Food deserts by country

This is a list of food desert issues and solutions by country.

Africa

African food deserts are complex due to accelerated urbanization, the various ways individuals acquire food through formal and informal food economy markets, familial dynamics of the household, and African social, political and economic effects.[1] African food deserts have been defined as "poor, often informal, urban neighborhoods characterized by high food insecurity and low dietary diversity, with multiple markets and market and non-market food sources but variable household access to food."[1]

The definition of a food desert often relates to the distance between residents and the nearest supermarket. In Western nations, supermarkets prevail over traders and vendors but food sourcing methods within Africa are reversed. Certain regions have an informal economy where traders and vendors are available within the areas they live and other local areas.[1] Urban agriculture also plays a big role within Africa as pastoralism is widely practiced – populations raise their own livestock and grow their own food creating informal rural-urban food transfer systems. These practices vary throughout Africa but do not increase food security and limits community resources to create a food desert.[2] Low-income populations are still more inclined to source food in these ways, however supermarket growth in both urban and rural areas is cutting off these food sourcing methods and worsening food security.[3]

Accordingly, households within the same food desert source food differently.[1] Most neighborhoods have a mix of various income levels. Those with higher incomes have better access to transportation and are more likely to shop at the nearest grocery store. Lower income households tend to stick to sourcing food from local vendors with more limited operating hours or through pastoralism.[3] The African Food Security Urban Network (AFSUN) found that nearly 70% of poor urban African households sourced part of their food needs from vendors and traders and 79% of these households utilized a supermarket. When these studies took frequency into account, it was found that poor Africans use informal vendors more often for most of their needs and go to supermarkets to buy large quantities of a staple.[1]

With economic growth contributing to the building of supermarkets and other urban renewal practices, land space is taken from pastoral communities that grow and harvest their own food and reduces the resources vendors use to attain the products they sell, limiting their business practices and giving rise to food deserts in Africa.[3] Modern food systems in towns and cities are coming about rapidly changing and destabilizing the already high food insecurity practices already in place.

The AFSUN survey results indicate a wide variety of factors, such as gender, income, and education affect access to nutritious food.[1] Households headed by a man have greater access to food than those headed by a woman.[1] This is due to various socio-political towards women that do not affect modern, Western women who have more access to financial opportunities. In Africa, female heads of households are twice as likely to be food insecure than men. Women have less mobility within Africa and thus rely more on less secure food sourcing practices.

Transportation problems

African cities suffer from a large degree of fragmentation which leads to the poor having to utilize public transportation to travel large distances, spending up to 3 hours a day in transit. With much of the day wasted in transit, poor Africans have less time to spend on shopping or preparing food which forces them to buy more expensive, less nutritious, already prepared foods from either street vendors or restaurants.[3] This fragmentation and mobility also leads to many poor Africans shopping for groceries in places outside their township. A study in Soweto, Johannesburg in 2004 showed most urban poor spend about 50% of their expenses in places outside of the towns in which they reside.[1]

Impacts

The 1995 Income and Expenditure Survey conducted in South Africa assessed an urban food insecurity rate of 27 percent, relative to the rural rate of 62 percent.[4] Later studies such as the National Food Consumption Survey of 1999[5] and South African Social Attitudes Survey of 2008 independently assessed the urban food insecurity rate to be roughly half of that of the rural rate.[6]

A 2000 survey conducted on rural Eastern Cape, rural Western Cape and urban Cape Town assessed food insecurity to be 83, 69, and 81 percent, respectively. This survey took into account other urban African factors than distribute the tendency of residents to utilize formal food sources over informal like agriculture and local markets.[3]

Australia

Socioeconomic Disparities

In Australia, jobs are organized into low or high class using Australian and New Zealand Standard Classification of Occupations (ANZSCO) which considers skills, education, and experience to place the job. The location of food deserts are often into areas where people's jobs and income are considered on the low side of the spectrum.[7] In Western Australia, a dearth of high quality and affordable fruit and vegetables in isolated regions was identified as one factor limiting consumption, along with produce seasonality.[8] A 2014 review found that the less populous and very remote areas of the state had fewer grocery stores and higher prices for fruit, vegetables, and dairy than in cities. Economically it is reported that in areas with low income, families would have to spend 56% of their income on buying healthy food. Lack of availability to fresher food leads to unhealthy food consumption resulting in what is described as a "obesogenic" neighborhood, which simply means that the environment's food surroundings do not support healthy eating.[7] Of these stores, 20% did not generally supply produce that met all quality standards with a few exceptions, unlike urban areas with exceptions for lettuce and green beans in Perth.[9] Geographical data were not analyzed for prevalence of low income residents to define areas as food deserts.

