Franklin Knight Lane

Franklin Knight Lane (July 15, 1864 – May 18, 1921) was an American progressive politician from California. A member of the Democratic Party, he served as United States Secretary of the Interior from 1913 to 1920. He also served as a commissioner of the Interstate Commerce Commission, and was the Democratic nominee for Governor of California in 1902, losing a narrow race in what was then a heavily Republican state.

Franklin Lane | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| 26th United States Secretary of the Interior | |

| In office March 6, 1913 – March 1, 1920 | |

| President | Woodrow Wilson |

| Preceded by | Walter L. Fisher |

| Succeeded by | John Payne |

| Chair of the Interstate Commerce Commission | |

| In office January 13, 1913 – March 5, 1913 | |

| Preceded by | Charles A. Prouty |

| Succeeded by | Edgar E. Clark |

| Commissioner of the Interstate Commerce Commission | |

| In office July 2, 1906 – March 5, 1913 | |

| Preceded by | Joseph W. Fifer |

| Succeeded by | John Marble |

| City Attorney of San Francisco | |

| In office January 1, 1899 – January 1, 1902 | |

| Preceded by | Harry T. Creswell |

| Succeeded by | Percy V. Long |

| Personal details | |

| Born | July 15, 1864 DeSable, Prince Edward Island (now Canada) |

| Died | May 18, 1921 (aged 56) Rochester, Minnesota, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse | Anne Wintermute |

| Education | University of California, Berkeley University of California, Hastings |

| Signature |  |

Lane was born July 15, 1864, near Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island, in what was then a British colony but is now part of Canada, and in 1871, his family moved to California. After attending the University of California while working part-time as a reporter, Lane became a New York correspondent for the San Francisco Chronicle, and later became editor and part owner of a newspaper. Elected City Attorney of San Francisco in 1898, a post he held for five years, Lane ran in 1902 for governor and in 1903 for mayor of San Francisco, losing both races. In 1903, he received the support of the Democratic minority in the California State Legislature during the legislature's vote to elect a United States Senator from California.

Appointed a commissioner of the Interstate Commerce Commission by U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt in 1905 and confirmed by the Senate the following year, Lane was reappointed in 1909 by President William Howard Taft. His fellow commissioners elected him as chairman in January 1913. The following month, Lane accepted President-elect Woodrow Wilson's nomination to become Secretary of the Interior, a position in which he served almost seven years until his resignation in early 1920. Lane's record on conservation was mixed: he supported the controversial Hetch Hetchy Reservoir project in Yosemite National Park, which flooded a valley esteemed by many conservationists, but also presided over the establishment of the National Park Service.

The former Secretary died of heart disease at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, on May 18, 1921. Because of two decades of poorly paid government service, and the expenses of his final illness, he left no estate, and a public fund was established to support his widow. Newspapers reported that had he not been born in what is now Canada, he would have become president. In spite of that limitation, Lane was offered support for the Democratic nomination for vice president, though he was constitutionally ineligible for that office as well.

Early life

Lane was born in DeSable, west of Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island, on July 15, 1864, the first of four children of Christopher Lane and the former Caroline Burns.[1][2] Christopher Lane was a preacher who owned a farm outside Charlottetown; when his voice began to fail, he became a dentist.[3] The elder Lane, disliking the island colony's cold climate, moved with his family to Napa, California in 1871,[4] and to Oakland in 1876, where Franklin graduated from Oakland High School.[2] Franklin Lane was hired to work in the printing office of the Oakland Times, then worked as a reporter, and in 1884 campaigned for the Prohibition Party.[5] From 1884 to 1886, he attended the University of California at Berkeley, though he did not graduate.[2] Lane later wrote, "I put myself through college by working on vacation and after hours, and I am very glad I did it."[6] He later received honorary Doctor of Laws degrees from the University of California, from New York University, Brown University, and the University of North Carolina.[7] After leaving college, he worked as a reporter for the San Francisco Chronicle.[1] In 1889,[8] he was admitted to the California Bar, having attended Hastings Law School.[2]

Rather than practicing law, Lane moved to New York City to continue his newspaper career as a correspondent for the Chronicle. There he became a protégé of the reformer Henry George and a member of New York's Reform Club.[9] He returned to the West Coast in 1891 as editor and part owner of the Tacoma News. He was successful in driving a corrupt chief of police into exile in Alaska, but the business venture as a whole was unsuccessful, and the paper declared bankruptcy in 1894,[10] a victim of the poor economy and Lane's espousal of Democratic and Populist Party causes. In 1893, Lane married Anne Wintermute; they had two children, Franklin Knight Lane, Jr. and Nancy Lane Kauffman.[2]

