E. C. Segar

Elzie Crisler Segar (/ˈsiːɡɑːr/;[1] December 8, 1894 – October 13, 1938), known by the pen name E. C. Segar, was an American cartoonist best known as the creator of Popeye, a pop culture character who first appeared in 1929 in Segar's comic strip Thimble Theatre.[2][3]

| E. C. Segar | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Elzie Crisler Segar December 8, 1894 Chester, Illinois, U.S. |

| Died | October 13, 1938 (aged 43) Santa Monica, California, U.S. |

| Area(s) | Cartoonist |

Notable works | Popeye (1929–1938) |

Charles M. Schulz said of Segar's work: "I think Popeye was a perfect comic strip, consistent in drawing and humor".[4] Carl Barks described Segar as "the unbridled genius as far as I was concerned".[5]

Early life

Segar was born on December 8, 1894, and raised in Chester, Illinois, a small town near the Mississippi River.[2][6][7] The son of Jewish parents Erma Irene (Crisler) and Amzi Andrews Segar, a handyman,[8] his earliest work experiences included assisting his father in house painting and paper hanging.[9] Skilled at playing drums, he also provided musical accompaniment to films and vaudeville acts in the local theater, where he was eventually given the job of film projectionist[10] at the Chester Opera House, where he also did live performances.[6] At age 18, he decided to become a cartoonist. He took a correspondence course in cartooning from W. L. Evans of Cleveland, Ohio.[10] He said that after work he "lit up the oil lamps about midnight and worked on the course until 3 a.m." During this time, Segar also began studying the work of cartoonists that he would later cite as influences on his work, including Rube Goldberg, George McManus and George Herriman (especially Herriman's strip Stumble Inn).[2][3][7][11]

Asked how to say his name, he told The Literary Digest it was "SEE-gar".[1] He commonly signed his work simply Segar or E. Segar above a drawing of a cigar.

Early work

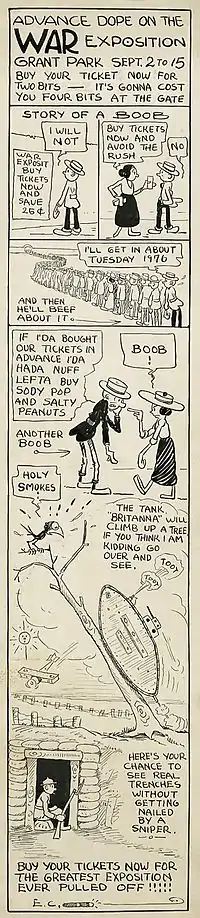

Segar moved to Chicago, Illinois, where he met Richard F. Outcault, the creator of The Yellow Kid and Buster Brown. Outcault encouraged him and introduced him at the Chicago Herald.[2] On March 12, 1916, the Herald published Segar's first comic, Charlie Chaplin's Comic Capers, which ran for a little over a year. In 1917, Segar created Barry the Boob, about an incompetent soldier. Segar also originated two other, short-lived comics for the Herald's Sunday magazine. These were The Mistakes of Mr. Muddle and the Rube Goldberg-inspired And They Get By With It.[3] In 1918, he moved on to William Randolph Hearst's Chicago Evening American, for which he created Looping the Loop and worked as a second-string drama critic.[7][12] Looping the Loop was a comic strip that gave a whimsical take on the events in Chicago's "Loop" district. "Looping the Loop" made jokes about such issues as silent movies, plays, and the changing seasons; it proved popular with the Herald's readers.[7] Segar married Myrtle Johnson that year; they had two children. In October 1919, Segar covered that year's World Series, creating eight cartoons for the sports pages.[13][14]

Thimble Theatre, Sappo and Popeye

Evening American managing editor William Curley thought Segar could succeed in New York, so he sent him to King Features Syndicate, where Segar worked for many years. King Features asked Segar to create a comic strip to replace Midget Movies by Ed Wheelan, who had recently resigned from the syndicate.[15] Segar created Thimble Theatre for the New York Journal, as the replacement for Wheelan's strip. The Thimble Theatre strip made its debut on December 19, 1919, featuring the characters Olive Oyl, Castor Oyl and Harold Hamgravy, whose name was quickly shortened in the strip to simply "Ham Gravy". They were the strip's leads for about a decade.[2] Segar began writing long storylines or "continuities" for Thimble Theatre in 1922. In these, the characters would have lengthy adventures in Africa and the Wild West.[16] In one storyline, the characters encountered a superhuman "tough guy" named Harry Hardegg, who was able to break a moving buzz saw with his head. Comics historian Bill Blackbeard has described Harry Hardegg as a "prototype" for Popeye.[16]