Effects

A five-year campaign to increase access to healthy foods started in 1990 and led by the Department of Health in Western Australia and industry groups had mixed success.[8] By also creating community programs that provide food and transport services to families that live within a 1,600 meter radius of a grocery store. And also focusing on prevention of diabetes and diabetes management.[10] The minor health effects that can come from not having sustainable food options can be childhood obesity and even health issues like asthma. Although long-term health effects can come from the minor health problems like heart disease caused from the obesity and type 2 diabetes. And if these bad habits continue unchanged a person effected by these disease could die prematurely.[11] The department later developed a new private/public partnership to address access and consumption of fruit and vegetables.[12] A 2008 audit found some progress generated as a result in incentive's fruit and vegetable access, but no headway in identifying and addressing any supply issues in development planning or elucidating cost, quality and access issues for remote, rural and urban areas.[12]

Europe

"European (non-UK) food access research also frequently highlights the problem of poverty in relation to accessing a healthy diet." French researches have noted that lower income consumers have a tendency to reach for more affordable items such as high caloric foods, (i.e. cereals, sweets, and added fats) instead of nutrient rich single source foods.[13]

United Kingdom

British food deserts can be broadly classified into twelve geographical types, based on the interaction of socioeconomic factors of physical access to shops, financial access (affordability of) healthy food, and attitudes towards consumption of healthy food, the desire to consume it rather than fast / convenience food, possession of cooking skills, that is, psychological access.

These twelve neighbourhood types are:

- Inner city executive flat areas (too fast lifestyle to cook healthily),

- Inner city ethnic minority areas (cost of food vs low wages),

- Inner city deprived areas severed by main roads from retail areas (poor physical access),

- Declining suburban areas (shops closing, poor physical access to supermarkets),

- Planned local authority housing areas (low income, and shops often lack fresh produce),

- Student residence areas (preference for fast food outlets, little demand for fresh produce),

- Wealthy suburban areas, most shop by car, but some less mobile pensioners with no car.

- Small market town centres losing trade to out-of-town supermarkets, leaving the car-less without easy access,

- Market town suburbs, poor bus service to centre perhaps 1 or 2 miles (2 – 3 kilometres) distant,

- Smaller rural towns, lack full range of fresh produce,

- Remoter villages, no shop, and under-served by mobile shops,

- Dispersed settlements, no focal point for shop.[14]

Areas 8 – 12 are rural food deserts.

Furey et al. describes food desert creation as arising where "high competition from large chain supermarkets has created a void".[15]

North America

United States

.jpg.webp)

Implications

Food deserts are defined by a shortage of supermarkets and other stores that carry affordable healthful food.[16] Audit research suggests that supermarkets are the most effective way to supply communities with a wide selection of fresh and relatively affordable healthful food. Moreover, they are typically open year-round, provide convenient hours of operation and generally accept food stamps from the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC).[17] Small-scale, full-service food markets could play a role in increasing community food security.[18]

Affordability

Compared to residents of higher-income neighborhoods, low socioeconomic status (SES) individuals tend to have diets higher in meat and processed foods and a lower intake of fruits and vegetables.[19] They are more likely to purchase inexpensive fats and sugars over fresh fruits and vegetables that are more expensive on a per calorie basis.[20][21] On average, the most energy-dense foods only cost $1.76 per 1,000 calories, compared to $18.16 per 1,000 calories for low-energy nutritious foods.[22] This is one reason cited for why low-income populations and minorities are more predisposed to suffer from obesity, diabetes and cardiovascular disease.[23]

Income may play a big role in determining the eating habits of families in food deserts.[24] Those impacted by food deserts are typically impoverished,[25] with an average income between $5,000 and $20,000 annually.[26] According to the USDA, "Research that considers the prices paid for the same food across household income levels indicates that while some of the very poorest households—those earning less than $8,000 per year—may pay between 0.5 percent and 1.3 percent more for their groceries than households earning slightly more, households earning between $8,000 and $30,000 tend to pay the lowest prices for groceries, whereas higher income households pay significantly higher prices."[27]

Chain supermarkets benefit from economies of scale to offer consumers low prices, but are less prevalent in low-income urban areas. In the United States, the number of supermarkets in low income neighborhoods is approximately 30% less than in the highest-income neighborhoods.[28] Within cities, three times as many supermarkets are in wealthier neighborhoods than poorer ones.[19] "Economies of scale, which is when the costs of operating a store decrease as store size increases, and economies of scope, which is when the costs decrease as more product variety increases, suggests that larger stores that offer greater variety can do so and offer lower prices. Both factors may account for the ability of larger stores to survive more easily than smaller stores."[29] A 2008 book noted that 22% of the chain supermarkets in Minneapolis were located in the inner city compared to more than 50% of the non-chain stores.[30] In the end, a 1990 U.S. government report found that people in urban areas pay 3 to 37 percent more for the same groceries locally than they would in a suburban supermarket.[31]

In the absence of other grocery outlets, residents in low-income urban areas are often "forced to depend on small stores with limited selections of foods at substantially higher prices".[32] Fringe food retailers have market power to increase prices (around 30-60%) off a limited product selection dominated by processed foods.[29] Research finds "retail prices for the same foods to be higher in deprived areas" that have a dearth of supermarkets and food stores. Findings from the USDA support that prices for similar goods are on average higher at convenience stores than at supermarkets.[16] As a result, people of low SES ultimately spend up to 37% more on their food purchases.[32]