Lane moved back to California in late 1894, and began to practice law in San Francisco with his brother George. He also wrote for Arthur McEwen's Letter, a newspaper which crusaded against corruption, especially in the San Francisco Bay area and in the Southern Pacific Railroad.[11] In 1897–98, he served on the Committee of One Hundred, a group which was tasked with drafting a new city charter.[2] The charter required the city to own its own water supply.[12]

California politician

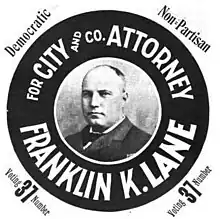

In 1898, Lane, running as a Democrat, was elected to the combined position of City and County Attorney, defeating California's sitting Attorney General, W. F. Fitzgerald,[13] by 832 votes in a year that otherwise saw most offices across the state fall to the Republicans.[9] He was re-elected in 1899 and 1901.[14]

Lane ran for Governor of California in 1902 on the Democratic and Non-Partisan tickets.[2] At a time when California was dominated by the Republican Party, he lost by less than a percentage point to George Pardee. (Theodore Roosevelt won the state by 35 points two years later.)[15] Between 8,000 and 10,000 votes were disqualified on various technicalities, possibly costing him the election.[16] During the campaign, the influential San Francisco Examiner slanted its news coverage against him. Examiner owner William Randolph Hearst later denied responsibility for this policy, and stated that if Lane ever needed anything, he should send Hearst a telegram. Lane retorted that if Hearst received a telegram purportedly signed by Lane, asking him to do anything, he could be sure it was a forgery.[13]

Journalist Grant Wallace wrote of Lane at the time of the gubernatorial campaign:

That Lane is a man of earnestness and vigorous action is shown in ... every movement. You sit down to chat with him in his office. As he grows interested in the subject, he kicks his chair back, thrusts his hands way to the elbows in his trouser pockets and strides up and down the room. With deepening interest he speaks more rapidly and forcibly, and charges back and forth across the carpet with the heavy tread of a grenadier.[17]

At the time, the state legislatures still elected United States Senators, and in 1903, Lane received the vote of the state legislature's Democratic minority in the Senate election.[8] However, the majority Republicans backed incumbent George Clement Perkins, who was duly re-elected. Later that year, City Attorney Lane ran for mayor of San Francisco, but again was defeated, finishing third in the race.[9] He returned to the private practice of law,[9] and would not again stand for elective office.[11]

Even before the mayoral election, there was support for Lane as a potential Democratic candidate for vice president, though since he was born in what was by then a Canadian province he was ineligible under the Twelfth Amendment to the United States Constitution. In an era when political convention delegates were far more free to make their own choices than they are today, Lane wrote that he had heard that he could gain the support of the New York delegation, which he declined to do.[13] While returning to California from a trip to Washington, D.C., as an advocate for the Hetch Hetchy Reservoir project, he stopped in Austin, Texas, to confer with Democratic leaders and address the legislature.[18] The New York Times saw this as part of a campaign to secure the vice-presidential nomination, and stated that he had been promised help from Texas.[19]

Interstate Commerce Commission

Appointment and confirmation

The railroad companies, which were loosely regulated by the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC), exercised great power in California because of the lack of alternate means of shipping freight. Lane had taken cases against those corporations in his law practice, and, in his gubernatorial campaign, had argued that they had too much power. In early 1904, Benjamin Wheeler, president of the University of California, suggested to President Roosevelt that Lane would be an admirable choice to serve on the ICC. Roosevelt agreed, and promised to name him to the next ICC vacancy. When that vacancy occurred in early 1905, Roosevelt forgot his promise and instead named retiring five-term Senator Francis Cockrell of Missouri. Wheeler wrote to remind Roosevelt that he had said he would name Lane.[20] Roosevelt apologized for his oversight, but noted that, as he had just been re-elected, "I shall make ample amends to Lane later".[20]