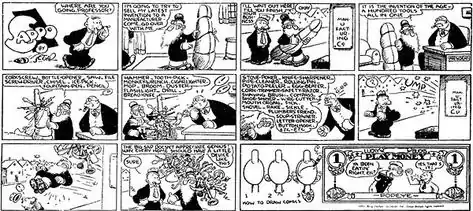

Segar also created The Five-Fifteen for King Features in 1920; it was retitled Sappo in 1926, although numerous newspapers had already retitled the strip 'Sappo the Commuter' by 1924. The Five-Fifteen started its run as a Monday-through-Saturday strip, concluding its initial daily run in February 1925. In 1926, the strip, now officially retitled, was revived as a Sunday-only topper to the Thimble Theatre Sunday pages. Initially, this strip revolved about the exploits of suburban couple John and Myrtle Sappo. In May 1932, however, Segar introduced the eccentric scientist and inventor (and self-proclaimed "genius") O.G. Wotasnozzle into the strip as a regular. Wotasnozzle's bizarre machines soon became the focus of the strip, with John Sappo frequently cast as his test subject and straight man.[2][17]

On January 17, 1929, when Castor Oyl needed a mariner to navigate his ship to Dice Island, Castor picked up a weatherbeaten sailor named Popeye in the docks. Popeye's first line in the strip, upon being asked if he was a sailor, was "'Ja think I'm a cowboy?"[18] At first Segar intended Popeye to be a once-off character, but after large numbers of newspaper readers wrote in requesting the character's return, Segar reintroduced Popeye as a full-time regular in August 1929, eventually enabling the sailor to become the focal point of the strip.[3] Segar initially depicted Popeye as a quarrelling antihero.[2] Segar's storylines for the Popeye-focused Thimble Theatre drew on several fictional genres, including Westerns, pirate swashbucklers, Sports stories, and fantasy stories.[2][3] Some of the other notable characters Segar created include J. Wellington Wimpy and Eugene the Jeep.[2]

In 1929, Segar and his friend, screenwriter Norton S. Parker, began work on The Sea Hag, a prose novel for adults that would have featured both Popeye and the villainess the Sea Hag. However, King Features refused to grant Segar and Parker permission to publish the novel. The Sea Hag has never been put into print.[16]

In 1934, King Features (noting the increasing popularity of the Popeye character with children) ordered Segar to tone down Popeye's swearing and brawling.[16] Although irritated by the order, Segar complied, and made Popeye more of a straightforward hero, more ubiquitously emphasizing his already-established affinity for aiding children and animals rather than his more violent and irascible tendencies, which persisted in a somewhat reduced form.[2][16] Segar continued to produce Thimble Theatre, published in five hundred newspapers globally by 1938, until his death. Beginning in 1933, Popeye was adapted into a series of cartoons by the Fleischer Studios, which exponentially increased the character's already-ascendant popularity further.[2] Popeye was also licensed by King Features for hundreds of toys, games and other products.[2] The commercial success of these products ensured King Features paid Segar highly for his work; by 1938, the syndicate was giving Segar a salary of $100,000 a year.[2]

Later life and death

Segar and his family later moved to Santa Monica, California. According to Segar's assistant, Bud Sagendorf, Segar lived near George Herriman. However, although the two cartoonists admired each other's work, they never visited each other in this period.[2] After prolonged illness, Segar died of leukemia and liver disease in October 1938 at the age of 43.[19]

Legacy and reprints

Segar was among the first cartoonists to combine humorous situations with long-running adventures.[2]

Comics creators who cited E.C. Segar's work as an influence included Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, Boody Rogers, Charles M. Schulz, Carl Barks, Robert Crumb, and Stephen Hillenburg.[20][21][22]

A revival of interest in Segar's creations began with Woody Gelman's Nostalgia Press. Robert Altman's live-action film Popeye (1980) is adapted from E. C. Segar's Thimble Theatre comic strip. The screenplay by Jules Feiffer was based directly on Gelman's Thimble Theatre Starring Popeye the Sailor, a hardcover reprint collection of 1936–37 Segar strips published in 1971 by Nostalgia Press.[23] In 2006, Fantagraphics published the first of a six-volume book set reprinting all Thimble Theatre daily and Sunday strips from 1928 to 1938, beginning with the adventure that introduced Popeye.

