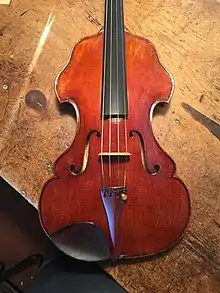

Viola

The viola (/viˈoʊlə/ vee-OH-lə,[1] Italian: [ˈvjɔːla, viˈɔːla]) is a string instrument that is bowed, plucked, or played with varying techniques. Slightly larger than a violin, it has a lower and deeper sound. Since the 18th century, it has been the middle or alto voice of the violin family, between the violin (which is tuned a perfect fifth higher) and the cello (which is tuned an octave lower).[2] The strings from low to high are typically tuned to C3, G3, D4, and A4.

| |

| String instrument | |

|---|---|

| Other names | French: alto; German: Bratsche |

| Hornbostel–Sachs classification | 321.322-71 (Composite chordophone sounded by a bow) |

| Playing range | |

| |

| Related instruments | |

| Sound sample | |

In the past, the viola varied in size and style, as did its names. The word viola originates from the Italian language. The Italians often used the term viola da braccio, meaning, literally, 'of the arm'. "Brazzo" was another Italian word for the viola, which the Germans adopted as Bratsche. The French had their own names: cinquiesme was a small viola, haute contre was a large viola, and taile was a tenor. Today, the French use the term alto, a reference to its range.

The viola was popular in the heyday of five-part harmony, up until the eighteenth century, taking three lines of the harmony and occasionally playing the melody line. Music for the viola differs from most other instruments in that it primarily uses the alto clef. When viola music has substantial sections in a higher register, it switches to the treble clef to make it easier to read.

The viola often plays the "inner voices" in string quartets and symphonic writing, and it is more likely than the first violin to play accompaniment parts. The viola occasionally plays a major, soloistic role in orchestral music. Examples include the symphonic poem Don Quixote, by Richard Strauss, and the symphony/concerto Harold en Italie, by Hector Berlioz. In the earlier part of the 20th century, more composers began to write for the viola, encouraged by the emergence of specialized soloists such as Lionel Tertis and William Primrose. English composers Arthur Bliss, York Bowen, Benjamin Dale, Frank Bridge, Benjamin Britten, Rebecca Clarke and Ralph Vaughan Williams all wrote substantial chamber and concert works. Many of these pieces were commissioned by, or written for, Lionel Tertis. William Walton, Bohuslav Martinů, Tōru Takemitsu, Tibor Serly, Alfred Schnittke, and Béla Bartók have written well-known viola concertos. The concerti by Béla Bartók, Paul Hindemith, Carl Stamitz, Georg Philipp Telemann, and William Walton are considered major works of the viola repertoire. Paul Hindemith, who was a violist, wrote a substantial amount of music for viola, including the concerto Der Schwanendreher.

Form

The viola is similar in material and construction to the violin. A full-size viola's body is between 25 mm (1 in) and 100 mm (4 in) longer than the body of a full-size violin (i.e., between 38 and 46 cm [15–18 in]), with an average length of 41 cm (16 in). Small violas typically made for children typically start at 30 cm (12 in), which is equivalent to a half-size violin. For a child who needs a smaller size, a fractional-sized violin is often strung with the strings of a viola.[3] Unlike the violin, the viola does not have a standard full size. The body of a viola would need to measure about 51 cm (20 in) long to match the acoustics of a violin, making it impractical to play in the same manner as the violin.[4] For centuries, viola makers have experimented with the size and shape of the viola, often adjusting proportions or shape to make a lighter instrument with shorter string lengths, but with a large enough sound box to retain the viola sound. Prior to the eighteenth century, violas had no uniform size. Large violas (tenors) were designed to play the lower register viola lines or second viola in five part harmony depending on instrumentation. A smaller viola, nearer the size of the violin, was called a vertical viola or an alto viola. It was more suited to higher register writing, as in the viola 1 parts, as their sound was usually richer in the upper register. Its size was not as conducive to a full tone in the lower register.