In December 1905, Commissioner Joseph W. Fifer resigned from the ICC and on December 6, 1905, President Roosevelt named Lane to fill the remaining four years in his term.[21][22] Opposition to the appointment came from Republicans, who pointed out that were the nominee to be confirmed by the Senate, three of the five commissioners would be from the minority Democratic Party.[20] Historian Bill G. Reid, in his journal article about Lane, suggests that Lane's liberal record was a factor in the Senate's hesitation to confirm him.[11] The dispute held up Senate approval. However, Republican Congressman William Peters Hepburn proposed legislation which, though its primary purpose was increased railroad regulation, would expand the Commission by two members. Roosevelt indicated that he would appoint Republicans to the new positions, and opposition to Lane's nomination dissipated. The resultant Hepburn Act was signed by President Roosevelt on June 29, 1906, while his nominee was confirmed the same day and was sworn in on July 2, 1906.[23]

The City of San Francisco suffered a severe earthquake on April 18, 1906. Lane, who was living in north Berkeley while awaiting Senate confirmation, hurried to the city within hours of the earthquake to do what he could to help. Mayor Eugene E. Schmitz immediately appointed him to the Committee of Fifty to deal with the devastation of the earthquake and subsequent fire, and plan the rebuilding of the city. According to Lane's friend, writer Will Irwin, Lane did not content himself with committee work, but personally fought the fire, helping to save much of the Western Addition. In late April, the commissioner-designate took the train east to Washington, where he unsuccessfully fought to obtain Federal money to help the city's recovery.[24]

Commission work

The new commissioner spent the second half of 1906 attending ICC hearings around the country. The Hepburn Act had given the Commission broad powers over the railroads, and the Commission worked to deal not only with past railroad abuses, but to strike a balance between the desires of railroads and those of shippers.[25]

There was a severe shortage of coal in the Upper Midwest in late 1906, especially in North Dakota, and President Roosevelt ordered an investigation. Railroad companies were accused of failing to send cars with coal to that region that could then be used to transport grain from that region to Great Lakes ports. It was alleged the companies were waiting for the lakes to freeze over before sending cars so that the grain would have to be transported by rail all the way to market instead of by water transport. Lane led the inquiry and held hearings in Chicago, and concluded that the car shortage was due to demand for cars further west, and that it would actually cause area railways to lose money since they could not transport the grain to port.[26] In January 1907, he submitted his report to Roosevelt, which set out the causes of the shortage. He found that fifty million bushels of grain still remained on North Dakota farms or in the state's grain elevators, because of lack of space in eastbound railroad cars. He recommended that railroad companies pool their cars with neighboring lines.[27]

The Commission spent much of 1907 investigating the railroads and other companies owned by Edward H. Harriman, holding hearings across the country. In October, Lane determined that the Southern Pacific Railroad, one of Harriman's lines, was engaged in rebating, a practice of effectively giving special rates to favored shippers that had been outlawed by the Hepburn Act.[28]

Lane was reappointed as commissioner by President William Howard Taft on December 7, 1909, this time to a full seven-year term, and was confirmed by the Senate three days later.[22] He was also approached by, as he put it, "a good many people" who urged him to seek the Democratic nomination for Governor of California in 1910.[29] He did not run, remaining an ICC commissioner.[29] Taft designated Lane as a U.S. delegate to the 1910 International Railways Congress.[30] The Congress, which convened every five years, met in Berne, Switzerland. Before adjourning in anticipation of meeting in 1915 in Berlin, it elected Lane to its Permanent International Commission.[31]

On July 1, 1911, the ICC ordered a "sweeping investigation" into the activities of express companies, which transported and delivered parcels.[32] Lane presided over a lengthy hearing in New York in November 1911.[33] Fellow Commissioner James S. Harlan noted that after hearing of the abuses of the express system, Lane recommended to Congress that it establish a parcel post service as part of the United States Post Office Department.[34] Parcel post began on January 1, 1913, and was an immediate success.[35]

Early in 1912, Commissioner Lane returned to New York to preside over hearings (begun on the Commission's own initiative) into oil pipelines. While investigating the sale of pipelines to the Standard Oil Company, he grew frustrated with the testimony of a witness who, though secretary of several pipeline companies, could not say who authorized the sales. "I don't want to deal with a clerk or one of your $5,000 a year men. I want testimony from someone who can speak with authority."[36] The Commission held that oil pipelines were common carriers, and ordered the companies owning them to file rate schedules and otherwise comply with the Interstate Commerce Act.[37]

