Siege of Boston

The siege of Boston (April 19, 1775 – March 17, 1776) was the opening phase of the American Revolutionary War.[5] In the siege, American patriot militia led by newly-installed Continental Army commander George Washington prevented the British Army, which was garrisoned in Boston, from moving by land. Both sides faced resource, supply, and personnel challenges during the siege. British resupply and reinforcement was limited to sea access, which was impeded by American vessels. The British ultimately abandoned Boston after eleven months, moving their troops and equipment north, to Nova Scotia.

| Siege of Boston | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of American Revolutionary War | |||||||

Illustration depicting the British evacuation of Boston | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 7,000–16,000[1] | 5,000–11,000[2] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

Battle of Bunker Hill Over 400 killed or wounded, 30 captured[3] Rest of siege 19 killed or wounded[4] |

Bunker Hill About 1,000 killed or wounded[3] Rest of siege 60 killed or wounded, 35 captured[4] | ||||||

The siege began on April 19 after the Revolutionary War's first battles at Lexington and Concord, when Massachusetts militias blocked land access to Boston. The Continental Congress, meeting in Philadelphia, formed the Continental Army from the militias involved in the fighting and appointed George Washington as commander in chief. In June 1775, the British seized Bunker Hill and Breed's Hill, which Washington and the Continental Army was preparing to bombard, but their casualties were heavy and their gains insufficient to break the Continental Army's control over land to Boston. After this, the Americans laid siege to Boston; no major battles were fought during this time, and the conflict was limited to occasional raids, minor skirmishes, and sniper fire. British efforts to supply their troops were significantly impeded by the smaller but more agile Continental Army and patriot forces that were operating on land and sea. The British suffered from a continual lack of food, fuel, and supplies.

In November 1775, George Washington sent Henry Knox on a mission to bring the heavy artillery that had recently been captured at Fort Ticonderoga. In a technically complex and demanding operation, Knox brought the cannons to Boston in January 1776, and this artillery fortified Dorchester Heights which overlooked Boston harbor. This development threatened to cut off the British supply lifeline from the sea. British commander William Howe saw his position as indefensible, and he withdrew his forces from Boston to Halifax, Nova Scotia on March 17.

Background

.svg.png.webp)

Before 1775, the British imposed taxes and import duties on the American colonies, to which the Americans objected since they lacked British Parliamentary representation. In response to the Boston Tea Party and other acts of protest, 4,000 British troops were sent to occupy Boston under the command of General Thomas Gage and to pacify the restive Province of Massachusetts Bay.[7] Parliament authorized Gage to disband the government of Massachusetts Bay, led by John Hancock and Samuel Adams, among numerous other powers, but the Americans formed the Massachusetts Provincial Congress and continued to meet. The Provincial Congress called for the organization of local militias and coordinated the accumulation of weapons and other military supplies.[8] Under the terms of the Boston Port Act, Gage closed the Boston port, which caused much unemployment and discontent.[9]

British forces went to seize military supplies from the town of Concord on April 19, 1775, but militia companies from surrounding towns opposed them at the Battles of Lexington and Concord.[10] At Concord, some of the British forces were routed in a confrontation at the North Bridge. The British troops were then engaged in a running battle during their march back to Boston, suffering heavy casualties.[11] All of the New England colonies raised militias in response to this alarm and sent them to Boston.[12]

Order of battle

British Army

The British army order of battle in July 1775 was:[13]

- Commander-in-Chief of the British Army in America, Major General Sir William Howe, 5th Viscount Howe

- Commander of Artillery & Engineers, Colonel Cleveland (commanding officer of the 4th Battalion)

- No.1 Company, 4th Battalion, Royal Artillery

- No.2 Company, 4th Battalion, Royal Artillery

- No.4 Company, 4th Battalion, Royal Artillery

- No.5 Company, 4th Battalion, Royal Artillery

- No.8 Company, 4th Battalion, Royal Artillery

- x2 Companies of Invalids

- 1st Division, commanded by Major General Sir Henry Clinton

- 17th Regiment of (Light) Dragoons (4 Squadrons)

