Fortifications of London

The fortifications of London are extensive and mostly well maintained, though many of the City of London's fortifications and defences were dismantled in the 17th and 18th century. Many of those that remain are tourist attractions, most notably the Tower of London.

History

Roman times

London's first defensive wall was built by the Romans around 200 AD. This was around 80 years after the construction of the city's fort (whose north and west walls were thickened and doubled in height to form part of the new city wall), and 150 years after the city was founded as Londinium.

The London Wall remained in active use as a fortification for over 1,000 years afterwards, defending London against raiding Saxons in 457 and surviving into Medieval times. There were six main entrances through the wall into the City, five built by the Romans at different times in their occupation of London.

These were, going clockwise from Ludgate in the west to Aldgate in the east: Ludgate, Newgate, Aldersgate, Cripplegate, Bishopsgate and Aldgate. A seventh, Moorgate, was added in Medieval times between Cripplegate and Bishopsgate.

Middle ages

After the Norman conquest in 1066 the city fortifications were added to, as much to protect the Normans from the people of the City of London as to protect London from outside invaders. King William had two fortifications built:

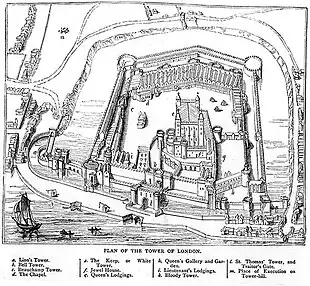

- The White Tower, the first part of the Tower of London to be built, was constructed in 1078 to the east of the city, between Aldgate and the river Thames,

- Baynard's Castle, to the southzwest of the Tower, next to the River Fleet.

A third fortification, Montfichet's Castle, was built to the north west by Gilbert de Monfichet, a native of Rouen, and relative of William.

Later in the medieval period the walls were redeveloped with the addition of crenellations, more gates and further bastions.

City gates

The portals that once guarded the entrances to the City of London through the City Wall were multi-storey buildings that had one or two archways through the middle for traffic, protected by gates and portcullises. They were often used as prisons, or used to display executed criminals to passers-by. Beheaded traitors often had their head stuck on a spike on London Bridge, then their body quartered and spread among the gates.

After the curfew, rung by the bells of St Mary le Bow and other churches at nine o'clock, or dusk, (whichever came earlier) the gates were shut. They reopened at sunrise, or at six o'clock the next morning, whichever came later. Entry was forbidden during these times, and citizens inside the gates were required to remain in their homes. The gates were also used as checkpoints, to check people entering the City, and to collect any tolls that were being charged for the upkeep of the wall, or any other purpose that might require money. It is possible that the wall was maintained for the sole purpose of collecting taxes, and not for defence at all.

The gates were repaired and rebuilt many times. After the restoration of the monarchy in 1660 all of the city gates were unhinged and had their portcullises wedged open, rendering them defenceless, but they were retained as a visible sign of the prestige of the city. Most of the gates were demolished around 1760 due to traffic congestion.

The positions of all the gates are now marked by a main road with the same name, except for Cripplegate, which is a tiny street somewhat north of the position of that gate.

London Bridge

"Old London Bridge was itself fortified against attack. The Southwark end of the bridge was defended by the Great Stone Gate, which was probably completed along with the rest of the bridge in 1209 and was built on the third pier from the bank. In January 1437, the whole gatehouse collapsed into the Thames but was rebuilt from 1465 to 1466. A second line of defence was provided by a drawbridge which spanned the seventh and eighth piers. First mentioned in 1257, it was probably supported by a wooden tower at first, but this was replaced by a stone gatehouse between 1426 and 1428, known as the Drawbridge Gate or the New Stone Gate. The drawbridge served a double function; firstly it could form an impassable barrier to any force attacking from the south and secondly, whilst allowing merchant vessels to pass upstream to the dock at Queenhithe, when lowered it could prevent enemy ships from passing to attack from the rear. The Drawbridge Gate was demolished in 1577. Although the Great Stone Gate was demolished and rebuilt in 1727, it had little military function and was demolished completely in 1760.[1]

17th century

.jpg.webp)

- Lines of Communication were English Civil War fortifications commissioned by Parliament and built around London between 1642 and 1643 to protect the capital from attack by the Royalist armies of Charles I. By 1647 the Royalist threat had receded and Parliament had them demolished.

