Father of surgery

Various individuals have advanced the surgical art and, as a result, have been called the Father of Surgery by various sources.

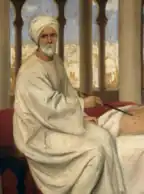

Abu al-Qasim al-Zahrawi

The Arab physician Abu al-Qasim al-Zahrawi (936-1013) wrote Al-Tasrif (The Method of Medicine), a 30-part medical encyclopedia in Arabic. In the encyclopedia, he introduced his collection of over 200 surgical instruments, many of which were never used before.[1] Some of his works included being the first to describe and prove the hereditary pattern behind hemophilia, as well as describing ectopic pregnancy and stone babies.[2] He has been called the "father of surgery".[3][4]

The 14th century French surgeon Guy de Chauliac quoted Al-Tasrif over 200 times. Abu Al-Qasim's influence continued for at least five centuries after his death, extending into the Renaissance, evidenced by al-Tasrif's frequent reference by French surgeon Jacques Daléchamps (1513-1588).[4]

Guy de Chauliac

The Frenchman Guy de Chauliac (c. 1300–1368) is said by the Encyclopædia Britannica to have been the most eminent surgeon of the European Middle Ages. He wrote the surgical work Chirurgia magna, which was used as a standard text for some centuries.[5] He has been called the "father of modern surgery".[6]

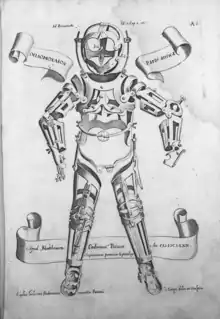

Ambroise Paré

The French surgeon Ambroise Paré (1517–1590) worked as a military doctor. He reformed the treatment of gunshot wounds, rejecting the practice, common at that time, of cauterizing the wound, and ligatured blood vessels in amputated limbs. His collected works were published in 1575. He has been called the "father of modern surgery".[7][8][9]

Hieronymus Fabricius

The Italian anatomist and surgeon Hieronymus Fabricius (1537–1619) taught William Harvey, and published a work on the valves of the veins. He has been called the "father of ancient surgery".[10][11]

John Hunter

The Scotsman John Hunter (1728–1793) was known for his scientific, experimental approach to medicine and surgery.[12] He has been called the "father of modern surgery".[13][14]

Philip Syng Physick

The American surgeon Philip Syng Physick (1768–1837) worked in Philadelphia and invented a number of new surgical methods and instruments.[15] He has been called the "father of modern surgery".[16][17]

Joseph Lister

The Englishman Joseph Lister (1827–1912) became well known for his advocacy of the use of carbolic acid (phenol) as an antiseptic, and was dubbed the "father of modern surgery" as a result.[18][19]

Theodor Billroth

The German Theodor Billroth (1829–1894) was an early user of antisepsis, and was the first to perform a resection of the esophagus, and various other operations. He has been called the "father of modern surgery".[20][21]

William Stewart Halsted

The American William Stewart Halsted (1852–1922) pioneered the radical mastectomy, and designed a residency training program for American surgeons.[22][23] He has been called "the most innovative and influential surgeon the United States has produced", and also the "father of modern surgery".[24][25]

James Henderson Nicoll

The Scottish James Henderson Nicoll (1863–1921) pioneered a surgical cure for Pyloric stenosis and outpatient care of children with Spina bifida,[26] and was known as the Father of Day Surgery.[27]

Gallery

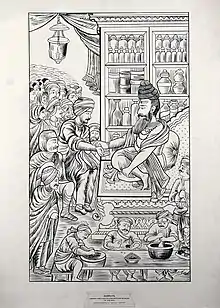

Susruta

Susruta Al-Zahrawi

Al-Zahrawi Guy de Chauliac

Guy de Chauliac Ambroise Paré

Ambroise Paré Hieronymus Fabricius

Hieronymus Fabricius John Hunter

John Hunter Philip Syng Physick

Philip Syng Physick Joseph Lister

Joseph Lister Theodor Billroth

Theodor Billroth William Stewart Halsted

William Stewart Halsted

References

- Holmes-Walker, Anthony (2004). Life-enhancing plastics : plastics and other materials in medical applications. London: Imperial College Press. p. 176. ISBN 978-1-86094-462-8.

- Martín-Araguz, A; Bustamante-Martínez, C; Fernández-Armayor Ajo, V; Moreno-Martínez, JM (2002). "[Neuroscience in Al Andalus and its influence on medieval scholastic medicine]". Revista de Neurología. 34 (9): 877–92. doi:10.33588/rn.3409.2001382. PMID 12134355.