Lane also gave attention to improving the ICC's internal capabilities. Lane and his ally, fellow Commissioner Balthasar H. Meyer, supported increasing the Commission's ability to compute marginal rates, and the Commission engaged noted economist Max O. Lorenz (inventor of the Lorenz curve) for this task.[38] Lane also advocated the creation of a new commission with powers over any corporation engaged in interstate commerce, as the best way to prevent trusts.[7]

Secretary of the Interior

Selection by Wilson

.jpg.webp)

In the 1912 presidential election, Lane supported Democratic candidate and New Jersey Governor Woodrow Wilson, though he declined to make campaign speeches on Wilson's behalf, citing ICC policy that commissioners act in a nonpartisan manner.[39] Wilson was elected on November 5, 1912, and on November 21 the commissioner spent much of the day with Colonel Edward M. House, the President-elect's advisor, who would play a key role in selecting Cabinet appointees. The possibility of Lane becoming Secretary of the Interior was discussed, but he indicated he was happy in his present position.[40] After the meeting, Lane had second thoughts, and asked House if he would have a free hand as Interior Secretary. House indicated that were he to prove capable in the position, Wilson would not interfere. Colonel House did not immediately recommend Lane for the job, but went on to consider other candidates, such as former San Francisco mayor James D. Phelan and Wilson friend Walter Page.[40]

At the ICC meeting on January 8, 1913, the commissioners elected Lane as the new chairman, effective January 13.[41] Wilson continued to keep his Cabinet intentions quiet, and Lane noted in January 1913 of those who met with the President-elect in New Jersey, "nobody comes back from Trenton knowing anything more than when he went".[42] On February 16, House met again with him (on Wilson's instructions) to get a better sense of the ICC chairman's views on conservation.[40] According to House's diaries, Lane, while reluctant to leave his position as chairman, was willing to serve in the Interior position if offered. He considered the position the most difficult Cabinet post but was also willing to serve in any other capacity.[43]

As Wilson adjusted his lineup of potential Cabinet appointees, he and House considered Lane for the positions of Attorney General and Secretary of War.[43] Finally, Wilson wrote to him on February 24, 1913, offering him the Interior position,[40] and, although the two had never met, he accepted the post.[44] According to The New York Times, Chairman Lane was selected since he was one of the few California Democrats who had fought the railroads and who was not beholden to Hearst.[45] At the time, it was customary not to make an official announcement of Cabinet appointments until the new president formally submitted the names to the Senate on the afternoon of Inauguration Day, March 4; however, The New York Times obtained the list of Wilson's appointees a day early.[46] The Senate met in special session on March 5, and approved all of President Wilson's Cabinet appointees.[47]

Department activities

The Department of the Interior in 1913 was a hodgepodge of different agencies. Many of them, such as the Pensions Office, Indian Office, and General Land Office had been departmental responsibilities since the Interior Department was organized in 1849. Others, such as the Bureau of Education, the Geological Survey and the Bureau of Mines, had been added later.[48] The Department was also responsible for national parks, the Patent Office, the United States Capitol building and grounds, Howard University, Gallaudet University, St. Elizabeths Hospital and the Maritime Canal Company of Nicaragua,[49] charged with building a canal upon which work had been suspended for twenty years.[50]

Soon after taking office in 1913, Lane became involved in the Hetch Hetchy Valley dispute. San Francisco had long sought to dam the Tuolumne River in Yosemite National Park to create a reservoir that would assure a steady flow of water to the city. Lane had supported the project as City Attorney and continued his advocacy as the new Interior Secretary.[51] The Hetch Hetchy project was strongly opposed by many conservationists, led by John Muir, who said, "Dam Hetch Hetchy! As well dam for water tanks the people's cathedrals and churches; for no holier temple has ever been consecrated by the heart of man."[51] In spite of Muir's objections, Lane was successful: Congress authorized the project after a long and bitter battle.[51]

The new Secretary sought allies in Congress to implement his agenda. One such ally was the new junior senator from Montana, Thomas J. Walsh, whose support was key to the passage of the Hetch Hetchy legislation. While Walsh dissented from Lane's policies on national parks, for example by supporting local control of development in his home state's Glacier National Park, he sided with him on subjects ranging from development of Alaska to reclamation projects.[52] The Interior Secretary advocated leasing, rather than selling, public lands with possible mineral deposits, and Senator Walsh pursued legislation in this area.[53] While the two were successful in providing for coal land leasing in Alaska, a general minerals leasing bill would not be passed until shortly after Lane left office in 1920.[54]