19th century

- London Defence Positions were a scheme devised in the 1880s to protect London from a foreign invasion landing on the south coast. The positions were a carefully surveyed contingency plan for a line of entrenchments, which could be quickly excavated in a time of emergency. The line to be followed by these entrenchments was supported by thirteen permanent small polygonal forts or redoubts called London Mobilisation Centres, which were equipped with all the stores and ammunition that would be needed by the troops tasked with digging and manning the positions. The centres were built along a 70-mile (113 km) stretch of the North Downs from Guildford to the Darenth valley and one across the Thames at North Weald in Essex. They were quickly viewed as obsolete, and all were sold off in 1907, with the exception of Fort Halstead, which is now the explosives research department of the Ministry of Defence.

World War I

During World War I, part of the London Defence Positions scheme was resurrected to form a stop line in the event of a German invasion. North of the Thames the line was continued to the River Lea at Broxbourne and south of the Thames, it was extended to Halling, Kent, thus linking to the Chatham defences.

World War II and later

Further preparations were made for the defence of London during World War II with the threat of invasion in 1940. These preparations comprised building shelters and fortifications against air attack in the city itself, and preparing defence positions outside the city against the possibility of land attack. GHQ Line was the longest and most important of a number of anti-tank Stop Lines, it was placed to protect London and the industrial heartland of England. GHQ Line ran East from the Bristol area, much of it along the Kennet and Avon canal; it turned south at Reading and wrapped round London passing just south of Aldershot and Guildford; and then headed north through Essex and towards Edinburgh. Inside the GHQ Line there were complete rings of defences, the Outer (Line A), Central (Line B) and Inner (Line C) London Defence Rings.

In the city the Cabinet War Rooms and the Admiralty Citadel were built to protect command and control centres, and a series of deep-level shelters prepared, as refuge for the general population against bombing. In June 1940 under the direction of General Edmund Ironside, concentric rings of anti-tank defences and pillboxes were constructed: The London Inner Keep, London Stop Line Inner (Line C), London Stop Line Central (Line B) and London Stop Line Outer (Line A).[3] Work on these lines was halted weeks later by Ironside's successor, General Alan Brooke,[4] who favoured mobile warfare above static defence.

Following the end of World War II and with the advent of the Cold War era, further hardened defences were prepared in the city to protect command and control structures. A number of citadels were improved, and new ones built, including PINDAR, Kingsway telephone exchange and, possibly, Q-Whitehall, though much of this work is still regarded as secret.

Terrorism defences

London is a major terrorist target, having been subjected to repeated Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) bombings during the Troubles and more recently 7 July 2005 London bombings by Muslim extremists. In the late 1980s the IRA planned a campaign to disrupt the City of London. Two massive truck bombs were exploded in the City of London: the Baltic Exchange bomb on 10 April 1992, and just over a year later the Bishopsgate bombing. The Corporation of the City of London responded by altering the layout of access roads to the city and putting in checkpoints to be manned when the threat level warrants it; these measures are known as the "ring of steel" a name taken from the more formidable defences that, at that time, ringed the centre of Belfast.

The rest of London (with the exception of obvious targets such as Whitehall, the Palace of Westminster, the Royal residences, the airports and some embassies) do not have such overt protection, but London is heavily monitored by CCTV, and many other landmark buildings now have concrete barriers to defend against truck bombs.

See also

Notes

- Pierce, Patricia (2001), Old London Bridge, Headline Book Publishing, ISBN 978-0-747-23493-7 (pp. 318-329)

- The modeby is by artist group craft:pegg, located in Bishops Square, Spitalfields Market

- "London Pillboxes and Anti-Invasion Defences". Archived from the original on 1 February 2010. Retrieved 4 November 2009.

- Alanbrooke, Field Marshal Lord (edited by Alex Danchev and Daniel Todman) (2001). War Diaries 1939-1945. Phoenix Press. ISBN 1-84212-526-5.