In 1971, the National Cartoonists Society created the Elzie Segar Award in his honor. According to the Society's website, the award was "presented to a person who has made a unique and outstanding contribution to the profession of cartooning." The NCS board of directors chose the first winners, while King Features selected recipients in later years. Honorees have included Charles Schulz, Bil Keane, Al Capp, Bill Gallo and Mort Walker. The award was discontinued in 1999.[24]

In 2012, cartoonists Roger Langridge and Bruce Ozella teamed to revive the spirit of Segar in a 12-issue limited series, Popeye, published by IDW.

In 2018, Sunday Press Books published Thimble Theatre & The Pre-Popeye Comics of E.C. Segar, collecting Segar's early comic strip work,[25] primarily the Thimble Theatre Sunday pages published between 1925 and 1930.

Timeline

| Title | Start date | End date |

|---|---|---|

| Charlie Chaplin's Comic Capers | March 1916 | April 1917 |

| The Mistakes of Mr. Muddle | March 1917 ? | April 1918 |

| And They Get By With It | March 1917 ? | April 1918 |

| Barry the Boob | April 1917 | April 1918 |

| Looping the Loop | June 1918 | December 1919 |

| Thimble Theatre (Popeye) | December 1919 | October 1938 |

| The Five-Fifteen (Sappo) | December 1920 | October 1938 |

Popeye & Friends Character Trail

In 1977, Segar's hometown of Chester, Illinois, named a park in his honor. The park contains a six-foot-tall bronze statue of Popeye. The annual Popeye Picnic, a weekend-long event that celebrates the character with a parade, film festival and other activities, is held the first weekend after Labor Day.[26] In 2006, Chester launched the "Popeye & Friends Character Trail", which links a series of statues of Segar's characters located throughout town.[27] Each stands on a base inscribed with the names of donors who contributed to its cost and is unveiled and dedicated during the Popeye Picnic. The 2006 debut sculpture of hamburger-loving Wimpy stands in Gazebo Park. A statue of Olive Oyl, Swee'Pea and the Jeep, located near the Randolph County Courthouse, followed in 2007. In 2008, a Bluto statue was dedicated at the corner of Swanwick and W. Holmes Streets, in front of Buena Vista Bank. The 2009 statue of Castor Oyl and Bernice the Whiffle Hen stands in front of Chester Memorial Hospital. One additional statue has been unveiled each year.

| Year | Character(s) | Location |

|---|---|---|

| 2010 | SeaHag/Bernard | McDonald's/Walmart |

| 2011 | Cole Oyl | Chester Public Library |

| 2012 | Alice the Goon | Chester Center |

| 2013 | Poopdeck Pappy | Cohen Complex |

| 2014 | Prof. Watasnozzle | Chester High School |

| 2015 | RoughHouse | Reids' Harvest House |

| 2016 | Nephews-Peepeye/Poopeye/Pipeye/Pupeye | Chester Grade School |

| 2017 | King Blozo | Chester City Hall |

| 2018 | Nana Oyl | Manor at Craig's Farm |

| 2019 | Popeye's Pups | Chester Firehouse |

| 2019 | Sherlock & Segar | Baskerville Hall on Swanwick Street |

| 2020 | Toar | St Nicholas Landmark |

| 2021 | Harold Hamgravy | Randolph County Courthouse |

Spinach Can Collectibles/Popeye Museum is located in the center of the city.(Opera House)[28]

On December 8, 2009, Google celebrated Segar's 115th birthday with a Google Doodle of Popeye. The doodle used Popeye's body as the 'g', had 'oogl', drawn to resemble Segar's drawing style, and a spinach can as the 'e', and featured Popeye punching the 'oogl' to cause the spinach to fly at him through the air.

References

- Funk, Charles Earle. What's the Name, Please?, Funk & Wagnalls, 1936.

- "E. C. Segar", in Walker, Brian. The Comics: The Complete Collection. New York: Abrams ComicArts, 2011. (pp. 238–243) ISBN 9780810995956

- "E. C. Segar", in Tumey, Paul C. Screwball! : The Cartoonists Who Made The Funnies Funny. San Diego : IDW Publishing, 2019 ISBN 9781684051878 (pp. 158-179)

- Mendelson, Lee and Schulz, Charles M., Charlie Brown and Charlie Schulz: in celebration of the 20th anniversary of "Peanuts". New York: New American Library, 1971. (p. 35)

- Barks, Carl, and Ault, Donald D. Carl Barks : conversations. Jackson : University Press of Mississippi, 2003 ISBN 9781578065011 (p. 133).

- Grandinetti 2004, p. 2.

- O'Sullivan, Judith. The Great American Comic Strip.Boston : Little, Brown and Company, 1990. ISBN 9780821217566 (p.186-187)

- Reynolds, Moira Davison (October 2, 2015). Comic Strip Artists in American Newspapers, 1945-1980. ISBN 9780786481507.