In July 1913, Lane left on a long inspection tour of National Parks, Indian reservations, and other areas under the Interior Department's jurisdiction. Fearful that local employees would control what he was allowed to see, he sent an assistant to visit each site and provide him with a complete report on it two weeks in advance of his arrival. The tour was interrupted in August, when President Wilson asked his Interior Secretary to go to Denver and serve as his representative at the Conference of Governors. Lane did, and then rejoined his inspection party in San Francisco. After several days of meetings there, he collapsed because of an attack of angina pectoris. After three weeks recuperating, he returned to Washington against medical advice to resume his work.[55] Following the death of Justice Horace Harmon Lurton, Lane was considered a possibility for elevation to the Supreme Court;[56] however, Wilson chose another member of his cabinet, James Clark McReynolds.

As Interior Secretary, Lane was responsible for the territories, and advocated the development of the Alaska Territory. While private railroads had been established there, they were not successful, and he pushed for a government-built railroad, which he believed would lead to large-scale population movement into Alaska.[57] In 1914, Congress passed a bill authorizing construction of the Alaska Railroad, which passed the Senate following a two-day speech in support by Walsh.[58] Lane was the first Interior Secretary to appoint an Alaska resident, John Franklin Alexander Strong, as territorial governor.[11] Secretary Lane's vision for the territory was, "Alaska should not, in my judgment, be regarded as a mere storehouse of materials on which the people of the States may draw. She has the potentialities of a State. And whatever policies may be adopted should look toward an Alaska of homes, of industries, and of an extended commerce."[59]

Despite his role in the Hetch Hetchy controversy, Lane was friendly towards the National Park movement, and in 1915 hired Stephen Mather to oversee the parks for which the Department was responsible.[51] Mather, a self-made millionaire and member of the Sierra Club, had written Lane a bitter letter in late 1914, complaining that the national parks were being exploited for private profit. Lane was intrigued by Mather's letter, made inquiry, and found that Mather was well thought of by Lane's friends—and had, like Lane, attended the University of California.[60] Mather's advocacy led to the establishment of the National Park Service in 1916.

In 1915, Lane returned to San Francisco to open the Panama-Pacific International Exposition. The President was supposed to open the fair, but was unable to attend, and sent the Interior Secretary in his place.[61] In 1916, Wilson appointed Lane to lead the American delegation and meet with the Mexican commissioners at Atlantic City, New Jersey about the unstable military situation in Mexico. These negotiations led to the withdrawal of United States troops from Mexico.[62]

The Interior Department had never had a central headquarters, but had worked from offices scattered across Washington, with the bulk of the department located in the old Patent Office building. The Secretary lobbied for a new building for the Department, and, after Congress appropriated the funds, construction went ahead and the building was opened in early 1917.[63] The structure, located at 1800 F Street N.W., now houses the General Services Administration.

Mather, who had been appointed the first director of the National Park Service, began to display apparent mental illness in 1917. His assistant, Horace Albright, reported this condition to Lane. The Secretary chose to keep Mather in his position, while allowing Albright to perform the functions of Mather's job until Mather recovered, keeping all of this secret.[64] According to Albright, Lane was not a conservationist, but did not care to interfere in the decisions of his officials, and so let Mather and Albright have free rein.[65] Lane wrote in 1917:

A wilderness, no matter how impressive and beautiful, does not satisfy this soul of mine, (if I have that kind of thing). It is a challenge to man. It says, 'Master me! Put me to use! Make me something more than I am.'[66]

World War I responsibilities

In 1916, Wilson appointed Lane to the Council of National Defense (CND), where he urged cooperation between the private and public sectors. He defused a difficult situation for the CND when it decided to merge its male-dominated state and local organizations with the separate Women's Committee into a unified Field Division. Lane headed the Division, leading a board of five men and five women.[21]

Lane bitterly opposed what he saw as the President's hesitation to commit the country to war. He wrote to his brother George in February 1917:

... in Mexico, Cuba, Costa Rica, and Europe we have trouble. The country is growing tired of delay, and without positive leadership is losing its keenness of conscience and becoming inured to insult. Our Ambassador in Berlin is held as a hostage for days—our Consuls' wives are stripped naked at the border, our ships are sunk, our people killed—and yet we wait and wait! What for I do not know. Germany is winning by her bluff, for she has our ships interned in our own harbors.[67]

