Feminism: The Essential Historical Writings

Feminism: The Essential Historical Writings is an anthology edited with an introduction and commentaries by Miriam Schneir.[1] It was originally published in 1972 and re-published in 1994 by Vintage Books.[1] It comprises essays, fiction, memoirs, and letters by what Schneir labels the major feminist writers.[1] The content included ranges from 1776 to 1929 and focuses on topics of civil rights and emancipation.[1][2] The book has had an influence on education, being used as a resource in women's studies classes.[3][4] Various scholars have given both positive and negative reviews of this book. It remains in print to this day.

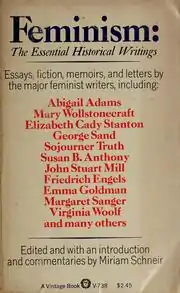

Cover of 1972 edition | |

| Editor | Miriam Schneir |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Published | 1972, 1994 |

| Publisher | Vintage Books |

| Pages | 374 |

Miriam Schneir

Personal life

Miriam Schneir was born in 1933 and grew up in New York City.[5] She comes from a middle-class family that was not politically engaged or involved in scholarship.[5] Her background is Jewish.[5] Her husband was Walter Schneir, who was born in 1927 and died in 2009.[6] Together they had two sons and one daughter.[6]

Education

Schneir graduated from Queens College in 1955, being the first person in her family to graduate from college.[5] Before graduating from Queens College, Schneir also attended Antioch College for two years.[5] At Antioch College, she majored in creative writing.[5] However, she earned her BA at Queens College where she studied early childhood education in order to get her teaching license.[5] The switch was prompted by the higher financial security of being a teacher.[5]

Career

Schneir initially worked as an early childhood educator after graduating from college.[5] In the 1960s, she became a full-time writer.[5] She served as research historian on the bicentennial museum exhibit and catalogue-book “Remember the Ladies”: Women in America, 1750-1815. She also held a position as a research associate with the Columbia University Center for Social Sciences Program in Sex Roles and Social Change.[5]

Views and politics

During her time at Antioch College, Schneir began to identify with leftist politics and ideas.[5] Her thinking has been influenced by her time at Antioch College and the communist colleagues she encountered in her career as an educator.[5] She opposes systems of inequality and has strived to take action against them.[5] She has also been active in rallies, petitions, and campaigning.[5] She was involved with the Adlai Stevenson and Henry A. Wallace campaigns.[5]

Work on Feminism: The Essential Historical Writings

In the late 1960s, Schneir was exposed to the concept of feminism for the first time.[5] Shortly after, because of her interest in the topic, she began to collect works and search for publishers for an anthology, which would later become Feminism: The Essential Historical Writings. Her feminist thought was influenced by Eleanor Flexner, Gerda Lerner, Aileen S. Kraditor, Simone de Beauvoir, Betty Friedan, and the works she was reading for the anthology.[5] She worked on the book vigorously, and it was published in January of 1972.[5]

Other works

- Co-author of Invitation to Inquest (1965)

- Editor of Feminism in Our Time: The Essential Writings, World War II to the Present (1994)

- Editor of The Vintage Book of Historical Feminism (1996)

- Writer of preface and afterword for Final Verdict: What Really Happened in the Rosenberg Case (2010)

- Writer of Before Feminism (2021)

Her work has also appeared in various publications such as Ms., The Nation, The New York Times Magazine, and many others.[7]

Introduction and commentaries

Schneir wrote the introduction and commentaries for this book.[1] In the book's introduction, she discusses the purpose of the book as uncovering feminist writings of the past, how the content included focuses on "unsolved feminist problems," and the past and future of the feminist movement.[1] For each work included in the book, she wrote a brief introduction to the work and its author.[1]

