Samoan Civil War

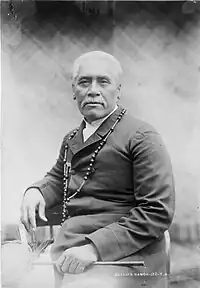

The turbulent decades of the late 19th century saw several conflicts between rival Samoan factions in the Samoan Islands of the South Pacific. The political struggle lasted roughly between 1886 and 1894, primarily between Samoans contesting whether Malietoa Laupepa, Mata'afa Iosefo, or a member of the Tupua Tamasese dynasty would be King of Samoa. While largely a political struggle, there were also armed skirmishes between the factions. The military of the German Empire intervened on several occasions. A naval standoff between the United States, Germany, and the United Kingdom ensued.

| Samoan conflicts of 1887–1889 and 1893–1894 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

1887–1889 Supporters of Mata'afa Supported by: |

1887–1889 Supporters of Tamasese | ||||||

|

1893–1894 Supporters of Mata'afa (1893) Supporters of Tamasese Lealofi (1894) |

1893–1894 Supporters of M. Laupepa Supported by: | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

Malietoa Laupepa ascended to the kingship in 1881. However, relations between him and the German Empire collapsed in 1885–1886, and the Germans arranged his exile from the Samoan Islands in 1887. In Laupepa's absence, the Germans supported Tamasese's claim to leadership while Mata'afa formed a rival government weakly supported by the United States. After the 1889 Apia cyclone destroyed six of the German and American ships stationed at Samoa, the three Western countries decided that the counterproductive fighting should cease, and that Laupepa would be restored to the kingship. The struggle resumed in 1893–1894. Laupepa maintained his position against the challengers of Mata'afa and the new Tamasese heir. Mata'afa was exiled and Tamasese's rebellion was quashed, restoring peace, albeit temporarily.

Background

The structure of Samoan leadership in the late 19th century was one where the role of Tafa'ifa, or King of Samoa, was contested. In general, a Tafa'ifa was expected to control the four or five most important paramount chieftainships. However, this role was weaker than European monarchies of the era: those who granted the chieftainships could revoke it at any time. This would be a source of tension and misunderstandings between the Western powers interested in Samoa and the Samoan leadership, as the Westerners assumed that the King held more power than they actually did.[2]

In 1880, King Malietoa Talavou Tonumaipeʻa died. His successor was his nephew Malietoa Laupepa; some skirmishes seem to have occurred from 1880–1881 as Laupepa attempted to secure his power. In March 1881, Laupepa was recognized as Tafa'ifa by the Western powers most commercially invested in Samoa: the German Empire, the United States, and the British Empire. But Laupepa's control was still incomplete: he held only two of the most important chieftain titles, not all four. Tupua Tamasese Titimaea was recognized as Tui-Aʻana, and Mata'afa Iosefo was Tui-Atua. Hostilities might have commenced in 1881, but an American warship, the USS Lackawanna, either imposed or negotiated a peace treaty, with the approval of the Western consuls. Under it Laupepa continued as king, and Tamasese as vice-king. This peace lasted four years.[3]

Captain Zembsch, the Imperial German Consul who had acquired a good reputation with the Samoans as someone willing to advocate for them even against his fellow countrymen running the plantations, was recalled in 1883. His replacement, Stuebel, was more directly loyal to the German Firm. Stuebel increased pressure on Laupepa, complaining of routine theft of food from the plantations, and demanding the right to imprison Samoans caught stealing in German-operated private jails. Laupepa eventually conceded to Stuebel's demands, but quietly contacted the British seeking aid to foil the new German demands. The Germans quickly got wind of this and soured on Laupepa; rumors of a German annexation flew through Samoa in 1885. The Germans attempted to convince vice-king Tamasese to act against Laupepa and provided him with arms; Tamasese declared his kingship at Leulumoega in Aʻana in January 1885, but did not immediately act against Laupepa, however. In late 1885, the Germans forced Laupepa out of his home, raised the German flag at Mulinu'u, and built a fort there. The Americans weakly supported Laupepa, but counseled patience and largely waited on replies from their distant home governments. The British were largely passive, and weakly favored the German position to the extent they opined at all. A new wild card entered the fray in January 1887: the prime minister of the Kingdom of Hawaii, the adventurer Walter M. Gibson, had deployed a "homemade battleship" Kaimiloa on a friendship tour across the South Pacific looking for an alliance against colonial powers. The Hawaiian embassy was greeted warmly and a treaty of confederation signed with Tamasese, much to Germany's displeasure. However, after German threats, the Hawaiians sailed away. Gibson would be overthrown and jailed during the Hawaiian rebellion of 1887, removing the Hawaiians as a concern.[4] The Germans brought in the engineer and artillerist Eugen Brandeis to strengthen their fortifications in Mulinu'u and drill troops in early 1887. By August 1887, Samoa was virtually in the possession of Germany. Both Tamasese and Laupepa were largely powerless to stop this.[5]

