Ellenroad Mill

Ellenroad Mill was a cotton spinning mill in Newhey, a village in the Milnrow area of Rochdale, England. It was built as a mule spinning mill in 1890 by Stott and Sons and extended in 1899. It was destroyed by fire on 19 January 1916. When it was rebuilt, it was designed and equipped as a ring spinning mill.

The second Ellenroad Mill – the ring mill | |

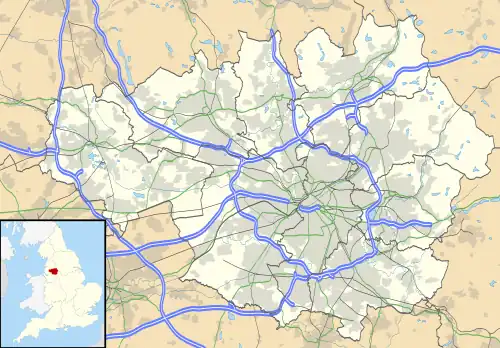

Location in Greater Manchester | |

| Cotton | |

|---|---|

| Alternative names | Ellenroad ring mill |

| Spinning (ring mill) | |

| Location | Newhey, Milnrow, Rochdale, England |

| Coordinates | 53.6011°N 2.1063°W |

| Construction | |

| Built | 1890 |

| Renovated |

|

| Design team | |

| Architect | Stott and Sons |

| Boiler configuration | |

| Boilers | Lancashire, coal fired |

After closure, the mill itself was demolished in 1982, but the engine house – complete with steam engine – and the boiler house chimney were retained. Ownership passed to the Ellenroad Trust. The Ellenroad Ring Mill Engine is steamed on the first Sunday of the month (except January for boiler inspection).

Location

Ellenroad mill was situated on flat land alongside the river in Newhey (archaically "New Hey".[1]) The village lies at the foot of the Pennines, in the valley of the River Beal, 2.7 miles (4.3 km) east-southeast of Rochdale and 10.3 miles (16.6 km) northeast of Manchester.

Historically a part of Lancashire, Newhey was anciently a hamlet within the township of Butterworth. It was described in 1828 as "consisting of several ranges of cottages and two public houses".[2] In the early 19th century, a major road was built through Newhey from Werneth to Littleborough. Newhey was incorporated into the Milnrow Urban District in 1894. There were five mills recorded in Newhey in 1920: including Ellenroad, Newhey, Coral, Haugh and Garfield.

The Rochdale Canal which officially opened in 1804, providing a broad canal link across the Pennines and consequently became an important transport corridor. The canal started at the Bridgewater Canal, linked with the Ashton Canal, and passed through Ancoats, Droylsden, Moston, Middleton and Chadderton before passing to the south of Rochdale and the north of Milnrow and Newhey, towards Todmorden. The canal carried coal and cotton to the mills, and the completed yarn to the weaving sheds. In 1890, the canal company had 2,000 barges and traffic reached 700,000 tons/year, the equivalent of 50 barges a day.[3] It provided an axis for the development of the cotton industry. Newhey was 3 km from the canal and was late in building cotton mills. More significantly the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway built the Oldham Loop Line through Milnrow and Newhey in 1863. The engine house of Ellenroad mill now lies to the south of Junction 21 of the M62 motorway.

Rochdale was a prime site for cotton spinning in 1890. It was conveniently located for the coal fields and the railways made the importation of cotton easy.

| Date | 1883 | 1893 | 1903 | 1913 | 1923 | 1926 | 1933 | 1944 | 1953 | 1962 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rochdale | 1,627 | 1,835 | 2,422 | 3,645 | 3,749 | 3,793 | 3,539 | 2,459 | 1,936 | 983 |

History

The Ellenroad mill was a conventional, late nineteenth century, cotton mill. During the boom of the late 1880s, a limited company, the Ellenroad Spinning Co. Ltd, was formed to build a new mill. They chose the well-respected Oldham architects of Stott and Sons to manage the design and construction. The design was for a conservative five-storey 40-bay mule spinning mill, with detached engine and boiler houses, driving the line shafts by means of a rope drive. Stotts designed 5 mills in Rochdale, for instance in 1888 they had erected the Moss Mill. For the steam engine they went to the local firm of J & W McNaught and chose a single triple-expansion horizontal engine, which in 1890 produced the greatest efficiency in terms of power per ton of coal. The steam was raised by five Lancashire boilers. These required a 220 ft chimney to provide the draught. Work commenced February 1891, and the first cotton was passing through the card room in May 1892, the final mule was installed and in operation by December 1892. Because this was a Stott mill, it is likely that the whole of the machinery would have come from one supplier and this would have been Platt Brothers of Oldham or failing that Dobson & Barlow.[5] The mill would have had humidifiers and a sprinkler system. The mill was extended by Stott and Sons in 1899.

At this point in its history it might be expected that the mill then followed the conventional course of its contemporaries: the industry peaked in 1912 when it produced 8 billion yards of cloth; The First World War of 1914–18 halted the supply of raw cotton; and the British government encouraged its overseas colonies to build mills to spin and weave cotton. The war over, Lancashire would never regain its markets.