Smaller communities have fewer choices in food retailers. Resident small grocers struggle to be profitable partly due to low sales numbers, which make it difficult to meet wholesale food suppliers' minimum purchasing requirements.[33] The lack of competition and sales volume can result in higher food costs.[34][33] For example, in New Mexico the same basket of groceries that cost rural residents $85, cost urban residents only $55.[35] However, this is not true for all rural areas. A study in Iowa showed that grocers in four rural counties had lower costs on key foods that make up a nutritionally balanced diet than did larger supermarkets outside these food deserts (greater than 20 miles away).[36]

Grocery stores in low income communities have less variety.[23] Small rural grocers and stores in areas where consumers are less interested in buying produce will carry less fruits and vegetables because they are more expensive compared to processed foods, especially in food deserts. This relates to the problem of "food swamps", regions that lack healthy and nutritious food choices.[37] Even when healthy foods are available, they may not be affordable for many residents in poorer communities.[38] Higher prices on healthy food than unhealthy potentially affects obesity rates.[39]

In a study on urban food environments, participants described the lack of supermarkets as a "practical impediment to healthful food purchase and a symbol of their neighborhoods' social and economic struggles".[40]

Health outcomes

There are diet and health implications for those who live in areas where nutritious food is not readily available; some claims, such as linking food deserts with obesity in children, are disputed.[20][21][41]

A summary report by The Colorado Health Foundation concluded that individuals with access to supermarkets tend to have healthier diets and a lower risk of chronic disease such as diabetes.[42] Food deserts are correlated with many poor health outcomes. Other studies find a link between better access to supermarkets and lowered risk of obesity. As well, better access to convenience stores is associated with a higher risk of obesity.[16]

- A lack of plant-based foods (fruits, vegetables, nuts, whole grains) correlates with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease.[16]

- Beverages sweetened with sugar are linked to a higher risk of obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease.[16]

- Studies on food deserts and type 2 diabetes mellitus demonstrate that areas with limited access to nutritious food are associated with an increased prevalence of type 2 diabetes .[43][44][45]

Studies show that food insecurity can impact the health of elderly adults including lower BMI, limited activity and malnutrition.[46] An elderly person without consistent access to enough fruits and vegetables and the proper variety of nutrients are at higher risk for health problems and future ailments.[47]

A 2010 study inversely correlated distance from supermarkets and decreased availability of healthy foods with increases in body mass index and risk of obesity.[48] Among elderly people in particular, malnutrition caused by inadequate access to food can lead to other health risks. For those suffering from weight loss and undernutrition, risks include increased and longer hospitalizations, early admission to long-term care facilities, and overall increased morbidity and mortality.[49] Nutritional disorders with co-morbidities are the ninth most frequent diagnostic category among hospitalized rural elderly Medicare beneficiaries. Elderly adults struggling with obesity and overnutrition related to limited food choices are at risk of exacerbating existing chronic conditions, such as heart disease and diabetes, and increased functional decline.[49][50]

While correlations have been found, the causal pathways are complex and not fully understood. Most studies on food environments and health are cross-sectional and thus cannot make causal conclusions. Improvements in research are needed before causal relationships can be explicitly defined.[16]

Transportation barriers to food access

According to 2010 reports from the USDA, approximately 29.7 million people (9.7% of the population) live in low-income areas that are more than 1 mile from a supermarket.[16] Often the only close places for residents to purchase food are convenience stores or corner shops.[51] A 2005 study utilizing GIS determined that among the most impoverished neighborhoods in Detroit, African American ones were on average 1.1 miles farther from the nearest supermarket than white ones and 28% of their residents did not own a car.[52]

Urban areas usually have private and public transportation such as buses and trains available, but rural areas typically offer little to no public transportation even though the grocery stores are far from home.[23]

According to The Reinvestment Fund (TRF) and Low Supermarket Access areas (TRF 2012), the density of car ownerships is much lower in poorer communities.[53] Accessing healthy foods then becomes more difficult without reliable transportation. The Food Access Research Atlas (ERS 2013) maps out the measurement of food access in both low- and high-income communities. Under this measure, they point out the significance of number of cars within and a number of supermarkets in the area.[53]

And so, many people in low-income neighborhoods may spend more on transportation to bring their groceries home. The Colorado Health Foundation found that taxi cab drivers make more trips to grocery stores at the beginning of the month when food stamps are distributed and at the end of the month before they expire.[42] Fortunately, vehicle availability has improved over the past couple of decades has been helping disadvantaged residents overcome economic barriers and food access barriers in both rural and urban food deserts.[25]

As of 2007, the elderly made up 7.5 million of the 50 million people living in rural America.[54] The U.S Census website includes maps showing the percentage of residents aged 65 and older.[55] Of these elderly citizens, nearly a half million live in rural food deserts and are food insecure, while many more may be at risk. A study by Sharkey, et al. from seniors in the Brazos Valley showed that 14% couldn't make their monthly allotment of food supplies last, 13% couldn't eat balanced meals and 8.3% had to make their meals smaller or skip them.[56]