Lane was a strong advocate of preparedness in the prelude to U.S. involvement in World War I. In early 1917, he urged Wilson to authorize the arming and convoying of merchant vessels. Wilson refused, but changed his mind when informed of the Zimmermann Telegram. In a critical Cabinet meeting in March 1917, Lane, with other Cabinet members, urged American intervention in the war.[21]

He helped Thomas Garrigue Masaryk to create Washington Declaration in October 1918. [68]

With Lane's support, the nation's railroads voluntarily united to form a Railroad War Board to meet the emergency. Lane made many effective speeches for the Committee on Public Information. The Secretary penned two brief works for the Committee, Why We Are Fighting Germany and The American Spirit, which were well received and widely distributed.[21] He urged businessmen to make "sacrifices as worthy as those of the men on their way to the trenches".[7] President Wilson reportedly stopped discussing matters of importance at Cabinet meetings because the "gregarious" Lane divulged confidential matters.[21]

Lane was a supporter of the Treaty of Versailles and of the League of Nations. He wrote articles urging, in vain, U.S. ratification of the treaty establishing the international organization.[62]

Later life and legacy

On December 17, 1919, Lane confirmed rumors that had been circulating in Washington for some months that he would be leaving the Cabinet. Secretary Lane stated that he had not done so earlier because of President Wilson's illness. While he gave no specific reason for his departure, The New York Times reported that Lane had found it difficult to make ends meet on a Cabinet officer's salary of $12,000 and desired to make more money for himself and his family.[69]

As Lane prepared to leave office in January 1920, he reflected on the postwar world:

But the whole world is skew-jee, awry, distorted and altogether perverse. The President is broken in body, and obstinate in spirit. Clemenceau is beaten for an office he did not want. Einstein has declared the law of gravitation outgrown and decadent. ... Oh God, I pray, give me peace and a quiet chop. I do not ask for power, nor for fame, nor yet for wealth.[70]

Lane resigned in February 1920, and left office on March 1. He subsequently accepted employment as vice president and legal advisor to the Mexican Petroleum Company, which was run by Edward Doheny (who, after Lane's death, would be implicated in the Teapot Dome scandal), as well as a directorship of the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company.[62]

In a letter to Democratic presidential candidate and Ohio Governor James M. Cox in July 1920, Lane set forth his vision for America:

We want our unused lands put to use. We want the farm made more attractive through better rural schools, more roads everywhere ... [W]e want more men with garden homes instead of tenement homes. We want our waters, that flow idly to the sea, put to use ... [W]e want fewer boys and girls, men and women, who cannot read or write the language of our laws, newspapers, and literature ... [T]he framing of our policies should not be left to emotional caprice, or the opportunism of any group of men, but should be result of sympathetic and deep studies by the wisest men we have, regardless of their politics ... [W]e want our soldiers and sailors to be more certain of our gratitude ... [W]e are to extend our activities into all parts of the world. Our trade is to grow as never before. Our people are to resume their old place as traders on the seven seas. We are to know other people better and make them all more and more our friends, working with them as mutually dependent factors in the growth of the world's life[71]

By early 1921, Lane's health was failing, and he sought treatment at the Mayo Clinic. He was able to leave the Clinic and spend the remainder of the winter in warmer areas as advised by his physicians, but soon returned. Lane's heart was in such poor condition that the Clinic could not give him general anesthesia during his heart operation. Lane survived the operation, and wrote of the ordeal, but died soon afterward.[62] According to his brother, George Lane, the former Secretary left no will or estate. The vice-president of Lane's company noted that the Californian had worked 21 years for the Government on a "living salary", and the earnings from the one year of substantial wages had been heavily sapped by illness.[7][62] Lane's body was cremated, and his ashes thrown to the winds from atop El Capitan peak in Yosemite National Park.[72]

According to newspapers reporting Lane's death, it was said that had he been born in the United States he would have been elected president.[7][62][73] Following Lane's death, a memorial committee was formed by Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover, former Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin D. Roosevelt and former Lane assistant and member of the Federal Reserve Board Adolph C. Miller. The committee established a Franklin K. Lane Memorial Fund, initially dedicated to the support of Lane's widow, Anne Lane, and upon her death to be used to promote causes in which her husband believed.[74] The two future presidents, Miller, and National Park Service Director Mather were among the major contributors to the fund.[9] In 1939, after Mrs. Lane's death, the corpus of the trust (just over $100,000) was transferred to the former Secretary's alma mater, the University of California, to promote the understanding and improvement of the American system of democratic government.[9] Fifty years later, the entrusted amount, still administered by the University, had grown to almost $1.9 million.[9]

