Lake Elsinore, California

Lake Elsinore is a city in western Riverside County, California, United States. Established as a city in 1888, it is on the shore of Lake Elsinore, a natural freshwater lake about 3,000 acres (1,200 ha) in size. The city has grown from a small resort town in the late 19th and early 20th centuries to a suburban city with over 70,000 residents.

City of Lake Elsinore | |

|---|---|

View of Lake Elsinore | |

| |

| Motto: "Dream Extreme"[1] | |

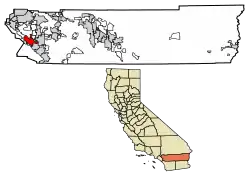

Location of Lake Elsinore in Riverside County, California | |

City of Lake Elsinore Location in California  City of Lake Elsinore City of Lake Elsinore (the United States) | |

| Coordinates: 33°40′53″N 117°20′43″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | California |

| County | |

| Incorporated | April 9, 1888[2] |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council-Manager |

| • Mayor | Timothy J. Sheridan |

| • Mayor Pro Tem | Natasha Johnson |

| • City Council | Bob Magee Steve Manos Brian Tisdale |

| • Treasurer | Allen P. Baldwin[3] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 43.51 sq mi (112.70 km2) |

| • Land | 38.24 sq mi (99.03 km2) |

| • Water | 5.28 sq mi (13.67 km2) 13.14% |

| Elevation | 1,296 ft (395 m) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 70,265 |

| • Estimate (2022)[7] | 71,898 |

| • Density | 1,880.18/sq mi (726.02/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−8 (PST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−7 (PDT) |

| ZIP Codes | 92530–92532 |

| Area code | 951 |

| FIPS code | 06-39486 |

| GNIS feature IDs | 1652704, 2411601 |

| Website | www |

History

Native Americans have long lived in the Elsinore Valley. The Luiseño people were the earliest known inhabitants. Their pictographs can be found on rocks on the Santa Ana Mountains and in Temescal Valley, and artifacts have been found all around Lake Elsinore and in the local canyons and hills.

Overlooked by the expedition of Juan Bautista de Anza, the largest natural lake in Southern California was first seen by the Spanish Franciscan padre Juan Santiago, exploring eastward from the Mission San Juan Capistrano in 1797. In 1810, the water level of the Laguna Grande was first described by a traveler as being little more than a swamp about a mile long.[8] Later in the early 19th century, the lake grew larger, providing a spot to camp and water their animals for Mexican rancheros, American trappers, the expedition of John C. Frémont, and the immigrants during the California Gold Rush as they traveled along the southern shore of the lake on what later became the Southern Emigrant Trail and the route of the Butterfield Overland Mail.

On January 7, 1844, Julian Manriquez acquired the land grant to Rancho La Laguna, a tract of almost 20,000 acres (8,100 ha) which included the lake and an adobe being built near the lake on its south shore at its western corner that was described by Benjamin Ignatius Hayes, who stayed there overnight January 27, 1850.[9]

In 1851, Abel Stearns acquired the rancho and sold it in 1858 to Augustin Machado. Augustin Machado built a seven-room adobe ranch house and an outbuilding on the southwest side of the lake. Soon after, Rancho La Laguna became a regular stop on the Butterfield Overland Mail route between Temecula 20 mi (32 km) to the southeast and the Temescal station 10 mi (16 km) to the northwest. The old Manriquez adobe was used as the station house. Over the years, a framed addition and a second story were added, and it was used as a post office for the small settlement of Willard from 1898 until September 30, 1902. The building stood until it was razed in 1964, at what is now 32912 Macy Street. Today, three palm trees still grow in front of the site along Macy Street in front of the property.[10][11]

As a result of the Great Flood of 1862, the level of the lake was very high, so the Union Army created a post at the lake to graze and water their horses. In the great 1862–65 drought, most of the cattle in Southern California died and the lake level fell, especially during 1866 and 1867, when practically no rain fell. However, the lake was full again in 1872, when it overflowed down its outlet through Temescal Canyon.[12]

While most of the old Californio families lost their ranchos during the great drought, the La Laguna Rancho remained in the hands of the Machado family until 1873, when most of it was sold to Englishman Charles A. Sumner. Juan Machado retained 500 acres (200 ha) on the northwest corner of the lake, where his adobe still stands near the lake at 15410 Grand Avenue.

After 1872, the lake again evaporated to a very low level, but the great rains in the winter of 1883–84 filled it to overflowing in three weeks. Descriptions of the lake at this time say that large willow trees surrounding the former low-water shore line stood 20 ft (6.1 m) or more below the high-water level and were of such size that they must have been 30 or more years old. This indicated the high water of the 1860s and 1870s must have been of a very short duration.[13]

On October 5, 1883, Franklin H. Heald and his partners Donald Graham and William Collier bought the remaining rancho, intending to start a new town. In 1884, the California Southern Railroad built a line from Colton through the Cañon de Rio San Jacinto (now Railroad Canyon) to link with San Diego, and a rail station La Laguna appeared near the corner of what is now Mission Trail and Diamond Drive. On April 9, 1888, Elsinore became the 73rd city to be incorporated in California, just 38 years after California became a state. Originally, Elsinore was in San Diego County, but the city became part of Riverside County upon its creation in 1893. It was named Elsinore after the Danish city, Helsingør, which is featured in William Shakespeare's play Hamlet. In fact, Helsingør is now a sister city of Lake Elsinore, California. Another source maintains Elsinore is a corruption of "el señor", Spanish for "the gentleman", because the city site had been owned by a don.[14]

The rainfall until 1893 was greater than normal, and the lake remained high and overflowed naturally on three or four occasions during that time. The lake water was purchased by the Temescal Water Company for the irrigation of land in Corona. Its outlet channel was deepened, permitting gravity flow down the natural channel of Temescal Canyon to Corona for a year or more after the water level sank below the natural elevation of its outlet. As the lake surface continued to recede, a pumping plant was installed and pumping was continued a few seasons, but the concentration of salts in the lake, due to the evaporation and lack of rainfall, soon made the water unfit for irrigation and the project was abandoned by the company.[13]

From the beginning, the mineral springs near the lake attracted visitors seeking therapeutic treatments. In 1887, the Crescent Bath House, now known as "The Chimes", was built; it still stands in historic downtown and is a registered national historic site. By 1888, the economy was supported by coal and clay mining at what became the town of Terra Cotta, gold mining in the Pinacate Mining District, ranching, and the agriculture of fruit and nuts. After 1893, the lake's water level sank almost continuously for nearly 10 years, with a slight rise every winter. Heavier precipitation, beginning in 1903, gradually filled the lake to about half the depth above its minimum level since 1883. Then, in January 1916, a flood rapidly raised the level to overflowing.