Elders are particularly affected by the obstacle of distance presented by rural food deserts. A survey by the interest group and insurer AARP reported that at age 75 and older, 83% of men and 60% of women still drive, down from 93% and 84% respectively at age 65 and lower than the 78% and 80% of the next lowest group, 16-24 year-olds.[57] A lack of decent public transportation services in rural areas can therefore make it harder for elderly to shop.[58] As a result, it is 9.6% more probable that elders without a car living in a food desert will skip meals than those with one.[46] Because of their lack of access to vehicles, older people are more likely to be dependent on those in their community to get food.[59]

Racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic disparities

Health disparities related to food access and consumption are associated with residential segregation, low incomes, and neighborhood deprivation. Morland et al. found that areas with a majority of convenience stores had a higher prevalence of overweight and obese individuals compared to areas with only supermarkets.[32] A lack of adequate food sources and limited transportation available to low-income communities may contribute to poor nutrition.[32]

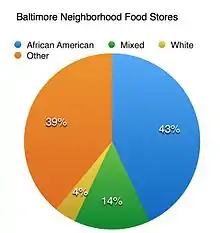

Research has documented differences in supermarket access between poor and non-poor urban areas. Baker et al. found that mixed-race areas were significantly less likely to have access to foods that adhere to a healthful diet compared to predominantly white, high income areas.[41] Research by Mari Gallagher found African Americans to be farther from healthful foods than other racial groups.[60][61][62] Supermarkets in African American neighborhoods are just 52% as prevalent as in white neighborhoods.[63] Moreover, a review of food-frequency data in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study revealed that dominantly white populations had five times more supermarkets than neighborhoods that were dominantly non-white.[64] African Americans who lived in the same census tract with supermarket access were more likely to meet dietary guidelines for fruit and vegetable consumption. Each additional supermarket increased fruit and vegetable intake by 32%.[64]

A 2010 study analyzed data from the Centers for Disease Control and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services to assess the health outcomes of women participating in SNAP and the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program.[65] The study primarily critically assessed the structure of current social welfare policies, but noted that 25% of food stamp program participants lack easy access to a supermarket.

A 2008 report claimed that in the Chicago metropolitan area, African-American neighborhoods lack independent and chain supermarkets unlike Hispanic communities, although none are full-service chains. However, between 2005 and 2007, more discount stores did move into African-American communities.[66] Hispanic communities in food deserts have targeted Hispanic food markets.[67]

Transportation initiatives

The USDA released an extensive report to Congress in 2009 as a request to reform the Food, Conservation, and Energy Act of 2008. Study recommendations for addressing access issues in food deserts included the above options as well as transportation reforms.[33] Where growing vehicle availability is insufficient, better public transportation in rural food deserts or promoting safe walking and biking environments in urban areas may help.[25][36] Proposed solutions include utilizing a combination of public and private resources.[36] Current transit assistance and meal-provisioning programs that are already established in many communities, such Meals on Wheels, have initiatives that focus on providing food residents with limited mobility and ability to shop at traditional food retailers.[68]

Incentivizing supermarket and grocery store number

State and local governments are implementing public-private partnerships that use a combination of financing initiatives and community-level interventions to target areas with lower healthy food access.[33] The progenitor program was Pennsylvania's Fresh Food Financing Initiative, a public-private partnership started in 2004 with state seed funds.[69][70] Success of the initiative led to the creation of similar programs in at least seven states and cities, like the New York City Food Retail Expansion to Support Health (FRESH) program.[70] In early 2010 the Obama administration unveiled the related Healthy Food Financing Initiative.[71]

Universities have coordinated with local business and community leaders to solve food scarcity issues. In 2008, La Salle University and The Fresh Grocer teamed up to open a grocery store in Germantown, Philadelphia. The Germantown neighborhood was plagued with a decades-long food desert, but thanks to a coordination between two enterprises, the Fresh Grocer was able to provide more than 250 jobs to Philadelphians and provide healthy food.[72][73]

Community/family help

Families often work together and develop a network of sharing[74][75][76] to exchange clothing, provide childcare, sell personal possessions, and share transportation resources and even housing. People living in food deserts often use this approach to feed their families.[74][75]

Foodsheds

Foodshed planning is an integral part of policy for not only New York, but other cities such as Chicago, Toronto and Cincinnati. [77] Columbia University's 2010 New York City Regional Foodshed Initiative set out to analyze local food production capacity of the Metropolitan Region as part of a strategy to increase availability of affordable, healthful food in all neighborhoods.[78] Some projects increase the availability of healthy affordable food by establishing community-run markets, farmers markets, mobile grocery carts or stores, and urban agriculture projects.[33]

Farmers' markets

Some food movements hold that locally grown food at farmers' markets is superior to that typically in supermarkets.[79] However, these markets are often too costly for the budget-conscious.[63] Government programs like SNAP and WIC often in partnership with nonprofit organizations subsidize low-income individuals to purchase produce from farmers' markets.[80][79]

In rural Bertie County, the poorest county in North Carolina, community members in conjunction with a public high school class designed and constructed a pavilion to serve as a home for a local farmers' market.[81]

Community gardens

Community involvement and the incorporation of local organizations and volunteerism can improve the effectiveness of food safety nets and alternative solutions such as community gardens (e.g., see Urban agriculture in West Oakland).[34]

Internet stores

Internet delivery options overcome distance barriers in food deserts with meal kit services and online shopping for fresh groceries from retailers and food cooperatives.