Several experiments have intended to increase the size of the viola to improve its sound. Hermann Ritter's viola alta, which measured about 48 cm (19 in), was intended for use in Wagner's operas.[5] The Tertis model viola, which has wider bouts and deeper ribs to promote a better tone, is another slightly "nonstandard" shape that allows the player to use a larger instrument. Many experiments with the acoustics of a viola, particularly increasing the size of the body, have resulted in a much deeper tone, making it resemble the tone of a cello. Since many composers wrote for a traditional-sized viola, particularly in orchestral music, changes in the tone of a viola can have unintended consequences upon the balance in ensembles.

One of the most notable makers of violas of the twentieth century was Englishman A. E. Smith, whose violas are sought after and highly valued. Many of his violas remain in Australia, his country of residence, where during some decades the violists of the Sydney Symphony Orchestra had a dozen of them in their section.

More recent (and more radically shaped) innovations have addressed the ergonomic problems associated with playing the viola by making it shorter and lighter, while finding ways to keep the traditional sound. These include the Otto Erdesz "cutaway" viola, which has one shoulder cut out to make shifting easier;[6] the "Oak Leaf" viola, which has two extra bouts; viol-shaped violas such as Joseph Curtin's "Evia" model, which also uses a moveable neck and maple-veneered carbon fibre back, to reduce weight:[7] violas played in the same manner as cellos (see vertical viola); and the eye-catching "Dalí-esque" shapes of both Bernard Sabatier's violas in fractional sizes—which appear to have melted—and David Rivinus' Pellegrina model violas.[8]

Other experiments that deal with the "ergonomics vs. sound" problem have appeared. The American composer Harry Partch fitted a viola with a cello neck to allow the use of his 43-tone scale, called the "adapted viola". Luthiers have also created five-stringed violas,[9] which allow a greater playing range.

Method of playing

A person who plays the viola is called a violist or a viola player. The technique required for playing a viola has certain differences compared with that of a violin, partly because of its larger size: the notes are spread out farther along the fingerboard and often require different fingerings. The viola's less responsive strings and the heavier bow warrant a somewhat different bowing technique, and a violist has to lean more intensely on the strings.[10]

- The viola is held in the same manner as the violin; however, due to its larger size, some adjustments must be made to accommodate. The viola, just like the violin, is placed on top of the left shoulder between the shoulder and the left side of the face (chin). Because of the viola's size, violists with short arms tend to use smaller-sized instruments for easier playing. The most immediately noticeable adjustments that a player accustomed to playing the violin has to make are to use wider-spaced fingerings. It is common for some players to use a wider and more intense vibrato in the left hand, facilitated by employing the fleshier pad of the finger rather than the tip, and to hold the bow and right arm farther away from the player's body. A violist must bring the left elbow farther forward or around, so as to reach the lowest string, which allows the fingers to press firmly and so create a clearer tone. Different positions are often used, including half position.

- The viola is strung with thicker gauge strings than the violin.[11] This, combined with its larger size and lower pitch range, results in a deeper and mellower tone. However, the thicker strings also mean that the viola responds to changes in bowing more slowly. Practically speaking, if a violist and violinist are playing together, the violist must begin moving the bow a fraction of a second sooner than the violinist. The thicker strings also mean that more weight must be applied with the bow to make them vibrate.

- The viola's bow has a wider band of horsehair than a violin's bow, which is particularly noticeable near the frog (or heel in the UK). Viola bows, at 70–74 g (2.5–2.6 oz), are heavier than violin bows (58–61 g [2.0–2.2 oz]). The profile of the rectangular outside corner of a viola bow frog generally is more rounded than on violin bows.

Tuning

The viola's four strings are normally tuned in fifths: the lowest string is C (an octave below middle C), with G, D, and A above it. This tuning is exactly one fifth below the violin,[12] so that they have three strings in common—G, D, and A—and is one octave above the cello.

