Elizabeth Clarke

Elizabeth Clarke (c. 1565–1645), alias Bedinfield, was the first woman persecuted by the Witchfinder General, Matthew Hopkins in 1645 in Essex, England. At 80 years old, she was accused of witchcraft by local tailor John Rivet. Hopkins and John Stearne took on the role of investigators, stating that they had seen familiars while watching her. During the process, she was deprived of sleep for multiple nights before confessing and implicating other women in the local area. She was tried at Chelmsford assizes, before being hanged for witchcraft.

Witchcraft trial

Elizabeth Clarke, also known as Bedinfield,[2] was accused of cursing the wife of Manningtree tailor, John Rivet during the winter of 1643.[3] A lynch mob brought her to Sir Harbottle Grimston, her landowner, who decided that she should be tried.[4] Matthew Hopkins, assisted by John Stearne and Mary Phillipps, took up the role of investigator and prosecutor, known as "Watcher".[5]

Although torture was illegal in England, suspected witches were subject to scrutiny by their Watchers. In Clarke's case, Hopkins and colleagues including John Stearne watched her for several days and nights without allowing her to sleep. After this treatment, Hopkins claimed to have witnessed Clarke summoning familiars, imps in animal form.[6] During this ordeal, Clarke implicated other women from Manningtree, Anne West and her daughter Rebecca, Anne Leech, Helen Clarke, and Elizabeth Gooding as well as women from other villages. Clarke stated that she had been brought into witchcraft by Anne West, who took pity on her due to her poverty and only having one leg.[2] The women discovered by Hopkins were tried at Chelmsford assizes on 17 July 1645.[1] Elizabeth then confessed due to the persuading, forcing and imprisonment, this led to 35 women who were accused and put to prison.

List of Clarke's familiars

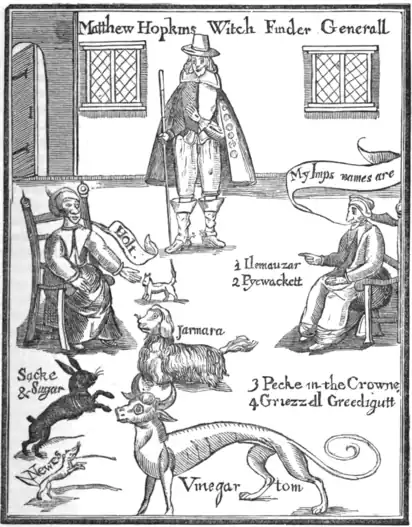

During the testimonies of the watchers, they described many of the imps that he saw with Clarke, including:

- Jarmana - a white dog with sandy spots, fat with short legs[2]

- Vinegar Tom - a greyhound with long legs,[2] who turned into a 4-year-old boy with no head[7]

- A black imp[2]

- Newes - A pole cat with a large head[2][8]

- Hoult - a white imp, smaller than a cat [8]

- White imps that went to bed with Clarke in the shape of a "proper gentleman" with a laced band.[2]

- Three brown imps from her mother[9]

- Sacke and Sugar - a demonic black rabbit[4][8]

- Other familiars referred to by name but not description: Elemauzer, Pyewacket, Peck-in-the-crown & Grizel Greedigut.[7]

References

- Hopkins, Matthew; Stearne, John (2007). "Appendix 2 (Page 52)". In Davies, S. F. (ed.). The discovery of witches and witchcraft : the writings of the witchfinders. Puckrel Publishing. ISBN 9780955635014. Retrieved 1 March 2020.

- Kekewich, Margaret Lucille, ed. (1994). Princes and peoples : France and British Isles, 1620-1714 : an anthology of primary sources. Manchester University Press in association with the Open University. p. 132. ISBN 9780719045738. Retrieved 1 March 2020.

- Sheldon, Natasha (December 2018). "The Macabre Career of Witch Finder General Belonged to this Scheming Man in the 17th Century". History Collection. Retrieved 1 March 2020.

- "Matthew Hopkins Biography – Witchfinder General". Biographics. 30 May 2019. Retrieved 1 March 2020.

- Smyth, Frank (1973). Modern Witchcraft. Harper Collins Publishers. p. 67. ISBN 9780060870386. Retrieved 1 March 2020.

- Hartley, Cathy (2013). A Historical Dictionary of British Women. Routledge. p. 104. ISBN 9781135355333.

- Dickens, Charles (1857). Household Words: Volume 16. Bradley and Evans. p. 140. Retrieved 1 March 2020.

- Jones, Tracy (30 October 2015). "Devil marks, drownings and death: The story of the Witchfinder General in Essex". Culture 24. Retrieved 1 March 2020.

- Howell, Thomas Bayly, ed. (1816). A Complete Collection of State Trials and Proceedings for High Treason and Other Crimes and Misdemeanors from the Earliest Period to the Year 1783, with Notes and Other Illustrations: Volume 4. Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme and Brown. pp. 532–540. Retrieved 1 March 2020.

Further reading

- The Witch-Cult in Western Europe

- Howell, Thomas Bayly, ed. (1816). A Complete Collection of State Trials and Proceedings for High Treason and Other Crimes and Misdemeanors from the Earliest Period to the Year 1783, with Notes and Other Illustrations: Volume 4. Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme and Brown. pp. 532–540. Retrieved 1 March 2020.