Exterior derivative

On a differentiable manifold, the exterior derivative extends the concept of the differential of a function to differential forms of higher degree. The exterior derivative was first described in its current form by Élie Cartan in 1899. The resulting calculus, known as exterior calculus, allows for a natural, metric-independent generalization of Stokes' theorem, Gauss's theorem, and Green's theorem from vector calculus.

| Part of a series of articles about |

| Calculus |

|---|

If a differential k-form is thought of as measuring the flux through an infinitesimal k-parallelotope at each point of the manifold, then its exterior derivative can be thought of as measuring the net flux through the boundary of a (k + 1)-parallelotope at each point.

Definition

The exterior derivative of a differential form of degree k (also differential k-form, or just k-form for brevity here) is a differential form of degree k + 1.

If f is a smooth function (a 0-form), then the exterior derivative of f is the differential of f . That is, df is the unique 1-form such that for every smooth vector field X, df (X) = dX f , where dX f is the directional derivative of f in the direction of X.

The exterior product of differential forms (denoted with the same symbol ∧) is defined as their pointwise exterior product.

There are a variety of equivalent definitions of the exterior derivative of a general k-form.

In terms of axioms

The exterior derivative is defined to be the unique ℝ-linear mapping from k-forms to (k + 1)-forms that has the following properties:

- df is the differential of f for a 0-form f .

- d(df ) = 0 for a 0-form f .

- d(α ∧ β) = dα ∧ β + (−1)p (α ∧ dβ) where α is a p-form. That is to say, d is an antiderivation of degree 1 on the exterior algebra of differential forms (see the graded product rule).

The second defining property holds in more generality: d(dα) = 0 for any k-form α; more succinctly, d2 = 0. The third defining property implies as a special case that if f is a function and α is a k-form, then d( fα) = d( f ∧ α) = df ∧ α + f ∧ dα because a function is a 0-form, and scalar multiplication and the exterior product are equivalent when one of the arguments is a scalar.

In terms of local coordinates

Alternatively, one can work entirely in a local coordinate system (x1, ..., xn). The coordinate differentials dx1, ..., dxn form a basis of the space of one-forms, each associated with a coordinate. Given a multi-index I = (i1, ..., ik) with 1 ≤ ip ≤ n for 1 ≤ p ≤ k (and denoting dxi1 ∧ ... ∧ dxik with dxI), the exterior derivative of a (simple) k-form

over ℝn is defined as

(using the Einstein summation convention). The definition of the exterior derivative is extended linearly to a general k-form

where each of the components of the multi-index I run over all the values in {1, ..., n}. Note that whenever i equals one of the components of the multi-index I then dxi ∧ dxI = 0 (see Exterior product).

The definition of the exterior derivative in local coordinates follows from the preceding definition in terms of axioms. Indeed, with the k-form φ as defined above,

Here, we have interpreted g as a 0-form, and then applied the properties of the exterior derivative.

This result extends directly to the general k-form ω as

In particular, for a 1-form ω, the components of dω in local coordinates are

Caution: There are two conventions regarding the meaning of . Most current authors have the convention that

while in older text like Kobayashi and Nomizu or Helgason

In terms of invariant formula

Alternatively, an explicit formula can be given [1] for the exterior derivative of a k-form ω, when paired with k + 1 arbitrary smooth vector fields V0, V1, ..., Vk:

where [Vi, Vj] denotes the Lie bracket and a hat denotes the omission of that element:

In particular, when ω is a 1-form we have that dω(X, Y) = dX(ω(Y)) − dY(ω(X)) − ω([X, Y]).

Note: With the conventions of e.g., Kobayashi–Nomizu and Helgason the formula differs by a factor of 1/k + 1:

Examples

Example 1. Consider σ = u dx1 ∧ dx2 over a 1-form basis dx1, ..., dxn for a scalar field u. The exterior derivative is:

The last formula, where summation starts at i = 3, follows easily from the properties of the exterior product. Namely, dxi ∧ dxi = 0.

Example 2. Let σ = u dx + v dy be a 1-form defined over ℝ2. By applying the above formula to each term (consider x1 = x and x2 = y) we have the following sum,

Stokes' theorem on manifolds

If M is a compact smooth orientable n-dimensional manifold with boundary, and ω is an (n − 1)-form on M, then the generalized form of Stokes' theorem states that:

Intuitively, if one thinks of M as being divided into infinitesimal regions, and one adds the flux through the boundaries of all the regions, the interior boundaries all cancel out, leaving the total flux through the boundary of M.

