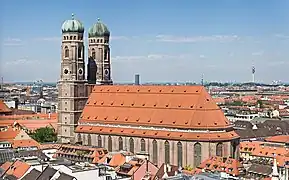

Frauenkirche, Munich

The Frauenkirche (Full name: German: Dom zu Unserer Lieben Frau, Bavarian: Dom zu Unsra Liabm Frau, lit. 'Cathedral of Our Dear Lady') is a church in Munich, Bavaria, Germany, that serves as the cathedral of the Archdiocese of Munich and Freising and seat of its Archbishop. It is a landmark and is considered a symbol of the Bavarian capital city. Although called "Münchner Dom" (Munich Cathedral) on its website and URL, the church is referred to as "Frauenkirche" by locals.

| Frauenkirche | |

|---|---|

| Dom zu Unserer Lieben Frau | |

| English: Cathedral of Our Lady | |

Bavarian: Dom zu Unsra Liabm Frau | |

| |

| 48°8′19″N 11°34′26″E | |

| Location | Frauenplatz 12 Munich, Bavaria |

| Country | Germany |

| Denomination | Roman Catholic |

| Website | www |

| History | |

| Status | Co-cathedral |

| Consecrated | 1494 |

| Architecture | |

| Functional status | Active |

| Architect(s) | Jörg von Halsbach |

| Architectural type | Cathedral |

| Style | Gothic Renaissance (domes) |

| Years built | preced. 12th century actual 1468–1488 |

| Completed | 1524 (domes added) |

| Specifications | |

| Length | 109 metres (358 ft) |

| Width | 40 metres (130 ft) |

| Administration | |

| Archdiocese | Munich and Freising |

| Clergy | |

| Archbishop | Reinhard Cardinal Marx |

| Priest(s) | Msgr. Klaus Peter Franzl |

| Laity | |

| Director of music | Lucia Hilz (Domkapellmeisterin) |

| Organist(s) | Ruben Sturm Martin Welzel (Assistant Organist, 2013–2021, and Associate Organist, 2021–2022) Msgr. Hans Leitner (2003–2021) |

Because of local height limits, the church towers are widely visible. As a result of the narrow outcome of a local plebiscite, city administration prohibits buildings with a height exceeding 99 m in the city center. Since November 2004, this prohibition has been provisionally extended outward, and consequently, no buildings may be built in the city over the aforementioned height. The south tower, which is normally open to those wishing to climb the stairs, will offer a unique view of Munich and the nearby Alps after its current renovation is completed.[1]

History

A late Romanesque church was added next to the town's first ring of walls in the 12th century,. This new church served as a second city parish following the older, Alter Peter church. The late Gothic cathedral visible today, which replaced the Romanesque church, was commissioned by Duke Sigismund and the people of Munich, and built in the 15th century.

The cathedral was erected in only 20 years' time by Jörg von Halsbach. Because there was not a nearby stone quarry and for other financial reasons, brick was chosen as building material. Construction began in 1468,[2] and when the cash resources were exhausted in 1479, Pope Sixtus IV granted an indulgence.

The two towers, which are both just over 98 meters (323 feet) tall, were completed in 1488, and the church was consecrated in 1494. There were plans for tall, open-work spires typical of the Gothic style, but given the financial difficulties of the time, the plans could not be realized. The towers remained unfinished until 1525.

German historian, Hartmann Schedel, printed a view of Munich including the unfinished towers in his famous Nuremberg Chronicle, also known as Schedel's World Chronicle. Finally, because rainwater was regularly penetrating the temporary roofing in the tower's ceilings, the towers were completed in 1525, albeit using a more budget-friendly design. This new design was modelled after the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem, which itself was modelled from late Byzantine architecture and erroneously considered to be Solomon's original temple.[3] The resulting domes atop each tower contributed to making the church a distinctive Munich landmark.

The building has a volume of about 200,000 m³,[4] and originally had the capacity to house 20,000 standing people. Later, pews for ordinary people were introduced. Considering late fifteenth-century Munich had only 13,000 inhabitants and an already established parish church in Alter Peter, it is quite remarkable that a second church of this magnitude was erected in the city.

In 1919, Eugen Leviné, leader of a short-lived Bavarian Socialist Republic, had the Frauenkirche declared a "revolutionary temple."[5]

The cathedral suffered severe damage during the later stages of World War II. After Allied forces' air raids, the church roof collapsed, one of the towers suffered severe damage, and the majority of the church's irreplaceable historical artifacts held inside were lost—either destroyed by bomb raids themselves, or removed with the debris in the aftermath. A multi-stage restoration effort began soon after the war. The final stage of restoration was completed in 1994.[6]

Architecture

The Frauenkirche was constructed from red brick in the late Gothic style within only 20 years. The building is designed very plainly, without rich Gothic ornamentation and with its buttresses moved into and hidden in the interior. This, together with the two towers' special design (battered upwards, etc.), makes the construction, mighty anyway, look even more enormous and gives it a near-modern appearance according to the principle of "less is more".

