Foreign domestic helpers in Hong Kong

Foreign domestic helpers in Hong Kong (Chinese: 香港外籍家庭傭工) are domestic workers employed by Hongkongers, typically families. Comprising five percent of Hong Kong's population, about 98.5% of them are women. In 2019, there were 400,000 foreign domestic helpers in the territory. Required by law to live in their employer's residence, they perform household tasks such as cooking, serving, cleaning, dishwashing and child care.[1]

| Foreign domestic helpers in Hong Kong | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 香港外籍家庭傭工 | ||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 香港外籍家庭佣工 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

From October 2003 the employment of domestic workers was subject to the unpopular Employees' Retraining Levy, totalling HK$9,600 for a two-year contract. It had not been applied since 16 July 2008 when it was finally abolished in 2013. Whether foreign workers should be able to apply for Hong Kong residency is a subject of debate, and a high-profile court battle for residency by a foreign worker failed.[2][3]

The conditions of foreign domestic workers are being increasingly scrutinised by human-rights groups and are criticised as tantamount to modern slavery. Documented cases of worker abuse, including the successful prosecution of an employer for subjecting Erwiana Sulistyaningsih to grievous bodily harm, assault, criminal intimidation and unpaid wages, are increasing in number.[4] In March 2016, an NGO, Justice Centre, reported its findings that one domestic worker in six in Hong Kong were deemed to have been forced into labour.[5]

Terminology

In Hong Kong Cantonese, 女傭 (maid) and 外傭 (foreign servant) are neutral, socially-acceptable words for foreign domestic helpers. Fei yung (菲傭, Filipino servant) referred to foreign domestic helpers, regardless of origin, at a time when most foreign domestic helpers were from the Philippines. The slang term bun mui (賓妹, Pinoy girl) is widely used by local residents.[6]

In Chinese-language government documentation, foreign domestic helpers are referred to as 家庭傭工 (domestic workers) "of foreign nationality" (外籍家庭傭工)[7] or "recruited from abroad" (外地區聘用家庭傭工).[8] Although the government uses words with the same meanings in English-language documentation, it substitutes the term "domestic helper" for "domestic worker".[9][10] Director of the Bethune House shelter for domestic workers Edwina Antonio has criticised the term "helper", saying that the migrants do dirty jobs; calling them "helpers" strips them of the dignity accorded workers and implies that they can be mistreated, like slaves.[11]

History

Faced with a poor economy in 1974, Filipino President, Ferdinand Marcos implemented a labour code which began his country's export of labour in the form of overseas workers. The Philippine government encouraged this labour export to reduce the unemployment rate and enrich its treasury with the workers' remittances.[12] The economy of the Philippines became increasingly dependent on labour export; in 1978 labour-export recruiting agencies were privatised, and became a cornerstone of the economy.[13]

Increasing labour export from the Philippines coincided with the economic rise of Hong Kong during the late 1970s and early 1980s. When the People's Republic of China implemented wide-reaching economic reform in the late 1970s and initiated trade with other countries,[14] Hong Kong became mainland China's biggest investor.[15] Labour-intensive Hong Kong industries moved to the mainland, and high-profit service industries in the territory (such as design, marketing and finance) expanded dramatically. To deal with the resulting labour shortage and increase in labour costs, the female labour force was mobilised. Two-income families sought help to manage their households, creating a demand for domestic workers. Female participation in the workforce increased, from 47.5 percent in 1982 to 54.7 percent in 2013.[11] Families began hiring foreign domestic workers from the Philippines, with the number of workers steadily increasing during the 1980s and 1990s.[15]

Prevalence and demographics

Singapore, Hong Kong and Taiwan are considered attractive destinations by those seeking employment as domestic workers.[16] According to Quartz, Hong Kong has one of the highest densities of foreign domestic workers in the world and its pay scale is a benchmark for other jurisdictions. Since the mid-1970s, when the foreign-domestic-helper policy was initiated, the number of workers has increased to around 300,000. At the end of 2013, there was an average of one foreign domestic worker for every eight households overall;[11] in households with children, the average is one for every three. Foreign domestic helpers are about 10 percent of the working population.[11] In December 2014 the number of migrant workers employed as helpers was over 330,000, 4.6 percent of the total population; the vast majority were female.[1]

Before the 1980s and increased prosperity on the mainland, Chinese domestic workers were dominant.[11] Until the 1990s, workers then came primarily from the Philippines; the percentage is now shifting from Philippine workers to Indonesian and other nationalities. During the 1990s Indonesia and Thailand followed the Filipino model of labour export to deal with domestic economic crises, and Hong Kong families began hiring workers from those countries as well.[15] The Indonesians provided competition, since those workers were often prepared to accept half the minimum wage.[11]

According to the Immigration Department, in 1998 there were 140,357 Filipino domestic workers in Hong Kong and 31,762 from Indonesia.[17] In 2005, official figures indicated 223,394 "foreign domestic helpers" in the territory; 53.11 percent were from the Philippines, 43.15 percent from Indonesia and 2.05 percent from Thailand.[18] In 2010, the respective numbers were 136,723 from the Philippines (48 percent), 140,720 from Indonesia (49.4 percent), 3,744 from Thailand (1.3 percent), 893 Sri Lankans, 568 Nepalese and 2,253 of other nationalities. Vietnamese are not permitted to work in Hong Kong as domestic workers for what authorities call "security reasons" linked to (according to one lawmaker) historical problems with Vietnamese refugees.[17]