Each string of a viola is wrapped around a peg near the scroll and is tuned by turning the peg. Tightening the string raises the pitch; loosening the string lowers the pitch. The A string is normally tuned first, to the pitch of the ensemble: generally 400–442 Hz. The other strings are then tuned to it in intervals of fifths, usually by bowing two strings simultaneously. Most violas also have adjusters—fine tuners, particularly on the A string that make finer changes. These adjust the tension of the string via rotating a small knob above the tailpiece. Such tuning is generally easier to learn than using the pegs, and adjusters are usually recommended for younger players and put on smaller violas, though pegs and adjusters are usually used together. Some violists reverse the stringing of the C and G pegs, so that the thicker C string does not turn so severe an angle over the nut, although this is uncommon.

Small, temporary tuning adjustments can also be made by stretching a string with the hand. A string may be tuned down by pulling it above the fingerboard, or tuned up by pressing the part of the string in the pegbox. These techniques may be useful in performance, reducing the ill effects of an out-of-tune string until an opportunity to tune properly.

The tuning C–G–D–A is used for the great majority of all viola music.[13] However, other tunings are occasionally employed, both in classical music, where the technique is known as scordatura, and in some folk styles. Mozart, in his Sinfonia Concertante for Violin, Viola and Orchestra in E♭, wrote the viola part in D major, and specified that the violist raises the strings in pitch by a semitone. He probably intended to give the viola a brighter tone so the rest of the ensemble would not overpower it. Lionel Tertis, in his transcription of the Elgar cello concerto, wrote the slow movement with the C string tuned down to B♭, enabling the viola to play one passage an octave lower.

Organizations and research

A renewal of interest in the viola by performers and composers in the twentieth century led to increased research devoted to the instrument. Paul Hindemith and Vadim Borisovsky made an early attempt at an organization, in 1927, with the Violists' World Union. But it was not until 1968, with the creation of the Viola-Forschungsgesellschaft, now the International Viola Society (IVS), that a lasting organization took hold. The IVS now consists of twelve chapters around the world, the largest being the American Viola Society (AVS), which publishes the Journal of the American Viola Society. In addition to the journal, the AVS sponsors the David Dalton Research Competition and the Primrose International Viola Competition.

The 1960s also saw the beginning of several research publications devoted to the viola, beginning with Franz Zeyringer's, Literatur für Viola, which has undergone several versions, the most recent being in 1985. In 1980, Maurice Riley produced the first attempt at a comprehensive history of the viola, in his History of the Viola, which was followed with the second volume in 1991. The IVS published the multi-language Viola Yearbook from 1979 to 1994, during which several other national chapters of the IVS published respective newsletters. The Primrose International Viola Archive at Brigham Young University houses the greatest amount of material related to the viola, including scores, recordings, instruments, and archival materials from some of the world's greatest violists.[14]

Music

Reading music

Music that is written for the viola primarily uses the alto clef, which is otherwise rarely used. Viola music employs the treble clef when there are substantial sections of music written in a higher register. The alto clef is defined by the placement of C4 on the middle line of the staff. In treble clef, this note is placed one ledger line below the staff and in the bass clef (used, notably, by the cello and double bass) it is placed one ledger line above.[15]

As the viola is tuned exactly one octave above the cello (meaning that the viola retains the same string notes as the cello, but an octave higher), music that is notated for the cello can be easily transcribed for alto clef without any changes in key. For example, there are numerous editions of Bach's Cello Suites transcribed for viola.[16] The viola also has the advantage of smaller scale-length, which means that the stretches on the cello are easier on the viola. However, due the cello's larger range, ease of playing in higher positions, and abilities to play chords, some works transcribed for viola do require additional modification for ease of playing on the instrument.

Role in pre-twentieth century works

In early orchestral music, the viola part was usually limited to filling in harmonies, with very little melodic material assigned to it. When the viola was given a melodic part, it was often duplicated (or was in unison with) the melody played by other strings.[17]

The concerti grossi, Brandenburg Concertos, composed by J. S. Bach, were unusual in their use of viola. The third concerto grosso, scored for three violins, three violas, three cellos, and basso continuo, requires virtuosity from the violists. Indeed, Viola I has a solo in the last movement which is commonly found in orchestral auditions.[18] The sixth concerto grosso, Brandenburg Concerto No. 6, which was scored for 2 violas "concertino", cello, 2 violas da gamba, and continuo, had the two violas playing the primary melodic role.[19] He also used this unusual ensemble in his cantata, Gleichwie der Regen und Schnee vom Himmel fällt, BWV 18 and in Mein Herze schwimmt im Blut, BWV 199, the chorale is accompanied by an obbligato viola.

