Fort Lesley J. McNair

Fort Lesley J. McNair is a United States Army post located on the tip of Greenleaf Point, the peninsula that lies at the confluence of the Potomac River and the Anacostia River in Washington, D.C. To the peninsula's west is the Washington Channel, while the Anacostia River is on its south side. Originally named Washington Arsenal, the fort has been an army post for more than 200 years,[1] third in length of service, after the United States Military Academy at West Point and the Carlisle Barracks. The fort is named for General Lesley James McNair, who was killed in action by friendly fire in Normandy, France during World War II.

| Fort Lesley J. McNair | |

|---|---|

| Part of Joint Base Myer–Henderson Hall | |

| Buzzard Point, Washington, D.C. | |

Fort McNair peninsula from the air | |

Fort Lesley J. McNair | |

| Coordinates | 38.867°N 77.016°W |

| Type | Military base |

| Site information | |

| Controlled by | United States Army |

| Open to the public | No |

| Website | home.army.mil/jbmhh |

| Site history | |

| Architect | Pierre Charles L'Enfant |

| In use | 1791–present |

| Fate | Incorporated into Joint Base Myer–Henderson Hall |

| Garrison information | |

| Garrison | Military District of Washington |

| Occupants | |

History

Early history

The military reservation was established in 1791, on about 28 acres (110,000 m2) at the tip of Greenleaf Point. Major Pierre Charles L'Enfant included it in his plans for Washington, the Federal City, as a significant site for the capital defense.[lower-alpha 1] On L'Enfant's orders, Andre Villard, a French follower of Marquis de Lafayette, placed a one-gun battery on the site. In 1795, the site became one of the first two United States arsenals.[6]

An arsenal first occupied the site, and defenses were built in 1794. However, the fortifications did not halt the invasion of British forces in 1814, who burned down many public government buildings in Washington, D.C., during the War of 1812. Soldiers at the arsenal evacuated north with as much gunpowder as they could carry, hiding the rest in a well as the British soldiers came up the Potomac River after burning the Capitol. About 47 British soldiers found the powder magazines they had come to destroy were empty. Someone threw a match into the well, and "a tremendous explosion ensued," a doctor at the scene reported, "whereby the officers and about 30 of the men were killed and the rest most shockingly mangled."[7]

%252C_Washington%252C_D.C._(Ground_plan_and_views.)_-_NARA_-_305819.jpg.webp)

The remaining soldiers destroyed the arsenal buildings, but the facilities were rebuilt from 1815 to 1821. Eight buildings were arranged around a quadrangle and named the Washington Arsenal. In the early 1830s, four acres of marshland were reclaimed and added to the arsenal. A seawall and additional buildings were constructed. Between 1825 and 1831, the Washington Arsenal penitentiary, which was constructed adjacent to the main arsenal buildings, had a three-story block of cells, administrative buildings, and a shoe factory for teaching prisoners a trade. In 1857, the federal government purchased additional land for the site. By 1860, the arsenal had used one of the first steam presses, developed the first automatic machine for manufacturing percussive caps, and experimented with the Hale Rocket. A large civilian workforce manufactured ammunition at the arsenal, and the site included a large military hospital.[6]

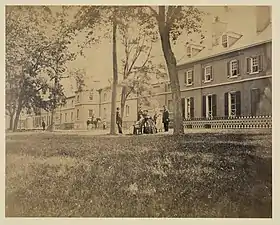

Arsenal, north front. Interior court - group of officers in foreground

Arsenal, north front. Interior court - group of officers in foreground View in Arsenal Yard, general view

View in Arsenal Yard, general view U.S. Arsenal, Washington, D.C., north front, interior court

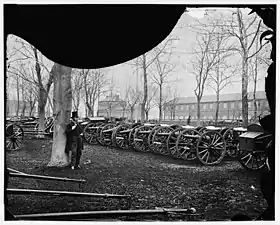

U.S. Arsenal, Washington, D.C., north front, interior court Cannons in 1862 in the Washington Arsenal

Cannons in 1862 in the Washington Arsenal View from the roof of model arsenal

View from the roof of model arsenal Park of Wiard guns at the Arsenal

Park of Wiard guns at the Arsenal Washington, D.C. Wiard 6-pdr. gun at the Arsenal

Washington, D.C. Wiard 6-pdr. gun at the Arsenal Wiard 6 lb. guns, Washington arsenal. Excelsior brigade