Lake Elsinore was a popular destination in the first half of the 1900s for celebrities to escape the urban Hollywood scene. Many of their homes still stand on the hills surrounding the lake, including Aimee's Castle, a unique Moorish-style house built by Aimee Semple McPherson. Also, actor Bela Lugosi, known for his lead role in Universal Pictures' film, Dracula, built a home that still exists in the city's Country Club Heights district.

The Riverside Daily Press published this description in December 1919:

- The city of Elsinore nestles snuggly on the west side of the lake, while it is backed by stately foothills through which traverses one of the famous state highways leading to Riverside and Los Angeles to the west and to San Diego to the southwest.

- Its elevation of 1300 feet makes its climate delightful, especially in the cold months of winter. It has school facilities for a city twice its population, including a modern high school, grammar school and kindergarten.

- It is one of few cities of its size in the state that has its own sewer system. It has an ornamental lighting system and five blocks of the city’s business section are paved from curb to curb with concrete. There are yet two and one-half miles of this kind of street to be laid on the streets entering the city from the south and west, connecting up with the inland highway system to San Diego and Riverside and Los Angeles.

- Elsinore has three churches, the Methodist Episcopal, Presbyterian, Roman Catholic, while the Episcopal and Christian Scientists hold regular services in leased property.

- The health record of the city is perhaps one of its greatest features. During the recent epidemic of Spanish influenza, which swept the country and the world, Elsinore escaped with but a few cases. Only three deaths were attributed to the disease.[15]

The lake also hosted teams for Olympic training and high-speed boat racing in the 1920s. The lake went dry in the mid-1930s, but refilled by 1938.[13]

During World War II, the lake was used to test seaplanes, and a Douglas Aircraft plant making wing assemblies for Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress bombers was located in the city.[16] The lake ran dry during most of the 1950s and was refilled in the early 1960s.

Despite its relatively small African American population, it has the distinction of electing the first black city councilman in California, Thomas R. Yarborough, in 1948.[17][18][19] Yarborough went on to become one of three African American mayors elected in California in 1966.[19]

In 1972, citizens of the city voted to rename it Lake Elsinore.[20] More than a week of heavy rains in 1980 flooded the lake, destroying surrounding homes and businesses. Since then, a multimillion-dollar project has been put into place to maintain the water supply at a consistent level, allowing for homes to be built close to the lake. Overflow water in the Lake spills out via Alberhill Creek, a tributary of Temescal Creek. In 2007, an aeration system was added to help with the lake's ecosystem.

Rapid population growth in the mid-2000s altered the appearance and image of Lake Elsinore from a small lakeside town of 3,800 people in 1976 to a bedroom community of upper middle-class professionals. The city was ranked as the 12th fastest growing city in California between 2000 and 2008.[21] Now, over 70,000 residents as of the 2020 census live there, and formerly open hillsides have been converted into housing tracts.[22]

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 41.7 sq mi (108.0 km2) of which 36.2 sq mi (93.8 km2) of it is land and 5.5 sq mi (14.2 km2), or 13.14%, is covered by water.

Lake Elsinore, originally Laguna Grande, is the largest natural freshwater lake in Southern California and is situated at the lowest point within the 750-square-mile (1,900 km2) San Jacinto River watershed at the terminus of the San Jacinto River, where its headwaters are found on the western slopes of San Jacinto Peak with its North Fork, and Lake Hemet with its South Fork. Lake levels are healthy at 1,244 feet (379 m) above sea level with a volume of 30,000 acre⋅ft (37 Gl)[23] that often fluctuate, although much has been done recently to prevent the lake from drying up, flooding, or becoming stagnant. At 1,255 feet (383 m), the lake would spill into the outflow channel on its northeastern shore, known properly as Temescal Wash, flowing northwest along I-15, which feeds Temescal Creek, which dumps into the Santa Ana River just northwest of the City of Corona. It then flows to Orange County, out to the Pacific Ocean just south of Huntington State Beach.

Lake Elsinore is bordered by the Elsinore Mountains to the west, which are a part of the larger Santa Ana Mountain Range, and receive a few inches of snowfall a few days each year. Included in the Santa Ana Mountains is the Cleveland National Forest and the community of El Cariso. Lake Elsinore is northwest of Wildomar and the northern portion is part of the Temescal Canyon. To the east of the lake are the much older and more eroded slopes of the Temescal Mountains.

Districts

Lake Elsinore is a city which encompasses a large geographical area. To better distinguish the wide range of neighborhoods, the city is organized into 11 districts. Each district beholds its own unique geography, culture, age, and history which together make Lake Elsinore a very diverse and culturally rich city. They are the Alberhill, Ballpark, Business, Country Club Heights, East Lake, Historic, Lake Edge, Lake Elsinore Hills, Lake View, North Peak, and Riverview Districts.[24]

Alberhill

The Alberhill District is characterized by rolling terrain, vacant land, and the newly constructed Alberhill Ranch neighborhood. Much of the topography in the central areas, east and west of Lake Street, has been substantially altered as a result of the Alberhill District's long history of extractive/mining activities. Mining operations in the Alberhill District began at Terra Cotta roughly the same time the region's first railroad, the California Southern Railroad, was completed in the 1880s. A spur of the railroad originally built to Terra Cotta was extended into the central portion of the Alberhill District. The Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad built a line up from Corona through Alberhill to Elsinore after the line through Railroad Canyon was washed out in the 1920s. These events helped shape the growth of the District. Mining operations for coal and especially clay have continued to exist since the late 19th century, and occupy a significant portion of the Alberhill District. Through the years, Pacific Clay Products Company has purchased the local mines and has become the sole operating clay mine in the region.[25]