In November 1921, Lane Peak in Mount Rainier National Park was named for the former Secretary.[75] Lane was named a National Historic Person on the advice of the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada on May 19, 1938.[76] A federal plaque was affixed to a cairn reflecting that honor near his DeSable, PEI, birthplace. Other tributes to Lane included a World War II Liberty ship, a New York City high school, and a California redwood grove.[9] Lane's patriotic essay "Makers of the Flag" adapted from a speech he delivered to Interior Department employees on Flag Day 1914, continues to be reprinted as a speech and in schoolbooks.[77][78]

References

- Abbott, Lawrence (1921), "A Passionate American", The Outlook, vol. 128, p. 205, retrieved 2009-01-27

- Lane 1922, pp. xxiii–xxiv.

- Lane 1922, p. 3.

- Lane 1922, p. 5.

- Lane 1922, p. 9.

- Lane 1922, p. 11.

- "Lane death mourned" (PDF), Los Angeles Times, 1921-05-19, retrieved 2009-03-27 (subscription required)

- The American Year Book, D. Appleton & Co., 1914, p. 163, retrieved 2009-01-27

- Franklin K. Lane, Institute of Governmental Studies, UC Berkeley, retrieved 2009-01-27

- Lane 1922, p. 28.

- Reid 1964, p. 450.

- Brechin 2006, p. 336.

- Page, Walter (April 1922), "Letters of a high-minded man, part I" (PDF), The World's Work, pp. 527–33, retrieved 2009-04-08

- Lane 1922, p. 50.

- Warren, Kenneth (2008), Encyclopedia of U.S. Campaigns, Elections, and Electoral Behavior, Sage Publications Inc., p. 70, ISBN 978-1-4129-5489-1, retrieved 2009-01-27

- Lane 1922, p. 22.

- Lane 1922, p. 4.

- Lane 1922, p. 42.

- "Would be Vice President" (PDF), The New York Times, 1903-04-11, retrieved 2009-01-27

- Page, Walter (April 1922), "Letters of a high-minded man, part II" (PDF), The World's Work, pp. 639–40, retrieved 2009-02-15

- Venzon 1999, p. 327.

- The Interstate Commerce Commission: the First Fifty Years, The George Washington University Law Review, 1938, pp. 625–627

- Lane 1922, pp. 61–62.

- Lane 1922, pp. 59–61.

- Lane 1922, pp. 63–64.

- "Lane defends railroads" (PDF), The New York Times, 1906-12-23, retrieved 2009-01-27

- "Car shortage costly" (PDF), The New York Times, January 3, 1907, retrieved 2015-06-10

- "Harrison road still rebating" (PDF), The New York Times, October 15, 1907, retrieved 2009-01-27

- Lane 1922, p. 70.

- Lane 1922, p. 75.

- "Railway congress ends" (PDF), The New York Times, July 17, 1910, retrieved 2009-01-27

- "Express companies must face inquiry" (PDF), The New York Times, 1911-07-02, retrieved 2009-02-20

- "Overcharging pays express companies" (PDF), The New York Times, 1911-11-26, retrieved 2009-01-27

- Lane 1922, pp. 100–01.

- Parcel post: delivery of dreams, Smithsonian Institution, retrieved 2009-02-05

- "Pipe lines under scrutiny" (PDF), The New York Times, 1912-01-25, retrieved 2009-01-27

- "Pipe lines common carriers" (PDF), The New York Times, 1912-06-14, retrieved 2009-04-15

- Miranti Jr., Paul J. (1990), "Measurement and organizational effectiveness: the ICC and accounting-based regulation, 1887–1940" (PDF), Business and Economic History, p. 189, retrieved 2009-02-20

- Lane 1922, p. 106.

- Righter 2006, p. 119.

- "Lane heads Commerce Commission" (PDF), The New York Times, 1913-01-09, retrieved 2009-01-27

- Lane 1922, p. 124.

- House, Edward; Seymour, Charles (1926), The intimate papers of Colonel House arranged as a narrative by Charles Seymour, Houghton Mifflin Co., pp. 107–08, retrieved 2009-02-19

- Righter 2006, pp. 118–19.