- 1st Brigade, commanded by Brigadier General His Grace Hugh Percy, 2nd Duke of Northumberland

- 3rd Brigade, commanded by Brigadier General Paget

- 5th Brigade, commanded by Brigadier General James Grant, Laird of Ballindalloch

- 2nd Division, commanded by Major General John Burgoyne

- 2nd Brigade, commanded by Brigadier General Jones

- 4th Brigade, commanded by Brigadier General James Robertson

- 18th Regiment of Foot/65th Regiment of Foot (combined)

- 40th Regiment of Foot

- 49th Regiment of Foot

- 2nd Battalion, Royal Marines

Royal Navy

- British North American Squadron (only those ships based in/around Boston listed)[14]

- HMS Boyne (70 guns)

- HMS Somerset (68 guns)

- HMS Asia (64 guns)

- HMS Preston (50 guns)

- HMS Mercury (20 guns)

- HMS Glasgow (20 guns)

- HMS Diana (6 guns)

- In Marblehead, Massachusetts:

- HMS Lively (20 guns)

United Colonies Army

- Army of Massachusetts (Continental Army), commanded by Commander-in-Chief General George Washington[15]

- Commander of Artillery Brigadier General Henry Knox

- Continental Artillery Regiment

- Rhode Island Artillery Company

- Massachusetts Line

- Frye's Massachusetts Regiment

- Pennsylvania Rifle Regiment

- Learned's Massachusetts Regiment

- Nixon's Massachusetts Regiment

- J. Brewer's Massachusetts Regiment

- Fellow's Massachusetts Regiment

- D. Brewer's Massachusetts Regiment

- Prescott's Massachusetts Regiment

- Cotton's Massachusetts Regiment

- Little's Massachusetts Regiment

- Danielson's Massachusetts Regiment

- Mansfield's Massachusetts Regiment

- Read's Massachusetts Regiment

- Glover's Massachusetts Regiment

- Walker's Massachusetts Regiment

- Whitcomb's Massachusetts Regiment

- Woodbridge's Massachusetts Regiment

- Bridge's Massachusetts Regiment

- Sargent's Massachusetts Regiment

- Scammon's Massachusetts Regiment

- Phinney's Massachusetts Regiment

- Ward's Massachusetts Regiment

- Thomas's Massachusetts Regiment

- Heath's Massachusetts Regiment

- Gardner's Massachusetts Regiment

- Gerrish's Massachusetts Regiment

- New Hampshire Line

- Rhode Island Line

- Connecticut Line

- Commander of Artillery Brigadier General Henry Knox

Siege

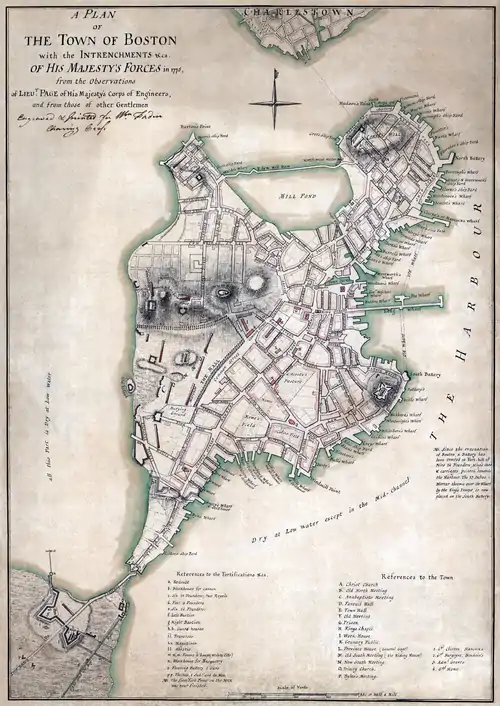

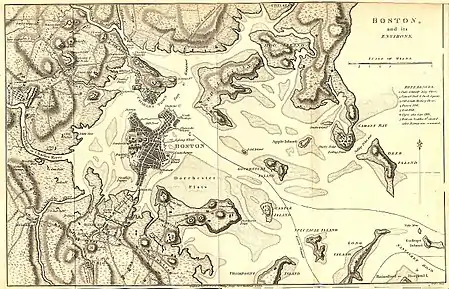

Immediately after the battles of April 19, the Massachusetts militia formed a siege line extending from Chelsea, around the peninsulas of Boston and Charlestown, to Roxbury, effectively surrounding Boston on three sides. The siege line was under the loose leadership of William Heath, who was superseded by General Artemas Ward late on the 20th.[16] They particularly blocked the Charlestown Neck, the only land access to Charlestown, and the Boston Neck, the only land access to Boston, which was then a peninsula, leaving the British in control only of the harbor and sea access.[12]

The size of the colonial forces grew in the following days, as militias arrived from New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Connecticut.[12] General Gage wrote of his surprise at the number of Patriots surrounding the city: "The rebels are not the despicable rabble too many have supposed them to be.... In all their wars against the French they never showed such conduct, attention, and perseverance as they do now."[17]