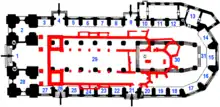

The Late Gothic brick building with chapels surrounding the apse is 109 metres (358 ft) long, 40 metres (130 ft) wide, and 37 metres (121 ft) high. Contrary to a widespread legend that says the two towers with their characteristic domes are exactly one meter different in height, they are almost equal: the north tower is 98.57 metres (323.4 ft) while the south tower is only 98.45 metres (323.0 ft), 12 centimetres (4.7 in) less. The original design called for pointed spires to top the towers, much like Cologne Cathedral, but those were never built because of lack of money. Instead, the two domes were constructed during the Renaissance and do not match the architectural style of the building, however they have become a distinctive landmark of Munich. With an enclosed space of about 200,000 m³, with 150,000 m³ up to the height of the vault, it is the second among the largest hall churches in general and the second among the largest brick churches north of the Alps (after St. Mary's Church in Gdańsk).[7]

In accordance with a law passed in 2004, no buildings within Munich city limits may be built taller than the Frauenkirche towers.[8]

Interior

Catholic Mass is held regularly in the cathedral, which still serves as a parish church.

It is among the largest hall churches in southern Germany. The hall is divided into 3 sectors (the main nave and two side aisles of equal height (31 metres (102 ft)) by a double row of 22 pillars (11 at either side, 22 metres (72 ft)) that help enclose the space. These are voluminous, but appear quite slim because of their impressive height and the building's height-to-width ratio. The arches were designed by Heinrich von Straubing.

From the main portal the view seems to be only the rows of columns with no windows and translucent "walls" between the vaults through which the light seems to shine. The spatial effect of the church is connected with a legend about a footprint in a square tile at the entrance to the nave, the so-called "devil's footstep".

A rich collection of 14th to 18th century artwork of notable artists like Peter Candid, Erasmus Grasser, Jan Polack, Hans Leinberger, Hans Krumpper and Ignaz Günther decorates the interior of the cathedral again since the last restoration.[9] The Gothic nave, several of the Gothic stained-glass windows, some of them made for the previous church, and the tomb monument of Louis IV, Holy Roman Emperor are major attractions. For the daily choral prayers Erasmus Grasser created in 1495–1502 the choir stalls with busts of apostles and prophets and small statues which survived the alterations of the Baroque period and the Gothic Revival, but burned in World War II, only the figures had been relocated and preserved. Therefore, the Frauenkirche still has the largest surviving ensemble of characters from the Late Gothic in Germany. The optical end of the sanctuary is formed by a column on which stands the St. Mary statue by Roman Anton Boos, which he executed in 1780 for the sounding board of the former pulpit. The former high altar painting completed by Peter Candid in 1620 has been moved to the north wall entrance of the sacristy and depicts the Assumption of Mary into heaven.

Teufelstritt, or Devil's Footstep and perpetual wind

Much of the interior was destroyed during World War II. An attraction that survived is the Teufelstritt, or Devil's Footstep, at the entrance. This is a black mark resembling a footprint, which according to legend was where the devil stood when he curiously regarded and ridiculed the 'windowless' church that Halsbach had built. (In baroque times the high altar obscured the one window at the very end of the church, that visitors can see now when standing in the entrance hall.)

In another version of the legend, the devil made a deal with the builder to finance construction of the church on the condition that it contain no windows. The clever builder, however, tricked the devil by positioning columns so that the windows were not visible from the spot where the devil stood in the foyer. When the devil discovered that he had been tricked, he could not enter the already consecrated church. The devil could only stand in the foyer and stomp his foot furiously, which left the dark footprint that remains visible in the church's entrance today.

Legend also says the devil then rushed outside and manifested his evil spirit in the wind that furiously rages around the church.[10]

Another version of that part of the legend has it that the devil came riding on the wind to see the church under construction. Having completely lost his temper, he stormed away, forgetting the wind, which will continue to blow around the church until the day the devil comes back to reclaim it.

Burials

The crypt contains the tombs of the Archbishops of Munich and Freising and among others of these members of the Wittelsbach dynasty:

- Louis IV, Holy Roman Emperor, (reg. 1294–1347)

- Duke Louis V, (reg. 1347–1361)

- Duke Stephen II, (reg. 1347–1375)

- Duke John II, (reg. 1375–1397)

- Duke Ernest, (reg. 1397–1438)

- Duke William III, (reg. 1397–1435)

- Duke Adolf, (reg. 1435–1441)

- Duke Sigismund, (reg. 1460–1467)

- Duke Albert IV, (reg. 1467–1508)

- Duke William IV, (reg. 1508–1550)

- Duke Albert V, (reg. 1550–1579)

- King Ludwig III, (reg. 1912–1918)

Organs

The current organs were built in 1993–1994 by Georg Jann. The Great Organ (1994)[11] on the west gallery has 95 stops (140 ranks, 7,165 pipes), which can be played from two four-manual general consoles (a tracker console behind the Rückpositiv division, and a second movable electric console on the lower choir gallery). The Choir Organ (1993)[12] is located on a gallery in the right nave, near the altar stairs. It has 36 stops (53 ranks) and can be played from a three-manual tracker console, as well as from the two main consoles on the west gallery. Both organs together contain 131 stops (193 ranks, 9,833 pipes) and are the largest organ ensemble in Munich.[13]