There are a few Baroque and Classical concerti, such as those by Georg Philipp Telemann (one for solo viola, being one of the earliest viola concertos known, and one for two violas), Alessandro Rolla, Franz Anton Hoffmeister and Carl Stamitz.

The viola plays an important role in chamber music. Mozart used the viola in more creative ways when he wrote his six string quintets. The viola quintets use two violas, which frees them (especially the first viola) for solo passages and increases the variety of writing that is possible for the ensemble. Mozart also wrote for the viola in his Sinfonia Concertante, a set of two duets for violin and viola, and the Kegelstatt Trio for viola, clarinet, and piano. The young Felix Mendelssohn wrote a little-known Viola Sonata in C minor (without opus number, but dating from 1824). Robert Schumann wrote his Märchenbilder for viola and piano. He also wrote a set of four pieces for clarinet, viola, and piano, Märchenerzählungen.

Max Bruch wrote a romance for viola and orchestra, his Op. 85, which explores the emotive capabilities of the viola's timbre. In addition, his Eight pieces for clarinet, viola, and piano, Op. 83, features the viola in a very prominent, solo aspect throughout. His Concerto for Clarinet, Viola, and Orchestra, Op. 88 has been quite prominent in the repertoire and has been recorded by prominent violists throughout the 20th century.]

From his earliest works, Brahms wrote music that prominently featured the viola. Among his first published pieces of chamber music, the sextets for strings Op. 18 and Op. 36 contain what amounts to solo parts for both violas. Late in life, he wrote two greatly admired sonatas for clarinet and piano, his Op. 120 (1894): he later transcribed these works for the viola (the solo part in his Horn Trio is also available in a transcription for viola). Brahms also wrote "Two Songs for Alto with Viola and Piano", Op. 91, "Gestillte Sehnsucht" ("Satisfied Longing") and "Geistliches Wiegenlied" ("Spiritual Lullaby") as presents for the famous violinist Joseph Joachim and his wife, Amalie. Dvořák played the viola and apparently said that it was his favorite instrument: his chamber music is rich in important parts for the viola. Two Czech composers, Bedřich Smetana and Leoš Janáček, included significant viola parts, originally written for viola d'amore, in their quartets "From My Life" and "Intimate Letters" respectively: the quartets begin with an impassioned statement by the viola. This is similar to Bach, Mozart, and Beethoven all occasionally played the viola part in chamber music.

The viola occasionally has a major role in orchestral music, a prominent example being Richard Strauss' tone poem Don Quixote for solo cello and viola and orchestra. Other examples are the "Ysobel" variation of Edward Elgar's Enigma Variations and the solo in his other work, In the South (Alassio), the pas de deux scene from Act 2 of Adolphe Adam's Giselle and the "La Paix" movement of Léo Delibes's ballet Coppélia, which features a lengthy viola solo.

Gabriel Fauré's Requiem was originally scored (in 1888) with divided viola sections, lacking the usual violin sections, having only a solo violin for the Sanctus. It was later scored for orchestra with violin sections, and published in 1901. Recordings of the older scoring with violas are available.[20]

While the viola repertoire is quite large, the amount written by well-known pre-20th-century composers is relatively small. There are many transcriptions of works for other instruments for the viola and the large number of 20th-century compositions is very diverse. See "The Viola Project" at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music, where Professor of Viola Jodi Levitz has paired a composer with each of her students, resulting in a recital of brand-new works played for the very first time.