Attempts to import workers from Myanmar and Bangladesh have failed.[19] Indonesian president Joko Widodo has reportedly said that he considers the export of domestic labour a national embarrassment, pledging that his government will end the practice.[20][21] In a 2001 survey conducted by the Hong Kong's Census and Statistic Department, over half, 54.8%, of foreign domestic helpers have completed secondary studies.[22] For many foreign domestic helpers, they consider themselves unemployed professional since they hold a secondary degree. Furthermore, 60.4% of helpers are fluent in speaking English compared to only 11.2% of helpers who speak Cantonese fluently. In February 2015 there were 331,989 foreign domestic workers in Hong Kong, of which 166,743 were from the Philippines – an increase of 7,000 from the previous year, with the number of Indonesians remaining static.[19]

Recruitment

Foreign domestic workers are recruited primarily by a large number of specialised agencies, with local firms connected to correspondents in the workers' home countries.[23] Agencies are paid by employers and workers, and are regulated according to the Employment Ordinance and Employment Agency Regulations.[1][24] Local agencies dealing with workers from the Philippines are accredited by the Philippine consulate.[25] To hire an Indonesian worker, an employer must use an agent, whereas there is no similar requirement for Filipino workers.[1][23][26] Although agency fees are regulated by law to 10 percent of one month's salary, some agencies in the workers' countries charge commissions and "training" fees which take several months to pay off.[26][27] The Philippine government outlawed commissions in 2006, and employment agencies may only charge fees.[28]

Employment regulations

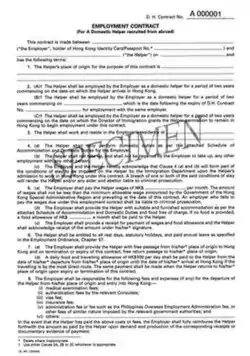

The government of Hong Kong has drawn up rules and regulations concerning the employment, labour and conditions of stay of foreign domestic helpers. Since 2003, all foreign domestic helpers are required by law to be live-in.[11] An employer and employee are required to enter into a standard, two-year contract specifically for the employment of foreign domestic helpers.[10] Employer regulations include:[29]

- Household income of at least HK$15,000 (US$1,920) per month for each foreign domestic helper employed

- A levy of HK$9,600 for employing a foreign domestic helper, for the duration of a 2-year contract[29] (abolished 31 July 2013)

- Free medical treatment for the foreign domestic helper

- A monthly salary of no less than the minimum allowable wage (HK$4,630) set by the government [30]

Helpers' rights and obligations include:

- To perform only the domestic duties outlined in the employment contract

- To not accept other employment during the effective period of the contract[29]

- To work and live in the employer's place of residence, and to be provided with suitable living accommodation with reasonable privacy[29]

- One rest day (a continuous period of not less than 24 hours) every week[29]

- Minimum 7 days to maximum 14 days of paid annual leave based on length of service[31]

- 12 days of statutory holidays during an entire year[31]

Minimum allowable wage

Foreign domestic workers' wages are subject to a statutory minimum, a breach of which is sanctionable under the Employment Ordinance. An employer convicted of paying less than the minimum allowable wage (MAW) is subject to a maximum fine of HK$350,000 and three years' imprisonment.[32]

Helpers' minimum wages are inflation-adjusted annually for contracts about to be signed, and apply for the duration of the contract. They were reduced by HK$190 (five percent) in 1999.[33] In April 2003, another deflationary period, the government announced a HK$400 reduction in pay (to HK$3,270) "due to the steady drop in a basket of economic indicators since 1999."[34] The minimum allowable wage was raised by HK$80, to HK$3,480 per month, for contracts signed on or after 6 June 2007.[35] Another HK$100 cost-of-living adjustment took effect for all employment contracts signed on or after 10 July 2008, increasing the minimum wage to HK$3,580 per month.[32] The minimum allowable wage was reset to HK$3,740 per month on 2 June 2011,[36] and raised to HK$3,920 per month for contracts signed from 20 September 2012 onwards.[37]

The MAW has been criticised by workers' and welfare groups for making FDWs second-class citizens. The statutory minimum wage does not apply to them; although the MAW is HK$3,920, a local worker working a 48-hour week would earn HK$6,240 if paid at the minimum hourly wage of HK$30 (as of 30 March 2015).[1][11][38] The International Domestic Workers Federation has complained that the MAW rose by only 3.9 percent (or HK$150) from 1998 to 2012, failing to keep pace with Hong Kong's median monthly income (which rose over 15 percent during the same period).[11] Since Hong Kong is a benchmark market for Asian migrant workers, there is pressure to keep wages low.[11] Wages were also held in check by competition from Indonesian workers, who began arriving in large numbers during the 1990s. Since then, workers from other Asian countries (such as Bangladesh and Nepal) may be willing to work for less than the MAW.[11]

Employees' Retraining Levy

During a recession in 2003, the Hong Kong government imposed a HK$400 monthly Employees' Retraining Levy for hiring a foreign domestic helper under the Employees Retraining Ordinance, to take effect on October 1.[39] The tax, proposed by the Liberal Party in 2002 to tackle a fiscal deficit,[40] was introduced by Donald Tsang as part of the government's population policy when he was Chief Secretary for Administration.[41] Although Tsang called foreign and local domestic workers two distinct labour markets, he said: "Employers of foreign domestic helpers should play a role in helping Hong Kong in ... upgrading the local workforce."[42]

According to Government Policy Support and Strategic Planning, the levy would be used to retrain the local workforce and improve their employment opportunities.[34] The government said that the extension of the levy to domestic helpers would remove the disparity between imported and local workers.[43] According to The Standard, it was hoped that fewer foreign maids would be employed in Hong Kong. The Senate of the Philippines disagreed with the Hong Kong government, denounced the levy as "discriminatory" and hinted that it would take the issue to the International Labour Organization. Senate president Franklin Drilon said that a tax on domestic workers countered Hong Kong's free-market principles and would damage its reputation for openness to foreign trade, investment and services.[44]

Earlier that year the minimum wage for foreign domestic helpers was lowered by the same amount, although the government said the reduction in the minimum wage and imposition of the levy were "unrelated";[34] lawyers for the government called the moves an "unfortunate coincidence".[40] The measure was expected to bring HK$150 million annually into government coffers.

