retrieved November 30, 2020.

- "Art, Sex and Times Square". POZ. June 28, 2021. Retrieved June 30, 2021.

External links

- "Blue Bathroom Blues" performance, 2001

- "Share Your Vision" presentation, 2003

- "Metaphors and Their Distemper", 2015

- "Persons of Interest" exhibit, 2016

- Tribute to Affrekka Jefferson, 2016

- "AIDS at Home" presentation, 2017

- AIDS at Home: Art and Everyday Activism, 2017

- "Fag, Stag, or Drag?", 2018

- Discussion of "Alternate Endings, Activist Risings", 2018

- "Happening" exhibition, 2019

- "Frederick Weston Reads Intimidated For James Baldwin" poetry reading

- "Last Address Tribute Walk: Times Square"

- Visual AIDS conversation with Alivin Baltrop, Raynes Birkbeck, and Reverend Joyce McDonald, 2020

- "Page From My Intimate Journal" exhibition, 2020