State and federal agencies in New York created a program to allow food stamp recipients the option to purchase healthful foods online for home delivery. In the fall of 2016 this pilot program was launched in conjunction with an established food delivery company, FreshDirect, for two zip codes in the Bronx. The hope is that online food delivery can eliminate food deserts.[82][83]

Education

Research suggests that food deserts are not the real problem, eating habits are.[84] Indeed, one study found that 89.3% of people in a community were either "highly interested" or "interested" in education on preparing healthier food options.[85] Avenues to increase education and outreach about diet and health by the federal government include [23] the SNAP Education (SNAP-Ed) and Expanded Food and Nutrition Education Program (EFNEP).

See also

References

- Battersby, Jane; Crush, Jonathan (2014). "Africa's Urban Food Deserts". Urban Forum. 25 (2): 143–51. doi:10.1007/s12132-014-9225-5. S2CID 55960422.

- Crush, Jonathan; Frayne, Bruce; Pendleton, Wade (2012). "The Crisis of Food Insecurity in African Cities". Journal of Hunger & Environmental Nutrition. 7 (2–3): 271–92. doi:10.1080/19320248.2012.702448. S2CID 55269594.

- Battersby, Jane (2012). "Beyond the Food Desert: Finding Ways to Speak About Urban Food Security in South Africa". Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography. 94 (2): 141–59. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0467.2012.00401.x. S2CID 55452849.

- Central Statistical Service. "Income and Expenditure Survey 1995." DataFirst. N.p., 25 Oct. 2012. Web. 10 Nov. 2016. https://www.datafirst.uct.ac.za/dataportal/index.php/catalog/264

- Labadarios, D; Steyn, NP; Maunder, E; MacIntryre, U; Gericke, G; Swart, R; Huskisson, J; Dannhauser, A; Vorster, HH; Nesmvuni, AE; Nel, JH (2007). "The National Food Consumption Survey (NFCS): South Africa, 1999" (PDF). Public Health Nutrition. 8 (5): 533–543. doi:10.1079/PHN2005816. PMID 16153334. S2CID 10409376.

- Human Sciences Research Council. "South African Social Attitudes Survey 2008." DataFirst. N.p., 1 July 2014. Web. 10 Nov. 2016. https://www.datafirst.uct.ac.za/dataportal/index.php/catalog/488

- Zarnowiecki, Dorota (May 2017). "Socioeconomic Disparities in Food Consumption and Availability". Nutridate. 28 (2): 9–15.

- Miller, Margaret; Pollard, Christina (2005). "Health working with Industry to promote fruit and vegetables: a case study of the Western Australian Fruit and Vegetable Campaign with reflection on effectiveness and inter-sectoral action". Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health. 29 (2): 176–182. doi:10.1111/j.1467-842X.2005.tb00070.x. PMID 15915624. S2CID 27844278.

- Pollard, Christina M; Landrigan, Timothy J; Ellies, Pernilla L; Kerr, Deborah A; Lester, Matthew L; Goodchild, Stanley E (2014). "Geographic factors as determinants of food security: a Western Australian food pricing and quality study". Asia Pacific Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 23 (4): 703–713. doi:10.6133/apjcn.2014.23.4.12. PMID 25516329.

- "Dragging the chain on making a difference". The Sydney Morning Herald. 2018. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

- "Experts Identify Australia's Fresh Food Dead Zones with Big Health Problems". October 2018.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Pollard, Christina M; Lewis, Janette M; Binns, Colin W (2008). "Selecting interventions to promote fruit and vegetable consumption: From policy to action, a planning framework case study in Western Australia". Australia and New Zealand Health Policy. 5: 27. doi:10.1186/1743-8462-5-27. PMC 2621230. PMID 19108736.

- Shaw, Hillary (2012). "Access to healthy food in Nantes, France". British Food Journal. 114 (2): 224–38. doi:10.1108/00070701211202403.

- (Shaw H, The Consuming Geographies of Food: Diet, Food Deserts and Obesity, 2014, Routledge, 2014, pp. 132–133), see also http://www.fooddeserts.org

- Furey, Sinéad; Strugnell, Christopher; McIlveen, Heather (2001). "An investigation of the potential existence of 'food deserts' in rural and urban areas of Northern Ireland". Agriculture and Human Values. 18 (4): 447–457. doi:10.1023/A:1015218502547. S2CID 153287021.

- "Access to Affordable and Nutritious Food: Measuring and Understanding Food Deserts and Their Consequences" (PDF). United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service. Jun 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 November 2016. Retrieved 13 Nov 2016.