Thousands of workers, fearing that the financial burden would be passed to them, protested the measures.[33] The government, defending the measures as necessary in Hong Kong's changing economy, said that foreign domestic workers were still better paid than their counterparts in other Asian countries; according to James Tien, the monthly wage of Filipina maids in Singapore was about HK$1,400 and $1,130 in Malaysia.[40]

In 2004 a legal challenge was mounted, asserting that the levy on employers was unlawful as a discriminatory tax. In January 2005 High Court Justice Michael Hartmann ruled that since the levy was instituted by law it was not a tax, but a fee for the privilege of employing non-local workers (who would not otherwise be permitted to work in Hong Kong).[45] In 2007 the Liberal Party urged the government to abolish the Employees' Retraining Levy as a part of its District-Council election platform, saying that the HK$3.26 billion fund should be used as originally intended: to retrain employees.[46] In an August 2008 South China Morning Post column, Chris Yeung called the case for retaining the levy increasingly morally and financially weak: "Middle class people feel a sense of injustice about the levy".[3] According to Regina Ip, the levy had lost its raison d'être.[47] In 2013 the government abolished the levy in the Chief Executive's policy address, effective 31 July.[20]

Levy waiver controversy

As part of "extraordinary measures for extraordinary times" (totalling HK$11 billion) announced by Donald Tsang on 16 July 2008,[3] the levy would be temporarily waived[48] at an estimated cost of HK$2 billion.[3] In the Chinese press, the measures were mockingly called 派糖 (handing out candy).[49]

The levy would be waived for a two-year period on all helpers' employment contracts signed on or after 1 September 2008, and would not apply to existing contracts. The Immigration Department said it would not reimburse levies, which are prepaid semiannually. The announcement resulted in confusion and uncertainty for workers.[50] Before Tsang's October policy address, Chris Yeung called the waiver a "gimmick dressed up as an economic relief initiative, designed to boost the administration's popularity".[3][42]

Maids' representatives said that when the waiver was announced, the guidelines were unclear and had no implementation date. Employers deferred contracts or dismissed workers pending confirmation of the effective date, leaving them in limbo. They protested the uncertainty, demanding an increase in their minimum wage to HK$4,000.[51] Employers reportedly began terminating their helpers' contracts, stoking fears of mass terminations. On 20 July Secretary for Labour and Welfare Matthew Cheung announced that the waiver commencement date would be moved up by one month, and the Immigration Department temporarily relaxed its 14-day re-employment requirement for helpers whose contracts had expired.[52]

On 30 July the Executive Council approved the suspension of the levy for two years, from 1 August 2008 to 31 July 2010. After widespread criticism, the government said that maids with advanced contract renewals would not be required to leave Hong Kong; employers would benefit from the waiver by renewing contracts within the two-year period. According to the government, some employers could benefit from the waiver for up to four years.[53] The effect of turning a two-year moratorium into four-year suspension was denounced by newspapers across the political spectrum,[3] and the levy itself was called "farcical" in a South China Morning Post editorial.[54] Stephen Vines wrote: "The plan for a two-year suspension of the levy ... provides an almost perfect example of government dysfunction and arrogance",[55] and Albert Cheng said that the controversy exposed the "worst side of our government bureaucracy".[56] Columnist Frank Ching criticised senior officials for living in ivory towers, and said that there would have been no disruption if the government had suspended payment immediately and repaid those who had prepaid.[42] Hong Kong Human Rights Monitor called for the levy's permanent abolition, saying that the temporary two-year waiver was discriminatory and criticising the confusion and inconvenience caused to employers by the Immigration Department because the policy had not been thought through.[57]

Administrative crush

On the morning of 1 August the Immigration Department issued 2,180 passes to workers and agents to collect visas and submit applications to work in Hong Kong, promising to handle all applications submitted. Offices opened one hour earlier than usual, added staff and extended their hours to guarantee that all 2,180 cases would be processed.[58] The Philippine consulate also expected a large workload as a result of the rehiring provisions.[59] Chinese newspapers published articles calculating how households could maximise their benefits under the waiver rules. Street protests on 3 August decried the waiver's unfairness and its burden on the Immigration Department. According to one protester, the waiver would teach households how to use legal loopholes.[47]

The West Kowloon Immigration office in Yau Ma Tei processed 5,000 advance contract renewals and 7,400 regular renewals in August 2008. Despite the availability of online booking for slots at its five branch offices, the daily quota on the number of applications being processed resulted in overnight queues. Positions in the waiting line were illegally sold for up to HK$120.[60]

Legislative Council debate

The government was required to move an amendment in the Legislative Council (LegCo) to suspend the levy in accordance with the Executive Council decision. Faced with calls to abolish the levy, the government was adamantly opposed; according to the Secretary for Labour and Welfare, the HK$5 billion fund would only support the Employment Retraining Board for four or five years if the levy was permanently waived.[61]

