Elberfeld system

The Elberfeld system was a system for aiding the poor in 19th-century Germany. It was a success when it was inaugurated in Elberfeld in 1853 and was adopted by many other German cities, but by the turn of the century an increasing population became more than the Elberfeld system (which relied on volunteer social workers) could handle, and it fell out of use.[1]

Background

The first attempts to create a reformed poor relief system in Elberfeld began in 1800, when, dissatisfied with existing conditions, the city appointed six visitors to investigate applications for relief. The visitors were increased to 12 the following year. In 1802 there was a great increase. The city was divided into eight districts and these districts into four sections, and a board of supervisors chosen.

At the time (the first half of the 19th century), the textile-manufacturing cities of Barmen and Elberfeld were pioneering the industrialization of Germany.[2] Immigration swelled the population of Elberfeld from 16,000 to 19,000 in 1810 to 31,000 to 40,000 in 1840, and the two cities were among the most densely populated municipalities in Germany. [2]

The 1802 system was further extended in 1841. In 1850, dissatisfaction having arisen in several quarters, the Lutheran church attempted to do the work. Matters were not improved. The population of poor people was disproportionately high. And the centrally managed system of urban poor relief that the two cities had inherited proved to be too expensive and inefficient to cope with the new scale of the problem. [2]

The Elberfeld system was a new structure of care that attempted to adapt to the new conditions.[3][2]

The system

In 1852, a plan proposed by a banker, Daniel von Heydt, was put in operation.[3][2] The administration of poor relief was decentralized. [3][2][1] Working under a citywide poor office, subdepartments were established in smaller precincts - their relief workers worked on behalf of the central office.[3][1] There were 252 precincts, each to care for four to 10 families.[2]

Each precinct was in the care of an unsalaried[3][1] almoner whose duty was to investigate each applicant for aid and to make visits every two weeks as long as aid was given. (Although, aid was not always extended - initial assistance was limited to two weeks and further services had to be approved again.[2][1]) Fourteen precincts formed a district. The almoners met every two weeks under direction of an unpaid overseer to discuss the cases and to vote on needed relief. Those proceedings were reported to the directors, being the mayor as ex officio chairman, four councilmen, and four citizens (also unpaid), who met the day following to review and supervise the work throughout the city. In emergency cases the almoner might furnish assistance.

Relief was granted in money according to a fixed schedule for two weeks at a time, any earning the family may have garnered being deducted. Tools were furnished when advisable. The funds distributed to the poor came either from city coffers or from existing charitable foundations.[1]

Key to the system was that the almoners and overseers served voluntarily.[3][1] They came mostly from the middle class, being minor officials, craftsmen or merchants.[1] Women were also accepted as almoners, giving them a rare (for the time) opportunity to participate in public life.[1] The larger number of volunteers decreased both the number of clients per almoner, and the total system costs. [2][1]

The system gave great satisfaction; the expenses in proportion to the population gradually decreased, and the condition of the poor is said to have improved. The essential principles of the Elberfeld system found application in the public-relief administration of the cities of the Rhineland,[1] notably in Cologne, Crefeld, Düsseldorf, Aix-la-Chapelle, and Remscheid. A similar system had been employed in Hamburg.[2] The Elberfeld system influenced the reorganization of relief systems in most of the German cities. Attempts to introduce the system in non-German cities were unsuccessful.

In the last third of the 19th century, however, immigration fuelled by industrialization once again increased the numbers of the needy, and the poor relief volunteers reached the limits of their capabilities. [1] In the larger cities particularly, there was a return to greater centralization and professionalisation of poor relief.[2][1]

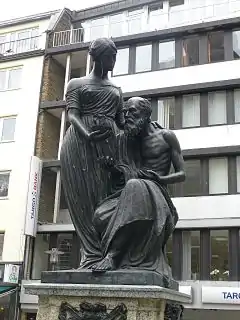

In 1903, sculptor Wilhelm Neumann-Torborg (who was born in Elberfeld) created a bronze sculpture, The "Elberfeld Poor Relief Monument," to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the founding of the Elberfeld system.[4] The statue was mostly destroyed during the Second World War, when the bronze figures were melted down for metal.[5][4] But in 2003, the granite pedestal of the monument was rediscovered during excavations at the Elberfeld Old Reformed Church, and placed on display in Blankstrasse, Wuppertal.[5] In 2011, it was restored thanks to 24 private donations.[4] The bronze figures were recast at the Kayser Art Foundry by sculptor Shwan Kamal in Düsseldorf.[4]

References

- Wolfgang R. Krabbe (1989). "Die deutsche Stadt im 19. und 20.Jahrhundert". Göttingen. p. 101. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- Gunther Beninde. "Hamburger Modell und Elberfelder System". Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- Christoph Sachße (22 May 2002). "Traditionslinien bürgerschaftlichen Engagements in Deutschland". Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung. Retrieved 4 December 2015.

- Florian Launus (29 May 2011). "Ein neues Denkmal für Elberfeld: Bronzefrau speist Hungernden". Westdeutsche Zeiting. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- Cécile Zachlod. "Das Armenpflegedenkmal von Elberfeld im Wandel der Denkmalkultur um 1900" (PDF). Bergischer Geschichtsverein, Abt. Wuppertal. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 July 2017. Retrieved 30 November 2015.

Bibliography

- Gerhard Deimling: 150 Jahre Elberfelder System. Ein Nachruf, in: Geschichte im Wuppertal 12 (2003), pp. 46-57

- Barbara Lube: Mythos und Wirklichkeit des Elberfelder Systems, in: Karl-Hermann Beeck (editor), Gründerzeit. Versuch einer Grenzbestimmung im Wuppertal (= Schriften des Vereins für Rheinische Kirchengeschichte, Volume 80), Köln/Bonn 1984, pp. 158-184

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Gilman, D. C.; Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)