Manuel II Palaiologos

Manuel II Palaiologos or Palaeologus (Greek: Μανουὴλ Παλαιολόγος, romanized: Manouēl Palaiológos; 27 June 1350 – 21 July 1425) was Byzantine emperor from 1391 to 1425. Shortly before his death he was tonsured a monk and received the name Matthew. His wife Helena Dragaš saw to it that their sons, John VIII and Constantine XI, became emperors. He is commemorated by the Greek Orthodox Church on July 21.[2]

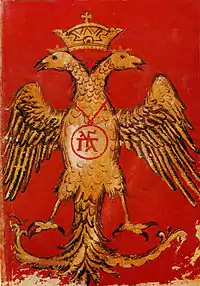

| Manuel II Palaiologos | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emperor and Autocrat of the Romans | |||||

.jpg.webp) Miniature portrait of Manuel II, 1407–1409[1] | |||||

| Byzantine emperor | |||||

| Reign | 16 February 1391 – 21 July 1425 | ||||

| Coronation | 25 September 1373 | ||||

| Predecessor | John V Palaiologos | ||||

| Successor | John VIII Palaiologos | ||||

| Born | 27 June 1350 Constantinople, Byzantine Empire (present day Istanbul, Turkey) | ||||

| Died | 21 July 1425 (aged 75) Constantinople, Byzantine Empire | ||||

| Spouse | Helena Dragaš | ||||

| Issue more... | John VIII Palaiologos Theodore II Palaiologos Andronikos Palaiologos Constantine XI Palaiologos Demetrios Palaiologos Thomas Palaiologos | ||||

| |||||

| House | Palaiologos | ||||

| Father | John V Palaiologos | ||||

| Mother | Helena Kantakouzene | ||||

| Religion | Eastern Orthodox | ||||

Life

Manuel II Palaiologos was the second son of Emperor John V Palaiologos and his wife Helena Kantakouzene.[3] Granted the title of despotēs by his father, the future Manuel II traveled west to seek support for the Byzantine Empire in 1365 and in 1370, serving as governor in Thessalonica from 1369. The failed attempt at usurpation by his older brother Andronikos IV Palaiologos in 1373 led to Manuel's being proclaimed heir and co-emperor of his father. He was crowned on 25 September 1373.[4]

In 1376–1379 and again in 1390, Manuel and his father were supplanted by Andronikos IV and then his son John VII, but Manuel personally defeated his nephew with help from the Republic of Venice in 1390. Although John V had been restored, Manuel was forced to go as an honorary hostage to the court of the Ottoman Sultan Bayezid I at Prousa (Bursa). During his stay, Manuel was forced to participate in the Ottoman campaign that reduced Philadelpheia, the last Byzantine enclave in Anatolia.

Siege of Constantinople and letters to European courts

Having heard of his father's death in February 1391, Manuel II Palaiologos fled the Ottoman court and secured the capital against any potential claim by his nephew John VII.[5] Following Manuel's coronation the Ottoman Sultan was initially content to leave Byzantium in comparative peace. However, in 1393 a large insurrection erupted in Bulgaria which, although successfully put down by the Ottomans, caused Bayezid to lapse into an episode of paranoia in which he believed his various Christian vassals were plotting against him. Bayezid called all his Christian vassals to a meeting at Serres, with the intention of massacring them, a decision he relented on only at the last moment. The episode is said to have left all of the Christian vassal rulers shaken and convinced Manuel that continued appeasement towards the Ottomans was not a guarantee of his own personal safety or the continued survival of the empire and that efforts must be made to obtain Western aid.[6]

Sultan Bayezid I blockaded Constantinople from 1394 to 1402. In the meantime, an anti-Ottoman crusade led by the Hungarian King Sigismund of Luxemburg failed at the Battle of Nicopolis on 25 September 1396. Manuel II had sent 10 ships to help in that Crusade. In October 1397, Theodore Kantakouzenos, Manuel's uncle, alongside John of Natala arrived at the court of Charles VI of France, bearing the Emperor's letters (dated 1 July 1397) requesting the French king's military aid. In addition, Charles also provided funds for the two nobles to treat with King Richard II of England in April 1398, with the aim of soliciting further aid.[7] Though the latter was preoccupied by domestic troubles at this point to provide any support.[lower-alpha 1]

