Public Works Administration

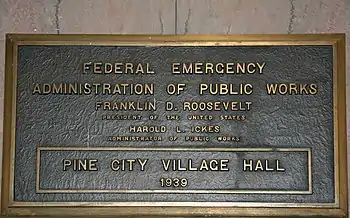

The Public Works Administration (PWA), part of the New Deal of 1933, was a large-scale public works construction agency in the United States headed by Secretary of the Interior Harold L. Ickes. It was created by the National Industrial Recovery Act in June 1933 in response to the Great Depression. It built large-scale public works such as dams, bridges, hospitals, and schools. Its goals were to spend $3.3 billion (about $10 per person in the U.S.) in the first year, and $6 billion (about $18 per person in the U.S.) in all, to supply employment, stabilize buying power, and help revive the economy. Most of the spending came in two waves, one in 1933–1935 and another in 1938. Originally called the Federal Emergency Administration of Public Works, it was renamed the Public Works Administration in 1935 and shut down in 1944.[1]

The PWA spent over $7 billion (about $22 per person in the U.S.) on contracts with private construction firms that did the actual work. It created an infrastructure that generated national and local pride in the 1930s and is still vital nine decades later. The PWA was much less controversial than its rival agency, the Works Progress Administration (WPA), headed by Harry Hopkins, which focused on smaller projects and hired unemployed unskilled workers.[2]

Origins

The Administration created the PWA in an attempt to help the U.S.'s economy recover after the Great Depression. Its major objective was to reduce unemployment, which was up to 24% of the work force. Furthermore the PWA also aimed at increasing purchase power by constructing new public buildings and roads. Frances Perkins had first suggested a federally financed public works program, and the idea received considerable support from Harold L. Ickes, James Farley, and Henry Wallace. After having scaled back the initial cost of the PWA, Franklin Delano Roosevelt agreed to include the PWA as part of his New Deal proposals in the "Hundred Days" of spring 1933.

Projects

The PWA headquarters in Washington planned projects, which were built by private construction companies hiring workers on the open market. Unlike the WPA, it did not hire the unemployed directly. More than any other New Deal program, the PWA epitomized the progressive notion of "priming the pump" to encourage economic recovery. Between July 1933 and March 1939, the PWA funded and administered the construction of more than 34,000 projects including airports, large electricity-generating dams, major warships for the Navy, and bridges and 70 percent of the new schools and a third of the hospitals built in 1933–1939.

Streets and highways were the most common PWA projects, as 11,428 road projects, or 33 percent of all PWA projects, accounting for over 15 percent of its total budget. School buildings, 7,488 in all, came in second at 14 percent of spending. PWA functioned chiefly by making allotments to the various federal agencies; making loans and grants to state and other public bodies; and making loans without grants (for a brief time) to the railroads. For example, it provided funds for the Indian Division of the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) to build roads, bridges, and other public works on and near Indian reservations.

_Spillway_01.jpg.webp)

The PWA became, with its "multiplier-effect" and a first two-year budget of $3.3 billion (compared to the entire GDP of $60 billion), the driving force of America's biggest construction effort up to that date. By June 1934, the agency had distributed its entire fund to 13,266 federal projects and 2,407 non-federal projects. For every worker on a PWA project, almost two additional workers were employed indirectly. The PWA accomplished the electrification of rural America, the building of canals, tunnels, bridges, highways, streets, sewage systems, and housing areas, as well as hospitals, schools, and universities; every year, it consumed roughly half of the concrete and a third of the steel of the entire nation.[3] The PWA also electrified the Pennsylvania Railroad between New York City and Washington, DC.[4] At the local level, it built courthouses, schools, hospitals, and other public facilities that remain in use in the 21st century.[5]

List of most notable PWA projects

- Bankhead Tunnel in Mobile, Alabama

- Lincoln Tunnel in New York City

Water/wastewater

- Detroit Sewage Disposal Project

Bridges

- Bourne Bridge

- Cape Cod Canal Railroad Bridge

- Overseas Highway connecting Key West, Florida, to the mainland

- Sagamore Bridge

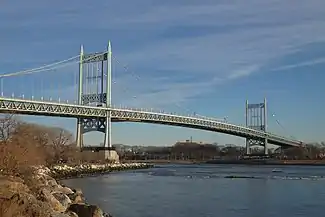

- Triborough Bridge

Dams

Airports

- Austin–Bergstrom International Airport[11]