Ballpark

The Ballpark District takes its name from the Lake Elsinore Diamond Stadium, a first-class minor league baseball stadium constructed in 1994. It is home to the Lake Elsinore Storm professional baseball team, an affiliate of the San Diego Padres. The area was once the site of the first train depot in Lake Elsinore, but no train tracks or structures from that era remain.[26]

Business

The developed area within the Business District, in Warm Springs Valley, is relatively new and has the strongest concentration of industrial and commercial uses within the city. In addition, it hosts several big-box retailers, the Lake Elsinore Outlets, the lake's outlet channel, Temescal Creek, and marshlands. It is bordered by Country Club Heights to the west and Interstate 15 to the east, with a small portion extending to the east side of I-15. Sections of the Atchison, Topeka, & Santa Fe Railroads that passed through the Business District during the 1800s have been removed. In addition, a historic ranching and homesteading site with previous ranching and homesteading activities is located nearby the route where the railroad once existed.[27]

Country Club Heights

The Country Club Heights District is distinctly marked by the steep hillsides of the Clevelin Hills, views of the lake and the City, and is a key part of Lake Elsinore's history. The issues mentioned above have presented development constraints for Country Club Heights since its historic beginnings dating back to 1912. The area was the target of an elaborate land scheme promoted in Los Angeles. The Mutual Benefit and Loan Society of Los Angeles acquired two pieces of dry, "hill-land" within a few miles north of "town-land" that the Press claimed was not worth ten cents an acre. The Mutual Benefit and Loan Society offered to give a 25-by-100-foot (7.6 m × 30.5 m) lot to anyone who asked; however, the person receiving the lot had to pay ten dollars for a membership in the Club, and one dollar per month dues for five years. In 1924, the Clevelin Realty Corporation, headed by Abe Corlin (President) and Henry Schultz (Treasurer-Secretary), began selling additional lots in Country Club Heights and launched a real estate sales promotion in the area. The Clevelin Hills took their name from this company.

Noteworthy sites in the Country Club Heights District include: the Schultz Mansion (now Bredlau Castle) and the Corlin Mansion, both built by the Corporation on the Clevelin Hills in 1926 for Henry Schultz and Abe Corlin, respectively, who had originated the Clevelin Realty development. The Bredlau castle is over 9,000 sq ft (840 m2), and includes a hidden room with a sliding bookcase door that was used during Prohibition. These stately homes overlooking the lake were the site for many social gatherings. The winding roads of Country Club Heights are adorned with historic Marbelite lampposts, designed by Henry Barkschat.[28] In 2007, the City of Lake Elsinore restored the historic lampposts along Lakeshore Drive.[29]

In October 1928, Aimee Semple McPherson, a renowned evangelist, commissioned Architect Edwin Dickman to design for her a palatial home in Country Club Heights, which has since won fame as "Aimee's Castle".[30] This is said to be a house born of Hollywood, inspired by Moorish architectural design. This home served as the evangelist's part-time home until 1939, when it passed to new ownership. After changing hands many times, in 2005, International Church of the Foursquare Gospel, the modern incarnation of McPherson's Foursquare Gospel, purchased and restored the property after years of neglect.[31][32]

The Clevelin Country Club (later known as the Lake Elsinore Country Club, The Spa Club and the Casino Del Elsinore) was built to be the main attraction of the Country Club Heights subdivision.[33] Prominent members of the club included Mrs. Wallace Reid, Marie Prevost, Reginald Denny, Jack Dempsey, Bert Lytell, Damon Runyon and Joe Stecher, for whom the streets are so named[34] This Spanish-Mediterranean Moorish accented architectural masterpiece had over 20,000 square feet of floor space and included a ballroom, banquet hall, sleeping quarters, and a tunnel system to hidden rooms. The Country Club closed during the depression, but reopened in 1951. It has closed again before 1981, at which point restoration work was being undertaken, but by 1990 the property was vacant and derelict.[33] The Country Club succumbed to arson in 2001.[35]

East Lake

The East Lake District is partially developed and contains the newly constructed Summerly neighborhood. It is a generally flat area that does not contain any registered historic structures. However, portions of the East Lake District were used during prehistoric times by Native American Indians as flaking and grinding stations. In addition, a historic ranching and homesteading site is located just outside the East Lake District along the border with Lakeland Village to the southwest. More recently, the East Lake District has also been home to popular motocross, skydiving, glider plane, and hang gliding activities. Throughout the city's history, Lake Elsinore has alternated between severe floods and droughts. Most of the East Lake District lies within a 100-year floodplain adjacent to and southeast of the lake. As a result, the district has been significantly affected during wet seasons and high water levels in the lake. Major floods occurred in 1884 and in 1916. In 1969, 7 in (180 mm) of rain fell in 11 days and severely flooded the lake's shores. The East Lake District's proximity to the lake and flood storage is a key consideration in all planned development and several projects have been implemented to prevent the lake from flooding again.[36]

Historic District

The Historic District has been the focal point of the city since its incorporation in 1888.

In 1925, W.R. Covington and Associates of Santa Monica purchased 650 ft (200 m) of lake frontage and three blocks of slightly improved land across Poe Street from Warm Springs Park. A clubhouse, swimming pool, and other facilities projected to cost $200,000 (or $3.3 million today) were built on this property. No records have been found to provide the date when a fire destroyed the clubhouse, but remnants of the burned structure and surrounding trees examined in 1942 indicate the fire must have occurred soon after the building was constructed.[37] The Covington resort was built in the Town of Elsinore.

