Environmental issues in the San Joaquin Valley

The San Joaquin Valley of California has seen environmental issues arise from agricultural production, industrial processing and the region's use as a transportation corridor.

Geographically, the San Joaquin Valley stretches from the Tehachapi Mountains in the south, between the California coastal ranges and the Sierra Nevada range, and opening into Sacramento–San Joaquin River Delta in the north. Much of the large, flat land area is devoted to large-scale agricultural production, although there are some significant urban centers such Fresno, Bakersfield, Clovis, Stockton, Modesto, and Visalia. It provides a transportation connection between populous northern California and southern California via I-5 and CA-99.

Water pollution

Surface water pollution

The San Joaquin River and its tributaries form the San Joaquin River watershed which spans the entire valley. The water quality in the San Joaquin River is degraded due to runoff from irrigated agriculture, other agricultural activities (such as dairies and feed lots), municipalities. Elevated levels of selenium, fluoride and nitrates have been measured in the river and its tributaries. The selenium is believed to originate from soils on the west side of the valley and in the Coast Ranges, which are rich with the element. Additionally, the San Joaquin is suffering chronic salinity problems due to high levels of minerals being washed off the land by irrigation practices. The San Joaquin Valley Surface water storage and diversions such as the Friant Dam on the San Joaquin River reduce winter flooding and summer salinity of the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta.

Abandoned mines contribute toxic acid mine drainage to some tributaries of the river. Two examples exist near Coalinga, named the Atlas Asbestos Mine and the New Idria Mercury Mine, both of which is listed as superfund sites.[1] The Fresno Municipal Sanitary Landfill is also a superfund site and has been in the process of being cleaned up for 30 years.

The events at Kesterson Reservoir in the 1980s are an example of toxic levels of minerals in the San Joaquin Valley. Initially, animals and plants thrived in the artificial wetlands that were created there, but in 1983, it was found that birds had suffered severe deformities and deaths due to steadily increasing levels of chemicals and toxins. In the next few years, all the fish species died except for the mosquito fish, and algae blooms proliferated in the contaminated water.[2][3][4]

Groundwater pollution

In 1972, the California Department of Public Health commended the city of Fresno for its efforts to mitigate nitrates in the groundwater supply.[5] However, in 2001, Fresno earned a grade of poor for water quality and compliance from the Natural Resources Defense Council, an environmental advocacy group.[6] Groundwater in Fresno is unconfined and is susceptible to contamination from agriculture, runoff, and seeping contaminants. The city treats and tests the water it extracts from the ground to ensure it meets drinking water standards. Local agencies, including the cities of Fresno and Clovis, use rain water and other surface water to recharge the aquifers.[7]

Starting in 2016, some residents in Northeast Fresno complained of "red-, brown- or yellow-tinged water" in their homes, which sparked concerns about the water being unsafe for consumption. Comparisons were made to the Flint water crisis, which was happening concurrently and in the news. Two water supply experts named Marc Edwards and Vernon Snoeyink were retained to investigate and they determined that compared to Flint, "you don't have nearly the same problem (in Fresno)" and that the water complied with EPA pollution thresholds.[8] Some affected residents sued the city based on the discolored water event starting in 2016 alleging harm due to "exposure to excessive levels of lead and other toxic substances" as well as harm due to "diminution of their property value and...the cost of re-plumbing their home". The separate cases were bundled into a class action lawsuit in 2021 but a judge dismissed it the following year.[9][10]

Air pollution

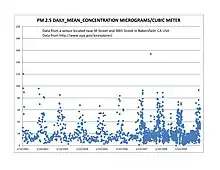

Smog (measured as Ozone) and particulate matter (measured as PM2.5) levels are very high in the San Joaquin Valley. In its 2022 survey, the American Lung Association ranked three valley metro areas as having the nation's worst short-term and year-round PM2.5 levels and only the Los Angeles metro area was ranked as having worse smog.[11]

The unique geography of the valley exacerbates the air quality problem. Residents on the valley floor are surrounded by mountain ranges which act as a pool for toxic concentrations to build up.[12]

The pollution leads to a high prevalence of asthma in the San Joaquin Valley, disproportionately affecting school-age children.[13]

Regulatory history

The primary mission of the San Joaquin Valley Air Pollution Control District is the primary regulator for the area and has taken various actions to improve air quality and meet the standards of the Clean Air Act. The District adopted a PM10 Attainment Demonstration Plan in 2006, an Ozone Attainment Demonstration Plan in 2007 and a PM2.5 Attainment Demonstration Plan in 2008. Previously, to meet California Clean Air Act requirements, the district adopted an Air Quality Attainment Plan in 1991 and then issued updates to address the California ozone standard.