General Gage turned his attention to fortifying easily defensible positions. He ordered lines of defenses with ten 24-pound guns in Roxbury. In Boston proper, four hills were quickly fortified. They were to be the main defense of the city.[18] Over time, each of these hills was strengthened.[19] Gage also decided to abandon Charlestown, removing the beleaguered forces that had retreated from Concord. The town of Charlestown itself was entirely vacant, and Bunker Hill and Breed's Hill were left undefended, as were the heights of Dorchester, which had a commanding view of the harbor and the city.[20]

The British at first greatly restricted movement in and out of the city, fearing infiltration of weapons. Besieged and besiegers eventually reached an informal agreement allowing traffic on the Boston Neck, provided that no firearms were carried. Residents of Boston turned in almost 2,000 muskets, and most of the Patriot residents left the city.[21] Many Loyalists who lived outside the city of Boston left their homes and fled into the city. Most of them felt that it was not safe to live outside of the city, because the Patriots were now in control of the countryside.[22] Some of the men arriving in Boston joined Loyalist regiments attached to the British army.[23]

The siege did not blockade the harbor and the city remained open for the Royal Navy to bring in supplies from Nova Scotia and other places under Vice Admiral Samuel Graves. Colonial forces could do little to stop these shipments due to the superiority of the British fleet. Nevertheless, American privateers were able to harass supply ships, and food prices rose quickly. Soon the shortages meant that the British forces were on short rations. Generally, the American forces were able to gather information about what was happening in the city from people escaping the privations of Boston, but General Gage had no effective intelligence of American activities.[24]

Early skirmishes

On May 3, the Massachusetts Provincial Congress authorized Benedict Arnold to raise forces for taking Fort Ticonderoga near the southern end of Lake Champlain in the Province of New York, which was known to have heavy weapons and only lightly defended. Arnold arrived in Castleton, New Hampshire on the 9th, where he joined with Ethan Allen and a militia company from Connecticut, all of whom had independently arrived at the idea of taking Ticonderoga. This company captured Fort Ticonderoga and Fort Crown Point under the joint leadership of Arnold and Allen. They also captured the one large military vessel on Lake Champlain in a raid on Fort Saint-Jean.[25] They recovered more than 180 cannons and other weaponry and supplies that the Continental Army used to tighten their grip on Boston.[26]

Boston lacked a regular supply of fresh meat, and many horses needed hay. On May 21, Gage ordered a party to go to Grape Island in the outer harbor and bring hay to Boston.[27] The Continentals on the mainland noticed this and called out the militia. As the British party arrived, they came under fire from the militia. The militia set fire to a barn on the island, destroying 80 tons of hay and preventing the British from taking more than three tons.[27]