- Neckerman, K. M., Bader, M., Purciel, M., & Yousefzadeh, P. (2009). Measuring Food Access in Urban Areas. Built Environment and Health . Neighborhood Revitalization. (2011). Retrieved 3 10, 2011, from The District of Columbia:

- Short, Anne & Guthman, Julie & Raskin, Samuel. 2007. Food Deserts, Oases, or Mirages? Small Markets and Community Food Security in the San Francisco Bay Area. Journal of Planning and Education Research 2007, 26:352.

- Ming-Chen Yeh and David L. Katz. "Food, Nutrition, and the Health of Urban Populations". In Cities and the Health of the Public (Nicholas Freudenberg, Sandro Galea, and David Vlahov, eds.). Vanderbilt University Press (2006), pp. 106-127. ISBN 0-8265-1512-6.

- Story, Mary; Kaphingst, Karen M.; Robinson-o'Brien, Ramona; Glanz, Karen (2008). "Creating Healthy Food and Eating Environments: Policy and Environmental Approaches". Annual Review of Public Health. 29: 253–72. doi:10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.020907.090926. PMID 18031223.

- Kolata, Gina (17 April 2012). "Studies Question the Pairing of Food Deserts and Obesity". The New York Times.

- Monsivais, Pablo; Drewnowski, Adam (2007). "The Rising Cost of Low-Energy-Density Foods". Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 107 (12): 2071–6. doi:10.1016/j.jada.2007.09.009. PMID 18060892.

- "Food Deserts". Cotati, CA: Food Empowerment Project. Retrieved July 14, 2017.

- Cortright, Joe. "Are Food Deserts to Blame for America's Poor Eating Habits?". The Atlantic. Retrieved 2017-05-16.

- Dutko, P. (Fall 2012). "Food Deserts Suffer Persistent Socioeconomic Disadvantage". Choices. 27 (3): 1–4.

- Dubowitz, Tamara; Zenk, Shannon N.; Ghosh-Dastidar, Bonnie; Cohen, Deborah A.; Beckman, Robin; Hunter, Gerald; Steiner, Elizabeth D.; Collins, Rebecca L. (August 2015). "Healthy food access for urban food desert residents: examination of the food environment, food purchasing practices, diet and BMI". Public Health Nutrition. 18 (12): 2220–2230. doi:10.1017/s1368980014002742. PMC 4457716. PMID 25475559.

- Access to affordable and nutritious food: Measuring and understanding food deserts and their consequences: Report to Congress. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. Jun 2009. Web. 10 Nov 2016.

- Chung, Chanjin; Myers, Samuel L. (1999). "Do the Poor Pay More for Food? An Analysis of Grocery Store Availability and Food Price Disparities". Journal of Consumer Affairs. 33 (2): 276–96. doi:10.1111/j.1745-6606.1999.tb00071.x. JSTOR 23859959. S2CID 154911489. SSRN 2026583.

- Haider, Steven J.; Bitler, Marianne (March 2009). An Economic View of Food Deserts in the United States (PDF). Understanding the Economic Concepts and Characteristics of Food Access. National Poverty Center. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2017-07-28.

- Winne, M. (2008). Closing the Food Gap: Resetting the Table in the Land of Plenty. Beacon Press.

- Morland, Kimberly; Wing, Steve (2007). "7. Food Justice and Health in Communities of Color". In Bullard, Robert D. (ed.). Growing Smarter: Achieving Livable Communities, Environmental Justice, and Regional Equity. Urban and Industrial Environments. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press. p. 173. ISBN 978-0262524704.

- Morland, Kimberly; Wing, Steve; Diez Roux, Ana; Poole, Charles (2002). "Neighborhood characteristics associated with the location of food stores and food service places". American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 22 (1): 23–9. doi:10.1016/s0749-3797(01)00403-2. hdl:2027.42/56186. PMID 11777675.

- Ver Ploeg, Michele (2009). Access to Affordable and Nutritious Food: Measuring and Understanding Food Deserts and Their Consequences: Report to Congress. DIANE Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4379-2134-2.

- Smith, Chery; Morton, Lois W. (2009). "Rural Food Deserts: Low-income Perspectives on Food Access in Minnesota and Iowa". Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior. 41 (3): 176–87. doi:10.1016/j.jneb.2008.06.008. PMID 19411051.

- Treuhaft, Sarah; Karpyn, Allison (2010). "The Grocery Gap" (PDF). PolicyLink.

- Morton, Lois Wright; Blanchard, Troy C. (2007). "Starved for access: life in rural America's food deserts" (PDF). Rural Realities. Rural Sociological Society. 1 (4): 1–10. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-10-21. Retrieved 2017-07-28.

- Hui Luan; Jane Law; Matthew Quick (2015). "Identifying food deserts and swamps based on relative healthy food access: a spatio-temporal Bayesian approach". International Journal of Health Geographics. 14: 37. doi:10.1186/s12942-015-0030-8. PMC 4696295. PMID 26714645.

- "Measuring the Food Environment in Canada". Food and Nutrition. Health Canada. 11 Oct 2013. Retrieved 13 Nov 2016.

