Eurybrachidae

Eurybrachidae (sometimes misspelled "Eurybrachyidae" or "Eurybrachiidae") is a small family of planthoppers with species occurring in parts of Asia, Australia and Africa. They are remarkable for the sophistication of their automimicry.

| Eurybrachidae | |

|---|---|

| |

| Paropioxys jucundus | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hemiptera |

| Suborder: | Auchenorrhyncha |

| Infraorder: | Fulgoromorpha |

| Superfamily: | Fulgoroidea |

| Family: | Eurybrachidae Stål, 1862 |

| Subfamilies | |

Etymology

The family name is derived from the Greek ευρος (euros) and βραχυς (brachus), meaning "broad" and "short". This presumably reflects the shape of adults of representative species.

Description

Eurybrachidae generally resemble related families of planthoppers in the Fulgoromorpha. They are moderate-sized insects, generally 1 to 3 cm long when mature, but they are unobtrusive and camouflaged with brown, grey or green blotches, mimicking foliage, bark or lichens.[1] Their mottled camouflage patterns are most intense on the large forewings of many species, hiding the broad and often aposematically colourful abdomen. The frons of the head is characteristic, being broader than it is long.[2]

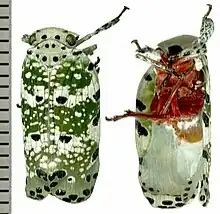

Paropioxys jucundus

Paropioxys jucundus

dorsal view Paropioxys jucundus

Paropioxys jucundus

ventral view Australian Eurybrachid, showing broad frons

Australian Eurybrachid, showing broad frons

Biology

Eurybrachidae generally are sap-suckers of trees or shrubs. In Australia, the genus Platybrachys associates with Eucalyptus trees, while the genera Olonia and Dardus associate with Acacia.

Each eurybrachid female is likely to have an adult lifespan of some months, during which she lays several clutches of eggs. Females of many species deposit the eggs in clusters on bark or the undersides of leaves, placed in a fingerprint sized patch of white waxy material, covered by a white capsule that protects them from many predators. However, small parasitoid wasps are adapted to attack the eggs by piercing the capsules with their ovipositors, and some species of beetles, such as some Coccinellidae will chew through the capsule and eat the eggs if they find a clutch.[3]

The nymphs, being less agile than the adults, rely on mimicry, camouflage for direct protection. However, they also secrete honeydew that attracts ants. The ants in turn protect them from wide varieties of predators and parasitoids.

The southeast Asian genus Ancyra is well known for the adult insects having a pair of prolonged filaments at the tips of the forewings; the wings are folded back when the insect is not in flight, so that the tips with their attached filaments are at the posterior end. The tips arise near a pair of small glossy spots; this creates the impression of a pair of antennae, with corresponding "eyes", a remarkable example of automimicry.[4] The "false head" effect is further reinforced by the bugs' habit of walking backwards when it detects movement nearby, so as to misdirect predators to strike at its rear, rather than at its actual head, and to strike in the anticipated direction of leaping, whereas the insect jumps in the opposite direction, away from the false head and initial direction of movement.

Other genera, including many African, Asian, and Australasian species, have closely analogous habits, but the automimicry occurs in the wingless nymphs instead of the winged adults. The pseudo-antennae of such nymphs are attached to the sub-posterior dorsal surface of the abdomen of the wingtips. The structure is visible in some of the illustrations in this article. The adults lack the pseudo-antennae, as may be seen for example for example in the illustration of Paropioxys jucundus. When the nymphs with the posterior pseudo-antennae are disturbed they wave them and walk backwards towards the threat in much the same way as the adults of Asiatic species that have filaments on their wingtips. Such nymphs similarly leap in misleading directions when sufficiently alarmed. However, not all species are equipped for that characteristic automimicry; in some genera, such as Eurybrachys, whether this genus is correctly taxonomically assigned or otherwise, the nymphs bear caudal tufts of bristles such as one typically finds in other families of the Fulgoroidea.[5]