Organists

- Abraham Wißreiter, from 1576 to 1618[14]

- Hans Lebenhauser, from 1618 to 1634

- Anton Reidax, from 1634 to 1676

- Johann Kherner, from 1676 to 1699

- Johann Prunner, from 1699 to 1713

- Max Weißenböck, from 1713 to 1728

- Joseph Mamertus Falter, from 1728 to 1784

- Franz Anton Stadler, from 1792 to 1846

- Cajetan Stadler, from 1846 to 1899

- Karl Ludwig Ziegler, from 1899 to 1901

- Joseph Schmid, from 1901 to 1944

- Heinrich Wismeyer, from 1945 to 1969

- Franz Lehrndorfer, from 1959 to 2002

- Willibald Guggenmos, from 2001 to 2004 (Assistant Organist)

- Michael Hartmann, from 2002 to 2003 (Interim Organist)

- Msgr. Hans Leitner, from 2003 to 2021

- Martin Welzel, from 2013 to 2022 (Assistant Organist 2013–2021; Associate Organist 2021–2022)

- Ruben Sturm, since September 1, 2022

Bells

Both towers contain ten bells cast in the 14th, 15th, 17th and 21st centuries. Their combination is unique and incomparable in Europe. The heaviest bell called Susanna or Salveglocke is one of the biggest bells in Bavaria. It was cast in 1490 by Hans Ernst by order of Albrecht IV.[15]

| No. | Audio | Name | Cast in, by, at | Diameter (mm) | Mass (kg) | Note (Semitone-1/16) | Tower |

| 1 | Susanna (Salveglocke) | 1490, Hanns Ernst, Regensburg | 2.060 | ≈8.000 | a0 +3 | North | |

| 2 | Frauenglocke | 1617, Bartholomaeus Wengle, München | 1.665 | ≈3.000 | c1 +6 | North | |

| 3 | Bennoglocke | 1.475 | ≈2.100 | d1 +7 | South | ||

| 4 | Winklerin | 1451, Meister Paulus, München | 1.420 | ≈2.000 | e♭1 +15 | North | |

| 5 | Praesenzglocke | 1492, Ulrich von Rosen, München | 1.320 | ≈1.600 | e1 +9 | South | |

| 6 | Cantabona | 2003, Rudolf Perner, Passau | 1.080 | 870 | g1 +12 | South | |

| 7 | Frühmessglocke | 1442, Meister Paulus, München | 1.050 | ≈800 | a1 +10 | South | |

| 8 | Speciosa | 2003, Rudolf Perner, Passau | 890 | 540 | b1 +10 | South | |

| 9 | Michaelsglocke | 840 | 440 | c2 +12 | South | ||

| 10 | Klingl (Chorherrenglocke) | 14th century, anonymous | 740 | ≈350 | e♭2 +13 | South |

Other

In the church's north tower, since the mid-1980s, was a radio relay station of the German foreign intelligence service BND and another secret service . The relay station was removed in 2018 .

See also

References

- "Rising from Rubble 1945–1960". Munich Official City Portal. 2010. Retrieved 21 December 2010.

- "Cathedral to our lady". Munich-info. 2007. Archived from the original on 4 October 2010. Retrieved 21 December 2010.

- "Building History (in German)". Der Münchner Dom. 2006. Retrieved 21 December 2010.

- Calculation of the volume of the Frauenkirche (in German)

- Bronner, Stephen Eric (2012). Modernism at the Barricades: Aesthetics, Politics, Utopia. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 133. ISBN 978-023-115-822-0.

- "Munich churches:Frauenkirche". My Travel Munich. 2007. Retrieved 21 December 2010.

- Calculation of the volume (in German)

- "So schön ist Münchens Frauenkirche". muenchen.de (in German). Retrieved 18 October 2019.

- Das Hochaltarbild in die Munich Frauenkirche (in German)

- "Frauenkirche". Destination Munich. 2010. Retrieved 21 December 2010.

- Jann Opus 199, München, Liebfrauendom, Hauptorgel (in German). www.jannorgelbau.com. Retrieved February 1, 2018.

- Jann Opus 197, München, Liebfrauendom, Chororgel (in German). www.jannorgelbau.com. Retrieved February 1, 2018.

- Website of Hans Leitner, cathedral organist from 2003-2021 (in German) Archived 2019-04-13 at the Wayback Machine, with detailed information about the organs. Retrieved April 8, 2022.

- Leitner, Hans (2008), Die Orgeln der Münchner Frauenkirche und ihre Organisten, in Der Dom Zu Unserer Lieben Frau in München, ed. Peter Pfister. Regensburg: Schnell & Steiner, 69-73.

- Sigrid Thurm (1959), "Ernst, Hans", Neue Deutsche Biographie (in German), vol. 4, Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, p. 628; (full text online)