- Charlotte Douglas International Airport[11]

- Hartsfield–Jackson Atlanta International Airport[11]

- Logan International Airport[11]

- Los Angeles International Airport[11]

- Nashville International Airport[11]

- Philadelphia International Airport[11]

- Portland International Airport[11]

- Salt Lake City International Airport[11]

- Tampa International Airport[11]

Housing

The PWA was supposed to be the centerpiece of the New Deal's drive to build public housing for the urban poor. Public housing was a new concept in the United States, tested for the first time during the New Deal. With this in mind the PWA constructed a total of 52 housing communities for a total of 29,000 units, which was less than what many supporters of public housing had hoped for. The very first public housing community built by PWA was the whites-only Techwood Homes in Atlanta, Georgia.[12] The PWA also built one of the first public housing projects in New York City, the Williamsburg Houses in Brooklyn.

Criticism

The PWA spent over $6 billion but did not succeed in returning the level of industrial activity to pre-Depression levels.[13][14] Though successful in many aspects, it has been acknowledged that the PWA's objective of constructing a substantial number of quality, affordable housing units was a major failure.[13][14] Some have argued that because Roosevelt was opposed to deficit spending, there was not enough money spent to help the PWA achieve its housing goals.[13][14]

Reeves (1973) argues that Roosevelt's competitive theory of administration proved to be inefficient and produced delays. The competition over the size of expenditure, the selection of the administrator, and the appointment of staff at the state level, led to delays and the ultimate failure of PWA as a recovery instrument. As director of the budget, Lewis Douglas overrode the views of leading senators in reducing appropriations to $3.5 billion and in transferring much of that money to other agencies instead of their own specific appropriations. The cautious and penurious Ickes won out over the more imaginative Hugh S. Johnson as chief of public works administration. Political competition between rival Democratic state organizations and between Democrats and Progressive Republicans led to delays in implementing PWA efforts on the local level. Ickes instituted quotas for hiring skilled and unskilled black people in construction financed through the PWA. Resistance from employers and unions was partially overcome by negotiations and implied sanctions. Although results were ambiguous, the plan helped provide African Americans with employment, especially among unskilled workers.[15]

Termination

%252C_in_1956.jpg.webp)

When Roosevelt moved industry toward World War II production, the PWA was abolished and its functions were transferred to the Federal Works Agency in June 1943.[16][17] The PWA played an indirect hand in the war by helping fund the construction of two aircraft carriers, Yorktown and Enterprise. Both of these ships played a significant role in the victory in Midway when they sank four Japanese aircraft carriers.[18] The PWA also built four cruisers, four heavy destroyers, light destroyers, submarines, planes, engines, and even instruments for these vessels.[18] The PWA helped get the US get ready to fight in World War II, giving the US an advantage with fresh boats, planes, and equipment.

Legacy

The PWA was responsible for the construction of about 34,000 buildings, bridges, and homes many of which are still in use today.[19] Among these is one of the most recognizable bridges in the U.S., the Triborough Bridge, which was renamed the Robert F. Kennedy Bridge.[20] PWA funded workers to construct the San Francisco Mint, which cost $1,072,254 to build,[21] as well as the Keys Overseas Highway in Florida. Although this highway was already built prior to the PWA's existence, PWA funding made the road usable again. The 1935 Labor Day hurricane had heavily damaged the highway, and the Florida East Coast Railway was only able to repair the bridge after the PWA came in and offered assistance.[22] A large majority of PWA projects are still in use today because of one big reason: the PWA allowed the state and local governments to pick what they wanted to have built or repaired, where they wanted the project as well as who they wanted to build it. Such freedom gave local governments the ability to select a truly useful building that could be used for years down the line.[23]

Contrast with WPA

The PWA should not be confused with its great rival, the Works Progress Administration (WPA), though both were part of the New Deal. The WPA, headed by Harry Hopkins, engaged in smaller projects in close cooperation with local governments—such as building a city hall or sewers or sidewalks. The PWA projects were much larger in scope, such as giant dams. The WPA hired only people on relief who were paid directly by the federal government. The PWA gave contracts to private firms that did all the hiring on the private sector job market. The WPA also had youth programs (the National Youth Administration), projects for women, and art projects that the PWA did not have.[24]

Citations

- "Records of the Public Works Administration". National Archives. August 15, 2016.