Today, several unregistered historic buildings exist, including the Crescent Bath House, also known as "The Chimes"; The Chamber of Commerce (Santa Fe Train Station); The Cultural Center (The Methodist Church); Armory Hall; The Ambassador Hotel (Elsinore Consolidated Bank); Jean Hayman House; and Elsinore City Park[38] The neighborhoods in this area are the oldest in the city, and its commercial strip along Main Street is considered to be downtown.[39]

Lake Edge District

The Lake Edge District area has had a long and eventful history, with the lake as a focal point for the Native Americans, Europeans, Mexicans, early founders of the City, and the multitude of visitors and locals who continue to come to its shores for entertainment and recreation. Many developments occurred along or within proximity of the lake's edge during the second half of the 19th and the first half of the 20th centuries.

The Lake Edge District encompasses the ruins of the city's oldest standing structure, the Machado Adobe House, Rancho La Laguna[40] This site was the location of the Laguna Grande Butterfield Stage Station. This structure succumbed to arson in 2017.[41]

A structure of historical interest is Meyer & Holler designed Southern California Athletic and Country Club, former Elsinore Naval Military Academy building, located along Grand Avenue near the intersection of Ortega Highway.[42]

A newly constructed campground, marina, and boat launch is located on the northwest side of the lake.

Lake Elsinore Hills

The Lake Elsinore Hills District encompasses a large and varied terrain including broad plains, rolling hills, steep slopes, sensitive habitats, and watercourses, with elevations ranging from 1,300 to 2,170 feet (400 to 660 m) above the sea level. Many areas of the Lake Elsinore Hills District are not readily accessible or able to be developed, so have remained vacant. Two large bodies of water located within close proximity of the Lake Elsinore Hills District are the City's lake to the southwest and Canyon Lake to the east, which is located within the city of Canyon Lake. Some of the higher elevations offer panoramic views of the City's lake and the Santa Ana Mountains. The neighborhoods in this district include Tuscany Hills, Canyon Hills, and Rosetta Canyon.[43]

Lake View

The northwestern areas of the Lake View District offer beautiful views of the lake and the neighboring mountains, and are characterized by high elevations, steep slopes, and a series of canyons. The remaining areas of the Lake View District are relatively flat in the lower elevations. Historically, the northern portion of the Lake View District has remained mostly undeveloped, with the exception of the La Laguna Estates neighborhood above McVicker Canyon Park. Similar to the areas further north, the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad and abundant mining opportunities extant in the late 19th century brought both residents and visitors to the area. Historic ranching and homesteading, including Torn Ranch, were generally located to the northwest of Machado Street, which was an important roadway lined with beautiful deodar trees. Most of the lower-lying areas of the Lake View District to the north have been recently developed and primarily include single-family homes. Other neighborhoods in this area include Northshore and Lake Terrace, which were both formerly orange groves. Another area in this district at the intersection of Riverside and Lakeshore Drives has long been to referred to as "Four Corners" by local residents.[44]

Riverview

The Riverview District is a combination of steep terrain and flat areas nestled between a knoll with steep slopes, a major watercourse, and the lake. Higher elevations and steep slopes are located in the northwest areas of the Riverview District, which function as a physical border with most of the adjacent Historic District. The San Jacinto River floodway, located within the Riverview District along the eastern and southern areas, is the city's major watercourse. The river flows southwest from Canyon Lake through the Lake Elsinore Hills District and the Riverview District, then ultimately empties into the lake.[45]

Climate

Lake Elsinore has a mild semi-arid climate (Köppen climate classification BSk/BSh), with hot, almost rainless summers and mild, wetter winters. While too dry for this classification, its thermal regime and precipitation distribution resembles that of a hot-summer Mediterranean climate (Köppen Csa), which is present in many surrounding areas.[46] On average, the hottest month is July, and the coolest month is December. The highest recorded temperature was 118 °F (47.8 °C), first recorded on August 12, 1933, and the lowest recorded temperature was 10 °F (−12.2 °C) on December 30, 1974. The maximum average precipitation occurs in February, and the minimum average precipitation in June, although less than half of all Junes, Julies, Augusts, and Septembers record any precipitation whatsoever. The greatest amount of precipitation ever received in one day was 5.28 inches (134 mm), on February 15, 1927.[47]

| Climate data for Lake Elsinore, California (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1897–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 91 (33) |