Continental forces worked to clear the harbor islands of livestock and supplies useful to the British. The Royal Marines attempted to stop removal of livestock from some of the islands on May 27 in the Battle of Chelsea Creek. The Americans resisted and the British schooner Diana ran aground and was destroyed.[28] Gage issued a proclamation on June 12 offering to pardon all of those who would lay down their arms, with the exception of John Hancock and Samuel Adams,[29][30] but this merely ignited anger among the Patriots, and more people began to take up arms.[29]

Breed's Hill

The British had been receiving reinforcements throughout May until they reached a strength of about 6,000 men. On May 25, Generals William Howe, John Burgoyne, and Henry Clinton arrived on HMS Cerberus, and Gage began planning to break out of the city.[28]

The British plan was to fortify Bunker Hill and Dorchester Heights. They fixed the date for taking Dorchester Heights at June 18, but the colonists' Committee of Safety learned of the British plans on June 15. In response, they sent instructions to General Ward to fortify Bunker Hill and the heights of Charlestown, and he ordered Colonel William Prescott to do so. On the night of June 16, Prescott led 1,200 men over the Charlestown Neck and constructed fortifications on Bunker Hill and Breed's Hill.[31]

British forces under General Howe took the Charlestown peninsula on June 17 in the Battle of Bunker Hill.[32] The British succeeded in their tactical objective of taking the high ground on the Charlestown peninsula, but they suffered significant losses with some 1,000 men killed or wounded, including 92 officers killed. The British losses were so heavy that there were no further direct attacks on American forces.[33] The Americans lost the battle but had again stood against the British regulars with some success, as they successfully repelled two assaults on Breed's Hill during the engagement.[34]

Stalemate

General George Washington arrived at Cambridge on July 2. He set up his headquarters at the Benjamin Wadsworth House at Harvard College[35] and took command of the newly formed Continental Army the following day. By this time, forces and supplies were arriving, including companies of riflemen from as far away as Maryland and Virginia.[36] Washington began the work of molding the militias into an army, appointing senior officers (the militias had typically elected their leaders), and introducing more organization and disciplinary measures.[37]

Washington required officers of different ranks to wear differentiating apparel so that they might be distinguished from their underlings and superiors.[38] On July 16, he moved his headquarters to the John Vassall House in Cambridge, that became well known as the home of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. Toward the end of July, about 2,000 riflemen arrived in units raised in Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia. The accuracy of the rifle was previously unknown in New England, and these forces were used to harass the besieged forces.[39]

Washington also ordered the defenses to be improved, so the army dug trenches on Boston Neck and then extended toward Boston. However, these activities had little effect on the British occupation.[40] The working parties were fired on from time to time, as were sentries guarding the works. The British pushed back an American advanced guard on July 30, and they burned a few houses in Roxbury.[41] An American rifleman was killed on August 2, and the British hung his body by the neck. In retaliation, American riflemen marched to the lines and began to attack the British troops. They continued their sharpshooting all day, killing and wounding many of the British while losing only one Patriot.[42]

On August 30, the British made a surprise breakout from Boston Neck, set fire to a tavern, and withdrew to their defenses.[42] On the same night, 300 Americans attacked Lighthouse Island and burned the lighthouse, killing several British soldiers and capturing 23, with the loss of only one American.[42] On another August night, Washington sent 1,200 men to dig entrenchments on a hill near the Charlestown Neck. Despite a British bombardment, the Americans successfully dug the trenches.[43]

In early September, Washington began drawing up plans for two moves: to dispatch 1,000 men from Boston to invade Quebec, and to launch an attack on Boston.[44] He felt that he could afford to send some troops to Quebec, as he had received intelligence from British deserters and American spies that the British had no intention of launching an attack from Boston until they were reinforced.[45] On September 11, about 1,100 troops under the command of Benedict Arnold left for Quebec.[46] Washington summoned a council of war and made a case for an amphibious assault on Boston by sending troops across Back Bay in flat-bottomed boats which could hold 50 men each.[47] He believed that it would be extremely difficult to keep the men together when winter came. His war council unanimously rejected the plan, and the decision was not to attack "for the present at least."[47]