Regina Ip began a campaign to abolish the levy, and tabled an amendment at LegCo. The government said that it would attempt to rule it out of order on the grounds that it would breach rule 31(1) of the Rules of Procedures, which prohibit amendments impacting government revenue.[62] Ip compared this stance with a 2005 High Court decision that the Employees' Retraining Levy was not a tax. According to the government, a bill to abolish the levy would breach Article 74 of Hong Kong Basic Law[63] and it would take Article 74 to the central government for interpretation. Legislators and commentators called this proposal a "nuclear bomb", and a University of Hong Kong academic said that reinterpretation would be a "totally disproportionate ... route to resolve this dispute."[64]

Under pressure from legislators, the government (through the Executive Council) agreed to extend the levy's suspension from two to five years. The amendment for the five-year suspension, one of several proposed amendments to the Employees Retraining Ordinance Notice 2008, was tabled by the Democratic Alliance for the Betterment and Progress of Hong Kong and would apply to first-time and renewed contracts and visas issued between 1 August 2008 and 31 July 2013.[65]

Grievances

Foreign domestic workers and their supporters, including activists and employers, have periodically staged rallies protesting what they perceive as discriminatory treatment on the part of the Hong Kong government. Grievances include discrimination, the minimum wage and the two-week stay limit at the end of a domestic worker's employment contract. According to the Hong Kong Human Rights Monitor (HKHRM), foreign domestic helpers face discrimination from the Hong Kong government and their employers.[66]

A 2013 Amnesty International report on Indonesian migrant domestic workers, "Exploited For Profit, Failed By Governments – Indonesian Migrant Domestic Workers Trafficked To Hong Kong", suggested that they may be the victims of serious human- and labour-rights violations in Hong Kong and some regulations make the problem worse.[67] Abuses noted by AI include confiscation of travel documents, lack of privacy, pay below the Minimum Allowable Wage and being "on call" at all hours. Many are subjected to physical and verbal abuse by their employers, and are forced to work seven days a week.[68][69]

Systemic exploitation

Many migrant workers have little education, little knowledge of the law and their rights, and leave home to support their families. They fall victim to agents (official and unofficial), unscrupulous officials and a lack of legal protection at home and in their host countries. The debts they incur to secure employment overseas may lock them in a cycle of abuse and exploitation.[21]

There is criticism in the Philippines that the country is one of the biggest human traffickers in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations. In the Manila Standard, Alejandro Del Rosario criticised the government for continuing its 1960s policy of labour export instead of focussing on domestic production and job creation (allowing the program to expand, contributing to the brain drain).[20] Amnesty International suggests that a lack of oversight allows criminal syndicates to profit from foreign workers, who are often unaware of their legal rights in their host country.[27] AI's 2013 report alleges that many Indonesians are victims of forced human trafficking,[67] and criticises the Indonesian and Hong Kong governments for having "failed to take adequate action to enforce domestic legislation in their own territories which could have protected migrant workers from trafficking, exploitation and forced labour ... In particular, they have not properly monitored, regulated or punished recruitment and placement agencies who are not complying with the law."[67]

In 2014 and 2015 several incidents involving worker mistreatment surfaced, indicating that employment agencies often neglect workers' rights or are complicit in the cycle of abuse; there have also been many instances of failure to provide service to employers. According to media reports, between 2009 and 2012 the Consumer Council in Hong Kong received nearly 800 complaints about agencies. Many complaints concerned workers who did not match the descriptions provided, to the extent that it was suspected that the agencies deliberately misrepresented the workers' experience.[24] The 2015 death of Elis Kurniasih, awaiting her work visa before beginning employment, exposed grey areas and legal loopholes in the Employment Agency Regulations;[24][70] Kurniasih was crushed to death by falling masonry at an agency boarding house in North Point.[1][71] Worker protections against illegal fees, unsanitary accommodations and lack of insurance were criticised as inadequate.[24][70]

Right of abode

Under the Immigration Ordinance a foreigner may be eligible to apply for permanent residency after having "ordinarily resided" in Hong Kong for seven continuous years, and thus enjoy the right of abode in Hong Kong.[72] However, the definition of "ordinary residency" excludes (amongst other groups) those who lived in the territory as foreign domestic helpers;[73] this effectively denied foreign workers the rights of permanent residents (including the right to vote), even if they had lived in Hong Kong for many years.[66] Since 1997, section 2(4) of the Immigration Ordinance has stated that "a person shall not be treated as ordinarily resident in Hong Kong while employed as a domestic helper who is from outside Hong Kong".[74] Therefore, foreign domestic helpers only receive temporary status since they enter Hong Kong with a temporary visa.[75] However, many workers have been able to receive permanent residency through marriages and relationships. These relationships can be out of love or be a mutual arrangement, allowing the foreign domestic worker to apply for a dependent's visa. In some cases, these arrangements can lead to abuse and exploitation by the permanent resident. In 2011, the issue of foreign workers applying for Hong Kong residency was debated; since one million families live under the poverty line in the territory, some political parties argued that Hong Kong has insufficient welfare funding to support 300,000 foreign workers if they can apply for public housing and social-welfare benefits. The Court of First Instance found in Vallejos v Commissioner of Registration that this definition of "ordinarily resident" contravenes Article 24 of the Basic Law. The latter stipulates, "Persons not of Chinese nationality who have entered Hong Kong with valid travel documents, have ordinarily resided in Hong Kong for a continuous period of not less than seven years and have taken Hong Kong as their place of permanent residence before or after the establishment of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region", feeding speculation that domestic helpers could obtain the right of abode.[76] An appeal was made to the Court of Appeal of the High Court, which overturned the judgment of the Court of First Instance. The plaintiffs then appealed to the Court of Final Appeal, which ruled against them in a unanimous judgment.