Each year, measured levels of ozone and PM2.5 in the San Joaquin Valley are higher than the National Ambient Air Quality Standards established by the EPA. The PM2.5 violations typically occur in the winter months and span about 51 days.[14] Despite the violations, the EPA has taken no action on the recurring problem, leading to lawsuits.[15]

Sources

The sources of air pollutants vary and are still being researched. The ozone is believed to come from vehicles, agricultural operations, and industry, while PM2.5 is believed to comes from vehicles, power generation, industrial processes, wood burning, road and farming activities as well as wildfires. Some pollutants drift down from the Bay Area and Sacramento, including oxides of nitrogen.[16]

Burning of agricultural waste from orchards and vineyards has been a focus for regulators. The local air district's policy on agricultural burns is the strictest in the nation, only allowing agricultural burns on good air quality days. Most burning happens after the harvest, between late fall and spring.[12][17]

Natural disasters

Drought

The San Joaquin Valley is susceptible to acute periods of drought. Since water is essential to crop production, any water shortage takes a huge toll on farmers in the valley.[18] According to the California Department of Water Resources, in 2016, nine of the twelve biggest reservoirs in California are below the historical average, even after the El Nino in the winter of 2015. In the last five years, Fresno has received significantly less rainfall than the historical average of 14.77 inches per year, with the average since 2011 being 7.76 inches per year. This means that Fresno has only been getting about half of the rain that it normally does, creating problems from which it may take several years of heavy rain to recover.[19]

One obvious cause of the drought is the lack of rainfall. With significantly less rainfall than usual, small rivers have been drying up, and less water is available to farmers for their crops. Only two of the last eleven years have reached Fresno's 14.77 inch per year average, so the current drought has intensified. Several seasonal rivers and streams dependent on water releases from California's vast dam system have been dry for several years. Releasing billions of gallons of water in the spring leaves the reservoirs depleted in the hotter and drier months of the year. This is necessary to leave room for snowmelt to fill the lakes, or the reservoirs could potentially flood after heavy rainfall or unseasonable warmth. Major storms can raise the water level of the reservoirs by more than ten percent,[20] so some lakes are only allowed to reach 60 percent of capacity in winter months.[20] Also, reservoirs downstream of Fresno need to be filled to provide water for southern California, which also rarely get rain. So it becomes essential to continue releasing water from the reservoirs, even in severe drought.

Farmers depend on water to raise their crops.[21] Rain water plays an important role in the health of crops,[22] but water that is pumped into the farms through irrigation is even more important. As streams have dried up, farmers have turned to groundwater,[23] but this quickly depleted the aquifers that supply the city of Fresno, to the point where the land began to sag.[24] In the 80 years that the city of Fresno has used groundwater as a water source, the water level has dropped from 30 feet below the surface to 128 feet in 2009. This has resulted in the city of Fresno turning to alternate ways to reliably get clean water, such as aggressively recharging the ground water and occasionally purifying surface water for use by residents. This has helped to an extent, and groundwater levels have started to drop at slower rates, but more rain and runoff would help recharge them at a faster rate.

Earthquakes

The San Joaquin Valley has many geologic faults running below it. These faults can give way to large earthquakes. The largest recorded earthquakes have been the 1857 Fort Tejon earthquake and the 1952 Kern County earthquake. A smaller earthquake which affected the valley includes the 1983 Coalinga earthquake.

Floods

The San Joaquin Valley was inundated by the Great Flood of 1862, as well affected by other floods, such as in 1955 and 1964.