- Smith, Jason Scott (2006). Building New Deal Liberalism: The Political Economy of Public Works, 1933–1956. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521139939.

- George McJimsey, The Presidency of Franklin Delano Roosevelt (2000) "PWA (1939)", p 221;

- "P.R.R. WILL SPEND $77,000,000 AT ONCE; Atterbury Outlines Projects Under PWA Loan Giving Year's Work to 25,000. TO EXTEND ELECTRIC LINE Sees Buying Power Restored and Industry Stimulated by Wide Building Program", The New York Times, January 31, 1934, retrieved August 8, 2012

- Lowry, Charles B. (April 1974). "The PWA in Tampa: A Case Study". The Florida Historical Quarterly. Florida Historical Society. 52 (4): 363–380. JSTOR 30145930.

- ""New Deal Work Programs in Central Texas"". March 26, 2015. Retrieved December 13, 2018.

- "Pensacola Dam - Grand Lake OK - Living New Deal". March 26, 2015. Archived from the original on March 26, 2015. Retrieved September 26, 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - "Tom Miller Dam - Austin TX - Living New Deal". March 26, 2015. Archived from the original on March 26, 2015. Retrieved September 26, 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - "Upper Mississippi River Dam - Winona MN - Living New Deal". March 26, 2015. Archived from the original on March 26, 2015. Retrieved September 26, 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - "Rivers of Life: History of Transportation, part 3". Cgee.hamline.edu. Retrieved December 9, 2016.

- "New Deal Category: Airports". Living New Deal. Retrieved May 3, 2022.

- Perry-Brown, Nena (May 29, 2020). "A brew of advocacy and agency concocted the US public housing system that we know today". ggwash.org. Retrieved April 27, 2022.

- Roosevelt, Franklin Delano (1985). Graham, Otis L.; Wander, Meghan Robinson (eds.). Franklin D. Roosevelt: His Life and Times : an Encyclopedic View. G.K. Hall. pp. 336–337. ISBN 9780816186679.

- Leuchtenburg, William E. (1963). Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal: 1932-1940. Harper Perennial. pp. 133–134. ISBN 9780061836961.

- Kruman, Marc W. (1975). "Quotas for blacks: The public works administration and the black construction worker". Labor History. 16 (1): 37–51. doi:10.1080/00236567508584321.

- Roosevelt, Franklin D. (June 30, 1943). Woolley, John T.; Peters, Gerhard (eds.). "Executive Order 9357 - Transferring the Functions of the Public Works Administration to the Federal Works Agency". The American Presidency Project. University of California.

- Olson, James Stuart (2001). Historical Dictionary of the Great Depression, 1929-1940. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 9780313306181.

- Thompson, Lisa (November 18, 2016). "Public Works Administration (PWA), 1933-1943". The Living New Deal. Retrieved May 11, 2022.

- "Public Works Administration (PWA), 1933-1943". Living New Deal. Retrieved April 27, 2022.

- "Public Works Administration (PWA), 1933-1943". Living New Deal. Retrieved April 26, 2022.

- "United States Mint - San Francisco CA". Living New Deal. Retrieved April 26, 2022.

- "Overseas Highway - Florida Keys FL". Living New Deal. November 2, 2014. Retrieved April 27, 2022.

- "Public Works Administration (PWA), 1933-1943". Living New Deal. Retrieved April 27, 2022.

- Taylor, Nick (2009). American-made: The Enduring Legacy of the WPA : when FDR Put the Nation to Work. Bantam Books. ISBN 9780553381320.

General and cited sources

- Clarke, Jeanne Nienaber (1996). Roosevelt's Warrior: Harold L. Ickes and the New Deal. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 9780801850943.

- Ickes, Harold L. (2018). Back to Work: The Story of Pwa. Creative Media Partners, LLC. ISBN 9780344562273.

- Ickes, Harold L. (May 1935). "The Place of Housing in National Rehabilitation". The Journal of Land & Public Utility. University of Wisconsin Press. 11 (2): 109–116. doi:10.2307/3158654. JSTOR 3158654.

- Reeves, William D. (September 1973). "PWA and Competition Administration in the New Deal". The Journal of American History. Oxford University Press. 60 (2): 357–372. doi:10.2307/2936780. JSTOR 2936780.

- America Builds: The Record of P.W.A. Public Works Administration. 1939. ISBN 9781978016040.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)