- Ghosh-Dastidar, B.; Cohen, D.; Hunter, G.; Zenk, S. N.; Huang, C.; Beckman, R.; Dubowitz, T. (2014). "Distance to store, food prices, and obesity in urban food deserts". American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 47 (5): 587–595. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2014.07.005. PMC 4205193. PMID 25217097.

- Cannuscio, Carolyn C.; Weiss, Eve E.; Asch, David A. (2010). "The Contribution of Urban Foodways to Health Disparities". Journal of Urban Health. 87 (3): 381–93. doi:10.1007/s11524-010-9441-9. PMC 2871079. PMID 20354910.

- Ford, Paula B; Dzewaltowski, David A (2008). "Disparities in obesity prevalence due to variation in the retail food environment: Three testable hypotheses". Nutrition Reviews. 66 (4): 216–28. doi:10.1111/j.1753-4887.2008.00026.x. PMID 18366535.

- Beck, Christina (2010). "Food Access in Colorado" (PDF). Colorado Health Foundation, Denver, Colorado.

- Fitzgerald N, Hromi-Fiedler A, Segura-Perez S, Perez-Escamilla R. Food insecurity is related to increased risk of type 2 diabetes among Latinas. Ethn Dis. 2011;21(3):328–34.

- Seligman HK, Bindman AB, Vittinghoff E, Kanaya AM, Kushel MB. Food insecurity is associated with diabetes mellitus: results from the National Health Examination and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 1999–2002. J Gen Intern Med 2007;22:1018–1023

- Gucciardi E, Vogt JA, DeMelo M, Stewart DE. Exploration of the relationship between household food insecurity and diabetes in Canada. Diabetes Care. 2009 Dec; 32(12):2218-24

- Fitzpatrick, Katie; Greenhalgh-Stanley, Nadia; Ver Ploeg, Michele (2016). "The Impact of Food Deserts on Food Insufficiency and SNAP Participation among the Elderly". American Journal of Agricultural Economics. 98: 19–40. doi:10.1093/ajae/aav044. S2CID 153437656.

- Nicklett, Emily J.; Kadell, Andria R. (2013). "Fruit and vegetable intake among older adults: A scoping review". Maturitas. 75 (4): 305–12. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2013.05.005. PMC 3713183. PMID 23769545.

- "Review: Research on Availability of Healthy Food in Food Deserts. Web-based document at DataHaven with summary of numerous recent studies on food desert impacts on health". DataHaven. 2011-01-31. Retrieved 2011-02-01.

- Thompson Martin, C.; Kayser-Jones, J.; Stotts, N.; Porter, C.; Froelicher, E. S. (2006). "Nutritional Risk and Low Weight in Community-Living Older Adults: A Review of the Literature (1995–2005)". The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 61 (9): 927–34. doi:10.1093/gerona/61.9.927. PMID 16960023.

- Jensen, Gordon L.; Friedmann, Janet M. (2002). "Obesity is Associated with Functional Decline in Community-Dwelling Rural Older Persons". Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 50 (5): 918–23. doi:10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50220.x. PMID 12028181. S2CID 22584096.

- "Access to Healthy Foods and Lower Prices Matter". www.nytimes.com. Retrieved 2023-03-03.

- Zenk, Shannon N.; Schulz, Amy J.; Israel, Barbara A.; James, Sherman A.; Bao, Shuming; Wilson, Mark L. (2005). "Neighborhood Racial Composition, Neighborhood Poverty, and the Spatial Accessibility of Supermarkets in Metropolitan Detroit". American Journal of Public Health. 95 (4): 660–7. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2004.042150. PMC 1449238. PMID 15798127.

- Ver Ploeg, M.; Dutko, P.; Breneman, V. (2014). "Measuring Food Access and Food Deserts for Policy Purposes". Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy. 37 (2): 205–25. doi:10.1093/aepp/ppu035.

- Rural Health Information Hub. (2018). "Rural Aging".

- CensusScope. (2011). [Map illustration of percentage of Americans 65+]. Demographic Maps: An Aging Population. Retrieved from http://www.censusscope.org/us/map_65plus.html

- Sharkey, Joseph R; Johnson, Cassandra M; Dean, Wesley R (2010). "Food Access and Perceptions of the Community and Household Food Environment as Correlates of Fruit and Vegetable Intake among Rural Seniors". BMC Geriatrics. 10: 32. doi:10.1186/1471-2318-10-32. PMC 2892496. PMID 20525208.

- Lynott, Jana; Figueiredo, Carlos (2011). "How the Travel Patterns of Older Adults Are Changing: Highlights from the 2009 National Household Travel Survey". AARP Public Policy Institute, Washington, D.C. p. 4.

- "Improve Access to Nutritious Food in Rural Areas". www.sog.unc.edu. Retrieved 2016-11-12.

- Bitto, Ella Annette; Morton, Lois Wright; Oakland, Mary Jan; Sand, Mary (2003). "Grocery Store Access Patterns in Rural Food Deserts". Journal for the Study of Food and Society. 6 (2): 35–48. doi:10.2752/152897903786769616. S2CID 144158597.