95 (35) |

103 (39) |

109 (43) |

109 (43) |

114 (46) |

117 (47) |

118 (48) |

117 (47) |

110 (43) |

98 (37) |

90 (32) |

118 (48) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 78.4 (25.8) |

82.2 (27.9) |

87.5 (30.8) |

93.8 (34.3) |

98.5 (36.9) |

103.9 (39.9) |

107.8 (42.1) |

108.3 (42.4) |

105.3 (40.7) |

98.5 (36.9) |

88.4 (31.3) |

78.8 (26.0) |

110.9 (43.8) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 65.7 (18.7) |

67.1 (19.5) |

71.5 (21.9) |

76.5 (24.7) |

82.0 (27.8) |

90.2 (32.3) |

96.5 (35.8) |

97.8 (36.6) |

93.2 (34.0) |

83.1 (28.4) |

73.2 (22.9) |

65.0 (18.3) |

80.2 (26.8) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 53.8 (12.1) |

54.9 (12.7) |

58.7 (14.8) |

62.6 (17.0) |

67.9 (19.9) |

74.3 (23.5) |

80.3 (26.8) |

81.3 (27.4) |

77.2 (25.1) |

68.5 (20.3) |

59.6 (15.3) |

52.6 (11.4) |

66.0 (18.9) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 41.9 (5.5) |

42.7 (5.9) |

45.8 (7.7) |

48.7 (9.3) |

53.8 (12.1) |

58.3 (14.6) |

64.1 (17.8) |

64.8 (18.2) |

61.2 (16.2) |

53.9 (12.2) |

45.9 (7.7) |

40.3 (4.6) |

51.8 (11.0) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 31.0 (−0.6) |

32.8 (0.4) |

35.3 (1.8) |

38.8 (3.8) |

44.8 (7.1) |

50.3 (10.2) |

54.8 (12.7) |

56.2 (13.4) |

51.8 (11.0) |

44.4 (6.9) |

35.7 (2.1) |

29.9 (−1.2) |

27.8 (−2.3) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 15 (−9) |

19 (−7) |

24 (−4) |

24 (−4) |

31 (−1) |

35 (2) |

41 (5) |

40 (4) |

35 (2) |

25 (−4) |

20 (−7) |

17 (−8) |

15 (−9) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 2.97 (75) |

2.85 (72) |

1.49 (38) |

0.54 (14) |

0.21 (5.3) |

0.07 (1.8) |

0.18 (4.6) |

0.06 (1.5) |

0.17 (4.3) |

0.51 (13) |

0.59 (15) |

2.01 (51) |

11.65 (296) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.2 (0.51) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.2 (0.51) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 5.6 | 5.8 | 4.7 | 2.5 | 1.4 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 2.0 | 2.8 | 5.3 | 31.9 |

| Average snowy days | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 |

| Source 1: NOAA[48] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: National Weather Service[49] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1900 | 279 | — | |

| 1910 | 488 | 74.9% | |

| 1920 | 633 | 29.7% | |

| 1930 | 1,350 | 113.3% | |

| 1940 | 1,552 | 15.0% | |

| 1950 | 2,068 | 33.2% | |

| 1960 | 2,432 | 17.6% | |

| 1970 | 3,530 | 45.1% | |

| 1980 | 5,982 | 69.5% | |

| 1990 | 18,285 | 205.7% | |

| 2000 | 28,928 | 58.2% | |

| 2010 | 51,821 | 79.1% | |

| 2020 | 70,265 | 35.6% | |

| 2022 (est.) | 71,898 | [7] | 2.3% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[50] | |||

| Demographic profile | 2020 | 2010 | 2000 | 1990 | 1980 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | 39.5% | 60.0% | 65.6% | 76.9% | 80.4% |

| —Non-Hispanic (NH) | 30.2% | 37.8% | 51.4% | 67.7% | 72.4% |

| Black or African American (NH) | 6.4% | 4.8% | 5.0% | 3.8% | 8.1% |

| Hispanic or Latino (of any race) | 51.0% | 48.4% | 38.0% | 25.8% | 18.0% |

| Asian (NH) | 7.0% | 5.6% | 2.0% | 1.7% | - |

| American Indian (NH) | 0.4% | 0.4% | 0.7% | 0.9% | - |

| Other (NH) | 5.0% | 3.0% | 2.9% | 0.1% | 1.6% |

2010

The 2010 United States Census[51] reported Lake Elsinore to have a population of 51,821. The population density was 1,243.1 inhabitants per square mile (480.0/km2). The racial makeup of Lake Elsinore was 31,067 (60.0%) White (37.8% Non-Hispanic White),[52] 2,738 (5.3%) African American, 483 (0.9%) Native American, 2,996 (5.8%) Asian, 174 (0.3%) Pacific Islander, 11,174 (21.6%) from other races, and 3,189 (6.2%) from two or more races. Hispanics or Latinos of any race were 25,073 persons (48.4%).

The census reported 51,389 people (99.2% of the population) lived in households, 224 (0.4%) lived in non-institutionalized group quarters, and 208 (0.4%) were institutionalized.

Of the 14,788 households, 8,026 (54.3%) had children under the age of 18 living in them, 8,735 (59.1%) were married couples living together, and 2,071 (14.0%) had a female householder with no husband present, 1,155 (7.8%) had a male householder with no wife present. There were 1,165 (7.9%) unmarried opposite-sex partnerships, and 143 (1.0%) same-sex partnerships. Some 1,952 households (13.2%) were made up of individuals, and 521 (3.5%) had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 3.48. There were 11,961 families (80.9% of all households); the average family size was 3.79.

The population was distributed as 16,990 people (32.8%) under the age of 18, 5,261 people (10.2%) aged 18 to 24, 15,731 people (30.4%) aged 25 to 44, 10,874 people (21.0%) aged 45 to 64, and 2,965 people (5.7%) who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 29.8 years. For every 100 females, there were 100.4 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 98.5 males.

The 16,253 housing units averaged a density of 389.9 per square mile (150.5/km2), of which 9,761 (66.0%) were owner-occupied, and 5,027 (34.0%) were occupied by renters. The homeowner vacancy rate was 4.6%; the rental vacancy rate was 6.8%. About 32,891 people (63.5% of the population) lived in owner-occupied housing units and 18,498 people (35.7%) lived in rental housing units.

According to the 2010 United States Census, Lake Elsinore had a median household income of $62,436, with 13.2% of the population living below the federal poverty line.[52]

Economy

One of the first outlet centers in California was established in northwestern Lake Elsinore in the late 1990s on Collier Avenue at Nichols Road, just off Interstate 15. The center, known as the Outlets at Lake Elsinore, has a wide variety of retailers, encompassing clothing and shoe stores, eateries, bookstores, perfumeries, home and garden boutiques, and electronics stores.[53]

Pacific Clay is among the companies based in Lake Elsinore.

Top employers

According to the City's 2022 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report,[54] the top employers in the city are:

| # | Employer | No. of employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Lake Elsinore Unified School District | 2,541 |

| 2 | M & M Framing | 516 |

| 3 | Stater Bros. Markets | 347 |

| 4 | Costco Wholesale | 312 |

| 5 | Walmart | 295 |

| 6 | Lake Elsinore Hotel & Casino | 240 |

| 7 | Riverside County Department of Social Services | 206 |

| 8 | EMVWD (Elsinore Valley Municipal Water District) | 163 |

| 9 | The Home Depot | 160 |

| 10 | City of Lake Elsinore | 141 |

Government

In the California State Legislature, Lake Elsinore is in the 32nd Senate District, represented by Republican Kelly Seyarto, and in the 63rd Assembly District, represented by Republican Bill Essayli.[55]

In the United States House of Representatives, Lake Elsinore is in California's 41st congressional district, represented by Republican Ken Calvert.[56]

Services

Public safety

The Riverside County Sheriff's Department serves the entire Lake Elsinore Valley (including the nearby community of Lakeland Village and the City of Wildomar) from its regional station in downtown Lake Elsinore. The city once had its own police department, but it was disbanded in 1970 for budgetary reasons.