Conflict

First phase: 1887–1889

On August 19, 1887, four German ships arrived at Apia Harbor, looking to expand Germany's new empire. Germany then issued an ultimatum to the nearly powerless Laupepa on August 23, accusing him of responsibility for trivial incidents such as the continuing occasional food theft from plantations (something nearly impossible to prevent, nor a major concern) and a supposed insult to the German Kaiser at a bar by a Samoan. Laupepa attempted to delay, but soon fled along with his advisors; 700 German soldiers landed and seized the government buildings. Tamasese was declared king by the Germans. The Germans threatened to exact "great sorrows" upon the country if Laupepa did not give himself up. Against the wishes of his followers, he did so, hoping to prevent a war. Laupepa was forced into exile in Germany. Tamasese took the title of Malietoa and became a puppet king at Mulinu'u, and Brandeis was appointed premier.[6]

The situation worsened in 1888. Disorder in Apia in August was quelled by Tamsese and Brandeis's troops. The island of Manono was bombarded by the German gunboat Adler, angering both Samoans and Americans who had property there. German fortifications were extended from Apia into Matautu. On September 9, Mata'afa Iosefo crowned himself king, the only remaining power source not controlled by the Germans. His forces moved on Tamasese's and drove them back, penning them into the Mulinu'u peninsula to a position near Laulii. The Germans sent a threatening letter to Mata'afa, which he promptly forwarded to the Americans and British. This triggered the Samoan crisis, a naval standoff between the German, American, and British ships. After years of inaction, the Americans now appeared ready to support the Samoans directly, and informed the Germans that if they aided Tamasese by bombarding Mata'afa's troops, they would open fire on the German ships. The Germans backed down, neutralizing the advantage of the navies.[7]

Eager to break the stalemate, the Germans embarked upon a plan to land at a plantation on Vailele on December 18. They hoped for support from Tamasese's forces, but none came. The troops attempted the landing regardless, and Mata'afa's warriors, armed with British guns, defeated the badly outnumbered Germans. They possibly could have wiped them out entirely, but perhaps fearing repercussions if they struck too great an insult to Germany, withdrew and allowed the Germans to retreat back to their ship as well. 16 men died and 40 were wounded. In 1889, German fortunes continued to decline; commander Brandeis left the island, Tamasese lost support; and the Germans unwisely arrested an English citizen after a declaration of martial law. Chancellor Bismarck, upon learning of this, replied with emphatic orders not to cause an international incident with Germany's trading partner in the British Empire over what he considered an unimportant sideshow in German affairs. The Americans, hearing of the unrest and eager to support their own commercial interests, sent further ships into Apia harbor.[8]

Interlude

The struggle came to a halt with the 1889 Apia cyclone. Many German and American ships were damaged and others sunk entirely; 145 men on warships were lost, and 5 merchant sailors died. The three Western powers met and finally agreed to a deal on June 14, 1889, "The Final Act of The Berlin Conference on Samoan Affairs" or "The Berlin General Act" for short. It was agreed that Malietoa Laupepa would be returned from exile and restored as King of Samoa, and Samoan independence would be guaranteed. It also created a Supreme Court that could adjudicate disputes between Western Powers and the Samoans, and also regulate land sales to Westerners. The government stipulated by this act would last ten years. Laupepa returned to Apia on August 11, 1889, and affairs were quiet at first, with all sides agreeing to go about in peace from August 1889–1891.[9]

