Fieldnotes

Fieldnotes refer to qualitative notes recorded by scientists or researchers in the course of field research, during or after their observation of a specific organism or phenomenon they are studying. The notes are intended to be read as evidence that gives meaning and aids in the understanding of the phenomenon. Fieldnotes allow researchers to access the subject and record what they observe in an unobtrusive manner.

_BHL46748940.jpg.webp)

One major disadvantage of taking fieldnotes is that they are recorded by an observer and are thus subject to (a) memory and (b) possibly, the conscious or unconscious bias of the observer.[1] It is best to record fieldnotes while making observations in the field or immediately after leaving the site to avoid forgetting important details. Some suggest immediately transcribing one's notes from a smaller pocket-sized notebook to something more legible in the evening or as soon as possible. Errors that occur from transcription often outweigh the errors which stem from illegible writing in the actual "field" notebook.[2]

Fieldnotes are particularly valued in descriptive sciences such as ethnography, biology, ecology, geology, and archaeology, each of which has long traditions in this area.

Structure

The structure of fieldnotes can vary depending on the field. Generally, there are two components of fieldnotes: descriptive information and reflective information.[3]

Descriptive information is factual data that is being recorded. Factual data includes time and date, the state of the physical setting, social environment, descriptions of the subjects being studied and their roles in the setting, and the impact that the observer may have had on the environment.[3]

Reflective information is the observer's reflections about the observation being conducted. These reflections are ideas, questions, concerns, and other related thoughts.[3]

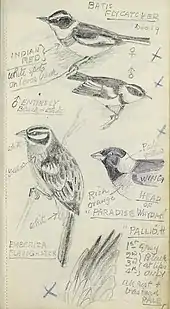

Fieldnotes can also include sketches, diagrams, and other drawings. Visually capturing a phenomenon requires the observer to pay more attention to every detail so as not to overlook anything.[4] An author does not necessarily need to possess great artistic abilities to craft an exceptional note. In many cases, a rudimentary drawing or sketch can greatly assist in later data collection and synthesis.[2] Increasingly, photographs may be included as part of a fieldnote when collected in a digital format.

Others may further subdivide the structure of fieldnotes. Nigel Rapport said that fieldnotes in anthropology transition rapidly among three types.[5]

- Inscription – where the writer records notes, impressions, and potentially important keywords.

- Transcription – where the author writes down dictated local text

- Description – a reflective type of writing that synthesizes previous observations and analysis for a later situation in which a more coherent conclusion can be made of the notes.[5]

Value

Fieldnotes are extremely valuable for scientists at each step of their training.[2] In an article on fieldnotes, James Van Remsen Jr. discussed the tragic loss of information from birdwatchers in his study area that could have been taking detailed fieldnotes but neglected to do so. This comment points to a larger issue regarding how often one should be taking fieldnotes. In this case, Remsen was upset because of the multitudes of "eyes and ears" that could have supplied potentially important information for his bird surveys but instead remained with the observers. Scientists like Remsen believe can be easily wasted if notes are not taken.

Currently, nature phone apps and digital citizen science databases (like eBird) are changing the form and frequency of field data collection and may contribute to de-emphasizing the importance of hand-written notes. Apps may open up new possibilities for citizen science, but taking time to handwrite fieldnotes can help with the synthesis of details that one may not remember as well from data entry in an app. Writing in such a detailed manner may contribute to the personal growth of a scientist.[2]

Nigel Rapport, an anthropological field writer, said that fieldnotes are filled with the conventional realities of "two forms of life": local and academic. The lives are different and often contradictory but are often brought together through the efforts of a "field writer".[5] The academic side refers to one's professional involvements, and fieldnotes take a certain official tone. The local side reflects more of the personal aspects of a writer and so the fieldnotes may also relate more to personal entries.

In biology and ecology

Taking fieldnotes in biology and other natural sciences will differ slightly from those taken in social sciences, as they may be limited to interactions regarding a focal species and/or subject. An example of an ornithological fieldnote was reported by Remsen (1977) regarding a sighting of a Cassin's sparrow, a relatively rare bird for the region where it was found.[2]

Grinnell method of note-taking

An important teacher of efficient and accurate note-taking is Joseph Grinnell. The Grinnell technique has been regarded by many ornithologists as one of the best standardized methods for taking accurate fieldnotes.[2]

The technique has four main parts:

- A field-worthy notebook where one records direct observations as they are being observed.

- A larger more substantial journal containing written entries on observations and information, transcribed from the smaller field notebook as soon as possible.

- Species accounts of the notes taken on specific species.

- A catalog to record the location and date of collected specimens.

In social sciences

Grounded theory

Methods for analyzing and integrating fieldnotes into qualitative or quantitative research are continuing to develop. Grounded theory is a method for integrating data in qualitative research done primarily by social scientists. This may have implications for fieldnotes in the natural sciences as well.[6]

Considerations when recording fieldnotes

Decisions about what is recorded and how can have a significant impact on the ultimate findings derived from the research. As such, creating and adhering to a systematic method for recording fieldnotes is an important consideration for a qualitative researcher. American social scientist Robert K. Yin recommended the following considerations as best practices when recording qualitative field notes.[7]

- Create vivid images: Focus on recording vivid descriptions of actions that take place in the field, instead of recording an interpretation of them. This is particularly important early in the research process. Immediately trying to interpret events can lead to premature conclusions that can prevent later insight when more observation has occurred. Focusing on the actions taking place in the field, instead of trying to describe people or scenes, can be a useful tool to minimize personal stereotyping of the situation.