In early September, Washington authorized the appropriation and outfitting of local fishing vessels for intelligence-gathering and interdiction of supplies to the British. This activity was a precursor to the Continental Navy, which was established in the aftermath of the British Burning of Falmouth in Portland, Maine. The provincial assemblies of Connecticut and Rhode Island began arming ships and authorized privateering.[48]

In early November, 400 British soldiers went to Lechmere's Point on a raiding expedition to acquire some livestock. They made off with 10 head of cattle but lost two lives in the skirmish with colonial troops sent to defend the point.[49][50] On November 29, colonial Captain John Manley commanding the schooner Lee captured one of the most valuable prizes of the siege: the British brigantine Nancy just outside Boston Harbor. She was carrying a large supply of ordnance and military stores intended for the British troops in Boston.[51]

As winter approached, the Americans were so short of gunpowder that some of the soldiers were given spears instead of guns.[52] Many of the American troops remained unpaid and many of their enlistments were set to expire at the end of the year.

Howe had replaced Gage in October as commander of the British forces, and was faced with different problems. Firewood was so scarce that British soldiers resorted to cutting down trees and tearing down wooden buildings, including the Old North Meeting House.[53] The city had become increasingly difficult because of winter storms and the rise in American privateers.[52] An improvised American war fleet of about 12 converted merchant ships captured 55 British ships over the course of the winter. Many of the captured ships had been carrying food and supplies to the British troops.[54] The British troops were so hungry that many were ready to desert as soon as they could, and scurvy and smallpox had broken out in the city.[55] Washington's army faced similar problems with smallpox, as soldiers from rural communities were exposed to the disease. He moved infected troops to a separate hospital, the only option available given the public stigma against inoculation.[56]

Washington again proposed to assault Boston in October, but his officers thought it best to wait until the harbor had frozen over.[57] In February, the water froze between Roxbury and Boston Common, and Washington thought that he would try an assault by rushing across the ice in spite of his shortage in powder; but his officers again advised against it. Washington's desire to launch an attack on Boston arose from his fear that his army would desert in the winter, and he knew that Howe could easily break the lines of his army in its present condition. He abandoned an attack across the ice with great reluctance in exchange for a more cautious plan of fortifying Dorchester Heights using cannon arrived from Fort Ticonderoga.[58][59]

British Major General Henry Clinton and a small fleet set sail for the Carolinas in mid-January with 1,500 men. Their objective was to join forces with additional troops arriving from Europe, and to take a port in the southern colonies for further military operations.[60] In early February, a British raiding party crossed the ice and burned several farmhouses in Dorchester.[61]

End of the siege

Between November 1775 and February 1776, Colonel Henry Knox and a team of engineers used sledges to retrieve 60 tons of heavy artillery that had been captured at Fort Ticonderoga, bringing them across the frozen Hudson and Connecticut rivers in a difficult, complex operation. They arrived back at Cambridge on January 24, 1776.[62]

Fortification of Dorchester Heights

Some of the Ticonderoga cannons were of a size and range not previously available to the Americans. They were placed in fortifications around the city, and the Americans began to bombard the city on the night of March 2, 1776, to which the British responded with cannonades of their own.[63] The American guns under the direction of Colonel Knox continued to exchange fire with the British until March 4. The exchange of fire did little damage to either side, although it did damage houses and kill some British soldiers in Boston.[64]

On March 5, Washington moved more of the Ticonderoga cannon and several thousand men overnight to occupy Dorchester Heights, overlooking Boston. The ground was frozen, which made it impossible to dig trenches, so Rufus Putnam developed a plan to fortify the heights using defenses made of heavy timbers and fascines.[65] These were prefabricated out of sight of the British and brought in overnight.[65][66][67][68] General Howe is said to have exclaimed, "My God, these fellows have done more work in one night than I could make my army do in three months."[69][65] The British fleet was within range of the American guns on Dorchester Heights, putting it and the troops in the city at risk.[70]