- Examining the Impact of Food Deserts on Public Health in Chicago, Mari Gallagher Research & Consulting Group, 2006. Retrieved from http://www.marigallagher.com/projects/4/

- Examining the Impact of Food Deserts on Public Health in Detroit, Mari Gallagher Research & Consulting Group, 2007. Retrieved from http://www.marigallagher.com/projects/2/

- Women and Children Last (In the Food Desert), Mari Gallagher Research & Consulting Group, 2007

- Leone, A. F.; Rigby, S; Betterley, C; Park, S; Kurtz, H; Johnson, M. A.; Lee, J. S. (2011). "Store type and demographic influence on the availability and price of healthful foods, Leon County, Florida, 2008". Preventing Chronic Disease. 8 (6): A140. PMC 3221579. PMID 22005633.

- Morland, Kimberly; Diez Roux, Ana V.; Wing, Steve (2006). "Supermarkets, Other Food Stores, and Obesity". American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 30 (4): 333–9. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2005.11.003. hdl:2027.42/57754. PMID 16530621.

- Correll, Michael (2010). "Getting Fat on Government Cheese: The Connection Between Social Welfare Participation, Gender, and Obesity in America". Duke Journal of Gender Law & Policy. 18: 45–77. SSRN 1921920.

- Block, Daniel; Chavez, Noel; Birgen, Judy (June 2008). "Finding Food in Chicago and the Suburbs, A Report of the Northeastern Illinois Community Food Security Assessment to the Public" (PDF). Chicago, IL: Chicago State University Neighborhood Assistance Center. p. 34. Retrieved July 20, 2016.

- Illinois Advisory Committee to the United States Commission on Civil Rights (October 2011). "Food Deserts in Chicago" (PDF). Washington, DC: United States Commission on Civil Rights. p. 7.

- "The Rural Initiative". Meals on Wheels Association of America. 2011. Archived from the original on 2009-02-15. Retrieved 2011-12-03..

- Story, A; Manon, M; Treuhaft, S; Giang, T; Harries, C; McCoubrey, K (2010). "Policy solutions to the 'grocery gap'". Health Aff (Millwood). 29 (3): 473–480. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0740. PMID 20194989.

- Story, Caroline; Harries, Julia; Koprak, Candace; Weiss, Stephanie; Parker, Kathryn M; Karpyn, Allison (2014). "Moving From Policy to Implementation: A Methodology and Lessons Learned to Determine Eligibility for Healthy Food Financing Projects". J Public Health Manag Pract. 20 (5): 498–505. doi:10.1097/PHH.0000000000000061. PMC 4204010. PMID 24594793.

- "Obama Administration Details Healthy Food Financing Initiative (Archived copy)". U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. 2010. Archived from the original on 2013-08-01. Retrieved 2013-07-28.

- "La Salle University Fresh Grocer Opens Today – ProgressiveGrocer".

- "After 40 years, a supermarket E. Germantowners now have one in their neighborhood". Archived from the original on 2016-06-23. Retrieved 2016-06-26.

- Miranne, K. B. (1998). "Income Packaging as a Survival Strategy for Welfare Mothers". Affilia. 13 (2): 211–32. doi:10.1177/088610999801300206. S2CID 143531471.

- McInnis-Dittrich, K. (1995). "Women of the Shadows: Appalachian Women's Participation in the Informal Economy". Affilia. 10 (4): 398–412. doi:10.1177/088610999501000404. S2CID 144862812.

- Stack, Carol B (1975). All Our Kin. New York, NY: Harper. ISBN 978-0060904241.

- Cohen, Nevin; Freudenberg, Nicholas; Willingham, Craig (April 24, 2017). "Growing a Regional Food Shed in New York: Lessons from Chicago, Toronto and Cincinnati". New York, NY: City University of New York Urban Food Policy Institute. Retrieved July 20, 2017.

- Bonnelly, Vanessa Espaillat (January 28, 2010). "The New York City Regional Foodshed". New York, NY: Columbia University The Earth Institute Urban Design Lab. Retrieved July 20, 2017.

- Donovan, Jeanie; Madore, Amy; Randall, Megan; Vickery, Kate (2016). "Best Practices & Challenges for Farmers Market Incentive Programs: A Guide for Policymakers & Practitioners". The Graduate Journal of Food Studies. 1 (1).

- Ver Ploeg 2009, p. 107.

- Schwartz, Ariel (2011). "High school students build a farmer's market in a food desert". Fast Company.

- FoodStamps. "Use Your EBT to Shop for Groceries Online". www.foodstamps.org. Retrieved 2016-11-08.

- "FreshDirect – About EBT at FreshDirect". FreshDirect. Retrieved 2016-12-11.

- "Why it takes more than a grocery store to eliminate a 'food desert'". PBS NewsHour. Retrieved 2017-03-21.

- Braunstein, N.S.; Ewell, J.B.; Santos, C.; Palmer, A.M. (2011). "Community Food Assessment in an Urban Food Desert". Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 111 (9): A82. doi:10.1016/j.jada.2011.06.298.