However, the two nobles returned home with the Marshal of France Jean II Le Maingre who was sent from Aigues-Mortes with six ships carrying 1,200 men to assist Manuel II. The Marshal encouraged the latter to go personally to seek assistance against the Ottoman Empire from the courts of western Europe. After some five years of siege, Manuel II entrusted the city to his nephew, aided by a French garrison of 300 men led by Seigneur Jean de Châteaumorand and embarked (along with a suite of 40 people) on a long trip abroad along with the Marshal.[8]

Emperor's trip to the West

On 10 December 1399, Manuel II sailed to the Morea, where he left his wife and children with his brother Theodore I Palaiologos to be protected from his nephew's intentions. He later landed in Venice in April 1400, then he went to Padua, Vicenza and Pavia, until he reached Milan, where he met Duke Gian Galeazzo Visconti, and his close friend Manuel Chrysoloras. Afterwards, he met Charles VI of France at Charenton on 3 June 1400.[9] During his stay in France, Manuel II continued to contact European monarchs.[10]

According to Michel Pintoin who chronicled the visit to Paris:

Then, the king raised his hat, and the emperor raised his imperial cap – he had no hat – and both greeted one another in the most honourable way. When he had welcomed [the emperor], the king accompanied him into Paris, riding side by side. They were followed by the Princes of the Blood who, once the banquet in the royal palace finished, escorted [the emperor] to the lodgings which had been prepared for him in the Louvre castle].

— [11]

In December 1400, he embarked to England to meet Henry IV of England who received him at Blackheath on the 21st of that month,[10] making him the only Byzantine emperor ever to visit England, where he stayed at Eltham Palace until mid-February 1401, and a joust took place in his honour.[13] In addition, he received £2,000, in which he acknowledged receipt of the funds in a Latin document and sealed it with his own golden bull.[14][lower-alpha 2]

Thomas Walsingham wrote about Manuel II's visit to England:

At the same time the Emperor of Constantinople visited England to ask for help against the Turks. The king with an imposing retinue, met him at Blackheath on the feast of St Thomas [21 December], gave so great a hero an appropriate welcome and escorted him to London. He entertained him there royally for many days, paying the expenses of the emperor's stay, and by grand presents showing respect for a person of such eminence.

— [15]

Moreover, Adam of Usk reported:

On the feast of St Thomas the apostle [21 December], the emperor of the Greeks visited the king of England in London to seek help against the Saracens, and was honourably received by him, staying with him for two whole months at enormous expense to the king, and being showered with gifts at his departure. This emperor and his men always went about dressed uniformly in long robes cut like tabards which were all of one colour, namely white, and disapproved greatly of the fashions and varieties of dress worn by the English, declaring that they signified inconstancy and fickleness of heart. No razor ever touched the heads or beards of his priests. These Greeks were extremely devout in their religious services, having them chanted variously by knights or by clerics, for they were sung in their native tongue. I thought to myself how sad it was that this great Christian leader from the remote east had been driven by the power of the infidels to visit distant islands in the west in order to seek help against them.

— [16]

However, Manuel II sent a letter to his friend Manuel Chrysoloras, describing his visit to England:

Now what is the reason for the present letter? A large number of letters have come to us from all over bearing excellent and wonderful promises, but most important is the ruler with whom we are now staying, the king of Britain the Great, of a second civilized world, you might say, who abounds in so many good qualities and is adorned with all sorts of virtues. His reputation earns him the admiration of people who have not met him, while for those who have once seen him, he proves brilliantly that Fame is not really a goddess, since she is unable to show the man to be as great as does actual experience. This ruler, then, is most illustrious because of his position, most illustrious too, because of his intelligence; his might amazes everyone, and his understanding wins him friends; he extends his hand to all and in every way he places himself at the service of those who need help. And now, in accord with his nature, he has made himself a virtual haven for us in the midst of a twofold tempest, that of the season and that of fortune, and we have found refuge in the man himself and his character. His conversation is quite charming; he pleases us in every way; he honours us to the greatest extent and loves us no less. Although he has gone to extremes in all he has done for us, he seems almost to blush in the belief—in this he is alone—that he might have fallen considerably short of what he should have done. This is how magnanimous the man is.

— [17]

Manuel II later returned to France with high hopes of substantial help and funds for Constantinople. In the meantime, he sent delegations with relics including pieces of the tunic of Christ and a piece of the Holy Sponge to Pope Boniface IX and Antipope Benedict XIII, Queen Margaret I of Denmark, king Martin of Aragon and king Charles III of Navarre to seek further assistance.[18][19] He eventually left France on 23 November 1402,[20] and finally returned to Constantinople in June 1403.