Twentieth century and beyond

In the earlier part of the 20th century, more composers began to write for the viola, encouraged by the emergence of specialized soloists such as Lionel Tertis. Englishmen Arthur Bliss, York Bowen, Benjamin Dale, and Ralph Vaughan Williams all wrote chamber and concert works for Tertis. William Walton, Bohuslav Martinů, and Béla Bartók wrote well-known viola concertos. Paul Hindemith wrote a substantial amount of music for the viola; being himself a violist, he often performed his own works. Claude Debussy's Sonata for flute, viola and harp has inspired a significant number of other composers to write for this combination.

Charles Wuorinen composed his virtuosic Viola Variations in 2008 for Lois Martin. Elliott Carter also wrote several works for viola including his Elegy (1943) for viola and piano; it was subsequently transcribed for clarinet. Ernest Bloch, a Swiss-born American composer best known for his compositions inspired by Jewish music, wrote two famous works for viola, the Suite 1919 and the Suite Hébraïque for solo viola and orchestra. Rebecca Clarke was a 20th-century composer and violist who also wrote extensively for the viola. Lionel Tertis records that Edward Elgar (whose cello concerto Tertis transcribed for viola, with the slow movement in scordatura), Alexander Glazunov (who wrote an Elegy, Op. 44, for viola and piano), and Maurice Ravel all promised concertos for viola, yet all three died before doing any substantial work on them.

In the latter part of the 20th century a substantial repertoire was produced for the viola; many composers including Miklós Rózsa, Revol Bunin, Alfred Schnittke, Sofia Gubaidulina, Giya Kancheli and Krzysztof Penderecki, have written viola concertos. The American composer Morton Feldman wrote a series of works entitled The Viola in My Life, which feature concertante viola parts. In spectral music, the viola has been sought after because of its lower overtone partials that are more easily heard than on the violin. Spectral composers like Gérard Grisey, Tristan Murail, and Horațiu Rădulescu have written solo works for viola. Neo-Romantic, post-Modern composers have also written significant works for viola including Robin Holloway Viola Concerto op.56 and Sonata op.87, Peter Seabourne a large five-movement work with piano, Pietà, Airat Ichmouratov Concerto for Viola N1 Op.7[21] and Three Romances for Viola, Strings and Harp Op.22.[22]

Contemporary pop music

The viola is sometimes used in contemporary popular music, mostly in the avant-garde. John Cale of The Velvet Underground used the viola,[23] as do some modern groups such as alternative rock band 10,000 Maniacs, Imagine Dragons,[24] folk duo John & Mary,[25] British Sea Power,[26] The Airborne Toxic Event, Marillion, and others often with instruments in a chamber setting. Jazz music has also seen its share of violists, from those used in string sections in the early 1900s to a handful of quartets and soloists emerging from the 1960s onward. It is quite unusual though, to use individual bowed string instruments in contemporary popular music.

In folk music

Although not as commonly used as the violin in folk music, the viola is nevertheless used by many folk musicians across the world. Extensive research into the historical and current use of the viola in folk music has been carried out by Dr. Lindsay Aitkenhead. Players in this genre include Eliza Carthy, Mary Ramsey, Helen Bell, and Nancy Kerr. Clarence "Gatemouth" Brown was the viola's most prominent exponent in the genre of blues.

The viola is also an important accompaniment instrument in Slovakian, Hungarian and Romanian folk string band music, especially in Transylvania. Here the instrument has three strings tuned G3–D4–A3 (note that the A is an octave lower than found on the standard instrument), and the bridge is flattened with the instrument playing chords in a strongly rhythmic manner. In this usage, it is called a kontra or brácsa (pronounced "bra-cha", from German Bratsche, "viola").

