Elleanor Eldridge

Elleanor Eldridge (March 1784/1785 – c. 1845) was an African-American/Native American entrepreneur and memoirist from Rhode Island.[1] She is best known for the Memoirs of Elleanor Eldridge (16mo., Providence: B.T. Albro, 1838), which was co-authored with Frances Harriet Whipple Green McDougall.[2] Another edition was published in 1840, and still another in 1842. This volume of 128 pages was published for the purpose of enabling the subject of it to repurchase some property of which she had been perhaps legally, but at all events unfairly, deprived.[1]

Elleanor Eldridge | |

|---|---|

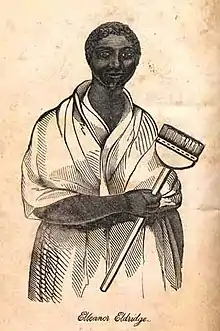

Portrait of Elleanor Eldridge from the frontispiece of the Memoirs of Elleanor Eldridge | |

| Born | March 1784/1785 Warwick, Rhode Island, U.S. |

| Died | c. 1845 |

| Occupation | Entrepreneur, writer |

| Language | English |

| Nationality | American |

| Genre | memoir |

| Notable works | Memoirs of Elleanor Eldridge |

Early years

Elleanor Eldridge was born in Warwick, Rhode Island, March 1784.[3][4][lower-alpha 1]

Her maternal grandmother, Mary Fuller, was a Native American, belonging to the small tribe or clan, called the Fuller family; which was probably a portion of the Narragansett people. Certain it is that this tribe or family once held great possessions in large tracts of land, with a portion of which Mary Fuller purchased her husband Thomas Prophet; who, until his marriage, had been a slave.[5] Her grandfather had been kidnapped at the mouth of the Congo River, on board a ship upon which he had been enticed for the purposes of trade. He was brought to Rhode Island, where he was sold as a slave.[1] Mary Fuller, having witnessed the departing glories of her tribes, died in extreme old age, at the house of her son, Caleb Prophet, being 102 years old. She was buried at the Thomas Greene burying place in Warwick, in the year 1780. Her daughter Hannah married Robin Eldridge, the father of Elleanor.[5]

Career

_-_Original.jpg.webp)

By dint of hard work and prudence, she was enabled to purchase a lot of land on Spring Street, in Providence, upon which she built a house, several times enlarging it until it became, to her, a valuable property, and was nearly paid for. It had cost about US$2,000; on it there was a loan of US$240. On this loan, she paid an annual interest of ten per cent. Having an opportunity to purchase another estate adjoining her own, which materially improved her means of access to her house, she bought it for US$2,000, upon which she paid US$500 cash and gave a mortgage of US$1,500 on her entire estate.[6]

Being taken sick, she rented her property and went away to recover her strength. While gone, the gentleman from whom she borrowed the US$240 died, leaving his estate to his brother. This brother attached Elleanor's property, sold it by the sheriff, and he himself bought it for exactly the amount of the mortgage. Elleanor returned to find herself deprived in a moment of an estate which had cost about US$4,000.[6]

She was not a woman who would submit quietly to such proceedings, and immediately set herself to work to obtain justice. General Ray Greene, Attorney General, assisted her, as did many of the best citizens of Providence, to whom she was well known. To assist in raising money, Memoirs of Elleanor Eldridge was written, and several editions sold. A companion volume, entitled Elleanor's Second Book, was published in 1847. These efforts were successful. Eldridge recovered her property after paying heavily for it, and lived to old age.[7] She died about 1845.[3][4]

Notes

- The African American Registry records Eldridge's date of birth as March 26, 1785.[2]

References

- Hopkins 1880, p. 35.

- "Elleanor Eldridge, businesswoman amid oppression - African American Registry". African American Registry. Retrieved September 26, 2018.

- Appleby, Chang & Goodwin 2015, p. 112.

- "Summary of Memoirs of Elleanor Eldridge". docsouth.unc.edu. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hil. Retrieved September 26, 2018.

- Eldridge 1843, p. 23.

- Hopkins 1880, p. 36.

- Hopkins 1880, p. 37.

Attribution

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Eldridge, Elleanor (1843). Memoirs of Elleanor Eldridge (Public domain ed.). B.T. Albro.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Eldridge, Elleanor (1843). Memoirs of Elleanor Eldridge (Public domain ed.). B.T. Albro. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Hopkins, Stephen (1880). A True Representation of the Plan Formed at Albany: In 1754, for Uniting All the British Northern Colonies, in Order to Their Common Safely and Defence (Public domain ed.). S. S. Rider.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Hopkins, Stephen (1880). A True Representation of the Plan Formed at Albany: In 1754, for Uniting All the British Northern Colonies, in Order to Their Common Safely and Defence (Public domain ed.). S. S. Rider.

Bibliography

- Appleby, Joyce; Chang, Eileen; Goodwin, Neva (17 July 2015). Encyclopedia of Women in American History. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-47162-2.