Wiard 6 lb. guns, Washington arsenal. Excelsior brigade.jpg.webp) Arsenal Grounds

Arsenal Grounds Batteries of field pieces in the Arsenal

Batteries of field pieces in the Arsenal

The Civil War

During the Civil War, women worked in an ammunition factory at the Washington Arsenal as it served the Union. Many lower-class women—including Irish immigrants—needed wages, especially after male relatives went to war. Women were believed to have nimble fingers, attention to detail, and a tendency to neatness suitable for rolling, pinching, tying, and bundling cartridges with bullets and black powder. Wounded Civil War soldiers were also treated at the Arsenal in a hospital next to the penitentiary that was built prior to the war in 1857.

Accident

On June 17, 1864, fireworks left in the sun outside a cartridge room ignited, killing twenty-one women, many of whom burned to death in flammable hoop skirts. The War Department paid for their funerals, and President Abraham Lincoln attended the joint funeral procession. A monument at Congressional Cemetery commemorates these women. In memory of the many Irish victims, the Irish foreign minister Eamon Gilmore laid a wreath at the Congressional Cemetery memorial in 2014 to commemorate the accident's 150th anniversary.[8][9][10]

Lincoln conspirators' trial

Following the defeat and surrender of the Confederate States of America in the spring of 1865 to end the war, John Wilkes Booth assassinated Lincoln in retribution. Following Booth's death at the hands of Federal troops in Port Royal, Virginia, his conspirators were then apprehended and imprisoned in the Washington Arsenal penitentiary. After being found guilty by a military tribunal, four were hanged in the yard of the penitentiary,[11] and the rest received prison sentences. Among those hanged at what would become Fort McNair was Mary Surratt, the first woman ever executed under federal orders.[1] The military tribunal tried the conspirators in a complex that is known as Ulysses S. Grant Hall. This hall periodically holds public open houses. Each quarter of the hall is open to the public, and people can visit the courtroom and learn more about the trials.

The arsenal was closed in 1881, and the post was transferred to the Quartermaster Corps.[1]

.jpg.webp) An alternate view of the execution, taken from the roof of the Arsenal

An alternate view of the execution, taken from the roof of the Arsenal

Walter Reed

A general hospital, the predecessor to the Walter Reed Army Medical Center, was located at the post from 1898 until 1909. Major Walter Reed found the area's marshlands an excellent site for his research on malaria. Reed's work contributed to the discovery of the cause of yellow fever. Reed died of peritonitis after an appendectomy at the post in 1902. The post dispensary and the visiting officers' quarters now occupy the buildings where Reed worked and died.[1]

20th century

From December 1901 to March 1903, Engineer officer Frederic Vaughan Abbot served on a panel that reported on the feasibility of establishing the United States Army War College at Washington Barracks and reconstructing the site so it could host the headquarters of the Chief of Engineers and the Engineer School.[12] In 1904, the War College's first classes were conducted at Roosevelt Hall,[1][13] the iconic building designed by the architectural firm of McKim, Mead and White.[13] About 90% of the present buildings on the post's 100 acres (0.40 km2) were built, reconstructed, or remodeled by 1908. During World War I, Washington Barracks and the sub‑posts at Camp Leach and Camp A. A. Humphreys, were commanded by Abbot and were home to the school for Engineer officers and the site for enlisting and organizing divisional Engineer regiments for service in France.[12]

The Army Industrial College was founded at McNair in 1924 to prepare officers for high-level posts in Army supply organizations and study industrial mobilization. It evolved into the Industrial College of the Armed Forces.[1] The post was renamed Fort Humphreys in 1935 – a name previously assigned to today's Fort Belvoir.[14] The Army War College was reorganized as the Army-Navy Staff College in 1943 and became the National War College in 1946. The two colleges became the National Defense University in 1976.[1]

The post was renamed in 1948 to honor Lieutenant General Lesley J. McNair, commander of army ground forces during World War II, who was headquartered at the post and was killed during Operation Cobra near Saint-Lô, France, on July 25, 1944. He was killed in an infamous friendly fire incident when errant bombs of the Eighth Air Force fell on the positions of 2nd Battalion, 120th Infantry, where McNair was observing the fighting. Fort McNair has been the headquarters of the Military District of Washington since 1966.[1]