The city of Lake Elsinore contracts for fire and paramedic services with the Riverside County Fire Department through a cooperative agreement with CAL FIRE.[57] Lake Elsinore currently has three paramedic engines and one paramedic truck company operating from its four stations.

Fire Station 10 is located downtown next to the post office, which also has two CAL FIRE engines for supplemental protection. Fire Station 85 is located at McVicker Park and Fire Station 94 is located on the east side of the city off of Railroad Canyon Road. Rosetta Canyon Fire Station 97 is located on the northeast side of the city covering the Highway 74 corridor.

Education

Public education within most of the city of Lake Elsinore and the surrounding areas is provided by the Lake Elsinore Unified School District, which serves a student population of about 21,500.[58] The school district has 15 elementary schools, five middle schools, three high schools, and three alternative schools.[59]

Lakeside, Temescal Canyon, and Elsinore are the three main high schools of the Lake Elsinore Unified School District. A very small portion of northeastern Lake Elsinore in the Canyon Hills subdivision is located in the Menifee Union School District for grades K-8, and Perris Union High School District for grades 9–12.

Additionally, three private schools are within the city of Lake Elsinore, including a K–12 preparatory academy.[60][61]

Libraries and post office

There are two libraries located in the city: the Lake Elsinore Library at 600 W. Graham Avenue and the Lakeside Library at 32593 Riverside Drive. Both library branches are owned and operated by the Riverside County Library System.[62]

The United States Postal Service operates a post office at 500 W. Graham Avenue in Lake Elsinore.

Cemetery

The Elsinore Valley Cemetery District[63] maintains a public cemetery in the city.[64] The cemetery was established in 1891 by Peter Wall.[65] The Jewish Home of Peace Cemetery, a.k.a. Mt. Sinai Memorial Park of Elsinore, is part of the cemetery.[66]

The Manker Family Cemetery is an historical cemetery located on the family property. Three known burials are from 1887–1902, with evidence of at least one other burial. The four wooden tombstones were burned in a fire.

Transportation

Roads and highways

Lake Elsinore is served by Interstate 15, which connects the city to points south such as Murrieta, Temecula and San Diego, and to points north such as Corona, Ontario and Las Vegas. Construction is expected to begin around 2025 on a set of toll lanes in the median of Interstate 15 that would extend south from Corona to the northern part of Lake Elsinore.[67][68] Lake Elsinore is also served by State Route 74, which connects the city with Orange County to the west as well as points east including Perris, the San Jacinto Valley, and the Coachella Valley. Long-range plans include upgrading State Route 74 and placing it on a new, more direct expressway alignment known as the Ethanac Expressway.[69]

In addition to highways, many of Lake Elsinore's primary streets connect the city with other cities nearby. Grand Avenue and Mission Trail both connect Lake Elsinore with the neighboring city of Wildomar, and to the east Railroad Canyon Road connects Lake Elsinore with the city of Canyon Lake as well as the city of Menifee (where it becomes Newport Road). Temescal Canyon Road continues from the northwestern part of the city and passes through the unincorporated community of Temescal Valley before reaching the city of Corona.

Public transportation

Riverside Transit Agency has several local and express bus routes serving the city of Lake Elsinore, including Routes 8, 9, 40, 205, and 206.[70]

Sports

Lake Elsinore Diamond

Lake Elsinore Diamond serves as a site for the Single A baseball team Lake Elsinore Storm, which is a farm team for the San Diego Padres, and was formerly a farm team for the Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim. Also, it held now-disbanded semipro football teams: The Riverside-Elsinore Dolphins of the Western States Football League was active in 1996–98. The stadium hosted the Banning-Elsinore Eagles of the California Football Association, a minor American football league. It used to host the Elsinore-Murrieta Bandits, a semipro soccer team in the 2010s. In 2020, neither football or soccer is played at "the Diamond", but special events, such as concerts with stars such as Willie Nelson and ZZ Top, are held there.

Cross monument lawsuit

In 2012, the city council voted to approve $50,000 for a memorial to veterans that would be placed in front of the stadium. The design of the memorial included a soldier kneeling in front of a Christian cross. After repeated warnings to the city council from the city attorney and others that endorsing religion using public funds is unconstitutional, the city council unanimously voted to include a Star of David, as well as more Christian crosses. In 2013, the American Humanist Association filed suit to prevent the building of the monument.[71][72] The Pacific Justice Institute provided free legal representation to the city in the suit.[73] A federal court issued a preliminary injunction in July 2013 halting the project, and in February 2014 ruled that the design "violates both the U.S. Constitution's Establishment Clause and the Establishment and No Preference Clauses of the California Constitution."[73][74] The City Council declined to appeal the decision, and agreed to pay plaintiffs $200,000 in attorneys' fees and to develop a revised design for the memorial.[75] At a meeting in June 2014, the council approved an amended design.[76] The 3,600-pound (1,600 kg) memorial, absent of religious symbols, was finally installed and commemorated in November 2014.[77][78]

Elsinore Grand Prix

The Elsinore Grand Prix is a dirt-bike race that takes place in and around the Lake Elsinore area. The annual race is usually held in mid-November. The popularity of the event hit its apex in the late 1960s and early 1970s, drawing the likes of dirt-bike greats such as Malcolm Smith and Steve McQueen, to name a few. The race has always been set as an "open" format, meaning anyone can ride; usually only about 200 or so take this event seriously, whereas the rest use it as an opportunity to have fun. In 1971, the documentary movie On Any Sunday by Bruce Brown included scenes from the grand prix.[79]

In the mid-1970s the Elsinore Grand Prix hit a snag, none of the big riders were participating, and the event was drawing the wrong crowd, mostly violent motorcycle gangs. The race was cancelled indefinitely soon afterwards. In 1996, several dirt-bike riders, with a hint of nostalgia, decided to lobby the city of Lake Elsinore to revive the Grand Prix. Promising that the violent motorcycle gang crowd drawn to the Grand Prix in the 1970s had gone and that dirt-bike motorcycle riding was more of a family event, the city allowed the event to resume on a provisional basis.