Two-week rule

The government requires foreign domestic helpers to leave Hong Kong within two weeks of the termination of their employment contract, unless they find another employer (the two-week rule).[29] According to Hong Kong Human Rights Monitor, this is a form of discrimination against foreign domestic helpers (who are almost all Southeast Asian); this limitation is not enforced for other foreign workers.[66] The two-week rule has been condemned by two United Nations committees: the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women and the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.[77]

According to human-rights groups, the two-week rule may pressure workers to remain with abusive employers.[66][78] In 2005, the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights urged the government to "review the existing 'two-week rule' ... and to improv[e] the legal protection and benefits for foreign domestic workers so that they are in line with those afforded to local workers, particularly with regard to wages and retirement benefits."[79] The following year, the UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women called on the government to "repeal the 'two-week rule' and to implement a more flexible policy regarding foreign domestic workers. It also calls upon the state party to strengthen its control of employment agencies and to provide migrant workers with easily accessible avenues of redress against abuse by employers and permit them to stay in the country while seeking redress."[80] The two-week and live-in rules were criticised by the United Nations Human Rights Committee in 2013.[67]

Abuse by employers

Although the Hong Kong government has enacted legislation which nominally protects migrant workers, recourse is time-consuming and the costs considerable.[11] The legal process can take up to 15 months to reach the District Court or Labour Tribunal, during which workers have no income.[77]

Welfare groups have expressed concerns about the treatment of this segment of the Hong Kong workforce, and the 2014 Erwiana Sulistyaningsih abuse case (which attracted international news headlines) focused on the plight of foreign workers in the territory.[11][27] Thousands took to the streets, demanding justice for Sulistyaningsih.[68] Although the government calls her case an isolated one, welfare groups say that many workers are victims of "modern-day slavery" and abuse by employers.[11][81] Hong Kong Human Rights Monitor reported that a substantial percentage of workers are mistreated by their employers; of 2,500 workers interviewed, at least 25 percent said they had experienced violations of their contract (including pay less than the MAW and being denied their mandatory weekly day of rest and statutory holidays). More than 25 percent had also experienced physical and verbal abuse, including a "significant incidence" of sexual abuse.[66] According to Caritas Hong Kong, their Asian Migrant Worker Social Service Project helpline received over four thousand calls from workers and 53 workers received assistance to remain in Hong Kong and pursue their claims.[77][82][83][84] According to Belthune House executive director Adwina Antonio, the shelter dealt with 7,000 cases of alleged abuse in the first three-quarters of 2013 (compared with 3,000 for all of 2012).[11]

Contributing factors include "artificially low wages" and the live-in requirement.[11][23] Many workers accumulate six to twelve months' debt to intermediaries for commissions, although these commissions are limited by law to 10 percent of the first month's pay.[11][23][27][38] The ease with which foreign workers may be deported and the difficulty of finding employment abroad deters them from reporting violations or discrimination.

Live-in requirement

Since workers are required to live with their employers, they are vulnerable to working long hours; according to Amnesty International and welfare groups, some workers routinely work 16 to 18 hours a day[1][11] and have no escape from abuse.[1][11][23] In addition, workers are given a curfew. The dynamic between the worker and employer depends on how the employer views themselves and how they perceive workers. In many homes where the employer is Chinese, the foreign helper tends to be seen as socially inferior.[75] As for the living conditions of the live-in requirement, it varies from a private room to a mat in the middle of the living room. The live-in requirement also creates difficulties between the employer and helper when forming public and private boundaries.

Philippine government policy

Filipino workers have protested Philippine government targeting of overseas Filipino workers, and a 1982 protest opposed Executive Order No. 857 (EO-857) implemented by Ferdinand Marcos. According to the order, overseas contract workers were required to remit 50 to 70 percent of their total earnings through authorised government channels only.[85] Migrant-worker groups say that overseas Filipino workers must pay up to PHP150,000 ($3,400) in government and recruiting-agency fees before they can leave the country.[38]

In 2007, the Philippine government proposed a law requiring workers to submit to a "competency training and assessment program" which would cost them PHP10,000 to P15,000 (US$215 to US$320) – about half their average monthly salary (typically US$450). According to the Philippine Department of Labor and Employment, the policy would help protect domestic overseas workers from abuse by employers.[86] Government agencies receive a total of about PHP21 billion ($470 million) a year from foreign workers in police clearances, National Bureau of Investigation and passport fees, membership in the Overseas Workers Welfare Administration, local health insurance and Philippine Overseas Employment Agency and Home Development Mutual Fund fees.[38] Although charges by Indonesian agencies for dormitory housing, lessons in Cantonese, housework and Chinese cuisine were capped at about HK$14,000 by the government in 2012, interest is excluded from the cap.[28]

In 2012, Bloomberg reporters suggested that many agencies contract with workers to convert sums owed before their arrival in Hong Kong into "advances" from moneylenders (bypassing Hong Kong law).[1][28] Since Hong Kong remains one of the more democratic states that migrant workers go for employment, it is also a safeguard for political activism. Since the Filipino government's policies of remittance and services have been instituted there have been protests by those that have traveled to Hong Kong in hopes of catching the attention of the governments where these workers originate.