The immediate response of the British was a two-hour cannon barrage at the heights, which had no effect because the British guns could not reach the American guns.[71] After the failure of the barrage, Howe and his officers agreed that the colonists must be removed from the heights if they were to hold Boston. They planned an assault on the heights, but the attack never took place because of a storm, and the British elected instead to withdraw.[72]

On March 8, some prominent Bostonians sent a letter to Washington, stating that the British would not destroy the town if they were allowed to depart unmolested. Washington formally rejected the letter, as it was not addressed to him by either name or title.[73] However, the letter had the intended effect; when the evacuation began, there was no American fire to hinder the British departure. On March 9, the British saw movement on Nook's Hill in Dorchester and opened a massive artillery barrage that lasted all night. It killed four men with one cannonball, but that was all the damage that was done.[74] The next day, the colonists went out and collected the 700 cannonballs that had been fired at them.[74]

Evacuation

On March 10, 1776, General Howe issued a proclamation ordering the inhabitants of Boston to give up all linen and woolen goods that could be used by the colonists to continue the war. Loyalist Crean Brush was authorized to receive these goods, in return for which he gave certificates that were effectively worthless.[75] Over the next week, the British fleet sat in Boston harbor waiting for favorable winds, while Loyalists and British soldiers were loaded onto the ships. During this time, American naval vessels outside the harbor successfully captured several British supply ships.[76]

On March 15, the wind became favorable for the British, but it turned against them before they could leave. On March 17, the wind once again turned favorable. The troops were authorized to burn the town if there were any disturbances while they were marching to their ships;[75] they began to move out at 4:00 a.m. By 9:00 a.m., all ships were underway.[77] The fleet departing from Boston included 120 ships, with more than 11,000 people on board. Of those, 9,906 were British troops, 667 were women, and 553 were children.[78]

Aftermath

.jpg.webp)

Once the British fleet sailed away, the Americans moved to reclaim Boston and Charlestown. At first, they thought that the British were still on Bunker Hill, but it turned out that the British had left dummies in place.[78] Initially, Artemas Ward led a troop of men into Boston who had already been exposed to smallpox, out of fear that others might be exposed who had no resistance to the disease. More of the colonial army entered on March 20, 1776, once the risk of disease was judged to be low.[79] Washington had not hindered the British departure from the city by land, but he did not make their escape easy from the outer harbor. He directed Captain Manley to harass the departing British fleet, in which he had some success, capturing the ship carrying Crean Brush and his plunder, among other prizes.[80]

General Howe left in his wake a small contingent of vessels whose primary purpose was to intercept any arriving British vessels. They redirected numerous ships to Halifax that were carrying British troops originally destined for Boston. Some unsuspecting British troop ships landed in Boston, only to fall into American hands.[81]

The British departure ended major military activities in the New England colonies. Washington feared that the British were going to attack New York City and so departed on April 4 with his army for Manhattan, beginning the New York and New Jersey campaign.[82]

There are six units of the Army National Guard derived from American units that participated in the siege of Boston: 101st Eng Bn,[83] 125th MP Co,[84] 181st Inf,[85] 182nd Inf,[86] 197th FA,[87] and 201st FA.[88] There are 30 units in the U.S. Army with lineages that go back to the colonial era.

"Had Sir William Howe fortified the hills round Boston, he could not have been disgracefully driven from it," wrote his replacement Sir Henry Clinton.[89] General Howe was severely criticized in the British press and Parliament for his failures in the Boston campaign, but he remained in command for another two years for the New York and New Jersey campaign and the Philadelphia campaign. General Gage never received another combat command. General Burgoyne saw action in the Saratoga campaign, a disaster that resulted in the capture of Burgoyne and 7,500 troops under his command. General Clinton commanded the British forces in America for four years (1778–1782).[90]

Many Massachusetts Loyalists left with the British when they evacuated Boston. Some went to England to rebuild lives there, and some returned to America after the war. Many went to Saint John, New Brunswick.[91]

Following the siege, Boston ceased to be a military target but continued to be a focal point for revolutionary activities, with its port acting as an important point for fitting ships of war and privateers. Its leading citizens had important roles in the development of the United States.[92] Boston and other area communities mark March 17 as Evacuation Day.