References

- "Toxic pollutants impacting San Joaquin River". KFSN. March 9, 2011. Archived from the original on March 13, 2011. Retrieved April 9, 2011.

- Bard, Carla (October 30, 1995). "Perspective on Pollution: Nasty Plans for Our Drinking Water: San Joaquin Valley agribusiness wants to reopen a sluice of toxic waste leading to the California Aqueduct". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 9, 2011.

- G. Fred Lee; Anne Jones-Lee (June 2006). "San Joaquin River Water Quality Issues" (PDF). G. Fred Lee. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 11, 2017. Retrieved February 28, 2023.

- Presser, Theresa S. (May 12, 2005). "Selenium Contamination Associated with Irrigated Agriculture in the Western United States". National Research Program, Water Resources Division. U.S. Geological Survey. Archived from the original on September 15, 2009. Retrieved April 9, 2011.

- "Fresno water gets states 'excellent' tag". Fresno Bee. August 24, 1972. p. A1. Retrieved January 23, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- "What's On Tap? Fresno" (PDF). 2002. Retrieved November 14, 2016.

- "Groundwater Recharge". Fresno Metropolitan Flood Control District. Retrieved January 23, 2023.

- Sheehan, Tim (August 20, 2016). "Expert: Red water part of galvanized pipe; some lead fears overblown". The Fresno Bee. Archived from the original on August 21, 2016. Retrieved September 17, 2022.

- "Northeast Fresno homeowners allowed to sue city over 'tainted' water in homes". August 5, 2021. Retrieved September 17, 2022.

- Taub, David (September 29, 2022). "Judge Rules in City's Favor in Northeast Fresno Rusty Water Case". Retrieved January 23, 2023.

- "State of the Air 2022". American Lung Association. Archived from the original on February 6, 2023. Retrieved February 6, 2023.

- Briscoe, Tony (June 11, 2022). "Air quality worsens as drought forces California growers to burn abandoned crops". LA Times. Archived from the original on June 12, 2022. Retrieved February 21, 2022.

- Rondero Hernandez V, Sutton P, Curtis KA, Carabez R (2004). "Struggling to breathe: The epidemic of asthma among children and adolescents in the San Joaquin Valley" (PDF). California State University, Fresno. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 14, 2022. Retrieved February 21, 2023.

- Chen J, Lu J, Avise J, DaMassa J, Kleeman M, Kaduwela A (August 2014). "Seasonal modeling of PM2.5 in California's San Joaquin Valley". Atmospheric Environment. 92: 182–190. doi:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2014.04.030.

- "Several groups sue EPA over unhealthy San Joaquin Valley air". The Fresno Bee. November 12, 2021. p. A1. Retrieved February 20, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- Purtill, Corinne (April 22, 2007). "Calif. offers blueprint for cleaner air". Arizona Republic. pp. A1, A22. Retrieved February 28, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- Price, Larry C. (December 3, 2018). "In California's Fertile Valley, Industry and Agriculture Hang Heavy in the Air". Undark Magazine. Archived from the original on May 14, 2021. Retrieved February 23, 2023.

- James, Ian (February 25, 2022). "California agriculture takes $1.2-billion hit during drought, losing 8,700 farm jobs, researchers find". Los Angeles Times.

- Bland, Alastair (January 12, 2023). "Is California's drought over? Here's what you need to know about rain, snow, reservoirs and drought". CalMatters.

- Sommer, L. (n.d.). California Reservoirs Are Dumping Water in a Drought, But Science Could Change That. Retrieved January 16, 2023

- Water and agriculture: Managing water sustainably is key to the future of food and agriculture, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

- How Does Drought Affect Our Lives?, National Drought Mitigation Center, School of Natural Resources, University of Nebraska

- Burlig, Fiona (July 30, 2019). "Amid Climate-Linked Drought, Farmers Turn To New Water Sources. Those Are Drying Up Too". Energy Policy Institute at the University of Chicago.

- Miller, Thaddeus (January 7, 2020). "Valley land has sunk from too much water pumping. Can Fresno County fix it?". Fresno Bee.