Taxonomy

The oldest known Eurybrachid is from the middle Eocene of Messel.[6] The fossil genus Amalaberga is not placeable within the modern classification in two subfamilies Platybrachinae and Eurybrachinae.[7]

- Unplaced genera

- †Amalaberga Szwedo & Wappler, 2006

- Gastererion Perroud & Montrouzier, 1864

- Kamabrachys Constant, 2023

Platybrachinae

.jpg.webp)

- Tribe Ancyrini Schmidt, E., 1908 (monotypic)

- Ancyra White, A., 1845

- Tribe Dardini Schmidt, E., 1908

- Dardus Stål, 1859

- Gelastopsis Kirkaldy, 1906

- Metoponitys Karsch, 1890

- Ricanocephalus Melichar, 1898

- Tribe Platybrachini Schmidt, E., 1908

- Aspidonitys Karsch, 1895

- Euronotobrachys Kirkaldy, 1906

- Fletcherobrachys Constant, 2006

- Gedrosia Stål, 1862

- Hackerobrachys Constant, 2006

- Kirkaldybrachys Constant, 2006

- Loisobrachys Constant, 2008

- Maeniana Metcalf, 1952

- Mesonitys Schmidt, E., 1908

- Neoplatybrachys Lallemand, 1950

- Nirus Jacobi, 1928

- Olonia Stål, 1862

- Platybrachys Stål, 1859

- Stalobrachys Constant, 2018

- Usambrachys Constant, 2005

Eurybrachinae

%252C_Eurybrachidae._at_Mechod_Padur.jpg.webp)

Authority: Stål, 1862

- tribe Eurybrachini Stål, 1862 – India, Indochina, Malesia

- Eurybrachys Guérin-Méneville, 1834 - type genus

- Messena Stål, 1861

- Nicidus Stål, 1858

- Purusha Distant, 1906

- Thessitus Walker, 1862

- tribe Frutini Schmidt, 1908 – Malesia

- Chalia Walker, 1858

- tribe Loxocephalini Schmidt, 1908 – tropical Africa, India, China, Indochina

- Amychodes Karsch, 1895

- Klapperibrachys Constant, 2006

- Loxocephala Schaum, 1850

- Macrobrachys Lallemand, 1950

- Nesiana Metcalf, 1952

- Nilgiribrachys Constant, 2007

- Parancyra Synave, 1968

- Paropioxys Karsch, 1890

Pest status

Most Eurybrachidae are not regarded as pests, but like many families of plant sucking Hemiptera, they do include some species of concern. For example, Eurybrachys tomentosa is regarded as a pest of tropical Asian forestry, causing damage in plantations of sandalwood and Calotropis.[5]

See also

References

- Alan Weaving; Mike Picker; Griffiths, Charles Llewellyn (2003). Field Guide to Insects of South Africa. New Holland Publishers, Ltd. ISBN 1-86872-713-0.

- Scholtz, C.H.; Holm, E. (1985). Insects of Southern Africa. Butterworths. p. 158. ISBN 0-409-10487-6.

- Australian Eurybrachyid Planthoppers

- Wickler, W. (1968) Mimicry in plants and animals, McGraw-Hill, New York

- David, B. Vasantharaj; E. John Larsen (1978). General and Applied Entomology. Tata McGraw-Hill Education. p. 398. ISBN 978-0-07-043435-6.

- Szwedo, Jacek; Wappler, Torsten (2006) New planthoppers (Insecta: Hemiptera: Fulgoromorpha) from the Middle Eocene Messel maar. Annales Zoologici 56(3):555-566.

- FLOW database

External links

Data related to Eurybrachidae at Wikispecies

Data related to Eurybrachidae at Wikispecies Media related to Eurybrachidae at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Eurybrachidae at Wikimedia Commons- Australian species review

- Observations in the Brisbane area, Australia

- Photo of African species in defensive pose

.jpg.webp)