Content

The book is made up of essays, fiction, memoirs, and letters by what Schneir labels the major feminist writers, including Elizabeth Cady Stanton, George Sand, Mary Wollstonecraft, Abigail Adams, Emma Goldman, Friedrich Engels, Sojourner Truth, Susan B. Anthony, John Stuart Mill, Margaret Sanger, Virginia Woolf, and many others.[1] The materials in this book range from the 18th to 20th century, with the earliest work being from 1776 and the latest being from 1929.[1] Schneir describes this as the phase of "old feminism".[1] Most of the works included were written by Americans, with the addition of some by European writers.[1] The book has five sections: Eighteenth Century Rebels, Women Alone, An American Women’s Movement, Men as Feminists, and Twentieth-Century Themes.[1] The content is related to a theme of civil rights and emancipation, specifically focusing on topics of marriage, economic dependence, and personal independence and selfhood.[1][2][8] It also includes multiple works written by male socialists, linking ideas of feminism and socialism together.[3]

Choice of content

Schneir described her process of choosing the material for the book as looking for the basic, essential writings of feminism that everyone should know.[5] She justifies the use of predominantly American content through her American nationality and the idea that the United States was the world center of "old feminism".[1] The influence of Schneir’s leftist background can also be considered when examining the content chosen for this book.[3]

List of content included

Schneir includes experts from the works below. The works are listed in chronological order.

| Work | Author |

| Familiar Letters of John Adams and His Wife, Abigail Adams, During the Revolution | Abigail Adams |

| A Vindication of the Rights of Woman | Mary Wollstonecraft |

| Course of Popular Lectures | Frances Wright |

| Indiana | George Sand |

| Letters of George Sand | George Sand |

| The Intimate Journal of George Sand | George Sand |

| Letters on the Equality of the Sexes and the Condition of Women | Sarah Moore Grimké |

| Early Factory Labour in New England | Harriet M. Robinson |

| The Song of the Shirt | Thomas Hood |

| Woman in the Nineteenth Century | Margaret Fuller |

| Married Women's Property Act, New York, 1848 | N/A |

| Declaration of Sentiments and Resolutions, Seneca Falls | N/A |

| Editorial from The North Star | Frederick Douglass |

| Intelligent Wickedness | William Lloyd Garrison |

| Letter from Prison of St. Lazare, Paris | N/A |

| Ain't I a Woman? | Sojourner Truth |

| What Time of Night It Is | Sojourner Truth |

| Not Christianity, but Priestcraft | Lucretia Mott |

| Marriage of Lucy Stone Under Protest | Lucy Stone |

| Disappointment Is the Lot of Women | Lucy Stone |

| Address to the New York State Legislature, 1854 | Elizabeth Cady Stanton |

| Address to the New York State Legislature, 1860 | Elizabeth Cady Stanton |

| Married Women's Property Act, New York, 1860 | N/A |

| Petitions Were Circulated | Ernestine Rose |

| Keeping the Thing Going While Things are Stirring | Sojourner Truth |

| The United States of America vs. Susan B. Anthony | Susan B. Anthony |

| Woman Wants Bread, Not the Ballot! | Susan B. Anthony |

| Virtue: What It Is, and What It Is Not | Victoria Woodhull & Tennessee Claflin |

| Which Is to Blame? | Victoria Woodhull & Tennessee Claflin |

| The Elixir of Life | Victoria Woodhull & Tennessee Claflin |

| Womanliness | Elizabeth Cady Stanton |

| Solitude of Self | Elizabeth Cady Stanton |

| The Subjection of Women | John Stuart Mill |

| A Doll's House | Henrik Ibsen |

| The Origin of the Family, Private Property, and the State | Friedrich Engels |

| Women and Socialism | August Bebel |

| The Theory of the Leisure Class | Thorstein Veblen |

| Women and Economics | Charlotte Perkins Gilman |

| The Lady | Emily James Smith Putnam |

| Senate Report - History of Women in Industry in the United States | N/A |

| Women's Share in Social Culture | Anna Garlin Spencer |

| The World Movement for Woman Suffrage 1904 to 1911: Is Woman Suffrage Progressing? | Carrie Chapman Catt |

| I Incite This Meeting to Rebellion When Civil War Is Waged by Women | Emmeline Pankhurst |