In 1973, Honda named its CR250M Elsinore—the first motorcycle designed by Honda for the dirt rather than a modified street bike—after the Elsinore GP race venue.[80]

Lake Elsinore is also a popular destination for motorcyclists riding east from San Juan Capistrano along the 33-mile (53 km) long Ortega Highway.[79]

Skateparks

Lake Elsinore offers two skateparks in both north and south of the areas. McVicker Canyon Park was the first city-owned skatepark to be built in Lake Elsinore located between Grand Avenue and McVicker Canyon Park Road. Serenity Park was built in June 2015 and is located on Palomar Road. The city hired Spohn Ranch Skateparks, an internationally renowned firm in Los Angeles, for about $400,000 to design and build the state-of-the-art 8,500-square-foot, open-air plaza that features a peanut-shaped bowl, hip ramps, step-up and quarter-pipes. It is the second city-owned skatepark.[81]

Notable people

- Eva Scott Fenyes (artist)

- Kodi Lee, America's Got Talent Season 14 winner

- Jon Serl, painter[82]

- Aaron Wise, Professional golfer on the PGA Tour.

- Thomas Yarborough, former mayor and city council member

References

- "City of Lake Elsinore, California Website". City of Lake Elsinore, California Website. Retrieved September 14, 2012.

- "California Cities by Incorporation Date". California Association of Local Agency Formation Commissions. Archived from the original (Word) on November 3, 2014. Retrieved August 25, 2014.

- "City Treasurer". City of Lake Elsinore. Archived from the original on August 10, 2014. Retrieved September 22, 2014.

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- "Lake Elsinore". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved November 3, 2014.

- "Lake Elsinore city, California". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved November 13, 2021.

- "City and Town Population Totals: 2020-2022". United States Census Bureau. United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 13, 2023.

- "Water-supply Paper". U.S. Government Printing Office. March 13, 1919. Retrieved March 13, 2019 – via Google Books.

- "American Memory from the Library of Congress". memory.loc.gov. Retrieved March 13, 2019.

- Historic Spots in California, Third Edition. Stanford University Press. 1966. ISBN 9780804740203. Retrieved March 13, 2019 – via Google Books.

- "Historical Topographic Map, Elsinore, Edition Date: 1901, Scale 1/125000". Archived from the original on December 19, 2002. Retrieved June 19, 2011.

- Water-supply paper, Volumes 425–429 By Geological Survey (U.S.), History of Elsinore Lake, p. 255]

- Water-supply paper, Volumes 425–429 By Geological Survey (U.S.), History of Elsinore Lake, p. 255

- Gannett, Henry (1905). The Origin of Certain Place Names in the United States. Govt. Print. Off. p. 118.

- Staff, “Elsinore Valley And Its Ranching Possibilities,” Riverside Daily Press, Riverside, California, Saturday evening 13 December 1919, Volume XXXIV, Number 269, part 2, page 1.

- Tom Hudson, Lake Elsinore Valley, its story 1776–1977, 2nd Ed., Published by author, 1988. ISBN 0-931700-01-9

- Forrey, Kathy (August 1, 1990). "More than 200 pay homage to Yarborough". Lake Elsinore Valley Sun-Tribune. Retrieved July 22, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- Jefferson, Alison Rose (2022). Living the California Dream: African American Leisure Sites During the Jim Crow Era. University of Nebraska Press. pp. 129–131. ISBN 9781496229069.

- "Race Barriers Drop: State cities pick mayors". Times-Advocate. United Press International. April 20, 1966. p. 8. Retrieved July 22, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- Lake Elsinore Historical Society, Lake Elsinore, Arcadia Publishing, 2008, p. 10 ISBN 978-0738555881 OCLC 176900939

- "Pacific Standard Magazine". Retrieved April 27, 2012.

- "Lake Elsinore city, California". United States Census Bureau. United States Census Bureau. Retrieved April 1, 2022.

- "State Water Resources Control Board" (DOC). Swrcb.ca.gov. Retrieved November 24, 2021.

- City of Lake Elsinore General Plan Archived April 15, 2012, at the Wayback Machine Revised 2011-12-13

- City of Lake Elsinore General Plan Archived September 13, 2013, at the Wayback Machine Adopted 2011-12-13

- City of Lake Elsinore General Plan Archived September 13, 2013, at the Wayback Machine Adopted 2011-12-13

- City of Lake Elsinore General Plan Archived September 13, 2013, at the Wayback Machine Adopted 2011-12-13

- Lake Elsinore. 2008. ISBN 9780738555881.

- "Lake Elsinore lampposts restored". San Diego Union-Tribune. May 4, 2007. Retrieved November 24, 2021.

- "LAKE ELSINORE: "Aimee's Castle" is on the market". San Diego Union-Tribune. March 22, 2010. Retrieved November 24, 2021.

- "Home of the Week: Sister Aimee's castle in Lake Elsinore". Los Angeles Times. May 9, 2010. Retrieved November 24, 2021.

- City of Lake Elsinore General Plan Archived September 13, 2013, at the Wayback Machine Adopted 2011-12-13

- Survey of Historical Structures and Sites Lake Elsinore California. Elsinore Valley Community Development Corporation. 1991. pp. 51–52.

- New Country Club Is Rising at Elsinore, San Bernardino County Sun, Wednesday 05 May 1926, Page 11

- "Fire investigators officially list arson as cause of country club fire". San Diego Union-Tribune. February 15, 2001. Retrieved November 24, 2021.

- City of Lake Elsinore General Plan Archived September 13, 2013, at the Wayback Machine Adopted 2011-12-13

- Beach Resort, Source: May 14, 1925, Lake Elsinore Valley Press

- "DOWNTOWN MAIN STREET HISTORICAL BUILDINGS". Lake-elsinore.org. Retrieved November 24, 2021.