Renewed Ottoman sieges

The Ottomans under Bayezid I were themselves crushingly defeated by Timur at the Battle of Ankara in 1402. As the sons of Bayezid I struggled with each other over the succession in the Ottoman Interregnum, John VII was able to secure the return of the European coast of the Sea of Marmara and of Thessalonica to the Byzantine Empire in the Treaty of Gallipoli. When Manuel II returned home in 1403, his nephew duly surrendered control of Constantinople and received as a reward the governorship of newly recovered Thessalonica. The treaty also regained from the Ottomans Mesembria (1403–1453), Varna (1403–1415), and the Marmara coast from Scutari to Nicomedia (between 1403–1421).

However, Manuel II kept contact with Venice, Genoa, Paris and Aragon, by sending envoy Manuel Chrysoloras in 1407–8, pursuing to form a coalition against the Ottomans.[21]

On 25 July 1414, with a fleet consisting of four galleys and two other vessels carrying contingents of infantry and cavalry, departed Constantinople for Thessalonica. The purpose of this force soon became clear when he made an unannounced stop at Thasos, a normally unimportant island which was then under threat from a son of the lord of Lesbos, Francesco Gattilusio. It took Manuel three months to reassert imperial authority on the island. Only then did he continue on to Thessalonica, where he was warmly met by his son Andronicus, who then governed the city.

In the spring of 1415, he and his soldiers left for the Peloponnese, arriving at the little port of Kenchreai on Good Friday, 29 March. Manuel II Palaiologos used his time there to bolster the defences of the Despotate of Morea, where the Byzantine Empire was actually expanding at the expense of the remnants of the Latin Empire. Here Manuel supervised the building of the Hexamilion (six-mile wall) across the Isthmus of Corinth, intended to defend the Peloponnese from the Ottomans.

Manuel II stood on friendly terms with the victor in the Ottoman civil war, Mehmed I (1402–1421), but his attempts to meddle in the next contested succession led to a new assault on Constantinople by Murad II (1421–1451) in 1422. During the last years of his life, Manuel II relinquished most official duties to his son and heir John VIII Palaiologos, and went back to the West searching for assistance against the Ottomans, this time to the King Sigismund of Hungary, staying for two months in his court of Buda. Sigismund (after suffering a defeat against the Turks in the Battle of Nicopolis in 1396) never rejected the possibility of fighting against the Ottoman Empire. However, with the Hussite wars in Bohemia, it was impossible to count on the Czech or German armies, and the Hungarian ones were needed to protect the Kingdom and control the religious conflicts.[22] Unhappily Manuel returned home with empty hands from the Hungarian Kingdom, and in 1424 he and his son were forced to sign an unfavourable peace treaty with the Ottoman Turks, whereby the Byzantine Empire had to pay tribute to the sultan.

Death

Manuel II was paralyzed by a stroke on 1 October 1422, but his mind was unaffected and he continued to rule for three more years. He lived his last few days as a monk, taking the name of Matthew. He died on 21 July 1425, aged 75, and was buried at the Pantokrator Monastery in Constantinople.[23][24]

Writings

Manuel II was the author of numerous works of varied character, including letters, poems, a Saint's Life, treatises on theology and rhetoric, and an epitaph for his brother Theodore I Palaiologos and a mirror of princes for his son and heir John. This mirror of princes has special value, because it is the last sample of this literary genre bequeathed to us by Byzantines.

Family

By his wife Helena Dragas, the daughter of the Serbian prince Constantine Dragas, Manuel II Palaiologos had several children, including:

- A daughter. Mentioned as the eldest daughter but not named.

- Constantine Palaiologos. Born c. 1393/8, died before 1405 in Monemvasia.[26]

- John VIII Palaiologos (18 December 1392 – 31 October 1448). Byzantine emperor, 1425–1448.

- Andronikos Palaiologos, Lord of Thessalonica (d. 1429).

- A second daughter. Also not named in the text.

- Theodore II Palaiologos, Lord of Morea (d. 1448).

- Michael Palaiologos. Born 1406/7, died 1409/10 of the plague.[27]

- Constantine XI Dragases Palaiologos (8 February 1405 – 29 May 1453). Despotēs in the Morea and subsequently the last Byzantine emperor, 1448–1453.