However at 2:30 pm on 19 January 1916 the headstock of one of the two mules tended by JW Taylor in Number 2 Spinning Room caught fire. The sprinkler system and the operatives could not contain the fire. The fire brigades of both Rochdale and Oldham were summoned, Oldham were delayed until 4:00. By 5:00 the fire was believed to have been extinguished, but it reignited, and with the help of strong wind burnt fiercely. At 8:00 pm the centre of the mill collapsed. Though it was of fire-proof construction on the patent triple brick arch method, the iron girders had been subjected to great heat and dousing with water, and this caused them to fracture.[6] By the following day the ruins of the mill had become a tourist attraction. The boiler and engine houses were untouched.

The mill was rebuilt, but in a new form: as a ring spinning mill, thus replacing the slower mules with ring frames. Mules still produced the finest spin, but that was a more niche market, and money was now made with rings. More ring spindles could be operated in the same space.[7] Many mills were converted to ring frames, but the most efficient ring frames required a greater floor height, and the positioning of the floor support pillars (and hence the bay size) needed to be changed in order to achieve the greatest spindle density. The new mill was called the Ellenroad Ring Mill to distinguish it from the former Ellenroad mule mill. The opportunity was also taken to reconfigure the engine. The four-cylinder triple-expansion horizontal engine by J & W McNaught was rebuilt as a twin tandem which would deliver the extra power required by the increased number of spindles.

The mill continued to spin cotton into the 1980s. The mill was electrified in 1975, and the engines fell silent but remained intact. After closure in 1982 the mill was largely demolished by 1985 although the boiler house, engine house – complete with steam engine – and the boiler house chimney were retained. These were taken over by the Ellenroad Trust, who have maintained the engine and acquired a beam engine and other smaller engines. The one remaining Lancashire boiler is fired-up once a month to demonstrate these engines in steam.

Architecture

The first mill was designed in 1890 by Stott and Sons. It was a five-storey brick fireproof mule mill, 40 bays by 18. It had corner turrets and 3 projecting towers on south front. The second mill, was a rebuild by other architects.

Power

[8] The J & W McNaught single triple-expansion horizontal engine, with Corliss valves on the HP, was reconfigured in 1916 into a 3000 IHP twin tandem. It has Craig cut off gear attached to Corliss valves on the HP cylinders, and slide valves on the LP cylinders. It is regulated by a Whitehead governor, and drives an 80-ton, 28-foot flywheel grooved for 44 ropes. The engine survives and is steamed regularly.[9]

Equipment

Originally Platt Brothers spinning mules, and breaking and carding equipment. Replaced by ring frames in 1916.

Usage

Cotton spinning

Owners

Ellenroad Spinning Co. Ltd

Ellenroad Steam Museum

The engine house, boiler house and chimney still are complete, with the steam engine, which since 1982, is maintained and steamed once a month by the Ellenroad Trust. It is open to the public every Sunday but in steam first Sunday in the month. On non-steaming days, the engine house is manned by the volunteers, and the public can have a personal tour of the engine.

See also

References

Notes

- Youngs (1991), p. 172.

- Butterworth (1828), p. 113.

- New Moston History Society "Rochdale Canal". Retrieved 16 December 2007.

- Williams & Farnie 1992, p. 46

- Holden 1998, p. 179

- Holden 1998, p. 83

- Hills 1993, p. 212

- Roberts 1921

- Ellenroad Trust, archived from the original on 31 December 2010, retrieved 8 February 2011

Bibliography

- Arnold, Sir Arthur (1864). The history of the cotton famine, from the fall of Sumter to the passing of the Public Works Act (1864). London: Saunders, Otley and Co. Retrieved 14 June 2009.

- Ashmore, Owen (1982). The industrial archaeology of North-west England. Manchester University Press. ISBN 0-7190-0820-4. Retrieved 25 June 2009.

- Chapman, S.J. (1904). The Lancashire Cotton Industry, A Study in Economic Development. Manchester.

- Gurr, Duncan; Hunt, Julian (1998). The Cotton Mills of Oldham. Oldham Education & Leisure. ISBN 0-902809-46-6. Archived from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 7 February 2011.

- Hills, Richard Leslie (1993). Power from Steam: A History of the Stationary Steam Engine. Cambridge University Press. p. 244. ISBN 0-521-45834-X. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- Holden, Roger N. (1998). Stott & Sons : architects of the Lancashire cotton mill. Lancaster: Carnegie. ISBN 1-85936-047-5.

- Marsden, Richard (1884). Cotton Spinning: its development, principles an practice. George Bell and Sons 1903. Retrieved 26 April 2009.

- Nasmith, Joseph (1895). Recent Cotton Mill Construction and Engineering. London: John Heywood. ISBN 1-4021-4558-6. Retrieved 1 March 2009.

- Roberts, A S (1921), "Arthur Robert's Engine List", Arthur Roberts Black Book., One guy from Barlick-Book Transcription, archived from the original on 23 July 2011, retrieved 11 January 2009

- Williams, Mike; Farnie, D.A. (1992). Cotton Mills of Greater Manchester. Carnegie Publishing. ISBN 0-948789-89-1.