Further properties

Closed and exact forms

A k-form ω is called closed if dω = 0; closed forms are the kernel of d. ω is called exact if ω = dα for some (k − 1)-form α; exact forms are the image of d. Because d2 = 0, every exact form is closed. The Poincaré lemma states that in a contractible region, the converse is true.

de Rham cohomology

Because the exterior derivative d has the property that d2 = 0, it can be used as the differential (coboundary) to define de Rham cohomology on a manifold. The k-th de Rham cohomology (group) is the vector space of closed k-forms modulo the exact k-forms; as noted in the previous section, the Poincaré lemma states that these vector spaces are trivial for a contractible region, for k > 0. For smooth manifolds, integration of forms gives a natural homomorphism from the de Rham cohomology to the singular cohomology over ℝ. The theorem of de Rham shows that this map is actually an isomorphism, a far-reaching generalization of the Poincaré lemma. As suggested by the generalized Stokes' theorem, the exterior derivative is the "dual" of the boundary map on singular simplices.

Naturality

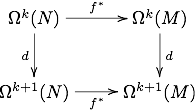

The exterior derivative is natural in the technical sense: if f : M → N is a smooth map and Ωk is the contravariant smooth functor that assigns to each manifold the space of k-forms on the manifold, then the following diagram commutes

so d( f∗ω) = f∗dω, where f∗ denotes the pullback of f . This follows from that f∗ω(·), by definition, is ω( f∗(·)), f∗ being the pushforward of f . Thus d is a natural transformation from Ωk to Ωk+1.

Exterior derivative in vector calculus

Most vector calculus operators are special cases of, or have close relationships to, the notion of exterior differentiation.

Gradient

A smooth function f : M → ℝ on a real differentiable manifold M is a 0-form. The exterior derivative of this 0-form is the 1-form df.

When an inner product ⟨·,·⟩ is defined, the gradient ∇f of a function f is defined as the unique vector in V such that its inner product with any element of V is the directional derivative of f along the vector, that is such that

That is,

where ♯ denotes the musical isomorphism ♯ : V∗ → V mentioned earlier that is induced by the inner product.

The 1-form df is a section of the cotangent bundle, that gives a local linear approximation to f in the cotangent space at each point.

Divergence

A vector field V = (v1, v2, ..., vn) on ℝn has a corresponding (n − 1)-form

where denotes the omission of that element.

(For instance, when n = 3, i.e. in three-dimensional space, the 2-form ωV is locally the scalar triple product with V.) The integral of ωV over a hypersurface is the flux of V over that hypersurface.

The exterior derivative of this (n − 1)-form is the n-form

Curl

A vector field V on ℝn also has a corresponding 1-form

Locally, ηV is the dot product with V. The integral of ηV along a path is the work done against −V along that path.

When n = 3, in three-dimensional space, the exterior derivative of the 1-form ηV is the 2-form

Invariant formulations of operators in vector calculus

The standard vector calculus operators can be generalized for any pseudo-Riemannian manifold, and written in coordinate-free notation as follows:

where ⋆ is the Hodge star operator, ♭ and ♯ are the musical isomorphisms, f is a scalar field and F is a vector field.

Note that the expression for curl requires ♯ to act on ⋆d(F♭), which is a form of degree n − 2. A natural generalization of ♯ to k-forms of arbitrary degree allows this expression to make sense for any n.

See also

Notes

- Spivak(1970), p 7-18, Th. 13

References

- Cartan, Élie (1899). "Sur certaines expressions différentielles et le problème de Pfaff". Annales Scientifiques de l'École Normale Supérieure. Série 3 (in French). Paris: Gauthier-Villars. 16: 239–332. doi:10.24033/asens.467. ISSN 0012-9593. JFM 30.0313.04. Retrieved 2 Feb 2016.

- Conlon, Lawrence (2001). Differentiable manifolds. Basel, Switzerland: Birkhäuser. p. 239. ISBN 0-8176-4134-3.

- Darling, R. W. R. (1994). Differential forms and connections. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 35. ISBN 0-521-46800-0.

- Flanders, Harley (1989). Differential forms with applications to the physical sciences. New York: Dover Publications. p. 20. ISBN 0-486-66169-5.

- Loomis, Lynn H.; Sternberg, Shlomo (1989). Advanced Calculus. Boston: Jones and Bartlett. pp. 304–473 (ch. 7–11). ISBN 0-486-66169-5.

- Ramanan, S. (2005). Global calculus. Providence, Rhode Island: American Mathematical Society. p. 54. ISBN 0-8218-3702-8.

- Spivak, Michael (1971). Calculus on Manifolds. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press. ISBN 9780805390216.

- Spivak, MIchael (1970), A Comprehensive Introduction to Differential Geometry, vol. 1, Boston, MA: Publish or Perish, Inc, ISBN 0-914098-00-4

- Warner, Frank W. (1983), Foundations of differentiable manifolds and Lie groups, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, vol. 94, Springer, ISBN 0-387-90894-3

External links

- Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: "The derivative isn't what you think it is". Aleph Zero. November 3, 2020 – via YouTube.