Proposed buffer zone

In 2020, the Department of Defense and Army Corps of Engineers proposed a permanent restricted area of about 250 feet to 500 feet into the Washington Channel along the fort's western bank outlined by buoys and warning signs. This proposal was met with resistance from D.C. city leaders as it would limit access of up to half of the heavily used waterway. In January 2021, the NSA intercepted communications from the Iranian Revolutionary Guard that threatened mounting suicide boat attacks on Fort McNair similar to those used in the USS Cole bombing. The communications also revealed threats to kill Vice Chief of Staff of the Army General Joseph M. Martin and plans to infiltrate and surveil the installation. This contributed to calls to establish the buffer zone and continue increased security.[15] During a March 2021 House Transportation & Infrastructure hearing on a bill prohibiting such a restriction on the Channel, it was noted that the rule, which did not propose the construction of a fence or blast wall, seemed designed to safeguard the views of "rich generals' houses".[16]

January 6, 2021, United States Capitol attack

During the January 6 United States Capitol attack, the senior Congressional leadership was evacuated from the Capitol building to Fort McNair, about two miles away. The Democratic Party leaders evacuated included House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and her senior associates Steny Hoyer and James Clyburn.[17] Incoming Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer was also evacuated.[17]

Senior Senate Republicans evacuated to Fort McNair included outgoing Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell and Senators Chuck Grassley and John Thune. House Republican leaders evacuated to Fort McNair included House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy and Steve Scalise.[17]

Videos recorded by Pelosi's daughter Alexandra Pelosi during those hours showed desperate phone calls imploring government officials to come to the defense of members of Congress were released by the United States House Select Committee on the January 6 Attack in October 2022.[17]

Current status

Fort McNair is today part of the Joint Base Myer–Henderson Hall, the headquarters of the Army's Military District of Washington, and serves as home to the National Defense University, as well as the official residence of the Vice Chief of Staff of the United States Army.

Tenants

National Defense University (NDU)

The National Defense University represents a significant concentration of the defense community's intellectual resources. Initially established in 1976, the university includes the National War College and the Dwight D. Eisenhower School for National Security and Resource Strategy (formerly the Industrial College of the Armed Forces) at Fort McNair, and the Joint Forces Staff College in Norfolk, Virginia. These and other schools are separate entities, but their close affiliation enhances the exchange of faculty expertise and educational resources, promotes interaction among students and faculty, and reduces administrative costs. The National War College and the Eisenhower School concentrate on preparing civilian and military professionals in national security strategy, decision-making, joint and combined warfare, and the resource component of national strategy. The Joint Forces Staff College, established under the Joint Chiefs of Staff in 1946, prepares selected officers for joint and combined duty.

In 1990, the Information Resources Management College was formed as the capstone institution for Defense Information Resource Management education. As such, it provides graduate-level courses in information resources management. The National Defense University also features a first-rate research capability through the Institute for National Strategic Studies. This institute, established in 1984, conducts independent policy analyses and develops policy and strategy alternatives. It also includes a War Gaming and Simulation Center and the NDU Press.

The university has several other educational programs. These include the Capstone program, for general and flag officer selectees; the International Fellows program, which brings NDU almost 100 participants from 50 different countries; and the Reserve Components National Security Course, which offers military education to senior officers of the armed forces.

Inter-American Defense College (IADC)

The Inter-American Defense College is an advanced-studies institute for senior officers of the 25-member nations of the Inter-American Defense Board. Up to three students of the rank of colonel or the equivalent may be sent to the college by each member nation. The students' backgrounds must qualify them to participate in the solution of hemispheric-defense problems.

The officers study world alliances and the international situation, the inter-American system and its role, strategic concepts of war, and engage in a planning exercise for hemispheric defense. The college has been at Fort McNair since 1962.

United States Army Center of Military History (CMH)

In September 1998, the United States Army Center of Military History moved from rented offices in Washington, D.C., to Fort McNair in historically preserved quarters remodeled from its previous use as a commissary and before that as Fort McNair's stables. The center dated from the creation of the Army General Staff historical branch in July 1943 and the gathering of professional historians, translators, editors, and cartographers to record the history of World War II. That effort led to a monumental 79-volume series known as the "Green Books."