In 2005, the Consulate Hopping Protest and the Hall of Shame Awards were some of the first events organized by domestic service workers. During these events, hundreds of domestic workers marched through the streets of Hong Kong up to several consulates, including the United States, China, the Philippines, and Indonesia, to give "awards" to the heads of office. These awards were fabricated with jokes and slanders of their grievances to the heads of state of the respected consulates. [87]

Indonesian government policy

The Indonesian consulate requires Indonesian domestic workers to use the services of employment agencies. The consulate can do this because the Hong Kong Immigration Department will only accept applications for employment visas that have been endorsed by consulates.[88]

Hong Kong government policy

According to Time, the two-week rule and live-in requirement protect Hong Kong employers of foreign workers. The government argues that the two-week rule is needed to maintain immigration control, preventing job-hopping and imported workers working illegally after their contracts end. "However, it does not preclude the workers concerned from working in Hong Kong again after returning to their place of domicile."[89] The government implies that in the absence of these rules, workers can easily leave unsatisfactory employers (creating the disruption of having to find a new employee and incurring an additional fees for a new contract).[26] In early 2014, the government further impeded labour mobility by no longer renewing the visas of workers who change employers more than three times in a year.[11]

Hong Kong regards the Erwiana Sulistyaningsih case as isolated, and its labour minister pledged to increase regulation, enforcement and employment-agency inspections.[23][68][81] It has conducted several raids on migrant workers accused of not living at their employer's residence.[90][91] However, Robert Godden of Amnesty Asia-Pacific said: "The specifics, many of the factors leading to the abuse [of Erwiana], can be applied to thousands of migrant domestic workers: underpayment, restrictions on movement; you can see that she was heavily indebted by the illegal recruitment fees charged by the agency, and you can see that she didn't know how to access justice."[68] In 2014, the Labour Department prosecuted an employer who allegedly abused Rowena Uychiat during her nine-month employment.[92]

In March 2016, an NGO, Justice Centre, reported its findings that deemed one domestic worker in six in Hong Kong to have been forced into labour. It criticised the government for being in denial that Hong Kong is a source, destination and transit area for human trafficking and forced labour, and said Hong Kong lags behind other countries in having a comprehensive set of laws and policies to tackle forced labour or trafficking.[5]

The government declared mandatory vaccination for helpers after cases of Covid-19 variants were discovered in late April, but reversed the decision in May following criiticisms from labour organisations of discrimination against these workers whereas other foreign workers were not forced to vaccinate.[93]

See also

References

- Bong Miquiabas (31 March 2015). "After Another Nightmare Surfaces in Hong Kong's Domestic Worker Community, Will Anything Change?". Forbes.

- Man, Joyce (29 March 2012). "Hong Kong Court Denies Residency to Domestic Workers". Time.

- Chris Yeung (3 August 2008). "HK needs better leadership, Mr Tsang". South China Morning Post. Hong Kong. pp. A10.

- "Hong Kong woman guilty in Indonesian maid abuse case". Associated Press. Retrieved 10 February 2015.

- "NGO 'far from surprised' after HK ranks alongside North Korea, Iran, Eritrea in slavery index". June 2016.

- Catherine W. Ng (October 2001). "Is there a need for race discrimination legislation in Hong Kong?" (PDF). Centre for Social Policy Studies, Hong Kong Polytechnic University. pp. 24–26. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 February 2007. Retrieved 18 March 2007.

- 輸入勞工: 外籍家庭傭工 (in Chinese). Labour Department of HKSAR. 5 January 2007. Archived from the original on 5 July 2007. Retrieved 18 March 2007.

- 從香港以外地區聘用家庭傭工的僱傭合約 (in Chinese). Immigration Department of HKSAR. 14 February 2007. Archived from the original on 15 March 2007. Retrieved 18 March 2007.

- "Importation of Labour: Foreign Domestic Helpers". Labour Department of HKSAR. 5 June 2007. Archived from the original on 20 April 2007. Retrieved 26 June 2007.

- "Employment Contract for a Domestic Helper Recruited from Outside Hong Kong". Immigration Department of HKSAR. 14 February 2007. Archived from the original on 20 March 2007. Retrieved 18 March 2007.

- Lily Kuo (19 February 2014). "How Hong Kong's "maid trade" is making life worse for domestic workers throughout Asia". Quartz.

- Odine de Guzman (October 2003). "Overseas Filipino Workers, Labor Circulation in Southeast Asia, and the (Mis)management of Overseas Migration Programs". Kyoto Review of Southeast Asia (4). Archived from the original on 4 May 2007. Retrieved 18 March 2007.

- Vivienne Wee; Amy Sim (August 2003). "Transnational labour networks in female labour migration: mediating between Southeast Asian women workers and international labour markets" (PDF). Working Paper Series. City University of Hong Kong (49). Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 February 2007. Retrieved 18 March 2007.

- Vicky Hu (May 2005). "The Chinese Economic Reform and Chinese Entrepreneurship" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 March 2009. Retrieved 18 March 2007.

- Neetu Sakhrani (December 2002). A Relationship Denied: Foreign Domestic Helpers and Human Rights in Hong Kong (DOC) (Report). Civic Exchange. Retrieved 20 June 2010.

- "Choose recognised agencies when hiring domestic helpers: Human Resources Deputy Minister". NST Online.

- Wan, Adrian (10 November 2010). "Push to lift ban on maids from Vietnam", South China Morning Post

- "Entry of Foreign Domestic Helpers" (PDF). Hong Kong SAR Government Information Centre. November 2006. Retrieved 18 March 2007.

- "Number of Filipino domestic workers in HK at all-time high". Rappler. 17 April 2015.

- "PHL welcomes Hong Kong's scrapping of domestic helpers' levy". GMA News Online. 16 January 2013.

- "Why migrant workers must not be forgotten". The Jakarta Post. 30 April 2015.