- City of Lake Elsinore General Plan Archived September 13, 2013, at the Wayback Machine Adopted 2011-12-13

- Rancho La Laguna

- "Another Lake Elsinore historical structure lost to fire". Pe.com. September 8, 2017. Retrieved November 24, 2021.

- City of Lake Elsinore General Plan Archived September 13, 2013, at the Wayback Machine Adopted 2011-12-13

- City of Lake Elsinore General Plan Archived September 13, 2013, at the Wayback Machine Adopted 2011-12-13

- City of Lake Elsinore General Plan Archived September 13, 2013, at the Wayback Machine Adopted 2011-12-13

- City of Lake Elsinore General Plan Archived September 13, 2013, at the Wayback Machine Adopted 2011-12-13

- Beck, H.E., Zimmermann, N. E., McVicar, T. R., Vergopolan, N., Berg, A., & Wood, E. F. Beck, Hylke E.; Zimmermann, Niklaus E.; McVicar, Tim R.; Vergopolan, Noemi; Berg, Alexis; Wood, Eric F. (2018). "Present and future Köppen-Geiger climate classification maps at 1-km resolution". Scientific Data. 5: 180214. Bibcode:2018NatSD...580214B. doi:10.1038/sdata.2018.214. PMC 6207062. PMID 30375988.

- "Lake Elsinore historic weather averages". Western Regional Climate Center. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- "U.S. Climate Normals Quick Access – Station: Elsinore, CA". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved May 24, 2023.

- "NOAA Online Weather Data – NWS San Diego". National Weather Service. Retrieved May 24, 2023.

- "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved November 13, 2021.

- "2010 Census Interactive Population Search: CA - Lake Elsinore city". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved July 12, 2014.

- "Lake Elsinore (city) QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on April 26, 2015. Retrieved April 15, 2012.

- "Outlets at Lake Elsinore". Outlets at Lake Elsinore. Retrieved March 13, 2019.

- "City of Lake Elsinore, California Comprehensive Annual Financial Report for Fiscal Year ended June 30, 2022". Retrieved January 1, 2023.

- "Statewide Database". UC Regents. Archived from the original on February 1, 2015. Retrieved December 16, 2014.

- "California's 42nd Congressional District - Representatives & District Map". Civic Impulse, LLC.

- "Service Area". rvcfire.org. Retrieved March 13, 2019.

- "Lake Elsinore Unified School District School District in Lake Elsinore, CA". Greatschools.org. Retrieved March 13, 2019.

- "Lake Elsinore Unified School District". Leusd.k12.ca.us. Retrieved March 13, 2019.

- "Lake Elsinore Schools | CA - Ratings and Map of Public and Private Schools". Localschooldirectory.com. Retrieved March 13, 2019.

- "Mountainside Ministries, Lake Elsinore, Christian Church". Go2mountainside.com. Retrieved March 13, 2019.

- "Riverside County Library System". Locations. Riverside County Library System.

- "California Association of Public Cemeteries". Capc.info. Retrieved March 13, 2019.

- "USGS Geographic Names Information System (GNIS)". Geonames.usgs.gov. Retrieved March 13, 2019.

- Shirley Brooks, "History of Elsinore Valley Cemetery", Lake Elsinore Genealogical Society access-date=September 30, 2011

- "Lake Elsinore: Riverside County". International Jewish Cemetery Project. International Association of Jewish Genealogical Societies.

- "After voters keep gas tax, plans for 15 Freeway toll lanes from Corona to Lake Elsinore move ahead". Press Enterprise. November 9, 2018. Retrieved February 10, 2020.

- "Funding Received for Extension of I-15 Express Lanes, Cajalco Road to State Route 74". Riverside County Transportation Commission. March 23, 2018. Retrieved February 10, 2020.

- "Input sought on Ethanac Expressway that would link Hemet to Lake Elsinore". Pe.com. January 23, 2018. Retrieved November 24, 2021.

- "Maps & Schedules - Riverside Transit Agency". Riversidetransit.com. Retrieved November 24, 2021.

- "Lake Elsinore: Cross will remain on veterans memorial". The Press-Enterprise. November 13, 2012.

- "Lake Elsinore: Humanist group sues over cross on planned monument". The Press-Enterprise. June 3, 2013.

- Sheridan, Tom (February 27, 2014). "LAKE ELSINORE: Judge halts memorial planned for The Diamond". The Press-Enterprise. Retrieved March 30, 2015.

- American Humanist Association v. City of Lake Elsinore, Case No. 5:13-cv-00989 (C.D. Cal. Feb. 25, 2014).

- Williams, Michael (April 29, 2014). "LAKE ELSINORE: Vets memorial dispute costs city $200,000". The Press-Enterprise. Retrieved March 31, 2015.

- Williams, Michael (June 12, 2014). "LAKE ELSINORE: Veterans memorial plan gets council approval". The Press-Enterprise. Retrieved March 31, 2015.

- Williams, Michael (November 4, 2014). "LAKE ELSINORE: Legal battles over, veterans memorial finally built". The Press-Enterprise. Retrieved March 31, 2015.

- "Preparations Underway, Veterans Memorial to be Unveiled". City of Lake Elsinore. October 8, 2014. Retrieved March 31, 2015.

- Richard Backus (March–April 2007). "Lake Elsinore, Calif., via the Ortega Highway". Motorcycle Classics. Retrieved August 12, 2009.

- "1973 CR250M by Honda - Bike Museum at Bob Logue Motorsports". Archived from the original on October 31, 2010. Retrieved March 18, 2019.

- "LAKE ELSINORE: Skateboard park a hit". July 5, 2015. Retrieved March 13, 2019.

- George, Jacob. "Celebration of Art". Studio 395.

Further reading

- Greene, Edythe J.; Hepler, Elizabeth; Rowden, Mary Louise (2005). Lake Elsinore. Mt. Pleasant, SC: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0738530666.