Today, the center operates through four divisions. The histories division is the one most involved in writing the histories and providing historical research support to the Army staff. The field program and historical services guides work done at various posts and installations, as well as the work by deployed historical detachments for Army operations, ensures historical information is comprehensive and factual.

Another division is responsible for overseeing the Army museum system and preserving artifacts and artwork that are the army's historical treasure. One such museum, The Old Guard Museum, was located at Fort Myer until it was closed.

References

- Footnotes

- L'Enfant identified himself as "Peter Charles L'Enfant" during most of his life while residing in the United States. He wrote this name on his "Plan of the city intended for the permanent seat of the government of t(he) United States ...."[2] (Washington, D.C.) and on other legal documents. However, during the early 1900s, a French ambassador to the U.S., Jean Jules Jusserand, popularized the use of L'Enfant's birth name, "Pierre Charles L'Enfant". (See: Bowling (2002).) The National Park Service identifies L'Enfant as Major Peter Charles L'Enfant[3] and as Major Pierre (Peter) Charles L'Enfant[4] on its website. The United States Code states in 40 U.S.C. 3309: "(a) In General.—The purposes of this chapter shall be carried out in the District of Columbia as nearly as may be practicable in harmony with the plan of Peter Charles L'Enfant."[5]

- Sources

-

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "Fort McNair History". US Army. Archived from the original on October 6, 2017.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "Fort McNair History". US Army. Archived from the original on October 6, 2017. - "Plan of the city intended for the permanent seat of the government of t[he] United States : projected agreeable to the direction of the President of the United States, in pursuance of an act of Congress passed the sixteenth day of July, MDCCXC, "establishing the permanent seat on the bank of the Potowmac" : [Washington D.C.]". Library of Congress. Archived from the original on December 31, 2017. Retrieved October 14, 2022.

- "Washington, DC Travel Itinerary". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. Archived from the original on December 1, 2009. Retrieved October 14, 2022.

- "Washington Monument--Presidents: A Discover Our Shared Heritage Travel Itinerary". NPS.gov. National Park Service. Archived from the original on February 28, 2010. Retrieved October 14, 2022.

- "40 U.S. Code § 3309 - Buildings and sites in the District of Columbia" (PDF). GovInfo. United States Government Publishing Office. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 2, 2021. Retrieved October 14, 2022.

- "Fort Lesley J. McNair, National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form" (PDF). p. 5. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 2, 2023. Retrieved October 14, 2022.

- "Fort McNair". U.S. Army. Archived from the original on June 21, 2022. Retrieved September 26, 2022.

- LeDoux, Julie (June 24, 2014). "The Washington arsenal explosion". United States Army. Archived from the original on October 7, 2019. Retrieved October 7, 2019.

- "Fireworks, Hoopskirts—and Death: Explosion at a Union Ammunition Plant Proved Fatal for 21 Women". Prologus. 44. Spring 2012. Archived from the original on March 22, 2021. Retrieved October 7, 2019 – via National Archives and Records Administration.

- Carswell, Simon (June 18, 2014). "Tánaiste lobbies for immigration reform in unpredictable US political scene". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on October 22, 2020. Retrieved October 7, 2019.

- Location of the Lincoln conspirators execution gallows within the former Washington Arsenal Penitentiary 38.86624°N 77.0171680°W

- Cullum, George W. (1891–1930). "Frederic V. Abbot, Entries in Cullum's Register, Volumes III to VII". Penelope.uchicago.edu. Chicago, IL: Bill Thayer. Archived from the original on December 15, 2021. Retrieved December 14, 2021.

- "Images of America – Fort Lesley J. McNair" by John Michael ISBN 1439651167

- Decisions of the United States Geographic Board, Google Books

- LaPorta, James (March 21, 2021). "AP sources: Iran threatens US Army post and top general". Associated Press. Archived from the original on August 9, 2021. Retrieved March 23, 2021.

- "Full Committee Markup". House Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure. March 24, 2021. Archived from the original on May 6, 2021. Retrieved May 6, 2021.

- Cohen, Marshall (October 13, 2022). "CNN Exclusive: New footage shows congressional leadership at Fort McNair on January 6, scrambling to save the US Capitol". CNN. Archived from the original on October 13, 2022. Retrieved October 13, 2022.

External links

- Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) No. DC-277, "Army War College, Fort Lesley J. McNair, entrance on P Street between Third & Fourth Streets Southwest, Washington, District of Columbia, DC"

- . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.