- "Press Release (2 Jan 2001) :Survey on ethnic minorities in Hong Kong released | Census and Statistics Department". www.censtatd.gov.hk. Retrieved 8 December 2020.

- Per Liljas. "Abused Indonesian Maid Could Sue Hong Kong Government, Lawyer Says". Time.

- "Time to regulate foreign domestic helper agencies". EJ Insight. 14 April 2015.

- "Ex-labor attaché to HK 'probably guilty' – PH lawmakers". Rappler. 19 March 2015.

- Liljas, Per (15 January 2014). "Exploited Indonesian Maids Are Hong Kong's 'Modern-Day Slaves'". Time.

- "Hong Kong′s domestic workers ′treated worse than the dogs′". Deutsche Welle. 8 March 2015.

- Sheridan Prasso (13 November 2012). "Indentured Servitude in Hong Kong Abetted by Loan Firms". Bloomberg L.P.

- "Quick Guide for the Employment of Domestic Helpers from Abroad (ID 989)". Immigration Department of HKSAR. 25 April 2008. Archived from the original on 9 April 2008. Retrieved 18 March 2007.

- "HelperPlace – Domestic Helper Salary Rules in Hong Kong". Social Employment Agency. 14 August 2020.

- "HelperChoice – Types of Domestic Helper Holidays in Hong Kong". Social Employment Agency. 23 March 2019.

- "Minimum wage increased for foreign domestic helpers" (Press release). Hong Kong Government. 9 July 2008. Retrieved 1 August 2008.

- "HK maids march against pay cuts". BBC News. 23 February 2003. Retrieved 18 March 2007.

- "Foreign domestic helper levy in effect from Oct" (Press release). Hong Kong Government. 29 August 2003. Archived from the original on 17 June 2008. Retrieved 1 August 2008.

- "Adjustment of minimum allowable wage for foreign domestic helpers" (Press release). Hong Kong Government. 5 June 2007. Archived from the original on 12 March 2008. Retrieved 1 August 2008.

- "FAQ: Foreign Domestic Helpers". Hong Kong Government, Immigration Department. 2 June 2011. Archived from the original on 8 February 2010. Retrieved 6 July 2011.

- "Practical Guide For Employment of foreign domestic helpers – What foreign domestic helpers and their employers should know", Labour Department, Hong Kong, September 2012

- Lorie Ann Cascaro, The Diplomat. "Overseas Filipino Workers: Organizing for Fairer Conditions". The Diplomat.

- "FDH employers to pay employees retraining levy from October 1, 2003". Government of Hong Kong. 25 September 2003. Retrieved 5 August 2003.

- Daniel Hilken (8 September 2004). "Challenge to pay cuts". The Standard. Hong Kong. Archived from the original on 22 May 2011. Retrieved 1 August 2008.

- "Population policy – Donald Tsang unveils population report" (Press release). 26 February 2003. Archived from the original on 17 March 2008. Retrieved 5 August 2008.

- Frank Ching (26 July 2008). "Walking smack into the maid levy fiasco". "Observer", South China Morning Post.

- Cannix Yau (5 March 2003). "Maids look into legal challenge". The Standard. Hong Kong. Archived from the original on 22 May 2011.

- "No upside to levy". The Standard. Hong Kong. 1 March 2003. Archived from the original on 22 May 2011.

- Jonathan Li; Sylvia Hui (5 January 2005). "Wage cut for maids ruled lawful". The Standard. Hong Kong. Archived from the original on 22 May 2011. Retrieved 1 August 2008.

- "Liberal Party to field 60 in district polls". The Standard. Hong Kong. 8 October 2007. Archived from the original on 22 May 2011. Retrieved 1 August 2008.

- Beatrice Siu (4 August 2008). "Street protester Regina says scrap the levy". The Standard. Hong Kong. Archived from the original on 22 May 2011. Retrieved 7 August 2008.

- Bonnie Chen (17 July 2008). "HK$11b on table to ease inflation pain". The Standard. Hong Kong. Archived from the original on 11 December 2008. Retrieved 1 August 2008.

- 港府拟"派糖"近50亿纾民困 部分周内或通过拨款. China News (in Chinese). 16 July 2008. Retrieved 7 August 2008.

- Beatrice Siu (18 July 2008). "Waiver leaves maids in limbo". The Standard. Hong Kong. Archived from the original on 11 December 2008. Retrieved 31 July 2008.

- Beatrice Siu (23 July 2008). "Maids in legal threat over levy". The Standard. Hong Kong. Archived from the original on 22 May 2011. Retrieved 31 July 2008.

- Beatrice Siu (21 July 2008). "New hope for maids". The Standard. Hong Kong. Archived from the original on 11 December 2008. Retrieved 31 July 2008.

- Bonnie Chen & Beatrice Siu (31 July 2008). "Maids can stay put". The Standard. Hong Kong. Archived from the original on 11 December 2008. Retrieved 31 July 2008.

- Editorial (31 July 2008). "Time to end farcical levy on domestic helpers". South China Morning Post. Hong Kong. pp. A14.

- op-ed: Stephen Vines (25 July 2008). "Tsang shows again how to rule with a ham fist". South China Morning Post. Hong Kong.

- op-ed: Albert Cheng (26 July 2008). "The levy has burst". South China Morning Post. Hong Kong.

- Beatrice Siu (8 October 2008). "Maids aim to breach levy". The Standard. Hong Kong. Archived from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 9 October 2008.

- "Immigration Department gives out 2,180 passes". The Standard. Hong Kong. 1 August 2008. Archived from the original on 22 May 2011. Retrieved 1 August 2008.