Performers

There are few well-known viola virtuoso soloists, perhaps because little virtuoso viola music was written before the twentieth century. Pre-twentieth century viola players of note include Carl Stamitz, Alessandro Rolla, Antonio Rolla, Chrétien Urhan, Casimir Ney, Louis van Waefelghem, and Hermann Ritter. Important viola pioneers from the twentieth century were Lionel Tertis, William Primrose, composer/performer Paul Hindemith, Théophile Laforge, Cecil Aronowitz, Maurice Vieux, Vadim Borisovsky, Lillian Fuchs, Dino Asciolla, Frederick Riddle, Walter Trampler, Ernst Wallfisch, Csaba Erdélyi, the only violist to ever win the Carl Flesch International Violin Competition, and Emanuel Vardi, the first violist to record the 24 Caprices by Paganini on viola. Many noted violinists have publicly performed and recorded on the viola as well, among them Eugène Ysaÿe, Yehudi Menuhin, David Oistrakh, Pinchas Zukerman, Maxim Vengerov, Julian Rachlin, James Ehnes, and Nigel Kennedy.

Among the great composers, several preferred the viola to the violin when they were playing in ensembles,[27] the most noted being Ludwig van Beethoven, Johann Sebastian Bach[28] and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. Other composers also chose to play the viola in ensembles, including Joseph Haydn, Franz Schubert, Felix Mendelssohn, Antonín Dvořák, and Benjamin Britten. Among those noted both as violists and as composers are Rebecca Clarke and Paul Hindemith. Contemporary composers and violists Kenji Bunch, Scott Slapin, and Lev Zhurbin have written a number of works for viola.

Electric violas

Amplification of a viola with a pickup, an instrument amplifier (and speaker), and adjusting the tone with a graphic equalizer can make up for the comparatively weaker output of a violin-family instrument string tuned to notes below G3. There are two types of instruments used for electric viola: regular acoustic violas fitted with a piezoelectric pickup and specialized electric violas, which have little or no body.[29] While traditional acoustic violas are typically only available in historically used earth tones (e.g., brown, reddish-brown, blonde), electric violas may be traditional colors or they may use bright colors, such as red, blue or green. Some electric violas are made of materials other than wood.

Most electric instruments with lower strings are violin-sized, as they use the amp and speaker to create a big sound, so they do not need a large soundbox. Indeed, some electric violas have little or no soundbox, and thus rely entirely on amplification. Fewer electric violas are available than electric violins. It can be hard for violists who prefer a physical size or familiar touch references of a viola-sized instrument, when they must use an electric viola that uses a smaller violin-sized body. Welsh musician John Cale, formerly of The Velvet Underground, is one of the more notable users of such an electric viola and he has used them both for melodies in his solo work and for drones in his work with The Velvet Underground (e.g. "Venus in Furs"). Other notable players of the electric viola are Geoffrey Richardson of Caravan[30] and Mary Ramsey of 10,000 Maniacs.[31]

Instruments may be built with an internal preamplifier, or may put out an unbuffered transducer signal. While such signals may be fed directly to an amplifier or mixing board, they often benefit from an external preamp/equalizer on the end of a short cable, before being fed to the sound system. In rock and other loud styles, the electric viola player may use effects units such as reverb or overdrive.

See also

Notes

References

- "viola". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary.

- Until the end of the 17th century, there was the tenor violin, tuned a perfect fourth below the viola.

- "Violin and Viola". Oakville Suzuki Association. 2009. Archived from the original on 2013-09-27. Retrieved 2013-07-13.

- "The Violin Octet". The New Violin Family Association. 2004–2009. Retrieved 2011-05-18.

- Maurice, Joseph. "Michael Balling: Pioneer German Solo Violist with a New Zealand Interlude". American Viola Society (Summer 2003). Archived from the original on 2006-08-23. Retrieved 2006-07-31.

- Curtin, Joseph. "Otto Erdesz Remembered". The Strad (November 2000). Archived from the original on 2006-10-17. Retrieved 2006-07-30.

- Curtin, Joseph (Winter 1999). "Project Evia". American Lutherie Journal (60). Archived from the original on 2006-12-28. Retrieved 2006-10-08.

- "The Pellegrina – David L. Rivinus Violin Maker". Rivinus-instruments.com. Archived from the original on 2013-05-15. Retrieved 2013-04-29.

- "Five String Violas: What is special about a 5-string viola?". Retrieved 2023-09-11.