- "Cabinet's open door amazes old-timers" (PDF), The New York Times, 1913-03-16, retrieved 2009-02-13

- "Cabinet complete, Wilson announces" (PDF), The New York Times, 1913-03-04, retrieved 2009-01-27

- Shaw, Albert (April 1913), "Record of Current Events", Review of Reviews and World's Work, retrieved 2009-01-27

- Annual Report of the Secretary of the Interior, U.S. Government Printing Office, 1913, p. ii, retrieved 2009-02-12

- Annual Report of the Secretary of the Interior, U.S. Government Printing Office, 1913, pp. iv–vi, retrieved 2009-02-12

- Nicaragua Canal (1889–1983), globalsecurity.org, retrieved 2009-01-27

- Utley, Robert; Mackintosh, Barry (1989), The Department of Everything Else: Highlights of Interior History, U.S. Department of Interior, retrieved 2009-01-27

- Bates 1999, pp. 101–05.

- Middleton, James (April 1916), "A New West: The Attempts To Open Up The Natural Treasures Of The Western States", The World's Work: A History of Our Time, XXXI: 669–680, retrieved 2009-08-04

- Bates 1999, pp. 106–14.

- Lane 1922, pp. 139–40.

- ‘Democrat Likely to be Nominated in Lurton’s Place’; The Birmingham News, July 13, 1914, p. 7

- "Lane would open Alaska" (PDF), The New York Times, 1914-07-23, retrieved 2009-01-27

- Bates 1999, p. 105.

- "The government has big plans for developing Alaska" (PDF), The New York Times, 1914-03-22, retrieved 2009-01-27

- Albright 1999, pp. 30–32.

- Brechin 2006, p. 245.

- "Lane long in public life" (PDF), The New York Times, 1921-05-19, retrieved 2009-01-27

- Albright 1999, pp. 217–18.

- Albright 1999, pp. 200–02.

- Albright 1999, p. 335.

- Lane 1922, p. 258.

- Lane 1922, pp. 237.

- Preclík, Vratislav. Masaryk a legie (Masaryk and legions), váz. kniha, 219 str., vydalo nakladatelství Paris Karviná, Žižkova 2379 (734 01 Karvina, CZ) ve spolupráci s Masarykovým demokratickým hnutím (Masaryk Democratic Movement, Prague), 2019, ISBN 978-80-87173-47-3, pages 101-102, 124–125, 128, 129, 132, 140–148, 184–190.

- "Secretary Lane to quit the Cabinet" (PDF), The New York Times, 1919-12-18, retrieved 2009-01-27

- Lane 1922, p. 391.

- Lane 1922, pp. 346–49.

- "To scatter Lane's ashes" (PDF), The New York Times, 1921-05-20, retrieved 2009-01-27

- "Franklin K. Lane" (PDF), The Washington Post, 1921-05-19, retrieved 2009-04-17 (subscription required)

- "Public to aid Lane fund" (PDF), The New York Times, 1921-10-14, retrieved 2009-01-27

- "Named in Lane's memory" (PDF), The New York Times, 1921-11-05, retrieved 2009-01-27

- Franklin Knight Lane National Historic Person, Directory of Federal Heritage Designations, Parks Canada

- Grissom, Elwood (2008), Americanization, Bibliobazaar, p. 49, ISBN 978-0-554-77433-6, retrieved 2009-02-11

- O'Neill, James (2007), Modern Short Speeches — Ninety Eight Complete Examples, Read Books, p. 140, ISBN 978-1-4067-3843-8, retrieved 2009-02-11

Bibliography

Books

- Albright, Horace (1999), Creating the National Park Service, University of Oklahoma Press, ISBN 978-0-8061-3155-9

- Bates, James (1999), Senator Thomas J. Walsh of Montana, University of Illinois Press, ISBN 978-0-252-02470-2

- Brechin, Horace (2006), Imperial San Francisco, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-25008-6

- Lane, Franklin (1922), Lane, Anne; Wall, Louise (eds.), The Letters of Franklin K. Lane, Houghton Mifflin

- Righter, Robert (2006), The Battle over Hetch Hetchy, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-514947-0

- Venzon, Anne (1999), The United States in the First World War, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 978-0-8153-3353-1

Journals

External links

- Biographical vignette from the U.S. National Park Service

- The Department of Everything Else: Highlights of Interior History (1989)

- Works by Franklin Knight Lane at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Franklin Knight Lane at Internet Archive

- Works by Franklin Knight Lane at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Lane Peak