- "The Secret Jewish History of Popeye the Sailor Man". May 31, 2019.

- Gabbatt, Adam (December 8, 2009). "E.C. Segar, Popeye's creator, celebrated with a Google doodle". London: Guardian. Retrieved May 12, 2011.

- "Among the most enthusiastic fans of Herriman's new strip was the cartoonist E. C. Segar...Cartoonist Bud Sagendorf, who assisted Segar and eventually took over Popeye, credited Stumble Inn as a primary inspiration. "With that, you can see where Segar took his whole style out of," said Sagendorf." Tisserand, Michael. Krazy : George Herriman, a life in black and white. New York, NY : Harper Perennial, 2018 ISBN 9780061733000 (p.320).

- "Cartoonist Segar, Popeye Creator (Obituary)". The New York Times. Associated Press. October 14, 1938. p. 23. Retrieved October 6, 2015 – via ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- "The Early Works of E.C. Segar". Archived from the original on November 10, 2013. Retrieved June 24, 2012.

- "The Thimble Theatre Comic Strip starring Popeye". Archived from the original on November 8, 2012. Retrieved June 24, 2012.

- Clark, Alan and Laurel. Comics: An Illustrated History. London, Green Wood Publishing, 1992. ISBN 9781872532554 (p.54)

- "E.C. Segar's Knockouts of 1925 (and Low Blows Before and After) : The Unknown Thimble Theatre Period" in NEMO :The Classic Comics Library no. 3, October 1983 (pgs. 6-25).

- Donald Phelps, Reading the Funnies: Essays on Comic Strips. Seattle, Wash. : Fantagraphics Books, 2001. ISBN 9781560973683 (pp.52-3)

- Coulton Waugh, The Comics. New York, Luna Press, 1974. ISBN 9780914466031 (p.117)

- "Ed Black's Cartoon Flashback". Ncs-glc.com. Archived from the original on May 16, 2011. Retrieved May 12, 2011.

- "The influences on Superman were numerous. The ones that Siegel and Shuster admitted to included... E. C. Segar's Popeye (for his superstrength)." Nevins, Jess. The Evolution of the Costumed Avenger : The 4,000-year History of the Superhero. Santa Barbara, California : Praeger,2017. ISBN 9781440854835 (p.213)

- "E.C. Segar of Thimble Theatre (starring Popeye the Sailor) was unquestionably a powerful influence in shaping Barks's comedy.." Barrier, Michael. Funnybooks : The Improbable Glories of the Best American Comic Books.University of California Press, Oakland, California, 2015. ISBN 9780520960022 (p.146).

- "1936 Popeye strip by E.C. Segar, an influence on Crumb and other underground cartoonists". Dean, Michael, and Groth, Gary.The Comics Journal Library: Zap — The Interviews. Seattle (Wa) : Fantagraphics Books, 2015. ISBN 9781606997888 (p.25)

- Mint Condition: How Baseball Cards Became an American Obsession, pp. 125–126, Dave Jamieson, 2010, Atlantic Monthly Press, imprint of Grove/Atlantic Inc., New York, NY, ISBN 978-0-8021-1939-1

- "NCS Awards". Reuben.org. September 22, 1965. Retrieved May 12, 2011.

- Young, Frank M. "Review: Thimble Theatre & The Pre-Popeye Comics of E.C. Segar" The Comics Journal, November 30, 2018. Retrieved March 2, 2022.

- "City of Chester, Illinois .::. Home of Popeye – Segar Park". Chesterill.com. Retrieved May 12, 2011.

- "City of Chester, Illinois: Popeye Character Trail". Chesterill.com. Retrieved August 21, 2013.

- "City of Chester, Illinois .::. Home of Popeye – Character Trail Page". Chesterill.com. Retrieved May 12, 2011.

Works cited

- Grandinetti, Fred (2004). Popeye: An Illustrated Cultural History. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-1605-9. Retrieved June 24, 2012.

Further reading

- Blackbeard, Bill. Marschall, Richard (ed.). "E. C. Segar's Knockabouts of 1925 (and low blows before and after): The Unknown Thimble Theatre Period". Nemo. Fantagraphics Books (3): 6–25.

External links

- Official site for Popeye & Friends Character Trail

- "E.C. Segar" by Ed Black

- "The Rime of the Ancient Mariner" by Zak Sally Minneapolis City Pages

- Lambiek Comiclopedia article about E.C. Segar

- E.C. Segar Gallery

- "Popeye's Pop EC Segar"

- E.C. Segar's 115th Birthday Doodle in Google Logo Museum

- E. C. Segar at Find a Grave