See also

- American Revolutionary War §Early Engagements. The siege of Boston placed in sequence and strategic context.

- Battle of Gloucester, capture of British seamen attempting to enforce blockade in Gloucester Harbor

- Battle of Machias, Boston-based ship captured in Machias Bay

- Fort Washington, Massachusetts, surviving colonial position used during the siege

- List of conflicts in the United States#18th century

- List of Washington's Headquarters during the Revolutionary War

Footnotes

- McCullough, p. 25

- Frothingham, p. 311 puts the military strength that evacuated Boston at 11,000. Chidsey, p. 5 puts the initial strength at 4,000.

- See Battle of Bunker Hill infobox for casualty details.

- Boatner, p. 10

- "Siege of Boston – American Revolution – history.com". history.com. Archived from the original on December 22, 2016. Retrieved December 20, 2016.

- Ryan P. Randolph, Betsy Ross: The American Flag, and Life in a Young America, p. 38

- Chidsey, p. 5

- Frothingham, pp. 35, 54

- Frothingham, p. 7

- McCullough, p. 7

- See Battles of Lexington and Concord for the full story.

- Frothingham, pp. 100–101

- George Nafziger, British Forces under Howe 16 July 1775 Archived March 7, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, United States Army Combined Arms Center.

- George Nafziger, British North American Squadron 1 January 1775 Archived March 7, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, United States Army Combined Arms Center.

- George Nafziger, American Army of the United Colonies August 1775 Archived March 7, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, United States Army Combined Arms Center.

- McCullough, p. 35

- Harvey, p. 1

- French, p. 236

- French, p. 237

- French, pp. 126–128,220

- Chidsey, p. 53

- French, p. 228

- French, p. 234

- McCullough, p. 118

- Fisher, pp. 318–321

- Chidsey, p. 60

- French, p. 248

- French, p. 249

- French, p. 251

- Gage, Thomas; Flucker, Thomas, Secr'y (June 12, 1775). A proclamation whereas the infatuated multitudes, who have long suffered themselves to be conducted by certain well known incendiaries and traitors, in a fatal progression of crimes, against the constitutional authority of the state, have at length proceeded to avowed rebellion. Boston, Massachusetts: Printer not identified. p. 1. Archived from the original on June 30, 2022. Retrieved December 9, 2020.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - French, pp. 255–258

- French, p. 288

- French, p. 284

- French, pp. 272–273

- Benjamin Wadsworth House Archived April 16, 2014, at the Wayback Machine from Historic Buildings of Massachusetts.

- Chidsey, p. 117

- Chidsey, p. 113

- Chidsey, p. 112

- Frothingham, pp. 227–228

- McCullough, p. 10

- French, p. 337

- McCullough, p. 39

- French, p. 311

- McCullough, p. 50

- McCullough, p. 51

- Smith, pp. 57–58

- McCullough, p. 53

- French, pp. 319–320

- French, p. 338

- Frothingham, p. 267

- Chidsey, p. 133

- McCullough, p. 60

- p.78

- Atkinson, Rick (2019). "The Ways of Heaven are Dark and Intricate". The British Are Coming. New York: Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 978-1250231321.

- McCullough, p. 61

- Ann M. Becker, "Smallpox in Washington's Army: Strategic Implications of the Disease During the American Revolutionary War, The Journal of Military History, Vol. 68 No. 2 (April 2004) 388

- French, p. 330

- Fisher, p. 1

- Frothingham, pp. 295–296

- McCullough, p. 78

- McCullough, p. 86

- McCullough, p. 84

- McCullough, p. 91

- McCullough, p. 92

- Hubbard, Robert Ernest. General Rufus Putnam: George Washington's Chief Military Engineer and the "Father of Ohio," pp. 45-8, McFarland & Company, Inc., Jefferson, North Carolina. ISBN 978-1-4766-7862-7.