- Eva Wu & Mary Ann Benitez (4 August 2008). "Regina Ip takes flak over Article 23 role". South China Morning Post. Hong Kong.

- Mary Ann Benitez & Austin Chiu (30 August 2008). "Freeze of maid levy spells profits for illegal queue touts". South China Morning Post. Hong Kong. p. C3.

- "Maid levy will not be scrapped". The Standard. Hong Kong. 22 October 2008. Archived from the original on 22 May 2011.

- Diana Lee (29 October 2008). "Ip move to scrap maid levy 'out of order'". The Standard. Hong Kong. Archived from the original on 22 May 2011.

- Bonnie Chen (3 November 2008). "Ip sticks to guns on scrapping maid levy". The Standard. Hong Kong. Archived from the original on 22 May 2011.

- Mary Ann Benitez (7 November 2008). "Maid levy opponents warn off minister". South China Morning Post. Hong Kong. p. C1.

- Beatrice Siu (12 November 2008). "Maid deal done and dusted". The Standard. Hong Kong.

- "Shadow Report to the United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination Regarding the Report of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China". Hong Kong Human Rights Monitor. July 2001. Archived from the original (RTF) on 28 August 2008. Retrieved 18 March 2007.

- "Exploited For Profit, Failed By Governments – Indonesian Migrant Domestic Workers Trafficked To Hong Kong". Amnesty International. 21 November 2013.

- "Hong Kong: Hundreds of Domestic Workers Abused by Employers". International Business Times UK. 20 January 2014.

- "Hong Kong". Amnesty International. 10 February 2015.

- "Campaigners protest over death of Indonesian maid in Hong Kong". Yahoo! News. 17 March 2015.

- "Protest at agency over maid slab death" Archived 11 June 2015 at the Wayback Machine. The Standard, 18 March 2015.

- "Topical Issues: Who can enjoy the Right of Abode in the HKSAR?". Immigration Department of HKSAR. 14 February 2007. Archived from the original on 15 March 2007. Retrieved 18 March 2007.

- "Topical Issues: Right of Abode and other related terms". Immigration Department of HKSAR. 14 February 2007. Archived from the original on 15 March 2007. Retrieved 18 March 2007.

- Chiu, Austin (22 August 2011). "Residency definition challenged" South China Morning Post

- Knowles, Caroline; Harper, Douglas (2009). Hong Kong. University of Chicago Press. doi:10.7208/chicago/9780226448589.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-226-44857-2.

- Yau, Cannix (1 March 2003). "Fighting to stay" Archived 12 June 2015 at the Wayback Machine. The Standard Retrieved 10 October 2011

- Mary Ann Benitez (20 August 2007). "Rough justice". South China Morning Post. Hong Kong. pp. A14.

- Jack Hewson. "Hong Kong's domestic worker abuse". Al Jazeera.

- Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, Concluding observations on the People's Republic of China (including Hong Kong and Macao), UN Doc. E/C.12/1/Add.107, 13 May 2005, para95.

- 457 Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women, Concluding comments on China, UN Doc. CEDAW/C/CHN/CO/6, 25 August 2006, para42.

- "Domestic helpers in Hong Kong must be protected from abuse". South China Morning Post. 16 January 2014.

- "Hong Kong couple jailed for torturing maid who was 'forced to wear diaper'". The Express Tribune. 23 September 2013.

- "Hong Kong couple jailed for torturing maid who was 'forced to wear diaper'". Reuters. 19 September 2013. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 1 July 2017.

- "This page has been removed". The Guardian.

- "A Primer for the United Filipinos in Hong Kong (UNIFIL-HK)". United Filipinos in Hong Kong (UNIFIL-HK). Archived from the original on 6 February 2007. Retrieved 18 March 2007.

- "HK maids protest new Philippine labor law". The Manila Times. 5 February 2007. Archived from the original on 5 July 2007. Retrieved 18 March 2007.

- Constable, Nicole. “Migrant Workers and the Many States of Protest in Hong Kong.” Critical Asian Studies 41, no. 1 (March 1, 2009): 143–64

- Palmer, Wayne (1 May 2013). "Public–private partnerships in the administration and control of Indonesian temporary migrant labour in Hong Kong". Political Geography. 34: 1–9. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2013.02.001.

- Legislative Council Panel on Manpower, "Intermediary Charges for Foreign Domestic Helpers", LC Paper No. CB(2)1356/12-13(03), 18 June 2013, para11. Retrieved 8 October 2013.

- "Erwiana's court victory – now to step up the struggle for migrant rights!". China Worker.

- "Hong Kong domestic helpers arrested in crackdown on 'live-out' maids". South China Morning Post, 28 January 2015 (subscription required)

- "HK Labor Department probes abuse of Filipino migrant worker". Rappler. 17 May 2014.

- "Hong Kong drops 'discriminatory' vaccine plan for foreign workers". www.aljazeera.com. 11 May 2021. Retrieved 8 August 2021.

Further reading

- Constable, Nicole (4 October 1996). "Jealousy, Chastity, and Abuse: Chinese Maids and Foreign Helpers in Hong Kong". Modern China. 22 (4): 448–479. doi:10.1177/009770049602200404. S2CID 145159375.

External links

- Hong Kong Domestic Helpers Campaign

- Helpers for Domestic Helpers

- United Filipinos in Hong Kong (UNIFIL-HK)

- "Where Filipinas Hold Up Half the Colony". Philippine News. 3 January 2007. Archived from the original on 14 February 2007. Retrieved 26 January 2007.