Tamasese Titimaea died in April 1891. In May 31, 1891, Mata'afa left Apia for Maile. While he soon returned to Apia, he advocated for his right to stand in an election for leadership as provided by the terms of the Berlin General Act, perhaps believing his popularity from his victories in the struggle against German influence would hold up. The Western consuls were unanimous in standing by Laupepa, however. In early 1892, the government apparently attacked villages known for supporting Mata'afa, forcing their inhabitants into exile in Maile, damaging their buildings, and killing their livestock. The Mata'afa supporting parts of Samoa stopped paying taxes, causing fiscal problems for the government. The Chief Justice of the Supreme Court established by the Berlin General Act was expected to resolve the disputes, but he was apparently unable, and left Samoa for Europe in 1893.[10]

Second phase: 1893–1894

On April 26, 1893, Mata'afa claimed the kingship of Samoa for himself from his stronghold of Maile. On July 8, a government force of around 1,000 warriors attacked a smaller group of Mata'afa supporters at Vailele, and crushingly defeated them. The rout was sufficiently severe that Mata'afa, his supporting chieftains, and a small remnant of his forces fled Maile for Manono Island. He considered moving to Savaiʻi, but was warned that they would attack if he did, so he stayed on Manono. Fearful of bloodshed if Laupepa's forces attacked the islands, the British and Germans intervened; a British ship and a German ship headed to Manono and accepted an honorable surrender from Mata'afa without a fight. Mata'afa and a few of his supporters were exiled, eventually coming to Jaluit Atoll, which was then controlled by the German Empire.[11]

A new challenger to Laupepa arose in March 1894, with Tamasese Lealofi rebelling from Aʻana, the traditional seat of Tamasese power. Laupepa's government easily defeated Tamasese and a peace deal was made. Unrest seemed to have continued, however, and British and German warships bombarded some villages claimed to be in rebellion in August.[11]

Involved ships

American warships during the Samoan crisis included the USS Vandalia, Trenton (captained by Lewis Kimberly), and Nipsic. The British Empire sent a ship to protect its interests, HMS Calliope. The Germans had Olga, Adler, and Eber.[9]

Legacy

On August 22, 1898, Malietoa Laupepa died. Mata'afa returned from exile in September to contest the throne. The Supreme Court decided in December 1898 that the succession should go to Laupepa's son Malietoa Tanumafili I rather than Mata'afa, however. Hostilities soon resumed in the Second Samoan Civil War, with the returned Mata'afa quickly and easily defeating Tanumafili at the Siege of Apia. The Western powers eventually intervened. The result was the partitioning of the island chain at the Tripartite Convention of 1899 into the western German Samoa and the eastern American Samoa. The office of King of Samoa was abolished, and Samoan autonomy officially ended.[12]

The famous author Robert Louis Stevenson lived the final years of his life on Samoa, from 1889–1894. He would go on to document the struggle directly in the book A Footnote to History: Eight Years of Trouble in Samoa. The book includes his own experiences and a history of the turbulent decade based on direct interviews with Laupepa and others, and is considered one of the key primary sources chronicling the events.[11]

See also

References

- Morlang (2008), p. 128.

- Kennedy, p. 2–5

- Watson 1918, p. 64–66

- McBride, Spencer. "Mormon Beginnings in Samoa: Kimo Belio, Samuela Manoa and Walter Murray Gibson". Brigham Young University. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- Watson 1918, p. 67–74

- Watson 1918, p. 75–78

- Watson 1918, p. 78–81

- Watson 1918, p. 81–84

- Watson 1918, p. 85–98

- Watson 1918, p. 98–102

- Watson 1918, p. 102–105

- Watson 1918, p. 106–119

Bibliography

- Kennedy, Paul M. (1974). The Samoan Tangle: A Study in Anglo-German-American Relations 1878–1900. Dublin: Irish University Press. ISBN 0-7165-2150-4.

- Stevenson, Robert Louis (1912) [1892]. A Footnote to History: Eight Years of Trouble in Samoa. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-1857-9. OCLC 227258432.

- Morlang, Thomas (2008). Askari und Fitafita. "Farbige" Söldner in den deutschen Kolonien (in German). Berlin: Ch. Links Verlag.

- Watson, Robert Mackenzie (1918). History of Samoa. Wellington, Auckland, Christchurch, and Dunedin New Zealand: Whitcomb and Tombs Limited.