- Hubbard, Robert Ernest. Major General Israel Putnam: Hero of the American Revolution, pp. 158, McFarland & Company, Inc., Jefferson, North Carolina, 2017. ISBN 978-1-4766-6453-8.

- Philbrick, Nathaniel. Bunker Hill: A City, a Siege, a Revolution, pp. 274-7, Viking Penguin, New York, New York, 2013 (ISBN 978-0-670-02544-2).

- Livingston, William Farrand. Israel Putnam: Pioneer, Ranger and Major General, 1718-1790, pp. 269-70, G.P. Putnam's Sons, New York and London, 1901.

- McCullough, p. 93

- Frothingham, pp. 298–299

- McCullough, p. 94

- McCullough, p. 95

- Frothingham, pp. 303–304

- McCullough, p. 99

- McCullough, p. 104

- Frothingham, p. 308

- Frothingham, p. 309

- McCullough, p. 105

- Frothingham, pp. 310–311

- French, p. 429

- French, p. 436

- McCullough, p. 112

- Department of the Army, Lineage and Honors, 101st Engineer Battalion

- "Department of the Army, Lineage and Honors, 125th Quartermaster Company". Massachusetts National Guard. Archived from the original on December 18, 2014.

- Department of the Army, Lineage and Honors, 181st Infantry. Reproduced in Sawicki 1981, pp. 354–355.

- Department of the Army, Lineage and Honors, 182nd Infantry. Reproduced in Sawicki 1981, pp. 355–357.

- Department of the Army, Lineage and Honors, 172nd Field Artillery and 197th Field Artillery. See also "Unit Histories: From Portsmouth Harbor to the Persian Gulf," New Hampshire Army National Guard Pamphlet 600-82-3.

- Department of the Army, Lineage and Honors, 201st Field Artillery.

- Thomas Fleming, The Enigma of General Howe (2017) p. 1

- French, pp. 437–438

- French, pp. 438–439

- French, pp. 441–443

Bibliography

- Allison, Robert J. "George Washington and the Siege of Boston." in A Companion to George Washington (2012): 137-152.

- Barbier, Brooke. Boston in the American Revolution: A Town Versus an Empire (Arcadia Publishing, 2017).

- Boatner, Mark (1966). The Encyclopedia of the American Revolution. McKay. ISBN 0-8117-0578-1.

- Chidsey, Donald Barr (1966). The Siege of Boston. New York: Crown Publishers.

- Fisher, Sydney George (1908). The Struggle for American Independence. J.B. Lippincott Company.

- French, Allen (1911). The Siege of Boston. Macmillan.

- Frothingham Jr, Richard (1851). History of the Siege of Boston and of the Battles of Lexington, Concord, and Bunker Hill. Little and Brown. Archived from the original on September 28, 2023. Retrieved November 26, 2015.

- Harvey, Robert (2002). A Few Bloody Noses: The Realities and Mythologies of the American Revolution. Overlook Press. p. 160. ISBN 1-58567-273-4.

- Hazelgrove, William. Henry Knox's Noble Train: The Story of a Boston Bookseller's Heroic Expedition that Saved the American Revolution (Rowman & Littlefield, 2020).

- McCullough, David (2005). 1776. Simon and Schuster Paperback. ISBN 0-7432-2672-0.

- Philbrick, Nathaniel. Bunker Hill: A City, a Siege, a Revolution (Random House, 2013).

- Sawicki, James A. (1981). Infantry Regiments of the US Army. Dumfries, VA: Wyvern Publications. ISBN 978-0-9602404-3-2.

- Smith, Justin H (1903). Arnold's March from Cambridge to Quebec. New York: G. P. Putnams Sons.

Primary sources

- Timothy Newell (1852). "A journal kept during the time yt Boston was shut up in 1775-6". Collections of the Massachusetts Historical Society. 1.