- Ahmad, Z. (St Thomas' Hospital) (2007), "Al-Zahrawi - The Father of Surgery", ANZ Journal of Surgery, 77 (Suppl. 1): A83, doi:10.1111/j.1445-2197.2007.04130_8.x, S2CID 57308997

- Badeau, John Stothoff; Hayes, John Richard (1983). Hayes, John Richard (ed.). The Genius of Arab civilization: source of Renaissance (2nd ed.). MIT Press. p. 200. ISBN 978-0262580632.

- "Guy de Chauliac", in Encyclopædia Britannica Online, Encyclopædia Britannica, 2011. Accessed on line April 18, 2011.

- p. 283, Old-Time Makers of Medicine, James J. Walsh, New York: Fordham University Press, 1911.

- p. 9, Trauma: Emergency resuscitation, perioperative anesthesia, surgical management, vol. 1, ed. by William C. Wilson, Christopher M. Grande, and David B. Hoyt, CRC Press, 2007, ISBN 0-8247-2919-6.

- pp. 41-48, The History of Medicine: The Scientific Revolution and Medicine: 1450-1700, Kate Kelly, Facts on File, Inc., 2009, ISBN 0-8160-7207-8.

- "Ambroise Paré", Leopold Senfelder, in The Catholic Encyclopedia, vol. 11, New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1911.

- p. 289, New general biographical dictionary, vol. 7, Hugh James Rose, ed., London: B. Fellowes et al., 1848.

- p. 1080, Edinburgh Medical Journal 34, #11 (May 1889), Edinburgh: Oliver and Boyd, Tweeddale Court, and London: Simpkin, Marshall, and Co.

- pp. 13-17, John Hunter: Man of science and surgeon (1728-1793), Stephen Paget, introd. by James Paget, London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1897.

- Gray, C (May 1983). "The remarkable surgical collection of John Hunter". Can Med Assoc J. 128 (10): 1225–8. PMC 1875296. PMID 6340814.

- The knife man: the extraordinary life and times of John Hunter, father of modern surgery, Wendy Moore, Random House, 2005, ISBN 0-7679-1652-2.

- Edwards, G (January 1940). "Philip Syng Physick, 1768–1837: (Section of the History of Medicine)". Proc. R. Soc. Med. 33 (3): 145–8. PMC 1997417. PMID 19992186.

- Luck, Raemma P.; et al. (2008). "Cosmetic Outcomes of Absorbable Versus Nonabsorbable Sutures in Pediatric Facial Lacerations". Pediatric Emergency Care. 24 (3): 137–142 [140]. doi:10.1097/PEC.0b013e3181666f87. PMID 18347489. S2CID 9639004.

- Rivera, AM; Strauss, KW; van Zundert, A; Mortier, E (2005). "The history of peripheral intravenous catheters: how little plastic tubes revolutionized medicine" (PDF). Acta Anaesthesiol Belg. 56 (3): 271–82 [273]. PMID 16265830.

- pp. 51-55, Pioneers of microbiology and the Nobel prize, Ulf Lagerkvist, World Scientific, 2003, ISBN 981-238-234-8.

- Joseph Lister, Father of Modern Surgery, Rhoda Truax, Bobbs Merrill, Indianapolis and New York, 1944.

- p. 35, The history of cancer: an annotated bibliography, James Stuart Olson, ABC-CLIO, 1989, ISBN 0-313-25889-9.

- p. 253, Vascular Graft Update: Safety and Performance, ASTM Committee F-4 on Medical and Surgical Materials and Devices, ASTM International, 1986, ISBN 0-8031-0462-6.

- p. 124, The cancer treatment revolution: how smart drugs and other new therapies are renewing our hope and changing the face of medicine, David G. Nathan, John Wiley and Sons, 2007, ISBN 0-471-94654-0.

- pp. 132-134, Seeking the Cure: A History of Medicine in America, Ira M. Rutkow, Simon and Schuster, 2010, ISBN 1-4165-3828-3.

- Cameron, JL (May 1997). "William Stewart Halsted. Our surgical heritage". Ann. Surg. 225 (5): 445–58. doi:10.1097/00000658-199705000-00002. PMC 1190776. PMID 9193173.

- Voorhees, J. R.; Tubbs, R. S.; Nahed, B.; Cohen-Gadol, A. A. (February 2009). "William S. Halsted and Harvey W. Cushing: reflections on their complex association". Journal of Neurosurgery. 110 (2): 384–390. doi:10.3171/2008.4.17516. PMID 18976064.

- Willetts, IE (July 1997). "James H Nicoll: pioneer paediatric surgeon". Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. 79 (4 (Supp)): 164–167. PMID 9496166.

- John G. Raffensperger, M.D. (8 March 2012). Children's Surgery: A Worldwide History. McFarland. p. 114. ISBN 978-0-7864-9048-6. Retrieved 11 July 2018.