| Bread and Roses | N/A |

| The Traffic in Women | Emma Goldman |

| Marriage and Love | Emma Goldman |

| Women and the New Race | Margaret Sanger |

| My Recollections of Lenin: An Interview on the Woman Question | Clara Zetkin |

| A Room of One's Own | Virginia Woolf |

| On Understanding Women | Mary Ritter Beard |

Influence

Educational use

This book has held influence in education as it has been used to teach students about feminism.[3][9] In the absence of the history of feminism from traditional history books, students studied this book in women's studies classes.[2][4] Some scholars say that it is an accessible and useful resource for undergraduate courses focusing on the history of feminism.[8] It is said to be good because it covers old materials in an engaging way and encourages students to continue learning about them.[2][8] Others recognize that it provides insight into how particular discourses and narratives are established and think of it as a resource for students to be critical of and challenge the dominant constructions of feminist history.[3]

Reviews

One common point of discussion throughout reviews is the construction of the history of feminism that this book produces. Knowledge production is often critiqued, as sometimes it is based on very few ideas. This book produces a knowledge of feminism without considering multiple ideas.[3] Some argue that this book highlights a linear progression of a western narrative of feminism, not examining feminism in different historical periods or different countries.[10] This results in the absence of diverse views and perspectives.[10] Further, some note that the book fails to consider race. The construction of feminist history produced in it both misrepresents and does not appropriately include Black women's perspectives.[11]

Multiple scholars mentioned Schneir's introduction and commentaries in their reviews. The writing on the back cover of the book is critiqued for being misleading. It states that the book highlights ignored or forgotten materials, but most of the material is actually pretty well known.[8] Some also feel that more critical introductions to the works and more critical bibliographies for each writer would have added value to the book.[10]

Some scholars recognize the importance of the book. They feel that it is an excellent collection of works from the history of feminism.[2] Others additionally note that the book holds historical significance.[3]

References

- Schneir, Miriam (1972). Feminism: The Essential Historical Writings. Vintage Books.

- Ripmaster, Terence (1974). "Review of Feminism: The Essential Historical Writings". The History Teacher. 8 (1): 125–126. doi:10.2307/491466. ISSN 0018-2745. JSTOR 491466.

- Moses, Claire Goldberg (2012). ""What's in a Name?" On Writing the History of Feminism". Feminist Studies. 38 (3): 757–779. ISSN 0046-3663. JSTOR 23720210.

- "Men and Women in Society". Feminist Teacher. 1 (2): 30–31. 1985. ISSN 0882-4843. JSTOR 25680532.

- Weigand, Katie (2004). "Interview with Miriam Schneir". Sophia Smith Collection: 1–70.

- Martin, Douglas (2009-04-25). "Walter Schneir, Who Wrote About Rosenbergs, Dies at 81 (Published 2009)". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2020-11-28.

- "Miriam Schneir | Penguin Random House". PenguinRandomhouse.com. Retrieved 2020-11-24.

- Ehrlich, Carol (1973). "The Woman Book Industry". American Journal of Sociology. 78 (4): 1030–1044. doi:10.1086/225419. ISSN 0002-9602. JSTOR 2776620. S2CID 144554579.

- Brandzel, Amy L. (2011). "Haunted by Citizenship: Whitenormative Citizen—Subjects and the Uses of History in Women's Studies". Feminist Studies. 37 (3): 503–533. ISSN 0046-3663. JSTOR 23069920.

- Mulvey, Helen F. (1973). "Review of Suffer and Be Still: Women in the Victorian Age, ; Feminism: The Essential Historical Writings". The Historian. 35 (3): 488–489. ISSN 0018-2370. JSTOR 24443054.

- Giardina, Carol (2018). "MOW to NOW: Black Feminism Resets the Chronology of the Founding of Modern Feminism". Feminist Studies. 44 (3): 736–765. doi:10.15767/feministstudies.44.3.0736. ISSN 0046-3663. JSTOR 10.15767/feministstudies.44.3.0736. S2CID 149782710.