- Demetrios Palaiologos (c. 1407–1470). Despotēs in the Morea.

- Thomas Palaiologos (c. 1409 – 12 May 1465). Despotēs in the Morea.

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Manuel II Palaiologos | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Pope Benedict XVI controversy

In a lecture delivered on 12 September 2006, Pope Benedict XVI quoted from a dialogue believed to have occurred in 1391 between Manuel II and a Persian scholar and recorded in a book by Manuel II (Dialogue 7 of Twenty-six Dialogues with a Persian) in which the Emperor stated: "Show me just what Muhammad brought that was new and there you will find things only evil and inhuman, such as his command to spread by the sword the faith he preached."

Gallery

See also

Notes

- In addition, Ilario Doria, Manuel's son-in-law, was also sent with a delegation to Italy, England, and probably France, early in 1399.[7]

- King Richard II had collected the same sum to be sent to Constantinople, yet it had never passed through the bank in Genoa, despite a later investigation by Henry IV.[14]

References

- Evans, Helen C., ed. (2004). Byzantium: Faith and Power (1261-1557). Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 26. ISBN 978-1-58839-113-1.

- Great Synaxaristes: (in Greek) Ὁ Ὅσιος Μανουὴλ Αὐτοκράτωρ Κωνσταντινουπόλεως. 21 Ιουλίου. ΜΕΓΑΣ ΣΥΝΑΞΑΡΙΣΤΗΣ.

- Barker 1969, p. xix.

- Norwich 1995, p. 337.

- Barker 1969, p. xxiv.

- Norwich 1995, pp. 351–354.

- Hinterberger & Schabel 2011, p. 397.

- Hinterberger & Schabel 2011, p. 398.

- Hinterberger & Schabel 2011, p. 398–399.

- Hinterberger & Schabel 2011, p. 402.

- Sobiesiak, Tomaszek & Tyszka 2018, pp. 74–75.

- "St Alban's chronicle". p. 245.

- Brian Cathcart An emperor in Eltham New Statesman 25 September 2006. The Latin Emperor of Constantinople, Baldwin II, visited the court of Henry III on two occasions, in 1238 and 1247, in search of assistance against the Byzantine successor state of Nicaea. Cf. Matthew Paris, Chronica Majora, ed. H.R. Luard, London: 1872–1883, 7 vols. (Rolls series, 57): vol. 3, 480–481; vol. 4, 625–626.

- Nicol 1974, p. 198.

- Walsingham 2005, p. 319.

- Adam of Usk 1997, pp. 119–121.

- Dennis 1977, p. 102.

- Voordeckers 2006, p. 271.

- Hinterberger & Schabel 2011, p. 403.

- Hinterberger & Schabel 2011, p. 411.

- Çelik 2021, p. 260.

- Szalay, J. y Baróti, L. (1896). A Magyar Nemzet Története. Budapest, Hungría: Udvari Könyvkereskedés Kiadó.

- Norwich 1995, p. 387.

- Melvani, N., (2018) 'The tombs of the Palaiologan emperors', Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies, 42 (2) pp.237-260

- Spatharakis, Ioannis (1976), The Portrait in Byzantine Illuminated Manuscripts, Brill, p. 139, ISBN 9789633862971

- Trapp, Erich; Beyer, Hans-Veit; Kaplaneres, Sokrates; Leontiadis, Ioannis (1989). "21490. Παλαιολόγος Κωνσταντῖνος". Prosopographisches Lexikon der Palaiologenzeit (in German). Vol. 9. Vienna: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften. ISBN 3-7001-3003-1.

- Trapp, Erich; Beyer, Hans-Veit; Kaplaneres, Sokrates; Leontiadis, Ioannis (1989). "21520. <Παλαιολόγος> Μιχαήλ". Prosopographisches Lexikon der Palaiologenzeit (in German). Vol. 9. Vienna: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften. ISBN 3-7001-3003-1.

Sources

- Adam of Usk (1997). Chris Given-Wilson (ed.). The Chronicle of Adam Usk, 1377-1421. Clarendon Press. ISBN 9780198204831.

- Barker, John W. (1969). Manuel II Palaeologus (1391-1425): A Study in Late Byzantine Statesmanship. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 9780813505824.

- Çelik, Siren (2021). Manuel II Palaiologos (1350–1425). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781108836593.