- Constance Meyer (12 December 2004). "Violas: They're hardly second string". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 7 March 2021.

- Jackson, Ronald John (2005). Performance Practice: A Dictionary-guide for Musicians. Psychology Press. ISBN 9780415941396. Retrieved 28 April 2019.

- "5 Differences Between Violas and Violins". consordini.com. 13 March 2017. Retrieved 28 April 2019.

- "Viola Online - Tuning".

- "Growth in the Primrose Archives". Strad. Vol. 110, no. 1306. 1999.

- Piston, Walter: Orchestration, W. W. Norton, New York: 1955. ISBN 0393097404

- "Category:For viola (arr) - IMSLP: Free Sheet Music PDF Download". imslp.org. Retrieved 2023-01-12.

- Howard, Jacinta K. (August 1966). "The Viola—Up from Obscurity". American String Teacher. 16 (3): 12–16. doi:10.1177/000313136601600308. ISSN 0003-1313. S2CID 186782038.

- New Zealand Symphony Orchestra (July 2020). "NZSO-2020-July-Associate-Principal-Viola-Excerpts.pdf" (PDF).

- Berlioz, Hector; A Treatise on Modern Orchestration and Instrumentation; J. Alfred Novello; Paris: 1856.

- Gilman, Lawrence (1951). Orchestral Music: An Armchair Guide. Oxford University Press.

- "Ichmouratov: Viola Concerto No.1/Piano Concerto". www.chandos.net. Retrieved 29 September 2023.

- "Ichmouratov: Orchestral Works". www.chandos.net. Retrieved 29 September 2023.

- Grow, Kory (2017-03-10). "John Cale Reflects on 50th Anniversary of 'Velvet Underground and Nico'". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 2021-08-06.

- "Imagine Dragons is a study in contradictions". The Georgia Straight. 2012-10-03. Retrieved 2021-08-06.

- "Meet The Father-Daughter Duo In The Boston Symphony Orchestra". www.wbur.org. Retrieved 2021-08-06.

- Rogers, Holly (2014-11-20). Music and Sound in Documentary Film. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-91604-8.

- "Groves Dictionary". Archived from the original on 2012-12-15. Retrieved 2009-02-26.

- Forkel, Johann Nikolaus. Über Johann Sebastian Bachs Leben, Kunst und Kunstwerke. Herausgegeben und eingeleitet von Claudia Maria Knispel (in German). Berlin: Henschel Verlag.

- "Electric Viola: Amplifying Violas in Modern Music". Johnson String Instrument. Retrieved 6 August 2021.

- Barnes, Mike (2016-04-01). "Caravan's Geoffrey Richardson on sobriety and going solo". Louder. Retrieved 2021-08-06.

- Iwasaki, Scott (8 January 2020). "Mary Ramsey celebrates 25 years as a 10,000 Maniac". ParkRecord.com. Retrieved 2021-08-06.

Further reading

- Dalton, David. "The Viola & Violists." Primrose International Viola Archive. Retrieved October 8, 2006

- Chapman, Eric. "Joseph Curtin and the Evia". Journal of the American Viola Society, vol. 20, no. 1, Spring 2004, pp. 41–42.

- Tertis, Lionel. My Viola and I. Kahn & Averill, London (1991)

External links

- American Viola Society website

- Primrose International Viola Archive library website

- International Viola Society website

- Rivinus- David Rivinus' site with pictures of his oddly shaped violas

- "Evia" 1999 prototype, Joseph Curtin's experimental viola model

- Oliver Viola

- History of the Viola

- Milward Violas – David Milward's site. Contemporary viola design and build, information and articles

- Viola in music – The role of viola in music. Information, description of works, videos, free sheet music, MIDI files, RSS update

- Anechoic Recordings of Viola Tones – University of Iowa Electronic Music Studios

- Dr. Lindsay Aitkenhead's folk viola research page Archived 2009-07-19 at the Wayback Machine

- Nigel Keay's Contemporary Viola, scores and articles of recent repertoire for the viola.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. Very brief, but it does have names for the viola in French, German and Italian.