- The verbatim principle: Similar to the vivid images, the goal is to accurately record what is happening in the field, not a personal paraphrasing (and possible unconscious stereotyping) of those events. Additionally, in social science research that involves studying culture, it is important to faithfully capture language and habits as a first step toward full understanding.

- Include drawings and sketches: These can quickly and accurately capture important aspects of field activity that are difficult to record in words and can be very helpful for recall when reviewing fieldnotes.

- Develop one's own transcribing language: While no one technique of transcribing (or "jotting") is perfect, most qualitative researchers develop a systematic approach to their own note-taking. Considering the multiple competing demands on attention (the simultaneous observation, processing, and recording of rich qualitative data in an unfamiliar environment), perfecting a system that can be automatically used and that will be interpretable later allows one to allocate one's full attention to observation. The ability to distinguish notes about events themselves from other notes to oneself is a key feature. Prior to engaging in qualitative research for the first time, practicing a transcribing format beforehand can improve the likelihood of successful observation.

- Convert fieldnotes to full notes daily: Prior to discussing one's observations with anyone else, one should set aside time each day to convert fieldnotes. At the very least, any unclear abbreviations, illegible words, or unfinished thoughts should be completed that would be uninterpretable later. In addition, the opportunity to collect one's thoughts and reflect on that day's events can lead to recalling additional details, uncovering emerging themes, leading to new understanding, and helping plan for future observations. This is also a good time to add the day's notes to one's total collection in an organized manner.

- Verify notes during collection: Converting fieldnotes as described above will likely lead the researcher to discover key points and themes that can then be checked while still present in the field. If conflicting themes are emerging, further data collection can be directed in a manner to help resolve the discrepancy.

- Obtain permission to record: While electronic devices and audiovisual recording can be useful tools in performing field research, there are some common pitfalls to avoid. Ensure that permission is obtained for the use of these devices beforehand and ensure that the devices to be used for recording have been previously tested and can be used inconspicuously.

- Keep a personal journal in addition to fieldnotes: As the researcher is the main instrument, insight into one's own reactions to and initial interpretations of events can help the researcher identify any undesired personal biases that might have influenced the research. This is useful for reflexivity.

References

- Asplund, M.; Welle, C. G. (2018). "Advancing Science: How Bias Holds Us Back". Neuron. 99 (4): 635–639. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2018.07.045. PMID 30138587. S2CID 52073870.

- Remsen, J.V. (1977). "On Taking Field Notes" (PDF). American Birds. 31:5: 946–953.

- Labaree, Robert V. "Research Guides: Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper: Writing Field Notes". libguides.usc.edu. Retrieved 2016-04-12.

- Canfield, Michael R., ed. (2011). Field Notes on Science & Nature. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. p. 162. doi:10.4159/harvard.9780674060845. ISBN 9780674057579. JSTOR j.ctt2jbxgp. OCLC 676725399.

- Rapport, Nigel (1991). "Writing Fieldnotes: The Conventionalities of Note-Taking and Taking Note in the Field". Anthropology Today. 7 (1): 10–13. doi:10.2307/3032670. JSTOR 3032670.

- Charmaz & Belgrave, K & L.L. (2015). "Grounded Theory". The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Sociology. doi:10.1002/9781405165518.wbeosg070.pub2. ISBN 9781405124331.

- Yin, Robert (2011). Qualitative Research from Start to Finish (Second ed.). New York, NY: The Guilford Press. pp. 163–183. ISBN 978-1-4625-1797-8.

Further reading

- Canfield, Michael R., ed. (2011). Field Notes on Science & Nature. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. doi:10.4159/harvard.9780674060845. ISBN 9780674057579. JSTOR j.ctt2jbxgp. OCLC 676725399.

- Emerson, Robert M.; Fretz, Rachel I.; Shaw, Linda L. (2011) [1995]. Writing Ethnographic Fieldnotes. Chicago Guides to Writing, Editing, and Publishing (2nd ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226206837. OCLC 715287276.

- Herman, Steven G. (1986) [1980]. The Naturalist's Field Journal: A Manual of Instruction Based on a System Established by Joseph Grinnell. Vermillion, SD: Buteo Books. ISBN 0931130131. OCLC 14712430.

- Sanjek, Roger, ed. (1990). Fieldnotes: The Makings of Anthropology. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. doi:10.7591/9781501711954. ISBN 0801424364. JSTOR 10.7591/j.ctvv4124m. OCLC 20722414.

- Sanjek, Roger; Tratner, Susan W., eds. (2016). eFieldnotes: The Makings of Anthropology in the Digital World. Haney Foundation series. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. doi:10.9783/9780812292213. ISBN 9780812247787. OCLC 908448234.

- Small, Mario Luis; Calarco, Jessica McCrory (2022). Qualitative Literacy: A Guide to Evaluating Ethnographic and Interview Research. Oakland, CA: University of California Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctv2vr9c4x. ISBN 9780520390652. JSTOR j.ctv2vr9c4x. OCLC 1302335774. S2CID 252033642.

- Vivanco, Luis Antonio (2017). Field Notes: A Guided Journal for Doing Anthropology. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190642198. OCLC 953918904.