- Dennis, George T. (1977). The letters of Manuel II Palaeologus. Dumbarton Oaks. ISBN 9780884020684.

- Hinterberger, Martin; Schabel, Chris (2011). Greeks, Latins, and Intellectual History 1204-1500 (PDF). Peeters.

- Nicol, Donald M. (1993). The Last Centuries of Byzantium, 1261-1453. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521439916.

- Norwich, John Julius (1995). Byzantium: The Decline and Fall. London: Viking. ISBN 978-0-670-82377-2.

- Nicol, Donald M. (1974). "Byzantium and England". Institute for Balkan Studies.

- Sobiesiak, Joanna Aleksandra; Tomaszek, Michał; Tyszka, Przemysław (2018). Andrzej Pleszczyński (ed.). Imagined Communities: Constructing Collective Identities in Medieval Europe. Brill. ISBN 9789004352476.

- Walsingham, Thomas (2005). James G. Clark; David Preest (eds.). The Chronica Maiora of Thomas Walsingham, 1376-1422. Boydell Press. ISBN 9781843831440.

- Voordeckers, Edmond (2006). Byzantion. University Foundation.

Further reading

- Manuel II Palaeologus Funeral Oration on His Brother Theodore. J. Chrysostomides (editor & translator). Association for Byzantine Research: Thessalonike, 1985.

- Manuel II Palaeologus, The Letters of Manuel II Palaeologus George T. Dennis (translator), Dumbarton Oaks, 1977. ISBN 0-88402-068-1.

- Çelik, Siren (2021). Manuel II Palaiologos (1350-1425): A Byzantine Emperor in a Time of Tumult. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1108836593

- Karl Förstel (ed.): Manuel II. Palaiologos: Dialoge mit einem Muslim (Corpus Islamo-Christianum. Series Graeca 4). 3 vol. Echter Verlag, Würzburg 1995; ISBN 3-89375-078-9, ISBN 3-89375-104-1, ISBN 3-89375-133-5 (Greek Text with German translation and commentary).

- Jonathan Harris, The End of Byzantium. Yale University Press, 2010. ISBN 978-0-300-11786-8

- Florin Leonte, Rhetoric in Purple: The Renewal of Imperial Ideology in the Texts of Manuel II Palaiologos. PhD dissertation, Central European University, Budapest, 2012

- Leonte, Florin (2012), Rhetoric in purple : the renewal of imperial ideology in the texts of emperor Manuel II Palaiologos, CEU ETD collection

- Mureşan, Dan Ioan (2010). "Une histoire de trois empereurs. Aspects des relations de Sigismond de Luxembourg avec Manuel II et Jean VIII Paléologue". In Ekaterini Mitsiou; et al. (eds.). Sigismund of Luxemburg and the Orthodox World (Veröffentlichungen zur Byzanzforschung, 24). Wien: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften. pp. 41–101. ISBN 978-3-7001-6685-6

- Necipoglu, Nevra (2009). Byzantium between the Ottomans and the Latins: Politics and Society in the Late Empire. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-511-51807-2.

- Nicol, Donald M. (1996). The Reluctant Emperor: A Biography of John Cantacuzene, Byzantine Emperor and Monk, c. 1295-1383. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521522014.

- George Sphrantzes. The Fall of the Byzantine Empire: A Chronicle by George Sphrantzes, 1401–1477. Marios Philippides (editor & translator). University of Massachusetts Press, 1980. ISBN 0-87023-290-8.

- Erich Trapp: Manuel II. Palaiologos: Dialoge mit einem „Perser“. Verlag Böhlau, Wien 1966, ISBN 3-7001-0965-2. (German)

- Athanasios D. Angelou, Manuel Palaiologos, Dialogue with the Empress - Mother on Marriage. Introduction, Text and Translation, Vienna, Academie der Wissenschaft, Vienna 1991.

- Shukurov, Rustam (2016). "The Byzantine Turks (1204-1461)". The Byzantine Turks, 1204-1461. Leiden: Brill: 421. doi:10.1163/9789004307759_013.

External links

- Encyclopedia of Roman Emperors entry

- Manuel Palaeologos Resources, including excerpts from his writings to his son John, on "the virtue of a king"

- Historical contemporary references to Manuel II (in Greek) by the Byzantine Greek historian George Sphrantzes

- Portraits of Manuel II

- Dialogue 7 with a learned Persian – chapters 1–18 only.